The Black Island

| The Black Island (L'Île noire) | |

|---|---|

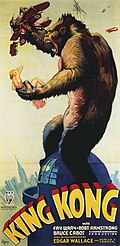

Cover of the English edition | |

| Date |

|

| Series | The Adventures of Tintin |

| Publisher | Casterman |

| Creative team | |

| Creator | Hergé |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Le Petit Vingtième |

| Date of publication | 15 April 1937 – 16 June 1938 |

| Language | French |

| Translation | |

| Publisher | Methuen |

| Date | 1966 |

| Translator |

|

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | The Broken Ear (1937) |

| Followed by | King Ottokar's Sceptre (1939) |

The Black Island (French: L'Île noire) is the seventh volume of The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle for its children's supplement Le Petit Vingtième, it was serialised weekly from April to November 1937. The story tells of young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog Snowy, who travel to England in pursuit of a gang of counterfeiters. Framed for theft and hunted by detectives Thomson and Thompson, Tintin follows the criminals to Scotland, discovering their lair on the Black Island.

The Black Island was a commercial success and was published in book form by

dramatisation of the Adventures.Synopsis

Tintin witnesses a plane land in the Belgian countryside, and is shot by the pilot when he offers his help. While he recovers in hospital, detectives

The following morning after recovering in hospital, Tintin finds electric cables and red beacons in the garden, surmising that they are there designed to attract a plane drop. At night, he lights the beacons, and a plane drops sacks of counterfeit money, revealing that Müller is part of a gang of forgers. Tintin pursues Müller and Ivan by car and by train across the country. Along the way, Thompson and Thomson try to arrest him again, but Tintin convinces them to join him in the pursuit of the criminals. When Müller takes a plane north, Tintin and Snowy try to follow, but hit a storm and crash land in rural Scotland. The detectives commandeer another plane, but discover - too late - that the man they told to fly it is actually a mechanic who has never flown before, and after a harrowing air-bound odyssey they end up crash-landing into (and winning) an aerobatics competition.[2]

Learning that Müller's plane had crashed off the coast of Kiltoch, a Scottish coastal village, Tintin travels there to continue his investigation. At Kiltoch, an old man tells him the story of Black Island — an island off the coast where a "ferocious beast" kills any visitors. Tintin and Snowy travel to the island, where they find that the "beast" is a trained gorilla named Ranko. They further discover that the forgers are using the island as their base, and radio the police for help. Although the forgers attempt to capture Tintin, the police arrive and arrest the criminals. Ranko, who was injured during Tintin's attempts to hold off the forgers, becomes docile enough to allow Tintin to bring him to a zoo.[3]

History

Background and research

Georges Remi—best known under the pen name

For his next serial, Hergé planned to put together a story that caricatured the actions of

Hergé retained the anti-German sentiment that he had first considered for King Ottokar's Sceptre through the inclusion of a German villain, Dr. Müller,

Original publication

The Black Island was first serialised in Le Petit Vingtième from 15 April to 16 November 1937 under the title Le Mystère De L'Avion Gris (The Mystery of the Grey Plane).[19] From 17 April 1938, the story was also serialised in the French Catholic newspaper, Cœurs Vaillants.[20] In 1938, Éditions Casterman collected the story together in a single hardcover volume, publishing it under the title L'Île noire (The Black Island).[20] Hergé however was unhappy with this publication due to errors throughout, most egregiously that the front cover omitted his name.[21]

The inclusion of a television in the original version would have surprised many readers. The BBC had only introduced television to Britain in the late 1930s (suspended entirely until 1946) and Belgium would not have television until 1955.[22]

Second and third versions

In the 1940s and 1950s, when Hergé's popularity had increased, he and his team at Studios Hergé redrew and coloured many of the original black-and-white Tintin adventures. They used the ligne claire ("clear line") drawing style that Hergé had developed, in this way ensuring that the earlier stories fitted in visually alongside the new Adventures of Tintin being created. Casterman published this second, colourised version of the story in 1943, reduced from 124 pages to 60.[20] This second version contained no significant changes from the original 1937 one,[22] although the black-and-white television screen that had appeared in the 1930s version was now depicted as a colour screen, despite the fact that such technology was not yet available.[23]

In the early 1960s, Hergé's English language publishers,

The new version was serialised in Tintin magazine from June to December 1965,[25] before Casterman published it in a collected volume in 1966.[20] Studios Hergé made many alterations to the illustrations as a result of De Moor's research. Reflecting the fact that television had become increasingly commonplace in Western Europe, Hergé changed the prose from "It's a television set!" to "It's only a television set!"[10] However, as colour television was not yet available in Britain, the screen on the television encountered in Britain was once again reverted to black-and-white.[23] Additionally, at least one line of dialogue was "softened" from the original version - in one scene where Tintin aims a pistol at two of the counterfeiters, he states, "Get back! And put up your hands!" compared to the original's "One more step and you're dead!".[16] The counterfeit notes that Tintin finds were also increased in value, from one pound to five pounds.[16] The multiple aircraft featured throughout the story were redrawn by Studios member Roger Leloup, who replaced the depiction of planes that were operational in the 1930s to those active at the time, such as a Percival Prentice, a D.H. Chipmunk, a Cessna 150, a Tiger Moth, and a British European Airways Hawker Siddeley Trident.[26]

The clothing worn by characters was brought up-to-date, while the old steam locomotives that were initially featured were replaced by more modern diesel or electrified alternatives.

The idea of Tintin travelling to England created a problem for English translators, as Metheun's policy had Anglicised the series by moving Tintin's home from Brussels to London. In the first act after his wounding by a smuggler pilot, Tintin is originally told by one of the Twins that "We're leaving for England." In English this becomes "We're going back to England," with no explanation as to why all the main characters were in the same continental town simultaneously.

Later publications

Casterman republished the original black-and-white version of the story in 1980, as part of their Archives Hergé collection.[14] In 1986, they then published a facsimile version of that first edition,[14] that they followed in 1996 with the publication of a facsimile of the second, 1943 edition.[28]

Critical analysis

Harry Thompson thought that The Black Island expressed a "convenient, hitherto unsuspected regard for the British" on Hergé's behalf, with Britain itself appearing as "a little quaint".[10] He thought that it "outstrips its predecessors" both artistically and comedically,[31] describing it as "one of the most popular Tintin stories".[32] He felt that some of the logically implausible slapstick scenes illustrated "the last flicker of 1920s Tintin",[31] but that the 1966 version was "a fine piece of work and one of the most beautifully drawn Tintin books".[30] Michael Farr commented on the "distinct quality and special popularity" of The Black Island.[23] He thought that the inclusion of many airplanes and a television in the first version was symptomatic of Hergé's interest in innovation and modernism.[23] Commenting on the differences between the third version of the comic and the earlier two, he thought that the latter was "strongly representative" of the artistic talents of Studios Hergé in the 1960s, but that it was nevertheless inferior, because it had replaced the "spontaneity and poetry" of the original with "over-detailed and fussily accurate" illustrations.[28]

Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier described The Black Island as "a clever little thriller" that bore similarities with the popular detective serials of the era.[33] The Lofficiers thought that the 1966 version "gained in slickness" but became less atmospheric, awarding it two out of five.[33] Biographer Benoît Peeters thought The Black Island to be "a pure detective story", describing it as "Remarkably well constructed" and highlighting that it contrasted the modern world of counterfeiters, airplanes, and television, with the mysteries of superstition and the historic castle.[34] He described it as "an adventure full of twists and turns", with the characters Thompson and Thomson being "on top form".[18] He nevertheless considered the 1966 version to be "shorter on charm" than the earlier versions.[35] Elsewhere he was more critical, stating that "under the guise of modernization, a real massacre occurred", and adding that "the new Black Island was more than just a failure; it also showed one of the limitations of the Hergéan system", in that it was obsessed with repeated redrawing.[36]

Literary critic Jean-Marie Apostolidès of Stanford University believed that The Black Island expanded on a variety of themes that Hergé had explored in his earlier work, such as the idea of counterfeiting and Snowy's fondness for whisky.[37] He thought that there was a human-animal link in the story, with Tintin's hair matching Snowy's fur in a similar manner to how Wronzoff's beard matched Ranko's fur coat.[37] However, he added that while Tintin's relationship with Snowy was wholly one based in good, Wronzoff's connection with Ranko is one rooted in evil.[38] By living on an island, Apostolidès thought that Wronzoff was like "a new Robinson Crusoe", also highlighting that it was the first use of the island theme in Hergé's work.[38] Literary critic Tom McCarthy thought that The Black Island linked to Hergé's other Adventures in various ways; he connected the counterfeit money in the story to the counterfeit idol in The Broken Ear and the fake bunker in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets.[39] He also connected Tintin's solving of the puzzle in the airman's jacket to his solving of the pirate puzzles in The Secret of the Unicorn,[40] and that in transmitting from a place of death, Ben Mor, or mort (death), it linked to Tintin's transmitting from the crypt of Marlinspike Hall in The Secret of the Unicorn.[41]

Adaptations

The Black Island is one of The Adventures of Tintin that was adapted for the second series of the animated

In 1992, a radio adaption by the

On 19 March 2010, the British TV network Channel 4 broadcast a documentary titled Dom Joly and The Black Island in which the comedian Dom Joly dressed up as Tintin and followed in Tintin's footsteps from Ostend to Sussex and then to Scotland. Reviewing the documentary in The Guardian, Tim Dowling commented: "It was amusing in parts, charming in others and a little gift for Tintinophiles everywhere. A Tintinologist, I fear, would not learn much he or she didn't already know".[45]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ Hergé 1966, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Hergé 1966, pp. 23–42.

- ^ Hergé 1966, pp. 43–62.

- ^ Peeters 1989, pp. 31–32; Thompson 1991, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Assouline 2009, pp. 22–23; Peeters 2012, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Assouline 2009, pp. 26–29; Peeters 2012, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 46.

- ^ Assouline 2009, pp. 40–41; Peeters 2012, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Thompson 1991, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e Thompson 1991, p. 77.

- ^ Goddin 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Goddin 2008, pp. 8, 11.

- ^ a b c Farr 2001, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Farr 2007, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 56; Thompson 1991, p. 77; Farr 2001, p. 71; Peeters 2012, p. 91.

- ^ a b Peeters 2012, p. 91.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c d Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Peeters 1989, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e Farr 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Thompson 1991, pp. 77–78; Farr 2001, pp. 72, 75; Peeters 2012, p. 91.

- ^ Peeters 2012, p. 293.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 78; Farr 2001, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Farr 2001, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d Farr 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 41; Farr 2001, p. 78.

- ^ a b Thompson 1991, p. 78.

- ^ a b Thompson 1991, p. 79.

- ^ Thompson 1991, p. 80.

- ^ a b Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 55.

- ^ Peeters 1989, p. 59.

- ^ Peeters 2012, pp. 293–294.

- ^ a b Apostolidès 2010, p. 89.

- ^ a b Apostolidès 2010, p. 90.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 122.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 21.

- ^ McCarthy 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 87.

- ^ a b Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 90.

- ^ Martin, Roland (28 August 2005). "The Adventures of Tintin: BBC Radio Adaptations". tintinologist.org. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Dowling 2010.

Bibliography

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010) [2006]. The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. Jocelyn Hoy (translator). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

- Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

- Dowling, Tim (19 March 2010). "Dom Joly and the Black Island". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- ISBN 978-1-4052-3264-7.

- ISBN 978-0-86719-706-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4052-0618-1.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

- ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

External links

- The Black Island at the Official Tintin Website

- The Black Island at Tintinologist.org

- The Black Island, TV-series part 1 at IMDb

- The Black Island, TV-series part 2 at IMDb