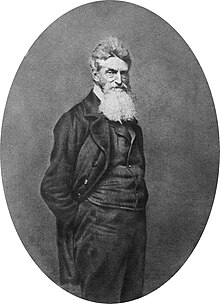

Sidney Edgerton

Sidney Edgerton | |

|---|---|

| In office March 4, 1859 – March 3, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin F. Leiter |

| Succeeded by | Rufus P. Spalding |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 17, 1818 Cazenovia, New York, US |

| Died | July 19, 1900 (aged 81) Akron, Ohio, US |

| Resting place | Tallmadge Cemetery, Tallmadge, Ohio |

| Political party | Free Soil (1848–1856) Republican (1856–1900) |

| Spouse | Mary Wright Edgerton |

| Children | Martha Edgerton Rolfe Plassmann |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer, Judge, Teacher |

| Signature | |

Sidney Edgerton (August 17, 1818 – July 19, 1900) was an American politician, lawyer, judge and teacher from

He was a sickly child that was not expected to survive; burial clothing was ordered for him. He survived and, eventually, moved to Ohio. He became a lawyer, and was involved in both the Free Soil Party and the Republican Party. After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Edgerton was invited, by Brown's family, to settle Brown's affairs. He never was able to meet with Brown. He had a successful career as a politician, and after his term ended in the Territory of Montana, Edgerton returned to Ohio. He served as a lawyer in his home state until his death in 1900.

Early life

Edgerton was born in

Early career

In 1844, he moved to

Political career

Edgerton was a delegate to the convention that formed the

House of Representatives and John Brown

Edgerton began his House term in 1859.[6] As an abolitionist, he was at risk of attack; when his term began, he purchased a sword for his defense.[12] The sword was held, secretly, inside a walking cane.[8] As an ardent anti-slavery member of the House of Representatives, Edgerton made numerous speeches about its abolition. After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Edgerton was asked by Brown's family to come and settle his affairs.[13] This was very dangerous, as Edgerton was anti-slavery. Edgerton went by train, and was joined by Congressman Alexander Boteler and Congressman H. G. Blake. While on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, Boteler was told that the men did not need to go on. Boteler and Blake listened to the advice, but Edgerton refused to go back.[14]

On his arrival at

American Civil War

During the Civil War, Edgerton served briefly as colonel in the Ohio Militia. Edgerton was one of the Squirrel Hunters, expert shots from Ohio, and served at the Defense of Cincinnati.[6][18] Edgerton served as both a U.S. Congressman and soldier at the same time, during the first few years of the war.[6]

Territory of Idaho

On March 6, 1863, Edgerton was nominated by President

After arriving in

Territory of Montana

Before leaving

Lincoln appointed Edgerton on June 22, 1864, and Edgerton found out on his arrival at

In 1865, Edgerton began to have to deal with threats from Native Americans. General Patrick Connor was sent to handle these threats. He led an expedition against the Sioux and Cheyenne Indians, who were disrupting travelers along the Bozeman Trail.[33] Edgerton then issued a proclamation for five hundred volunteers to help defend immigrants. Numerous other battles were fought, and numerous treaties were signed between the Government of the Territory of Montana and the Native Americans.[33]

In 1865, Edgerton was forced to go East to secure funds for the territory.

Montana Vigilantes

After numerous acts of lawlessness, and with no established court system, Edgerton supported his nephew, Wilbur F. Sanders, and other residents of Bannack and Virginia City as they organized the Vigilantes.[22] This group began meeting in secret, and began trying and lynching suspected criminals. On January 10, 1864, members of the Vigilance Committee traveled to Sheriff Henry Plummer's home. Plummer was suspected of murder, and the men coaxed him from his sickbed. They then grabbed him, and brought him to a gallows he had constructed for hangings. Then the men put a noose over his neck, and hanged him next to two of his deputies who were also accused of being road agents.[22][38] Along with the lynching of Plummer, the Montana Vigilantes hanged 22 road agents.[39] After these actions Edgerton's nephew, Wilbur F. Sanders, was forced to defend the group in Utah courts.[31]

Death

After returning to Akron, Ohio, with his family in the Fall of 1865, Edgerton went back to his law practice.[13][40] He was involved in his law practice until his death on July 19, 1900. He is buried in Tallmadge Cemetery in Tallmadge, Ohio.[6][28]

Notes

- ^ Between September 1865 and October 1866, Thomas F. Meagher served as Acting Governor.

Citations

- ^ a b Plassman 1900, p. 331.

- ^ a b Phillips 1951, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Plassman 1900, p. 332.

- ^ a b National Cyclopaedia 1901, p. 78.

- ^ Upton pp. 354–355

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Goodman p. 251

- ^ Taylor p. 216

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Allen pp. 123–134

- ^ Thompson p. 17

- ^ Smith p. 49–50

- ^ Lane 1892, p. 180.

- ^ Plassman 1900, p. 334.

- ^ a b Dimsdale p. 248

- ^ Plassman 1900, pp. 334–336.

- ^ Plassman 1900, p. 335.

- ^ Plassman 1900, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Plassman 1900, p. 336.

- ^ Eicher p. 223

- ^ United States Senate, pp. 264, 275

- ^ Knight p. 379

- ^ a b Inflation Calculator 2009

- ^ a b c Slatta p. 273

- ^ Bancroft p. 643

- ^ a b McPherson pp. 12–13

- ^ a b Holmes pp. 113–115

- ^ Malone p. 94

- ^ Chiorazzi p. 644

- ^ a b c d Goodspeed pp. 419–420

- ^ Allen pp. 290–291

- ^ Plassman 1900, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d e Gaitis p. 430

- ^ Malone pp. 99–100

- ^ a b Bancroft pp. 692–694

- ^ Thane 1976, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b Merrill-Maker p. 163

- ^ Plassman 1900, p. 340.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana p. 390

- ^ Waldrep pp. 64–65

- ^ Morgan p. 321

- ^ Works p. 643

References

- Allen, Frederick; A decent, orderly lynching: the Montana vigilantes, University of Oklahoma Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8061-3637-5

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe, Victor, Frances Fuller; History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana: 1845–1889, History Co., 1890

- Chiorazzi, Michael, Most, Marguerite; Prestatehood Legal Materials: A Fifty-State Research Guide, Including New York City and the District of Columbia, Volumes 1 & 2, Routledge, 2006, ISBN 0-7890-2056-4

- Dimsdale, Thomas Josiah, Noyes, Alva Josiah; The vigilantes of Montana: or, Popular justice in the Rocky mountains; being a correct and impartial narrative of the chase, trial, capture, and execution of Henry Plummer's road agent band, together with accounts of the lives and crimes of many of the robbers and desperadoes, the whole being ..., State publishing co., 1915

- Eicher, John H., Eicher David J.; Civil War high commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- Gaitis, James M.; A Stout Cord and a Good Drop: A Novel of the Founding of Montana, Globe Pequot, 2006, ISBN 0-7627-4314-X

- Goodman, Rebecca, Brunsman, Barrett J.; This Day in Ohio History, Emmis Books, 2004, ISBN 1-57860-191-6

- Goodspeed, Weston Arthur; Volume 6 of The Province and the States: A History of the Province of Louisiana Under France and Spain, and of the Territories and States of the United States Formed Therefrom, The Weston historical association, 1904

- Holmes, Krys, Walter, Dave, Dailey, Susan C.; Montana: Stories of the Land, Montana Historical Society, 2008, ISBN 0-9759196-3-6

- Idaho Supreme Court, Cummins, John; Cases argued and adjudged in the Supreme Court of the territory of Idaho: January term, 1866, and January and August terms, 1867, Statesman Pub. Co., 1867

- Inflation Calculator 2009

- Knight, William Henry; Bancroft's hand-book almanac for the Pacific States, H.H. Bancroft and Company, 1864

- Lane, Samuel Alanson; Fifty years and over of Akron and Summit County: embellished by nearly six hundred engravings—portraits of pioneer settlers, prominent citizens, business, official and professional—ancient and modern views, etc.; nine-tenth's of a century of solid local history—pioneer incidents, interesting ..., Beacon Job Department, 1892

- Malone, Michael P., Roeder, Richard B., Lang, William L.; Montana: a history of two centuries, University of Washington Press, 1991, ISBN 0-295-97129-0

- McPherson, Robert; Bannack Montana, Lulu.com, 2006, ISBN 1-4116-3342-3

- Merrill-Maker, Andrea; Montana Almanac, Globe Pequot, 2005, ISBN 0-7627-3655-0

- Morgan, Ted; Shovel of Stars: The Making of the American West – 1800 to the Present, Simon & Schuster, 1996, ISBN 0-684-81492-7

- Phillips, Paul Chrisler (1951). "Sidney Edgerton". In Johnson, Allen; Malone, Dumas (eds.). Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 20. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Plassman, Martha Edgerton (1900). "Biographical sketch of Hon. Sidney Edgerton". Contributions to the Historical Society of Montana; with Its Transactions, Officers and Members. 3: 331–340. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Slatta, Richard W.; The mythical West: an encyclopedia of legend, lore, and popular culture, ABC-CLIO, 2001, ISBN 1-57607-151-0

- Smith, Joseph Patterson; History of the Republican party in Ohio, Volume 1, Lewis Publishing Company, 1898

- Taylor, William Alexander; Ohio in Congress from 1803 to 1901, with notes and sketches of senators and representatives, and other historical data and incidents, XX. Century Publishing Co., 1900

- Thane, James L. Jr. (October 1976). "An Ohio abolitionist in the Far West: Sidney Edgerton and the opening of Montana, 1863-1866". Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 67 (4): 151–162. JSTOR 40489499.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 19, Encyclopedia Americana Corp., 1919

- The National cyclopaedia of American biography: being the history of the United States as illustrated in the lives of the founders, builders, and defenders of the republic, and of the men and women who are doing the work and moulding the thought of the present time, Volume 11, J. T. White company, 1901

- Thompson, Francis M., Owens, Kenneth N.; A Tenderfoot in Montana: Reminiscences of the Gold Rush, the Vigilantes, and the Birth of Montana Territory, Montana Historical Society, 2004, ISBN 0-9721522-2-9

- United States Senate; Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, from December 1, 1862, to July 4, 1864, Government Printing Office, 1887

- Upton, Harriet Taylor, Cutler, Harry Gardner; History of the Western Reserve, Volume 1, The Lewis publishing company, 1910

- Waldrep, Christopher; The many faces of Judge Lynch: extralegal violence and punishment in America, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, ISBN 0-312-29399-2

- Works: History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana. 1890, History Co., 1890

External links

- United States Congress. "Sidney Edgerton (id: E000048)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-02-14

- "Sidney Edgerton". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-02-14.