Phil Donahue

Phil Donahue | |

|---|---|

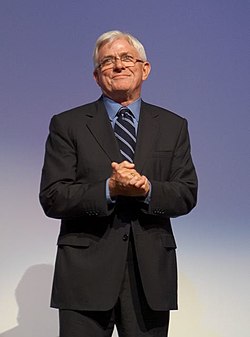

Donahue in 2007 | |

| Born | Phillip John Donahue December 21, 1935 Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | August 18, 2024 (aged 88) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | University of Notre Dame (BBA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1957–2024 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5 |

Phillip John Donahue (December 21, 1935 – August 18, 2024) was an American media personality, writer, film producer, and the creator and host of The Phil Donahue Show. The television program, later known simply as Donahue, was the first popular talk show to feature a format that included audience participation.[1] The show had a 29-year run on national television that began in Dayton, Ohio, in 1967 and ended in New York City in 1996.

Donahue's shows often focused on issues that divide

Early life

Donahue was born on December 21, 1935,

Career

Early career

Donahue began his career in 1957 as a production assistant at

The Phil Donahue Show

On November 6, 1967, Donahue left WHIO, moving his talk program with The Phil Donahue Show on WLWD (now

After a 29-year run—26 years in syndication and nearly 7,000 one-hour daily shows—the final original episode of Donahue aired on September 13, 1996.[16]

While hosting his own program, Donahue also appeared on

U.S.–Soviet Space Bridge

In the 1980s, during the

MSNBC program

In July 2002, Donahue returned to television after seven years of retirement to host a show called Donahue on MSNBC.[21] On February 25, 2003, MSNBC canceled the show.[22][23] Soon after the show's cancellation, an internal MSNBC memo was leaked to the press stating that Donahue should be fired because he opposed the imminent

Body of War

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 2006, Donahue served as co-director with independent filmmaker

Other appearances

In June 2013, Donahue and numerous other celebrities appeared in a video showing support for Chelsea Manning.[28][29]

Donahue was interviewed for the documentary film

On May 24 and May 25, 2016, Donahue spoke at Ralph Nader's "Breaking Through Power" conference at DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C.[31][32][33]

Honors

Donahue was nominated for 20

Personal life

Donahue's 1958 marriage to Margaret Cooney produced five children – Michael, Kevin, Daniel, Mary Rose, and James – but ended in divorce in 1975. She returned to her native New Mexico, remarried, and retired from public view.

Donahue married actress Marlo Thomas on May 21, 1980.[38] He and Thomas had no children together.

In 1999, Donahue was one of the lead candidates to host the game show Greed along with Keith Olbermann, but Chuck Woolery was hired instead.[39]

Regarding his religion, Donahue had stated: "I will always be a Catholic. But I want my church to join the human race and finally walk away from this anti-sexual theology."[2] He also said that he is not "a very good Catholic", and that he did not think it was necessary to have his first marriage annulled.[2] He had expressed admiration of Pope Francis.[40]

In early August 2014, Donahue's youngest son, James Donahue, died suddenly at the age of 51 due to a

Death

Donahue died following a long illness at his home on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City, on August 18, 2024, at the age of 88. Donahue's death was confirmed by a family spokesperson, Susie Arons, who said Donahue died "peacefully following a long illness," surrounded by family members and "his beloved Golden retriever, Charlie."[42][43][15]

References

- ^ "Donahue's Last Hurrah : People.com". People. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Questions for Phil Donahue. By David Wallis. The New York Times. Published April 14, 2002.

- ^ a b "The Titans of Talk". Oprah.com. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time". TV Guide. No. December 14–20. 1996.

- ^ ISBN 9780313295850. Retrieved September 20, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 0-292-78176-8

- ISBN 0-8147-5683-2

- ^ "Donahue Gets Crowd Riled up at N.C. State Graduation". May 19, 2003.

- ^ "PHIL DONAHUE". Archive of American Television. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- YouTube.

- ^ Dave Wendt (October 7, 2007). "Yippies For Nixon". Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2016 – via YouTube.

- YouTube.

- YouTube.

- ^ Mike Gardner (June 18, 2008). "Donahue/Pozner: Chomsky (Part One)". Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Haberman, Clyde (August 19, 2024). "Phil Donahue, Talk Host Who Made Audiences Part of the Show, Dies at 88". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "R.I.P. Phil Donahue, legendary talk show host". AV Club.

- ^ Hampton, Deon J. (August 19, 2024). "Phil Donahue, talk show host pioneer and husband of Marlo Thomas, dies at 88". NBC News. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Phil Donahue: "We reached out instead of lashed out" Russia, Beyond the Headlines, http://rbth.ru, December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Phil Donahue | Biography, Photos, Movies, TV, Credits". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^ Gasyuk, Alexander (December 7, 2012). "Phil Donahue: "We reached out instead of lashed out"". Russia Beyond. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ Sherman, Gabriel, "Chasing Fox," New York magazine, October 3, 2010.

- ^ Carter, Bill (February 26, 2003). "MSNBC Cancels the Phil Donahue Talk Show". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Collins, Dan (February 25, 2003). "Phil Donahue Gets The Ax". CBS News. Associated Press. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Poniewozik, James, "In the Obama Era, Will the Media Change Too?" Time, January 15, 2009.

- ^ Naureckas, Jim "MSNBC’s Racism Is OK, Peace Activism Is Not" FAIR, April 1, 2003.

- ^ Poniewozik, James, "Watching the Not-Watchdogs,"Time, April 26, 2007.

- ^ Melidonian, Teni. 15 Docs Move Ahead in 2007 Oscar Race Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences official website. 2007-11-19. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ^ "Celeb video: 'I am Bradley Manning'". Politico. June 19, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ I am Bradley Manning (June 18, 2013). "I am Bradley Manning (full HD)". Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Maloof, John (Director), Siskel, Charlie (Director) (September 9, 2013). Finding Vivian Maier (Motion picture).

- ^ "Breaking Through Power". Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ Breaking Through Power Day 2. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Ralph Nader: Breaking through power: Join together to mobilize against wars of aggression". CT Insider. May 26, 2016.

- ^ "Phil Donahue". Television Academy. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "President Biden Announces Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". The White House. May 3, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

- ^ "The Washington Post | Donahue's Dilemma". The Washington Post.

- ^ Dayton, University of. "National Spotlight Falls on Erma Bombeck: Parade.com, Podcasts Interview Family, Phil Donahue and Writers". PR Newswire.

- ^ Ravo, Nick, "Eyesore or Landmark? The House Donahue Razed", The New York Times, July 10, 1988

- ^ Nedeff, Adam. Game Shows FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About the Pioneers, the Scandals, the Hosts, and the Jackpots. Milwaukee: Applause, 2018, page 306.

- ^ Tippett, Krista (December 12, 2013). "Phil Donahue: Transformation, On-Screen and Off". On Being Project.

- ^ Moss, Meredith (August 11, 2014). "James "Jim" Patrick Donahue, son of TV's Phil Donahue, dies at 51". Dayton Daily News. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Bryan. "Pioneering daytime TV host Phil Donahue dies at 88". USA Today.

- ^ Hampton, Deon J. (August 19, 2024). "Phil Donahue, talk show host pioneer and husband of Marlo Thomas, dies at 88". NBC News. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

Further reading

- Donahue, Phil (1979). Donahue: My Own Story.

External links

- Phil Donahue at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Phil Donahue – U.S. Talk-Show Host at the Wayback Machine (archived September 23, 2013) from Museum of Broadcast Communications

- Phil Donahue at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Phil Donahue discography at Discogs