Typhoon Ma-on (2004)

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (November 2023) |

Typhoon Ma-on on October 8 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 3, 2004 |

| Dissipated | October 10, 2004 |

| Very strong typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 185 km/h (115 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 920 hPa (mbar); 27.17 inHg |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 260 km/h (160 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 898 hPa (mbar); 26.52 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 7 |

| Missing | 2 |

| Damage | $623 million (2004 USD) |

| Areas affected | Japan, Alaska |

| IBTrACS | |

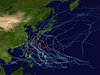

Part of the 2004 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Ma-on, known in the

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Typhoon Ma-on originated from a weak

After losing a defined low-level circulation early on October 10,

Preparations, impact and aftermath

Japan

As Typhoon Ma-on began turning to the north on October 8 towards Japan, the JMA warned residents in the

Typhoon Ma-on was the eighth of a record-breaking ten landfalling typhoons in Japan during the 2004 season.[15] Of these storms, Ma-on was the only system to strike eastern areas of the nation directly and the second-strongest, with a landfall pressure of 950 mb (hPa; 28.06 inHg).[16][17] Collectively, these storms resulted in 214 fatalities and over 2,000 injuries. Widespread and extensive damage to housing and infrastructure occurred with well over 200,000 homes damaged or destroyed and financial losses in excess of ¥564 billion (US$5 billion).[16]

The typhoon produced record-breaking wind across the

Torrential rains accompanied the storm, with several areas reporting rainfall rates in excess of 60 mm (2.4 in) per hour. A local record of 89 mm (3.5 in) per hour was measured in

Landslides triggered by the heavy rains caused widespread disruptions in the nation as well as one fatality in

Approximately 180,000

Widespread disruptions to rail service in eastern Japan resulted from the typhoon. Service along the

In Gunma Prefecture a man was injured after being blown off his roof in Ōta while trying to repair a gutter. A few homes were flooded and damage in the prefecture amounted to ¥41.2 million.[28] One person sustained minor injuries in Tokorozawa. Flooding in Saitama Prefecture affected 1,562 homes, 159 severely, and hundreds of roads were left impassible. In Iwatsuki, the Ayase River overflowed its banks and prompted the evacuation of 74 people. Damage to agriculture and forestry amounted to ¥253.5 million.[29] Six people were injured, one seriously, in Ibaraki Prefecture, by high winds. Numerous landslides occurred, some of which blocked rivers and caused flooding; others blocked rail lines. A total of 191 homes were affected by floods, 53 of which sustained damage. In terms of agriculture, 4,606 ha (11,380 acres) of crops flooded and losses reached ¥866 million.[30]

A car carrying four people was swept away by a landslide in

Additional, though minor, damage occurred in Akita,[35] Aomori,[36] Gifu,[37] Mie,[38] Niigata,[39] Shimane,[40] Tochigi,[41] Wakayama,[42] and Yamagata prefectures.[43] According to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA), 135 homes were destroyed while 4,796 sustained damage. Another report from Rika Nenpyo indicated far greater damage: 5,553 homes destroyed and 7,843 others damaged. Relative to the intensity of the storm, however, casualties were low with seven-nine fatalities and 169 injuries.[44] Total damage from the storm amounted to ¥68.6 billion (US$603 million).[45] Insurance payouts amounted to ¥27.2 billion (US$241 million) in the wake of the storm.[44]

Alaska

The powerful extratropical remnants of Ma-on resulted in extensive damage along the west coast of Alaska in mid-October. Winds of 80 to 129 km/h (50 to 80 mph) battered many towns and fueled a damaging storm surge. At the Red Dog mine, a measurement of a 183 km/h (114 mph) gust was noted by the observer; however, this value was pegged as questionable and the highest verified gust was 124 km/h (77 mph). Other notable measurements include 114 km/h (71 mph) at Tin City, 110 km/h (70 mph) in Skookum Pass and Savoonga, 97 km/h (60 mph) in Golovin, and 95 km/h (59 mph) in Nome. The greatest storm surge occurred in areas without measuring capabilities, though a peak of 3.0 to 3.7 m (10 to 12 ft) was estimated in Shishmaref and 2.4 to 3.0 m (8 to 10 ft) in Kivalina. Nome itself was affected by a 3.19 m (10.45 ft) surge while Diomede and Teller had estimated values of 1.8 to 2.4 m (6 to 8 ft).[6] Record high water rises occurred at Nome and Red Dog Dock, peaking at 4.12 and 3.2 m (13.5 and 10.5 ft) respectively. The value in Nome exceeded the previous record of 3.7 m (12 ft) in October 1992; however, the measurement at Red Dog Dock was surpassed just over two months later.[46] Little precipitation accompanied the system, with only Coldfoot reporting snow accumulations of 18 cm (7 in).[6]

Nome suffered the brunt of damage from the cyclone, with most structures along the coast sustaining damage.[47] Forty-five residents had to be evacuated at the height of the storm.[6] Front Street flooded entirely and resembled a "war zone" according to residents. Most buildings in the area had their windows blown out from high winds except for those boarded with plywood. Some businesses had up to 0.91 m (3 ft) of water in their basement. Valves on three 450 kg (1,000 lb) propane tanks broke off during the storm at businesses on Front Street, prompting police to evacuate the area and the adjacent streets. Power was cut as a precautionary measure because of flammable gas.[47] Strong winds in Wales caused a 300-gallon fuel spill when a metal support at the village clinic toppled, rupturing the fuel line.[6] Large waves caused havoc across the Seward Peninsula. Erosion in Elim destroyed a local road and exposed the city's septic tanks and main water line. Shishmaref experienced some loss of sand, though recently constructed ripraps spared the area from significant damage.[47] Most affected areas had damage to power poles, with only coastal regions sustaining structural impacts. Losses throughout the state was conservatively estimated at $20 million.[6]

In the aftermath of the storm, on November 16, President George W. Bush signed a disaster declaration for the Bering Strait Regional Education Attendance Area and the Northwest Arctic Borough. Funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency was made available to residents in these areas as well as the city of Mekoryuk.[48] Public assistance teams were deployed to Nome and Unalakleet on November 19 to establish a base of operations for relief and assess the impact of the storm. Visits to smaller communities throughout the affected region were planned as well.[49] At the end of November, the disaster declaration expanded to include Chevak, the Pribilof Islands Regional Education Attendance Areas, and communities along the Lower Kuskokwim and Lower Yukon rivers.[50]

See also

- Other tropical cyclones named Ma-on

- Other tropical cyclones named Rolly

- Tropical cyclones in 2004

- Other typhoons that struck Japan during the 2004 season:

- Typhoon Nida

- Typhoon Conson

- Typhoon Dianmu

- Typhoon Chaba

- Typhoon Songda

- Typhoon Meari

- Typhoon Tokage

- 2011 Bering Sea superstorm

- Typhoon Wipha (2013) – a typhoon which hit the same areas as Ma-on

- Typhoon Phanfone (2014) – another typhoon which affected the Japanese Grand Prix

- Typhoon Hagibis (2019) – a powerful typhoon which also struck eastern Japan, disrupting both the Japanese Grand Prix and the Rugby World Cup fifteen years later

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kevin Boyle and Huang Chunliang (February 17, 2005). "Super Typhoon Ma-on". Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary: October 2004 (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g (in Japanese) "台風0422号(0422 Ma-on)" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. 2005. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Super Typhoon 26W (Ma-on) Best Track" (.TXT). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 2005. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ Gary Hufford and James Partain (2005). Climate Change and Short-Term Forecasting for Alaskan Northern Coasts (PDF) (Report). American Meteorological Society. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- Bibcode:2006AGUFM.A21A0827L. Retrieved July 15, 2014.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d e f National Weather Service Office in Fairbanks, Alaska (2005). "Alaska Event Report: High Wind". National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Katherine A. Pingree-Shippee, Norman J. Shippee, David E. Atkinson (2012). "Overview of Bering/Chukchi Sea Wave States for Selected Severe Storms" (PDF). University of Alaska Fairbanks. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Typhoon Ma-on moves north, may strike Honshu Saturday". Tokyo, Japan. Japan Economic Newswire. October 8, 2004. p. 8. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ "Strongest typhoon in decade set to strike Kanto". Tokyo, Japan. Japan Economic Newswire. October 9, 2004. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ a b Mari Murayama and Iain Wilson (October 9, 2004). "Typhoon Ma-on Reaches Central Japan; Flights Canceled (Update2)". Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c "2 dead, 6 missing as Typhoon Ma-on floods Tokyo, vicinity". Tokyo, Japan. Japan Economic Newswire. October 9, 2014. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ a b (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-936-21)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "Typhoon Ma-on lashes Tokyo". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Agence France-Presse. October 9, 2004. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ "Play suspended at Japan Open tennis". Tokyo, Japan. Associated Press. October 9, 2004. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Wataru Mashiko (2006). "High-resolution simulation of wind structure in the inner-core of Typhoon Ma-on (2004) and sensitivity experiments of horizontal resolution" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency: 1–2. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Yasou Okuda, Yukio Tamura, Hiroaki Nishimura, Hitomitsu Kikitsu, and Hisashi Okada (2005). "High Wind Damage to Buildings Caused by Typhoon in 2004" (PDF). United States–Japan Natural Resources Panel. Public Works Research Institute. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - doi:10.1029/2005GL022494.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- ^ "Precipitation Summary". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-670-15)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ a b (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-648-10)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-610-16)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-584-20)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-590-08)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-780-13)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-595-17)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ "Strongest typhoon in 10 years to hit Japan". Tokyo, Japan. Deutsche Presse-Agentur. October 9, 2004. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-624-17)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-626-11)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-629-10)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-638-08)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-636-15)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-656-17)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-662-12)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-582-26)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-575-11)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-632-23)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-651-15)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-604-24)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-741-15)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-615-24)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-777-07)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ (in Japanese) "気象災害報告 (2004-588-16)". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ a b (in Japanese) "台風200422号 (MA-ON) – 災害情報". Digital Typhoon. National Institute of Informatics. 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2006. p. 9. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Raymond S. Chapman, Sung-Chan Kim, and David J. Mark (October 2009). Storm-Induced Water Level Prediction Study for the Western Coast of Alaska (PDF) (Report). United States Army Corps of Engineers. p. 7. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Powerful Bering Sea storm hits Nome". Anchorage, Alaska. Associated Press. October 20, 2004. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ "Federal Disaster Funds Ordered For Alaska To Aid State And Local Government Storm Recovery". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Government of the United States. November 16, 2004. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Joint State/Federal Assistance Teams Deploy to Nome and Unalakleet". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Government of the United States. November 19, 2004. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Additional Alaska Communities Designated For Public Assistance". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Government of the United States. November 30, 2004. Retrieved July 15, 2014.