User:UndercoverClassicist/Alfred Biliotti

Sir Alfred Biliotti CB | |

|---|---|

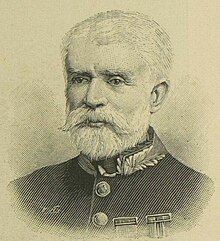

Portrayed in the Illustrated London News, 1897 | |

| Born | 14 July 1833 |

| Died | 1 February 1915 (aged 81) |

| Citizenship | British (from 1871) |

| Awards |

|

Sir Alfred Biliotti

Early life

Alfred Biliotti was born on 14 July 1833 in a

The elder Biliotti's business included work and property in the town of Makri, in the southwestern part of mainland Turkey.[3] On 7 November 1845, Lawrence Jones, a British baronet, was robbed and murdered by brigands near the town; after both the British consulate and the Ottoman government failed to find those responsible, Charles Biliotti worked with Ali Pasha, the kaymakam (district governor) of Makri, to catch them; they were arrested on 23 April 1846.[a] Following Ali Pasha's murder by relatives of the arrested men, Biliotti was forced to leave Makri and to abandon his business interests in the town; however, the affair reaffirmed the relationship between him and the British state, and he returned under British protection to Makri in March 1848 as Britain's vice-consul.[4]

Alfred Biliotti was a

Diplomatic career

In 1849, at the age of sixteen, Biliotti took a post as a clerk to his father, the British vice-consul based at Makri.[7] In 1850, he was made a dragoman (interpreter) at the British consulate on Rhodes; he is recorded from 1853 as making certified translations for the consulate from Greek into English.[6]

On 24 January 1856,[8] he became vice-consul on Rhodes. The position was unpaid,[9] as were most other British consular posts: they were generally assumed to be part-time positions whose holders would support themselves by other commercial activities.[2] From 15 February until 12 April 1860, and again from 15 February to 12 April 1861, he held the position of acting consul. He was taken on as a paid vice-consul on 26 August 1863.[10]

He became a naturalised British citizen on 23 October 1871.[11]

In 1873 or 1874, Biliotti was made vice-consul at Trebizond: the historian Lucia Patrizio Gunning has written that this move was intended to facilitate his archaeological work at the nearby site of Satala.[13] He was promoted to consul in 1879, and given additional responsibility for the consulate at Sivas in 1883.

Crete

In the midst of the strife

And war to the knife

O'er a question fierce and knotty

Let us sing to the praise

'Mid the death-strewn maze

Of Sir Alfred Biliotti

No craven was he

Who could put to sea

Saving thousands by pluck and daring

Let King George have his say

But we'll cheer the way

Of our consul's overbearing!

In 1885, he succeeded Thomas Backhouse Sandwith as Consul on Crete, based at Chania. He was made Consul-General on the island in 1890.[9] In 1900, the French diplomat and philhellene Victor Bérard alleged that Biliotti's appointment to the post in Chania had been a reward for his "obscure but useful" services in acquiring antiquities for the British Museum.[15]

The Cretan consulate was, in common with the consular delegations of most other Great Powers, marked by infighting and ineffective co-operation. During a period of unrest on Crete at the end of the 1890s, Biliotti's colleagues accused him of conspiring to assist the Cretan rebels fighting against Ottoman rule; he in turn wrote in 1896 to Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister, accusing them of undermining his diplomatic work and of being unable to work effectively together.[16]

Biliotti was credited in Punch magazine with saving "by his personal exertions many thousand Moslem lives".[17]

Later diplomatic career

In March 1899, the Foreign Office decided to transfer Biliotti to Salonica in Greece as Consul-General: a more prestigious post, albeit one that came with a salary £200 (equivalent to £23,952 in 2021) lower than he had received at Chania.[18]

Archaeological work

Objects excavated by Biliotti form part of the collections of the British Museum,[20] and at least eleven objects in the Fitzwilliam Museum of the University of Cambridge have been traced to his excavations of cemeteries on Rhodes.[21] In total, the British Museum holds more than 3,000 objects excavated by Biliotti and his collaborator Auguste Salzmann from Rhodes.[20]

During his time on Crete, Biliotti guided several British archaeologists around the island, including John Myres, who visited in the summer of 1893. He wished unsuccessfully to excavate at the site of Gortyn,[22] which was instead excavated from 1884 by what would later become the Italian School of Archaeology at Athens.[23]

Kameiros

Charles Newton first suggested the possible location of the ancient city of Kameiros during his visit to Rhodes in 1853.[9]

Biliotti and the French archaeologist Auguste Salzmann excavated at Kameiros from 1859 until 1864.[9] Their excavations included two votive deposits from the settlement's acropolis and a total of 310 graves,[24] of which 288 were burials of the archaic and classical periods in the Fikellura cemetery,[25] 18 were from the cemeteries at Paptislures and Kasviri, and 3 were from the cemetery at Kechraki.[24]

They were assisted in obtaining the necessary firman (permit) by Newton and the British Museum, to whom they sold many of their finds in exchange. The British Museum officially took charge of the excavations, engaging Biliotti and Salzmann as its agents, between October 1863 and June 1864.[9] Their finds were used by the museum to establish the chronological sequence of its ancient Greek terracotta and glass artefacts.[9]

Newton spent most of November 1863 on Rhodes, assisting with Biliotti's excavations. He was accompanied by his wife Mary and their friend Gertrude Jekyll; both women were keen artists, and Biliotti sent Turkish men to pose for them as subjects.[26]

In the British Museum's 1864 Parliamentary Report, Newton wrote that "the fruits of these excavations [at Kameiros] constitute some of the most important accessions which have been made for many years to the Department".[27]

Bargyla

Between February and September 1865, Biliotti collaborated with Salzmann to conduct excavations in the area of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, near Bodrum in southwestern Turkey.[28]. Higgs gives the beginning of the excavation as March.[29]}} These followed earlier excavations by Newton in the same area;[30] Biliotti and Salzmann worked in plots of land which Newton had initially been unable to purchase for archaeological work.[29]

During the excavations, Biliotti became the first to document a tomb at Bargylia in the shape of the mythical Scylla. Biliotti collected fragments of its architecture and sculpture for the British Museum, and wrote an account of the monument and its condition. The location of the tomb was subsequently forgotten; when it was rediscovered in 1991, Geoffrey Waywell used Biliotti's notes to help form his reconstruction of the monument.[30]

Ialysos

Biliotti excavated on Ialysos on Rhodes on behalf of the British Museum in 1868 and 1870.[9]

His excavations here uncovered the first examples of Mycenaean painted pottery known to archaeological scholarship. The objects were bought by the polymath John Ruskin, who gave them to the British Museum: they were the first large group of Mycenaean artefacts to enter its collections.[32]

Although Biliotti's notes as to the stratigraphy of their find-spots would have allowed archaeologists to realise that they dated to the Late Bronze Age (c. 1200–1100 BCE), and so belonged to a hitherto-unknown prehistoric civilisation, the artefacts were incorrectly identified as belonging to the classical period and as being "oriental" works imported to Rhodes. They therefore received comparatively little scholarly attention until after the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae in 1876, during which Schliemann named the civilisation of Bronze Age Greece as "Mycenaean": it was then realised that the Ialysos finds belonged to the same culture.[32]

Satala

During his service at Trebizond, Biliotti visited the Turkish town of Saddak for nine days in September 1874.[33] The visit was prompted by the discovery there, in 1872, of fragmentary bronze statues including a head and hand of the goddess Aphrodite.[b][36] Newton tasked Biliotti with investigating the provenance of the Aphrodite statue, which had also been claimed as a find from Thessaly; Biliotti wrote two letters back to Newton, on 22 December 1873 and 4 March 1874, affirming that it had indeed been found at Saddak. Newton subsequently sent him to Saddakto ascertain whether any additional fragments of the statue or other works were to be found there,[37] and persuaded the Foreign Office to grant Biliotti the necessary time off from his duties and money to cover his expenses during the expedition.[35]

Biliotti's explorations at Saddak were hampered by poor weather, but he reported that local peasants had found fragments of other bronze statues in the area, and correctly asserted that it was the site of the ancient town of Satala,[38] the fortress of the Roman Legio XV Apollinaris.[33] Funded by £10 (equivalent to £988 in 2021) of Newton's own money, he made small-scale excavations with a team of 36 workers in the fields where the Aphrodite statue was reported to have been found, which turned up no further sculptural remains.[39] Although Biliotti instructed the locals to alert him of any further archaeological finds, none were forthcoming, and the British Museum decided against a full excavation of the site, believing the cost to be prohibitive and the ruling Ottoman Empire likely to impose difficulties upon the export of any finds to Britain.[40]

Biliotti made a report of his excavations to Frederick Stanley, the Financial Secretary to the War Office, on 24 September, but it was not published until 1974.[41] In that year, the archeologist Terence Mitford wrote that it "remains by far the best description of the legionary fortress" at Satala, partly because the site had deteriorated considerably in the century since Biliotti's visit.[c] According to Mitford, Biliotti's work was the only recorded archaeological excavation in the Roman frontier region of Lesser Armenia, or on the limes (frontier fortifications) between Trebizond and the Keban Dam.[12]

Later career, retirement and death

Biliotti retired in 1903.[43]

He died on 1 February 1915, leaving what Barchard describes as a "relatively modest" estate of £1,107 (equivalent to £94,375 in 2021).[44] He is buried, along with other members of his family, in the Catholic cemetery on Rhodes.[45]

Biliotti was the only member of his family to take British nationality; his son and grandchildren lived in Italy, with Italian nationality.[46]

Honours

Biliotti was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1886, and a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1890.[9] He was knighted in 1896 as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, on the orders of Lord Salisbury, giving him equal rank to the British ambassador – an unusual honour for a consular official in the period.[47]

In 1882, Biliotti was elected as an honorary member of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies.[48]

Assessment, personal life and character

Biliotti's prominence seems to have been a source of bitterness for junior consular officials in Istanbul, who mocked his poor English by underlining the grammatical mistakes in his letters.[46]

Published works

- Biliotti, Alfred (10 November 1876). "The Recent Rising in Crete". The Times. p. 10.[48]

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ^ In thanks for his service, the family of Lawrence Jones presented Charles Biliotti with a silver jug and cup; Alfred Biliotti listed these as his foremost possessions in his own will.[4]

- ^ A false story later emerged that Biliotti had excavated the head and brought it to the British Museum; Biliotti did not in fact visit Satala until two years after its discovery.[34]

- survey at Satala, reaffirmed Mitford's judgement in 1998.[42]

References

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 7, 10.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 7.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Barchard 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 8. On the term "Levantine Italian", see McGuire 2020, p. 93.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 80; Barchard 2006, p. 10 (for Charles Biliotti as the Vice-Consul)

- ^ Hertslet 1865, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gill 2004, p. 80.

- ^ Hertslet 1865, p. 59.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 15; "Naturalisation Certificate: Alfred Biliotti". The National Archives. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b Mitford 1974, p. 221.

- ^ Gunning 2022, p. 226. Gill gives the year as 1873.[9]. Mitford writes that he was in post by the time of his arrival at Satala at the end of August 1874.[12]

- ^ Punch, 20 March 1897, p. 143. The author earlier noted George I's disapproval of Biliotti's 'overbearing' conduct.

- ^ Bérard 1900, pp. 92–93; Barchard 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Rathberger 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Punch, 20 March 1897', p. 143.

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Villing 2019, pp. 78–80.

- ^ a b Villing 2019, p. 72.

- ^ Gill 2023, p. 354.

- ^ Gill 2004, pp. 80–81.

- ^ de Grummond 2015, p. 418.

- ^ a b c Salmon 2019, p. 98.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 80; Salmon 2019, p. 98.

- ^ Challis 2023, p. 394.

- ^ Salmon 2019, p. 98. The "Department" mentioned is the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, of which Newton was Keeper.[24]

- ^ Gill

- ^ a b Higgs 1997, p. 30.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2006, p. 232.

- ^ "Kalathos". British Museum. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Mitford 1974, pp. 221, 225.

- ^ Lightfoot 1998, p. 275; Gunning 2022, p. 225.

- ^ a b Gunning 2022, p. 225.

- ^ Lightfoot 1998, p. 274; Gunning 2022, p. 225. Lightfoot gives the date of the sculptures' discovery as 1873, which was the year that the British Museum first learned of their excavation. The head was in the collection of the antiquities dealer Alessandro Castellani by October 1872, when he mentioned it in a letter.[35]

- ^ Gunning 2022, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Gunning 2022, p. 226.

- ^ Mitford 1974, p. 236.

- ^ Gunning 2022, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Mitford 1974, p. 225. For Stanley's position, see Matthew 2004.

- ^ Lightfoot 1998, p. 274.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 52.

- ^ "Rhodes Cemetery". Levantine Heritage. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 5, 25–26.

- ^ a b Gill 2004, p. 81.

Works cited

- Barchard, David (2006). "The Fearless and Self-reliant Servant: The Life and Career of Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833–1915), an Italian Levantine in British Service" (PDF). Studi Miceni ed Egeo-Anatolici. 48: 5–53. ISSN 1126-6651. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- OCLC 23409521.

- Challis, Debbie (2023). "The Ghosts of Ann Mary Severn Newton: Grief, an Imagined Life and (Auto)biography". In Lewis, Clare; Moshenska, Gabriel (eds.). Life-Writing in the History of Archaeology: Critical Perspectives. London: UCL Press. pp. 379–404. ISBN 9781800084506– via Google Books.

- "Consule Biliotti". Punch. Vol. 112. 20 March 1897. p. 143. Retrieved 2 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-1-134-26861-0.

- Gill, David (2004). Todd, Robert B. (ed.). The Dictionary of British Classicists. Vol. 1. Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1855069970.

- Gill, David (2023). "Archaeologists, Collectors, Curators and Donors: Reflecting on the Past Through Archaeological Lives". In Lewis, Clare; Moshenska, Gabriel (eds.). Life-Writing in the History of Archaeology: Critical Perspectives. London: UCL Press. pp. 353–378. ISBN 9781800084506– via Google Books.

- Gunning, Lucia Patrizio (2022). "Cultural Diplomacy in the Acquisition of the Head of the Satala Aphrodite for the British Museum". Journal of the History of Collections. 34 (2): 219–231. .

- Hertslet, Edward (1865). The Foreign Office List, forming a complete British Diplomatic and Consular Handbook. London: Harrison. OCLC 162820942. Retrieved 2 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- Higgs, Peter (1997). "A Newly Found Fragment of Free-Standing Sculpture from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus". In Jenkins, Ian; Waywell, Geoffrey B. (eds.). Sculptors and Sculpture of Caria and the Dodecanese. London: British Museum Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 0714122122.

- Jenkins, Ian (2006). Greek Architecture and Its Sculpture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674023888.

- Lightfoot, Christopher S. (1998). "Survey Work at Satala: A Roman Legionary Fortress in North-East Turkey". In Matthews, Roger (ed.). Ancient Anatolia: Fifty Years' Work by the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. London: British Institute at Ankara. pp. 273–284. ISBN 1898249113– via Academia.edu.

- Matthew, Henry Colin Gray (2004). "Stanley, Frederick Arthur, Sixteenth Earl of Derby". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- McGuire, Valerie (2020). Italy's Sea: Empire and Nation in the Mediterranean, 1895–1945. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781800348004.

- JSTOR 3642610.

- Rathberger, Andreas (2010). "Austria–Hungary, the Cretan Crisis, and the Ambassadors' Conference of Constantinople in 1896". In Suppan, Arnold; Graf, Maximilian (eds.). From the Austrian Empire to Communist East Central Europe. Münster: Lit Verlag. pp. 83–112. ISBN 9783643502353.

- Salmon, Nicholas (2019). "Archives and Attribution: Reconstructing the British Museum's Excavations of Kamiros". In Schierup, Stine (ed.). Documenting Ancient Rhodes: Archaeological Expeditions and Rhodian Antiquities. Gōsta Enbom Monographs. Vol. 6. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 98–112. ISBN 9788771249873– via Academia.edu.

- Villing, Alexandra (2019). "The Archaeology of Rhodes and the British Museum: Facing the Challenges of 19th-Century Excavations". In Schierup, Stine (ed.). Documenting Ancient Rhodes: Archaeological Expeditions and Rhodian Antiquities. Gōsta Enbom Monographs. Vol. 6. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 71–98. ISBN 9788771249873– via Academia.edu.

Old material

was a

Biliotti was also an accomplished archaeologist who conducted important excavations at sites in the Aegean, western Anatolia, and eastern Anatolia. He was made a Knight Commander of St. Michael and St. George in October 1898. Biliotti's despatches, though written in slightly poor English, are recognized as being of major value for 21st century scholars in fields as different as diplomatic history, anthropology, and of course archaeology.[2]

In 1897, Biliotti reported that 851

His service in Crete covered the period of the revolutionary movements of 1889, 1895 and 1897, in all of which Britain was concerned as one of the

He excavated at Cirisli Tepe (1883). Many of his finds are now displayed or stored at the British Museum.[3]

References

- ^ a b McT, Mick. "Sitia 1897".

- ^ Barchard, David. "The Fearless and Self-reliant Servant: The Life and Career of Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833–1915), An Italian Levantine in British Service" (PDF). Studi Miceni ed Egeo-Anatolici. 48: 5–53. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ British Museum Collection.