Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University | |

Jenny Martinez | |

Academic staff | 2,323 (Fall 2023)[6] |

|---|---|

Administrative staff | 18,369 (Fall 2023)[7] |

| Students | 17,529 (Fall 2023)[6] |

| Undergraduates | 7,841 (Fall 2023)[6] |

| Postgraduates | 9,688 (Fall 2023)[6] |

| Location | , , 37°25′39″N 122°10′12″W / 37.42750°N 122.17000°W |

| Campus | |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper | The Stanford Daily |

| Colors | Cardinal Red & White[9] |

| Nickname | Cardinal |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Stanford Tree (unofficial)[10] |

| Website | stanford |

Stanford University (officially Leland Stanford Junior University)[11][12] is a private research university in Stanford, California. It was founded in 1885 by Leland Stanford—a railroad magnate who served as the eighth governor of and then-incumbent senator from California—and his wife, Jane, in memory of their only child, Leland Jr.[2] Stanford has an 8,180-acre (3,310-hectare) campus, among the largest in the nation.

The university admitted its first students in 1891,[2][3] opening as a coeducational and non-denominational institution. It struggled financially after Leland's death in 1893 and again after much of the campus was damaged by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[13] Following World War II, Frederick Terman, the university's provost, inspired and supported faculty and graduates entrepreneurialism to build a self-sufficient local industry, which would later be known as Silicon Valley.[14] Stanford established Stanford Research Park in 1951 as the world's first university research park which became "the epicenter of Silicon Valley".[15][16][17][18]

The university is organized around seven schools on the same campus. It also houses the

Stanford is particularly noted for its entrepreneurship and is one of the most successful universities in attracting funding for start-ups.[22][23][24][25][26] Stanford alumni have founded numerous companies, which combined produce more than $2.7 trillion in annual revenue.[27][28][29] 58 Nobel laureates, 29 Turing Award laureates,[note 1] and 8 Fields Medalists have been affiliated with Stanford as alumni, faculty, or staff.[50]

Stanford is the

History

Stanford University was founded in 1885 by Leland and Jane Stanford, dedicated to the memory of Leland Stanford Jr., their only child. The institution opened in 1891 on Stanford's previous Palo Alto farm. Jane and Leland Stanford modeled their university after the great Eastern universities, specifically Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Stanford was referred to as the "Cornell of the West" in 1891 due to a majority of its faculty being former Cornell affiliates, including its first president, David Starr Jordan, and second president, John Casper Branner. Both Cornell and Stanford were among the first to make higher education accessible, non-sectarian, and open to women as well as men. Cornell is credited as one of the first American universities to adopt that radical departure from traditional education, and Stanford became an early adopter as well.[54]

From an architectural point of view, the Stanfords, particularly Jane, wanted their university to look different from the eastern ones, which had often sought to emulate the style of English university buildings. They specified in the founding grant[55] that the buildings should "be like the old adobe houses of the early Spanish days; they will be one-storied; they will have deep window seats and open fireplaces, and the roofs will be covered with the familiar dark red tiles." This guides the campus buildings to this day. The Stanfords also hired renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who previously designed the Cornell campus, to design the Stanford campus.[56]

When Leland Stanford died in 1893, the continued existence of the university was in jeopardy due to a federal lawsuit against his estate, but Jane Stanford insisted the university remain in operation throughout the financial crisis.[57][58] The university suffered major damage from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; most of the damage was repaired, but a new library and gymnasium were demolished, and some original features of Memorial Church and the Quad were never restored.[59]

During the early-twentieth century, the university added four professional graduate schools.

In the 1940s and 1950s,

In the 1950s, Stanford intentionally reduced and restricted Jewish admissions, and for decades, denied and dismissed claims from students, parents, and alumni that they were doing so.[71] Stanford issued its first institutional apology to the Jewish community in 2022 after an internal task force confirmed that the university deliberately discriminated against Jewish applicants, while also misleading those who expressed concerns, including students, parents, alumni, and the ADL.[72][73]

Wallace Sterling was president 1949 to 1968. He oversaw the growth of Stanford from a financially troubled regional university to a financially sound, internationally recognized academic powerhouse, "the Harvard of the West".[74] Achievements during Sterling's tenure included:

- Moving the Stanford Medical Schoolfrom a small, inadequate campus in San Francisco to a new facility on the Stanford campus which was fully integrated into the university to an unusual degree for medical schools.

- Establishing the Stanford Industrial Park (now the Stanford Research Park) and the Stanford Shopping Center on leased University land, thus stabilizing the university's finances. The Stanford Industrial Park, together with the university's aggressive pursuit of government research grants, helped to spur the development of Silicon Valley.

- Increasing the number of students receiving financial aid from less than 5% when he took office to more than one-third when he retired.

- Increasing the size of the student body from 8,300 to 11,300 and the size of the tenured faculty from 322 to 974.

- Launching the PACE fundraising program, the largest such program ever undertaken by any university up to that time.

- Launching a building boom on campus that included a new bookstore, post office, student union, dormitories, a faculty club, and many academic buildings.

- Creating the Overseas Campus program for undergraduates in 1958.

In the 1960s, Stanford rose from a regional university to one of the most prestigious in the United States, "when it appeared on lists of the "top ten" universities in America... This swift rise to performance [was] understood at the time as related directly to the university's defense contracts..."[75] Stanford was once considered a school for "the wealthy",[76] but controversies in later decades damaged its reputation. The 1971 Stanford prison experiment was criticized as unethical,[77] and the misuse of government funds from 1981 resulted in severe penalties for the school's research funding[78][79] and the resignation of Stanford President Donald Kennedy in 1992.[80]

Land

Most of Stanford is on an 8,180-acre (12.8 sq mi; 33.1 km2)[6] campus, one of the largest in the United States.[note 2] It is on the San Francisco Peninsula, in the northwest part of the Santa Clara Valley (Silicon Valley) approximately 37 miles (60 km) southeast of San Francisco and approximately 20 miles (30 km) northwest of San Jose. $4.5 billion was received by Stanford in 2006 and spent more than $2.1 billion in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties. In 2008, 60% of this land remained undeveloped.[83]

Stanford's main campus includes a census-designated place within unincorporated Santa Clara County,[84] although some of the university land (such as the Stanford Shopping Center and the Stanford Research Park) is within the city limits of Palo Alto. The campus also includes much land in unincorporated San Mateo County (including the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve), as well as in the city limits of Menlo Park (Stanford Hills neighborhood), Woodside, and Portola Valley.[85]

The central campus includes a seasonal lake (

Central campus

The central academic campus is adjacent to Palo Alto,

Non-central campus

On the founding grant:

- Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve is a 1,200-acre (490 ha) natural reserve south of the central campus owned by the university and used by wildlife biologists for research. Researchers and students are involved in biological research. Professors can teach the importance of biological research to the biological community. The primary goal is to understand the system of the natural Earth.[90]

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is a facility west of the central campus operated by the university for the Department of Energy. It contains the longest linear particle accelerator in the world, 2 miles (3.2 km) on 426 acres (172 ha) of land.[91]

Off the founding grant:

- Study abroad locations: unlike typical study abroad programs, Stanford itself operates in several locations around the world; thus, each location has Stanford faculty-in-residence and staff in addition to students, creating a "mini-Stanford."[94]

- Redwood City campus for many of the university's administrative offices in

- The Bass Center in Washington, D.C. provides a base, including housing, for the Stanford in Washington program for undergraduates.[99] It includes a small art gallery open to the public.[100]

- China: Stanford Center at Peking University, housed in the Lee Jung Sen Building, is a small center for researchers and students in collaboration with Peking University.[101][102]

Faculty residences

Many Stanford faculty members live in the "Faculty Ghetto", within walking or biking distance of campus.

Other uses

Some of the land is managed to provide revenue for the university such as the Stanford Shopping Center and the Stanford Research Park. Stanford land is also leased for a token rent by the Palo Alto Unified School District for several schools including Palo Alto High School and Gunn High School.[105] El Camino Park, the oldest Palo Alto city park, is also on Stanford land.[106] Stanford also has the Stanford Golf Course[107] and Stanford Red Barn Equestrian Center[108] used by Stanford athletics though the golf course can also be used by the general public.

Landmarks

Contemporary campus landmarks include the

-

Interior of the Stanford Memorial Church at the center of the Main Quad

-

Hoover Tower, at 285 feet (87 m), the tallest building on campus

-

The new Stanford Stadium, site of home football games

-

Stanford Quad with Memorial Church in the background

-

The Dish, a 150 feet (46 m) diameter radio telescope on the Stanford foothills overlooking the main campus

-

White Memorial Fountain (The Claw)

Administration and organization

Stanford is a private, non-profit university administered as a

The board appoints a president to serve as the chief executive officer of the university, to prescribe the duties of professors and course of study, to manage financial and business affairs, and to appoint nine vice presidents.

As of 2022, the university is organized into seven academic schools.

The Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) is the student government for Stanford and all registered students are members. Its elected leadership consists of the Undergraduate Senate elected by the undergraduate students, the Graduate Student Council elected by the graduate students, and the President and Vice President elected as a

Endowment and donations

The university's endowment, managed by the Stanford Management Company, was valued at $36.5 billion as of August 31, 2023.[4] Payouts from the Stanford endowment covered approximately 22% of university expenses in the 2023 fiscal year.[4] In the 2018 NACUBO-TIAA survey of colleges and universities in the United States and Canada, only Harvard University, the University of Texas System, and Yale University had larger endowments than Stanford.[135]

In 2006, President John L. Hennessy launched a five-year campaign called the Stanford Challenge, which reached its $4.3 billion fundraising goal in 2009, two years ahead of time, but continued fundraising for the duration of the campaign. It concluded on December 31, 2011, having raised $6.23 billion and breaking the previous campaign fundraising record of $3.88 billion held by Yale.[136][137] Specifically, the campaign raised $253.7 million for undergraduate financial aid, as well as $2.33 billion for its initiative in "Seeking Solutions" to global problems, $1.61 billion for "Educating Leaders" by improving K-12 education, and $2.11 billion for "Foundation of Excellence" aimed at providing academic support for Stanford students and faculty. Funds supported 366 new fellowships for graduate students, 139 new endowed chairs for faculty, and 38 new or renovated buildings. The new funding also enabled the construction of a facility for stem cell research; a new campus for the business school; an expansion of the law school; a new Engineering Quad; a new art and art history building; an on-campus concert hall; the new Cantor Arts Center; and a planned expansion of the medical school, among other things.[138][139] In 2012, the university raised $1.035 billion, becoming the first school to raise more than a billion dollars in a year.[140]

In April 2022, Stanford University announced a $75 million donation, in support of a multidisciplinary neurodegenerative brain disease research initiative at the university's Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. The donation came from Nike co-founder Phil Knight and his wife Penny; hence The Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience will explore cognitive declines from diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.[141]

Academics

Admissions

| First-time fall freshman statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[142] | 2020[143] | 2019[144] | 2018[145] | 2017[146] | |||||

| Applicants | 55,471 | 45,227 | 47,498 | 47,452 | 44,073 | ||||

| Admits | 2,190 | 2,349 | 2,062 | 2,071 | 2,085 | ||||

| Admit rate | 3.9% | 5.19% | 4.34% | 4.36% | 4.73% | ||||

| Enrolled | 1,757 | 1,607 | 1,701 | 1,697 | 1,703 | ||||

| Yield | 80.23% | 68.41% | 82.49% | 81.94% | 81.68% | ||||

| SAT range | 1420–1570 | 1420–1550 | 1440–1550 | 1420–1570 | 1390–1540 | ||||

| ACT range | 32–35 | 31–35 | 32–35 | 32–35 | 32–35 | ||||

Stanford is considered by US News to be 'most selective' with an acceptance rate of 4%, one of the lowest among US universities. Half of the applicants accepted to Stanford have an SAT score between 1440 and 1570 or an ACT score between 32 and 35. Admissions officials consider a student's GPA to be an important academic factor, with emphasis on an applicant's high school class rank and letters of recommendation.[147] In terms of non-academic materials as of 2019, Stanford ranks extracurricular activities, talent/ability and character/personal qualities as 'very important' in making first-time, first-year admission decisions, while ranking the interview, whether the applicant is a first-generation university applicant, legacy preferences, volunteer work and work experience as 'considered'.[144] Of those students accepted to Stanford's Class of 2026, 1,736 chose to attend, of which 21% were first-generation college students.

Stanford's admission process is need-blind for U.S. citizens and permanent residents;[148] while it is not need-blind for international students, 64% are on need-based aid, with an average aid package of $31,411.[149] In 2012, the university awarded $126 million in need-based financial aid to 3,485 students, with an average aid package of $40,460.[149] Eighty percent of students receive some form of financial aid.[149] Stanford has a no-loan policy.[149] For undergraduates admitted starting in 2015, Stanford waives tuition, room, and board for most families with incomes below $65,000, and most families with incomes below $125,000 are not required to pay tuition; those with incomes up to $150,000 may have tuition significantly reduced.[150] Seventeen percent of students receive Pell Grants,[149] a common measure of low-income students at a college. In 2022, Stanford started its first dual-enrollment computer science program for high school students from low-income communities[151] as a pilot project which then inspired the founding of the Qualia Global Scholars Program.[152] Stanford plans to expand the program to include courses in Structured Liberal Education and writing.[151]

Teaching and learning

Stanford follows a quarter system with the autumn quarter usually beginning in late September and the spring quarter ending in mid-June.[153] The full-time, four-year undergraduate program has arts and sciences focus with high graduate student coexistence.[153] Stanford is accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges with the latest review in 2023.[154]

Research centers and institutes

Stanford is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity."[153] The university's research expenditure in fiscal years of 2021–2022 was $1.82 billion and the total number of sponsored projects was 7,900+.[155] As of 2016, the Office of the Vice Provost and Dean of Research oversaw eighteen independent laboratories, centers, and institutes. Kathryn Ann Moler is the key person for leading those research centers for choosing problems, faculty members, and students. Funding is also provided for undergraduate and graduate students by those labs, centers, and institutes for collaborative research.[156]

Other Stanford-affiliated institutions include the

Stanford is home to the

Together with

Libraries and digital resources

As of 2014, Stanford University Libraries (SUL) has twenty-four libraries in total. The Hoover Institution Library and Archives is a research center based on history of twentieth century.[161] Stanford University Libraries (SUL) held a collection of more than 9.3 million volumes, nearly 300,000 rare or special books, 1.5 million e-books, 2.5 million audiovisual materials, 77,000 serials, nearly 6 million microform holdings, thousands of other digital resources.[162] and 516,620 journal, 526,414 images, 11,000 software collection, 100,000 videos etc. .[163]

The main library in the SU library system is the

Arts

Stanford is home to the

The Stanford music department sponsors many ensembles, including five choirs, the Stanford Symphony Orchestra,

Reputation and rankings

Forbes[176] | 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. News & World Report[177] | 3 (tie) | |

| Washington Monthly[178] | 2 | |

| WSJ / College Pulse[179] | 4 | |

| Global | ||

| ARWU[180] | 2 | |

| QS[181] | 5 | |

| THE[182] | 2 | |

| U.S. News & World Report[183] | 3 | |

Slate in 2014 dubbed Stanford as "the Harvard of the 21st century".[184] In the same year The New York Times dubbed Harvard as the "Stanford of the East". In that article titled To Young Minds of Today, Harvard Is the Stanford of the East, The New York Times concluded that "Stanford University has become America's 'it' school, by measures that Harvard once dominated."[185] In 2019, Stanford University took 1st place on Reuters' list of the World's Most Innovative Universities for the fifth consecutive year.[186] In 2022, Washington Monthly ranked Stanford at 1st position in their annual list of top universities in the United States.[187] In a 2022 survey by The Princeton Review, Stanford was ranked 1st among the top ten "dream colleges" of America, and was considered to be the ultimate "dream college" of both students and parents.[188][189] Stanford Graduate School of Business was ranked 1st in the list of America's best business schools by Bloomberg for 2022.[190][191]

From polls of college applicants done by The Princeton Review, every year from 2013 to 2020 the most commonly named "dream college" for students was Stanford; separately, parents, too, most frequently named Stanford their ultimate "dream college."[192][193] Globally Stanford is also ranked among the top universities in the world. The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) ranked Stanford second in the world (after Harvard) most years from 2003 to 2020.[194] Times Higher Education recognizes Stanford as one of the world's "six super brands" on its World Reputation Rankings, along with Berkeley, Cambridge, Harvard, MIT, and Oxford.[195][196]

Discoveries and innovation

Natural sciences

- deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) – Arthur Kornberg discovered the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid, and won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1959 for his work at Stanford.[197]By studying bacteria, Kornberg succeeded in isolating DNA polymerase in 1956–an enzyme that is active in the formation of DNA.

- First human growth hormone and hepatitis B vaccine.

- Laser – Arthur Leonard Schawlow shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physics with Nicolaas Bloembergen and Kai Siegbahn for his work on lasers.[200][201]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance – Felix Bloch developed new methods for nuclear magnetic precision measurements, which are the underlying principles of the MRI.[202][203]

Computer and applied sciences

- Stanford Research Institute, formerly part of Stanford but on a separate campus, was the site of one of the four original ARPANET nodes.[204][205] In the early 1970s, Bob Kahn & Vint Cerf's research project about Internetworking, later DARPA formulated it to the TCP(Transmission Control Program).[206]

- Frequency modulation synthesis – John Chowning of the Music department invented the FM music synthesis algorithm in 1967, and Stanford later licensed it to Yamaha Corporation.[208][209]

- Google – Google began in January 1996 as a research project by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, when they were both PhD students at Stanford.[210] They were working on the Stanford Digital Library Project (SDLP) which is started in 1999. The SDLP's goal was "to develop the enabling technologies for a single, integrated and universal digital library"[211] and it was funded through the National Science Foundation, among other federal agencies.[212] Today, Google stands as one of the most valuable brands in the world.

- Klystron tube – invented by the brothers Russell and Sigurd Varian at Stanford.[213] Their prototype was completed and demonstrated successfully on August 30, 1937.[214] Upon publication in 1939, news of the klystron immediately influenced the work of U.S. and UK researchers working on radar equipment.[215][216]

- SUN workstation – Andy Bechtolsheim designed the SUN workstation,[218] for the Stanford University Network communications project as a personal CAD workstation,[219] which led to Sun Microsystems.

Businesses and entrepreneurship

Stanford is one of the most successful universities in creating companies and licensing its inventions to existing companies, and it is often considered a model for technology transfer.[22][23] Stanford's Office of Technology Licensing is responsible for commercializing university research, intellectual property, and university-developed projects. The university is described as having a strong venture culture in which students are encouraged, and often funded, to launch their own companies.[24] Companies founded by Stanford alumni generate more than $2.7 trillion in annual revenue and have created some 5.4 million jobs since the 1930s.[220] When combined, these companies would form the tenth-largest economy in the world.[28] Some companies closely associated with Stanford and their connections include:

- William R. Hewlett (B.S, PhD) and David Packard (M.S)[221]

- Silicon Graphics, 1981: co-founders James H. Clark (Associate Professor) and several of his graduate students[222]

- Sun Microsystems, 1982:[223] co-founders Vinod Khosla (M.B.A), Andy Bechtolsheim (PhD) and Scott McNealy (M.B.A)

- Cisco, 1984:[224] co-founders Leonard Bosack (M.S) and Sandy Lerner (M.S) were in charge of the Stanford Computer Science and the Graduate School of Business computer operations groups, respectively, when the hardware was developed[225]

- Yahoo!, 1994:[226] co-founders Jerry Yang (B.S, M.S) and David Filo (M.S)

- Google, 1998:[227] co-founders Larry Page (M.S) and Sergey Brin (M.S)

- LinkedIn, 2002:[228] co-founders Reid Hoffman (B.S), Konstantin Guericke (B.S, M.S), Eric Lee (B.S), and Alan Liu (B.S)

- Instagram, 2010:[229] co-founders Kevin Systrom (B.S) and Mike Krieger (B.S)[230]

- Bobby Murphy (B.S)[231]

- Coursera, 2012:[232] co-founders Andrew Ng (Associate Professor) and Daphne Koller (Professor, PhD)

Student life

Student body

| Race and ethnicity[233] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 29% | ||

| Asian | 25% | ||

| Hispanic | 17% | ||

| Non-resident Foreign nationals | 11% | ||

| Other[a] | 10% | ||

| Black | 7% | ||

| Native American | 1% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 18% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 82% | ||

Stanford enrolled 6,996 undergraduate[149] and 10,253 graduate students[149] as of the 2019–2020 school year. Women made up 50.4% of undergraduates and 41.5% of graduate students.[149] In the same academic year, the freshman retention rate was 99%. Stanford awarded 1,819 undergraduate degrees, 2,393 master's degrees, 770 doctoral degrees, and 3270 professional degrees in the 2018–2019 school year.[149] The four-year graduation rate for the class of 2017 cohort was 72.9%, and the six-year rate was 94.4%.[149] The relatively low four-year graduation rate is a function of the university's coterminal degree (or "coterm") program, which allows students to earn a master's degree as a 1-to-2-year extension of their undergraduate program.[234] As of 2010, fifteen percent of undergraduates were first-generation students.[235]

Dormitories and student housing

As of 2013, 89% of undergraduate students lived in on-campus university housing. First-year undergraduates are required to live on campus, and all undergraduates are guaranteed housing for all four undergraduate years.

Most student residences are just outside the campus core, within ten minutes (on foot or bike) of most classrooms and libraries. Some are reserved for freshmen, sophomores, or upper-class students and some are open to all four classes. Most residences are co-ed; seven are all-male

Several residences are considered theme houses. The Academic, Language, and Culture Houses include EAST (Education and Society Themed House), Hammarskjöld (International Themed House), Haus Mitteleuropa (Central European Themed House), La Casa Italiana (Italian Language and Culture), La Maison Française (French Language and Culture House), Slavianskii Dom (Slavic/East European Themed House), Storey (Human Biology Themed House), and Yost (Spanish Language and Culture). Cross-Cultural Themed Houses include Casa Zapata (Chicano/Latino Theme in Stern Hall), Muwekma-tah-ruk (American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Themed House), Okada (Asian-American Themed House in Wilbur Hall), and Ujamaa (Black/African-American Themed House in Lagunita Court). Focus Houses include

Co-ops or "Self-Ops" are another housing option. These houses feature cooperative living, where residents and eating associates each contribute work to keep the house running, such as cooking meals or cleaning shared spaces. These houses have unique themes around which their community is centered. Many co-ops are hubs of music, art and philosophy. The co-ops on campus are 576 Alvarado Row (formerly Chi Theta Chi), Columbae, Enchanted Broccoli Forest (EBF), Hammarskjöld, Kairos, Terra (the unofficial LGBT house),[243] and Synergy.[244] Phi Sigma, at 1018 Campus Drive was formerly Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity, but in 1973 became a Self-Op.[245]

As of 2015, around 55 percent of the graduate student population lived on campus.

Athletics

As of 2016, Stanford had sixteen male varsity sports and twenty female varsity sports,

Its traditional sports rival is the

Traditions

- "Hail, Stanford, Hail!" is the Stanford hymn sometimes sung at ceremonies or adapted by the various university singing groups. It was written in 1892 by mechanical engineering professor Albert W. Smith and his wife, Mary Roberts Smith (in 1896 she earned the first Stanford doctorate in economics and later became associate professor of sociology), but was not officially adopted until after a performance on campus in March 1902 by the

- Big Game: The central football rivalry between Stanford and UC Berkeley. First played in 1892, and for a time played by the universities' rugby teams, it is one of the oldest college rivalries in the United States.

- The Stanford Axe: A trophy earned by the winner of Big Game, exchanged only as necessary. The axe originated in 1899 when Stanford yell leader Billy Erb wielded a lumberman's axe to inspire the team. Stanford lost, and the Axe was stolen by Berkeley students following the game. In 1930, Stanford students staged an elaborate heist to recover the Axe. In 1933, the schools agreed to exchange it as a prize for winning Big Game. As of 2021, a restaurant centrally located on Stanford's campus is named "The Axe and Palm" in reference to the Axe.[259]

- Big Game Gaieties: In the week ahead of Big Game, a 90-minute original musical (written, composed, produced, and performed by the students of Ram's Head Theatrical Society) is performed in Memorial Auditorium.[260]

- Full Moon on the Quad: An annual event at Main Quad, where students gather to kiss one another starting at midnight. Typically organized by the junior class cabinet, the festivities include live entertainment, such as music and dance performances.[261]

- The Stanford Marriage Pact: An annual matchmaking event where thousands of students complete a questionnaire about their values and are subsequently matched with the best person for them to make a "marriage pact" with.[262][263][264][265]

- Fountain Hopping: At any time of year, students tour Stanford's main campus fountains to dip their feet or swim in some of the university's 25 fountains.[261][266][267]

- Mausoleum Party: An annual Halloween party at the Stanford Mausoleum, the final resting place of Leland Stanford Jr. and his parents. A 20-year tradition, the Mausoleum party was on hiatus from 2002 to 2005 due to a lack of funding, but was revived in 2006.[261][268] In 2008, it was hosted in Old Union rather than at the actual Mausoleum, because rain prohibited generators from being rented.[269] In 2009, after fundraising efforts by the Junior Class Presidents and the ASSU Executive, the event was able to return to the Mausoleum despite facing budget cuts earlier in the year.[270]

- Wacky Walk: At commencement, graduates forgo a more traditional entrance and instead stride into Stanford Stadium in a large procession wearing wacky costumes.[267][271]

- Steam Tunneling: Stanford has a network of underground brick-lined tunnels that conduct central heating to more than 200 buildings via steam pipes. Students sometimes navigate the corridors, rooms, and locked gates, carrying flashlights and water bottles.[272] Stanford Magazine named steam tunneling one of the "101 things you must do" before graduating from the Farm in 2000.[273]

- Band Run: An annual festivity at the beginning of the school year, where the band picks up freshmen from dorms across campus while stopping to perform at each location, culminating in a finale performance at Main Quad.[261]

- Viennese Ball: a formal It is now open to all students.

- The long-unofficial motto of Stanford, selected by President Jordan, is "Die Luft der Freiheit weht."[275] Translated from the German language, this quotation from Ulrich von Hutten means, "The wind of freedom blows." The motto was controversial during World War I, when anything in German was suspect; at that time the university disavowed that this motto was official.[1] It was made official by way of incorporation into an official seal by the board of trustees in December 2002.[276]

- Degree of Uncommon Man/Uncommon Woman: Stanford does not award honorary degrees,

- Former campus traditions include the Big Game bonfire on Lake Lagunita (a seasonal lake usually dry in the fall), which was formally ended in 1997 because of the presence of endangered salamanders in the lake bed.[280]

Religious life

Students and staff at Stanford are of many different religions. The Stanford Office for Religious Life's mission is "to guide, nurture and enhance spiritual, religious and ethical life within the Stanford University community" by promoting enriching dialogue, meaningful ritual, and enduring friendships among people of all religious backgrounds. It is headed by a dean with the assistance of a senior associate dean and an associate dean. Stanford Memorial Church, in the center of campus, has a Sunday University Public Worship service (UPW) usually in the "Protestant Ecumenical Christian" tradition where the Memorial Church Choir sings and a sermon is preached usually by one of the Stanford deans for Religious Life. UPW sometimes has multifaith services.[281] In addition, the church is used by the Catholic community and by some of the other Christian denominations at Stanford. Weddings happen most Saturdays and the university has for over twenty years allowed blessings of same-gender relationships and now legal weddings.

In addition to the church, the Office for Religious Life has a Center for Inter-Religious Community, Learning, and Experiences (CIRCLE) on the third floor of Old Union. It offers a common room, an interfaith sanctuary, a seminar room, a student lounge area, and a reading room, as well as offices housing a number of Stanford Associated Religions (SAR) member groups and the Senior Associate Dean and Associate Dean for Religious Life. Most though not all religious student groups belong to SAR. The SAR directory includes organizations that serve atheist,

Greek life

Fraternities and sororities have been active on the Stanford campus since 1891 when the university first opened. In 1944, University President Donald Tresidder banned all Stanford sororities due to extreme competition.[286] However, following Title IX, the Board of Trustees lifted the 33-year ban on sororities in 1977.[287] Students are not permitted to join a fraternity or sorority until spring quarter of their freshman year.[288]

As of 2016, Stanford had thirty-one Greek organizations, including fourteen sororities and sixteen fraternities. Nine of the Greek organizations were housed (eight in University-owned houses and one, Sigma Chi, in their own house, although the land is owned by the university).[289] Five chapters were members of the African American Fraternal and Sororal Association, eleven chapters were members of the Interfraternity Council, seven chapters belonged to the Intersorority Council, and six chapters belonged to the Multicultural Greek Council.[290]

- Stanford is home to two unhoused historically National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC or "Divine Nine") sororities (Alpha Kappa Alpha, and Delta Sigma Theta) and two unhoused NPHC fraternities (Alpha Phi Alpha and Kappa Alpha Psi). These fraternities and sororities operate under the African American Fraternal Sororal Association (AAFSA) at Stanford.[291]

- Seven historically National Panhellenic Conference (NPC) sororities, four of which are unhoused (Alpha Phi, Alpha Epsilon Phi, Chi Omega, and Kappa Kappa Gamma) and three of which are housed (Delta Delta Delta, Kappa Alpha Theta, and Pi Beta Phi) call Stanford home. These sororities operate under the Stanford Inter-sorority Council (ISC).[292]

- Eleven historically National Interfraternity Conference (NIC) fraternities are also represented at Stanford, including five unhoused fraternities (Alpha Epsilon Pi, Delta Kappa Epsilon, Delta Tau Delta, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, and Kappa Alpha Order), and four housed fraternities (Sigma Phi Epsilon, Kappa Sigma, Phi Kappa Psi, and Sigma Nu). These fraternities operate under the Stanford Inter-fraternity Council (IFC).[293]

- There are also four unhoused Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) sororities on campus (alpha Kappa Delta Phi, Lambda Theta Nu, Sigma Psi Zeta, and Sigma Theta Psi), as well as two unhoused MGC fraternities (Gamma Zeta Alpha and Lambda Phi Epsilon). Lambda Phi Epsilon is recognized by the National Interfraternity Conference (NIC).[294]

Student groups

As of 2020, Stanford had more than 600 student organizations.[295] Groups are often, though not always, partially funded by the university via allocations directed by the student government organization, the ASSU. These funds include "special fees," which are decided by a Spring Quarter vote by the student body. Groups span athletics and recreation, careers/pre-professional, community service, ethnic/cultural, fraternities and sororities, health and counseling, media and publications, the arts, political and social awareness, and religious and philosophical organizations. In contrast to many other selective universities, Stanford policy mandates that all recognized student clubs be "broadly open" for all interested students to join.[296][297][298][299]

Stanford is home to a set of student journalism publications. The Stanford Daily is a student-run daily newspaper and has been published since the university was founded in 1892.[300] The student-run radio station, KZSU Stanford 90.1 FM, features freeform music programming, sports commentary, and news segments; it started in 1947 as an AM radio station.[301] The Stanford Review is a conservative student newspaper founded in 1987.[302] The Fountain Hopper (FoHo) is a financially independent, anonymous student-run campus rag publication, notable for having broken the Brock Turner story.[303] Stanford hosts numerous environmental and sustainability-oriented student groups, including Students for a Sustainable Stanford, Students for Environmental and Racial Justice, and Stanford Energy Club.[304] Stanford is a member of the Ivy Plus Sustainability Consortium, through which it has committed to best-practice sharing and the ongoing exchange of campus sustainability solutions along with other member institutions.[305]

Stanford is also home to a large number of pre-professional student organizations, organized around missions from startup incubation to paid consulting. The Business Association of Stanford Entrepreneurial Students (BASES) is one of the largest professional organizations in Silicon Valley, with over 5,000 members.[306] Its goal is to support the next generation of entrepreneurs.[307] StartX is a non-profit startup accelerator for student and faculty-led startups.[308] It is staffed primarily by students.[309] Stanford Women In Business (SWIB) is an on-campus business organization, aimed at helping Stanford women find paths to success in the generally male-dominated technology industry.[310] Stanford Marketing is a student group that provides students hands-on training through research and strategy consulting projects with Fortune 500 clients, as well as workshops led by people from industry and professors in the Stanford Graduate School of Business.[311][312] Stanford Finance provides mentoring and internships for students who want to enter a career in finance. Stanford Pre Business Association is intended to build connections among industry, alumni, and student communities.[313]

Stanford is also home to several academic groups focused on government and politics, including Stanford in Government and Stanford Women in Politics. The Stanford Society for Latin American Politics is Stanford's first student organization focused on the region's political, economic, and social developments, working to increase the representation and study of Latin America on campus. Former guest speakers include José Mujica and Gustavo Petro.[314] Other groups include:

- The Stanford Axe Committee is the official guardian of the Stanford Axe and the rest of the time assists the Stanford Band as a supplementary spirit group. It has existed since 1982.[315]

- Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) which hosts the annual Stanford Powwow started in 1971. This is the largest student-run event on campus and the largest student-run powwow in the country.[316][317]

- The Stanford Improvisors (SImps for short) teach and perform improvisational theatre on campus and in the surrounding community.[318] In 2014 the group finished second in the Golden Gate Regional College Improv tournament[319] and they have since been invited twice to perform at the annual San Francisco Improv Festival.[320]

- Asha for Education is a national student group founded in 1991. It focuses mainly on education in India and supporting nonprofit organizations that work mainly in the education sector. Asha's Stanford chapter organizes events like Holi as well as lectures by prominent leaders from India on the university campus.[321][322][323]

Safety

Stanford's Department of Public Safety is responsible for law enforcement and safety on the main campus. Its deputy sheriffs are

Campus sexual misconduct

In 2014, Stanford was the tenth highest in the nation in "total of reports of rape" on their main campus, with 26 reports of rape.[329] In Stanford's 2015 Campus Climate Survey, 4.7 percent of female undergraduates reported experiencing sexual assault as defined by the university, and 32.9 percent reported experiencing sexual misconduct.[330] According to the survey, 85% of perpetrators of misconduct were Stanford students and 80% were men.[330] Perpetrators of sexual misconduct were frequently aided by alcohol or drugs, according to the survey: "Nearly three-fourths of the students whose responses were categorized as sexual assault indicated that the act was accomplished by a person or persons taking advantage of them when they were drunk or high, according to the survey. Close to 70 percent of students who reported an experience of sexual misconduct involving nonconsensual penetration and/or oral sex indicated the same."[330]

Associated Students of Stanford and student and alumni activists with the anti-rape group Stand with Leah criticized the survey methodology for downgrading incidents involving alcohol if students did not check two separate boxes indicating they were both intoxicated and incapacity while sexually assaulted.[330] Reporting on the Brock Turner rape case, a reporter from The Washington Post analyzed campus rape reports submitted by universities to the U.S. Department of Education, and found that Stanford was one of the top ten universities in campus rapes in 2014, with 26 reported that year, but when analyzed by rapes per 1000 students, Stanford was not among the top ten.[329]

People v. Turner

On the night of January 17–18, 2015, 22-year-old Chanel Miller, who was visiting the campus to attend a party at the Kappa Alpha fraternity, was sexually assaulted by Brock Turner, a nineteen-year-old freshman student-athlete from Ohio. Two Stanford graduate students witnessed the attack and intervened; when Turner attempted to flee the two held him down on the ground until police arrived.[331] Stanford immediately referred the case to prosecutors and offered Miller counseling, and within two weeks had barred Turner from campus after conducting an investigation.[332] Turner was convicted on three felony charges in March 2016 and in June 2016 he received a jail sentence of six months and was declared a sex offender, requiring him to register as such for the rest of his life; prosecutors had sought a six-year prison sentence out of the maximum 14 years that was possible.[333] The case and the relatively lenient sentence drew nationwide attention.[334] Two years later, the judge in the case, Stanford graduate Aaron Persky, was recalled by the voters.[335][336]

Joe Lonsdale

In February 2015, Elise Clougherty filed a sexual assault and harassment lawsuit against venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale.[337][338] Lonsdale and Clougherty entered into a relationship in the spring of 2012 when she was a junior and he was her mentor in a Stanford entrepreneurship course.[338] By the spring of 2013 Clougherty had broken off the relationship and filed charges at Stanford that Lonsdale had broken the Stanford policy against consensual relationships between students and faculty and that he had sexually assaulted and harassed her, which resulted in Lonsdale being banned from Stanford for 10 years.[338] Lonsdale challenged Stanford's finding that he had sexually assaulted and harassed her and Stanford rescinded that finding and the campus ban in the fall of 2015.[339] Clougherty withdrew her suit that fall as well.[340]

Notable people

As of late 2021, Stanford had 2,288 tenure-line faculty, senior fellows, center fellows, and medical center faculty.[341]

Award laureates and scholars

Stanford's current community of scholars includes:

- 22 Nobel Prize laureates (as of October 2022, 58 affiliates in total);[341]

- 174 members of the National Academy of Sciences;[341]

- 113 members of National Academy of Engineering;[341]

- 90 members of National Academy of Medicine;[341]

- 303 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences;[341]

- 10 recipients of the National Medal of Science;[341]

- 3 recipients of the National Medal of Technology;[341]

- 6 recipients of the National Humanities Medal;[341]

- 47 members of American Philosophical Society;[341]

- 56 fellows of the American Physics Society (since 1995);[342]

- 4 Pulitzer Prize winners;[341]

- 33 MacArthur Fellows;[341]

- 6 Wolf Foundation Prize winners;[341]

- 2 ACL Lifetime Achievement Award winners;[343]

- 14 AAAI fellows;[344]

- 2 Presidential Medal of Freedom winners.[341][345]

Stanford's faculty and former faculty includes 48 Nobel laureates,

- Notable Stanford alumni include:

-

Herbert Hoover (BS 1895), 31st President of the United States, founder of Hoover Institution at Stanford. Trustee of Stanford for nearly 50 years.[355]

-

William Rehnquist (BA 1948, MA 1948, LLB 1952) 16th Chief Justice of the United States

-

Sandra Day O'Connor (BA 1950, LLB 1952), Former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

-

Rishi Sunak (MBA 2006), Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

-

Yukio Hatoyama (PhD 1976), Former Prime Minister of Japan

-

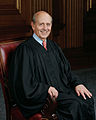

Stephen Breyer (BA 1959), Former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

-

Larry Page (MS 1998), founder of Alphabet Inc.

-

Sergey Brin (MS 1995), founder of Alphabet Inc.

-

Netflix Inc.

-

Nike Inc.

-

LinkedIn Corporation

- Notable present and past Stanford faculty include:

See also

- List of universities by number of billionaire alumni

- List of colleges and universities in California

- S*, a collaboration between seven universities and the Karolinska Institute for training in bioinformatics and genomics

- Stanford School

Explanatory notes

- ^ Undergraduate school alumni who received the Turing Award:

- Vint Cerf: BS Math Stanford 1965; MS CS UCLA 1970; PhD CS UCLA 1972.[30]

- Allen Newell: BS Physics Stanford 1949; PhD Carnegie Institute of Technology 1957.[31]

- Martin Hellman: BE New York University 1966, MS Stanford University 1967, Ph.D. Stanford University 1969, all in electrical engineering. Professor at Stanford 1971–1996.[32]

- John Hopcroft: BS Seattle University; MS EE Stanford 1962, Phd EE Stanford 1964.[33]

- Barbara Liskov: BSc Berkeley 1961; PhD Stanford.[34]

- Raj Reddy: BS from Guindy College of Engineering (Madras, India) 1958; M Tech, University of New South Wales 1960; Ph.D. Stanford 1966.[35]

- Ronald Rivest: BA Yale 1969; PhD Stanford 1974.[36]

- Robert Tarjan: BS Caltech 1969; MS Stanford 1971, PhD 1972.[37]

- Whitfield Diffie: BS Mathematics Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1965. Visiting scholar at Stanford from 2009–2010 and an affiliate from 2010–2012; currently, a consulting professor at CISAC (The Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University).[38]

- Doug Engelbart: BS EE Oregon State University 1948; MS EE Berkeley 1953; PhD Berkeley 1955. Researcher/Director at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) 1957–1977; Director (Bootstrap Project) at Stanford University 1989–1990.[39]

- Edward Feigenbaum: BS Carnegie Institute of Technology 1956, Ph.D. Carnegie Institute of Technology 1960. Associate Professor at Stanford 1965–1968; Professor at Stanford 1969–2000; Professor Emeritus at Stanford (2000–present).[40]

- Robert W. Floyd: BA 1953, BSc Physics, both from the University of Chicago. Professor at Stanford (1968–1994).[41]

- Sir Antony Hoare: Undergraduate at Oxford University. Visiting Professor at Stanford 1973.[42]

- Alan Kay: BA/BS from the University of Colorado at Boulder, Ph.D. 1969 from the University of Utah. Researcher at Stanford 1969–1971.[43]

- John McCarthy: BS Math, Caltech; PhD Princeton. Assistant Professor at Stanford 1953–1955; Professor at Stanford 1962–2011.[44]

- Robin Milner: BSc 1956 from Cambridge University. Researcher at Stanford University 1971–1972.[45]

- Amir Pnueli: BSc Math from Technion 1962, PhD Weizmann Institute of Science 1967. Instructor at Stanford 1967; Visitor at Stanford 1970[46]

- Dana Scott: BA Berkeley 1954, Ph.D. Princeton 1958. Associate Professor at Stanford 1963–1967.[47]

- Niklaus Wirth: BS Swiss Federal Institute of Technology 1959, MSC Universite Laval, Canada, 1960; Ph.D. Berkeley 1963. Assistant Professor at Stanford University 1963–1967.[48]

- Andrew Yao: BS physics National University of Taiwan 1967; AM Physics Harvard 1969; Ph.D. Physics, Harvard 1972; Ph.D. CS University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign 1975 Assistant Professor at Stanford University 1976–1981; Professor at Stanford University 1982–1986.[49]

- ^ It is often stated that Stanford has the largest contiguous campus in the world (or the United States)[81][82] but that depends on definitions. Berry College with over 26,000 acres (40.6 sq mi; 105.2 km2), Paul Smith's College with 14,200 acres (22.2 sq mi; 57.5 km2), and the United States Air Force Academy with 18,500 acres (7,500 ha) are larger but are not usually classified as universities. Duke University at 8,610 acres (13.5 sq mi; 34.8 km2) does have more land, but it is not contiguous. However, the University of the South has over 13,000 acres (20.3 sq mi; 52.6 km2).

- ^ The rules governing the board have changed over time. The original 24 trustees were appointed for life in 1885 by the Stanfords, as were some of the subsequent replacements. In 1899 Jane Stanford changed the maximum number of trustees from 24 to 15 and set the term of office to 10 years. On June 1, 1903, she resigned her powers as founder and the board took on its full powers. In the 1950s, the board decided that its fifteen members were not sufficient to do all the work needed and in March 1954 petitioned the courts to raise the maximum number to 23, of whom 20 would be regular trustees serving 10-year terms and 3 would be alumni trustees serving 5-year terms. In 1970 another petition was successfully made to have the number raised to a maximum of 35 (with a minimum of 25), that all trustees would be regular trustees, and that the university president would be a trustee ex officio.[114] The last original trustee, Timothy Hopkins, died in 1936; the last life trustee, Joseph D. Grant (appointed in 1891), died in 1942.[115]

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- Pell grantintended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

- ^ a b c Casper, Gerhard (October 5, 1995). Die Luft der Freiheit weht—On and Off (Speech). Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c "History: Stanford University". Stanford University. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Chapter 1: The University and the Faculty". Faculty Handbook. Stanford University. September 7, 2016. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c As of August 31, 2023. "Stanford University reports return on investment portfolio, value of endowment". October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Finances – Facts". Stanford University. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Stanford Facts". Stanford University. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Staff – Facts". Stanford University. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "IPEDS-Stanford University". Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "Color". Stanford Identity Toolkit. Stanford University. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ The Stanford Tree is the mascot of the band but not the university.

- ^ "'Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax – 2013' (IRS Form 990)" (PDF). foundationcenter.org. 990s.foundationcenter.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "The founding grant: with amendments, legislation, and court decrees". Stanford Digital Repository. November 26, 1987. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "History – Part 2 (The New Century): Stanford University". Stanford.edu. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "History – Part 3 (The Rise of Silicon Valley): Stanford University". Stanford.edu. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ https://books.google.it/books?id=Fdmj3_XcqmMC&pg=PA122&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ https://www.fastcompany.com/1686634/stanford-universitys-unique-economic-engine

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK158815/

- ^ https://techcrunch.com/2015/09/04/what-will-stanford-be-without-silicon-valley/?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAHpKtkBnoQv5Nn0q8oe9zHsWFpK_0F-6YETm4KINuuI2irVUFYYfe4RD-vfxyi6CeoOZuVWor628PYjJn7xjNlm2k-x8l5UiNpkkVHQ_eXiZuW0Mhw9Kl-3OfV0L9pqgK8coiwqaj59Tthgtc--MCJSjsVQQ0MnMUZW82jw3UU9s

- ^ Athletics, Stanford (May 24, 2022). "Simply Dominant". gostanford.com. Stanford University. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Conference, Pac-12 (July 2, 2018). "Stanford wins 24th-consecutive Directors' Cup". Pac-12 News. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Athletics, Stanford (July 1, 2016). "Olympic Medal History". Stanford University Athletics. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Nigel Page. The Making of a Licensing Legend: Stanford University's Office of Technology Licensing Archived June 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Chapter 17.13 in Sharing the Art of IP Management. Globe White Page Ltd, London, U.K. 2007

- ^ ISBN 9781139046930

- ^ a b McBride, Sarah (December 12, 2014). "Special Report: At Stanford, venture capital reaches into the dorm". Reuters. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Devaney, Tim (December 3, 2012). "One University To Rule Them All: Stanford Tops Startup List – ReadWrite". ReadWrite. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ "The University Entrepreneurship Report – Alumni of Top Universities Rake in $12.6 Billion Across 559 Deals". CB Insights Research. October 29, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ "Box". stanford.app.box.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Silver, Caleb (March 18, 2020). "The Top 20 Economies in the World". Investopedia. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Krieger, Lisa M. (October 24, 2012). "Stanford alumni's companies combined equal tenth largest economy on the planet". The Mercury News. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ "Vinton Cerf – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Allen Newell". acm.org.

- ^ "Martin Hellman". acm.org.

- ^ "John E Hopcroft". acm.org.

- ^ "Barbara Liskov". acm.org.

- ^ "Raj Reddy – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Ronald L Rivest – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Robert E Tarjan – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Whitfield Diffie". acm.org.

- ^ "Douglas Engelbart". acm.org.

- ^ "Edward A Feigenbaum – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Robert W. Floyd – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ Lee, J.A.N. "Charles Antony Richard (Tony) Hoare". IEEE Computer Society. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "Alan Kay". acm.org.

- ^ "John McCarthy". acm.org.

- ^ "A J Milner – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Amir Pnueli". acm.org.

- ^ "Dana S Scott – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Niklaus E. Wirth". acm.org.

- ^ "Andrew C Yao – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (August 12, 2014). "Stanford's Maryam Mirzakhani wins Fields Medal". Stanford Report. Stanford University. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ Elkins, Kathleen (May 18, 2018). "More billionaires went to Harvard than to Stanford, MIT and Yale combined". cnbc. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^

- "Top Producers". us.fulbrightonline.org. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "US Rhodes Scholars Over Time". www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Harvard, Stanford, Yale Graduate Most Members of Congress".

- ISBN 978-0-8047-1639-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-1639-0.

- ^ "Founding Grant with Amendments" (PDF). November 11, 1885. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ University, Office of the Registrar-Stanford. "Stanford Bulletin - Stanford University". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- LCCN 59013788.

- ^ Nilan, Roxanne (1979). "Jane Lathrop Stanford and the Domestication of Stanford University, 1893–1905". San Jose Studies. 5 (1): 7–30.

- ^ "Post-destruction decisions". Stanford University and the 1906 Earthquake. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Stanford University School of Medicine and the Predecessor Schools: An Historical Perspective. Part IV: Cooper Medical College 1883–1912. Chapter 30. Consolidation with Stanford University 1906 – 1912". Stanford Medical History Center. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "Stanford University School of Medicine and the Predecessor Schools: An Historical Perspective Part V. The Stanford Era 1909– Chapter 37. The New Stanford Medical Center Planning and Building 1953 – 1959". Stanford Medical History Center. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "ABA-Approved Law Schools by Year". By Year Approved. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ "History". Stanford Graduate School of Education. September 17, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Our History". Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Stanford University". Encyclopedia Britannica. November 27, 2019.

- ISBN 978-0262622110.

- ^ Sandelin, Jon. "Co-Evolution of Stanford University & the Silicon Valley: 1950 to Today" (PDF). WIPO. Stanford University Office of Technology Licensing. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ Gillmor, C. Stewart. Fred Terman at Stanford: Building a Discipline, a University, and Silicon Valley. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2004. Print.

- ^ Tajnai, Carolyn (May 1985). "Fred Terman, the Father of Silicon Valley". Stanford Computer Forum. Carolyn Terman. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Salahieh, Nouran (October 13, 2022). "Stanford University apologizes for limiting Jewish student admissions during the 1950s". CNN.

- ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Dremann, Sue (October 14, 2022). "Stanford apologizes for historical bias against Jewish students". Palo Alto Weekly.

- ^ Roxanne L. Nilan, and Cassius L. Kirk Jr., Stanford's Wallace Sterling: Portrait of a Presidency 1949-1968 (Stanford Up, 2023),

- ISBN 978-0-520-91790-3.

- ProQuest 1435607944. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ The Belmont Report, Office of the Secretary, Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects for Biomedical and Behavioral Research, April 18, 1979

- ^ "Stanford, government agree to settle a dispute over research costs". stanford.edu. News.stanford.edu. October 18, 1994. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Merl, Jean (July 30, 1991). "Stanford President, Beset by Controversies, Will Quit: Education: Donald Kennedy to step down next year. Research scandal, harassment charge plagued university". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Folkenflik, David (November 20, 1994). "What Happened to Stanford's Expense Scandal?". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "Virtual Tours". Stanford University. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ Keck, Gayle. "Stanford: A Haven in Silicon Valley" (PDF). Executive Travel Magazine.

- ^ Report, Stanford (October 9, 2008). "University spent $2.1 billion locally in 2006, study shows". stanford.edu. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

Stanford Univ

- ^ "Stanford Facts: The Stanford Lands". stanford.edu. Stanford University. 2013. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Enthoven, Julia (December 5, 2012). "University monitors Lake Lagunita after fall storms". stanforddaily.com. The Stanford Daily. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Stanford students rejoice over full Lake Lag". January 9, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Krieger, Lisa M (December 28, 2008). "Felt Lake: Muddy portal to Stanford's past". The Mercury News. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "Palo Alto General Plan Update: Land Use Element" (PDF). City of Palo Alto. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "About the Preserve". jrbp.stanford. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ "About SLAC". slac.stanford.edu. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Howe, Kevin (May 10, 2011). "Pacific Grove". montereyherald.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Julian, Sam (August 17, 2010). "Graduate student uncovers Hopkins' immigrant history". news.stanford. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ "Faculty-in-Residence : Bing Overseas Study Program". bosp.stanford.edu. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Falk, Joshua (July 29, 2010). "Redwood City campus remains undeveloped". The Stanford Daily. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Chesley, Kate (September 10, 2013). "Redwood City approves Stanford office building proposals". Stanford Report. Stanford University. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Kadvany, Elena (December 10, 2015). "Stanford's Redwood City campus moves closer to reality". Palo Alto Weekly. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ University, Stanford (January 31, 2020). "Stanford Redwood City campus evokes warmth of university". Stanford News. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Bass Center Overview | Stanford in Washington". siw.stanford.edu. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "The Art Gallery at Stanford in Washington | Stanford in Washington". siw.stanford.edu. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "About the Center". Stanford Center at Peking. Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ "The Lee Jung Sen Building". Stanford Center at Peking University. Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ "Stanford Faculty Staff Housing". Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Housing Program Changes 2022". Stanford Login. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Breitrose, Charlie (December 2, 1998). "SCHOOLS: District wants Stanford land for school". Palo Alto Weekly. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "El Camino Park". City of Palo Alto. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Stanford Golf Course – Stanford, CA". www.stanfordgolfcourse.com. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "Stanford Red Barn Equestrian Center | Recreation and Wellness". Stanford Red Barn Equestrian Center. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Kathleen J. (August 5, 2010). "Machinists restoring White Memorial Fountain, aka The Claw, develop an affinity for the campus icon". Stanford News. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Kathleen J. (June 10, 2011). "Sculptor returns for update on White Plaza fountain makeover". Stanford News. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Kofman, Nicole (May 22, 2012). "Frolicking in fountains". Stanford Daily. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Steffen, Nancy L. (May 20, 1964). "The Claw: White Plaza Dedication". Stanford Daily. Retrieved December 11, 2016. Has information on the White brothers that slightly corrects some of the facts in other articles.

- ^ "Stanford Facts: Administration & Finances". facts.stanford.edu. Stanford University. May 2, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ a b "Stanford University – The Founding Grant with Amendments, Legislation, and Court Decrees" (PDF). Stanford University. 1987. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "Joseph D. Grant House – Parks and Recreation – County of Santa Clara". www.sccgov.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019. Joseph D. Grant County Park (Santa Clara) is named for him.

- ^ "University Governance and Organization". bulletin.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Stanford University Facts—Finances and Governance". Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 15, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ "University Governance and Organization". bulletin.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "Biography". September 1, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ "Stanford alum, business school dean Jonathan Levin named Stanford president". Stanford University. April 4, 2024.

- ^ "About the Provost". Office of the Provost. Stanford University. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ "About the Office | Office of the Provost". Provost Stanford. Stanford University. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ "Jenny S. Martinez appointed Stanford provost". August 23, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ "Stanford's Seven Schools". Stanford University. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "School of Humanities and Sciences | Stanford University". exploredegrees.stanford.edu. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "School of Engineering | Stanford University". exploredegrees.stanford.edu. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability". Stanford Bulletin. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ "School of Law". Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "School of Medicine". Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ "School of Education". Stanford Graduate School of Education. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "School of Business". Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ "The Faculty Senate – University Governance and Organization". facultysenate.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ "University Governance and Organization". bulletin.stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ISBN 0-313-27228-X.

- ^ U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2017 to FY 2018 (PDF), National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA, retrieved October 9, 2019

- ^ Kiley, Kevin (February 8, 2012). "Stanford Raises $6.2 Billion in Five-Year Campaign". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ "Stanford Nets $6.2 billion in 5-year Campaign". The Huffington Post. February 9, 2012.

- ^ Stanford, © Stanford University; Notice, California 94305 Copyright Complaints Trademark (February 8, 2012). "Stanford concludes transformative campaign". Stanford University.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Stanford Challenge – Final Report – By the Numbers: Overall". Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ Chea, Terence (February 20, 2013). "Stanford University is 1st College to raise $1B". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Stanford University launches $75 million brain disease initiative". Philanthropy News Digest. April 28, 2022. Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ "Stanford University Common Data Set 2021–2022" (PDF). Stanford Office of Institutional Research and Decision Support. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 26, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

For common datasets from 2008–present, see ucomm.stanford.edu/cds/

- ^ "Stanford University Common Data Set 2020–2021" (PDF). Stanford Office of Institutional Research and Decision Support. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

For common datasets from 2008–present, see ucomm.stanford.edu/cds/

- ^ a b "Stanford University Common Data Set 2019–2020" (PDF). Stanford Office of Institutional Research and Decision Support. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

For common datasets from 2008–present, see ucomm.stanford.edu/cds/

- ^ "Stanford University Common Data Set 2018–2019" (PDF). Stanford Office of Institutional Research and Decision Support. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

For common datasets from 2008–present, see ucomm.stanford.edu/cds/

- ^ "Stanford University Common Data Set 2017–2018" (PDF). Stanford Office of Institutional Research and Decision Support. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

For common datasets from 2008–present, see ucomm.stanford.edu/cds/

- US News. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Undergraduate Basics". Financial Aid. Stanford University. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Stanford Common Data Set 2019–2020". Stanford University. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Stanford offers admission to 2,144 students, expands financial aid program". Stanford News. March 27, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "High school students welcomed to the Stanford family". Stanford Report. January 26, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Sha, Brian (April 10, 2022). "What I learned teaching a Stanford computer science class to high school students". stanforddaily.com. The Stanford Daily. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Carnegie Classifications—Stanford University". Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ "Accreditation". wasc.stanford.edu. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ "Stanford Facts". stanford.edu. Stanford University. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ "Interdisciplinary Laboratories, Centers, and Institutes". Stanford University. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ "Former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis to Return to Hoover Institution". U.S. News. 2019.

- ^ "The King Papers Project". The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute. June 11, 2014. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ "Center for Ocean Solutions". Stanford Woods. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ "CNN Business News". CNN. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ "The Hoover Institution Library and Archives".

- ^ "Stanford Facts: Stanford Libraries". Stanford University. 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Books, media, & more".

- ^ "Books".

- ^ "Stanford University Press (SUP)". Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ "Rodin! The Complete Stanford Collection". Cantor Arts Center. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Atherton, CA. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (September 12, 2014). "Anderson Collection pieces lock in a home at Stanford". SFGate. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Teicholz, Tom (December 28, 2018). "The Museum of Hunk, Moo & Putter: The Anderson Collection at Stanford will Rock You". Forbes. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "The Stanford Improvisors". Stanford.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ "About the Mendicants". Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "About Counterpoint". Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "About Fleet Street". Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017. Because Fleet Street maintains Stanford songs as a regular part of its performing repertoire, the university used the group as ambassadors during the university's centennial celebration and commissioned an album, entitled Up Toward Mountains Higher (1999), of Stanford songs which were sent to alumni around the world.

- ^ "About Raagapella". Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's 2023 Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2023". Forbes. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ^ "2023 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "ShanghaiRanking's 2023 Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2024: Top global universities". Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ "2022-23 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ Oremus, Will (April 15, 2013). "Silicon Is the New Ivy". Slate. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (May 29, 2014). "To Young Minds of Today, Harvard Is the Stanford of the East". The New York Times. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ "The World's Most Innovative Universities 2019". Reuters.

- ^ "2022 National University Rankings".

- ^ "These are the country's 'dream' colleges, but price remains the top concern". CNBC. March 27, 2022.

- ^ "2022 College Hopes & Worries Press Release".

- ^ "Stanford, 1st in Bloomberg Businessweek's 2022–23 US B-School Rankings". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ "These Are the US's Best Business Schools". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ "College Hopes & Worries Press Release". Princeton Review. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "2020 College Hopes & Worries Press Release". Princeton Review. March 17, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2022". Shanghai Ranking. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Baty, Phil (January 1, 1990). "Birds? Planes? No, colossal 'super-brands': Top Six Universities". Times Higher Education. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Ross, Duncan (May 10, 2016). "World University Rankings blog: how the 'university superbrands' compare". Times Higher Education. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959". nobelprize.org. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-4541-9. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- PMID 24043817.

- ^ "Arthur L. Schawlow". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ "Network (SUNet — The Stanford University Network)". Stanford University Information Technology Services. July 16, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "Stanford University". University Discoveries. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "ARPANET – A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication" (PDF).

- S2CID 205049153. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Johnstone, Robert (January 1994). "Johnstone, Robert". academia. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ "An Introduction To FM". stanford. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ "Google Milestones". Google, Inc. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- ^ "The Stanford Digital Library Technologies". stanford. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- ^ The Stanford Integrated Digital Library Project, Award Abstract #9411306, September 1, 1994, through August 31, 1999 (Estimated), award amount $521,111,001

- ^ "The Klystron: A Microwave Source of Surprising Range and Endurance" (PDF). slac stanford. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Varian, Dorothy. "The Inventor and the Pilot". Pacific Books, 1983 p. 187

- ^ "Russell and Sigurd Varian: Inventing The Klystron And Saving Civilization". electronicdesign. November 22, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Guide to the Russell and Sigurd Varian Papers". cdlib. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ISBN 1-57356-521-0.

- ISBN 9780471297130. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Andreas Bechtolsheim; Forest Baskett; Vaughan Pratt (March 1982). "The SUN Workstation Architecture". Stanford University Computer systems Laboratory Technical Report No. 229. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Stanford alumni create nearly $3 trillion in economic impact each year". stanford. October 24, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "HPE History". hpe. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ISBN 978-1579582357.

- ^ "Sun Microsystems Getting Started". sun. Archived from the original on August 27, 2006. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Toscano, Paul (April 17, 2013). "Cisco Co-Founder". CNBC. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ Duffy, Jim. "Critical milestones in Cisco history". Network World. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Goel, Vindu (July 24, 2016). "Yahoo's Sale to Verizon Ends an Era". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ "How we started and where we are today & Our history in depth – Google". about.google. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Founders". LinkedIn. May 5, 2003. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2022.