William of Tyre

William of Tyre | |

|---|---|

Roman Catholicism | |

| Occupation | Medieval chronicler, chancellor |

William of Tyre (

Following William's return to Jerusalem in 1165,

William wrote an account of the Lateran Council and a history of the Islamic states from the time of

Early life

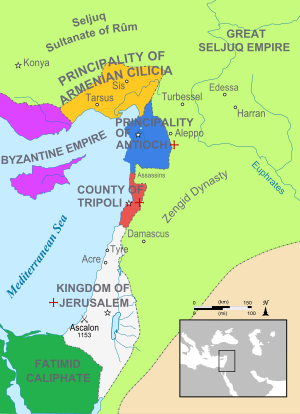

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was founded in 1099 at the end of the First Crusade. It was the third of four Christian territories to be established by the crusaders, following the County of Edessa and the Principality of Antioch, and followed by the County of Tripoli. Jerusalem's first three rulers, Godfrey of Bouillon (1099–1100), his brother Baldwin I (1100–1118), and their cousin Baldwin II (1118–1131), expanded and secured the kingdom's borders, which encompassed roughly the same territory as modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Lebanon. During the kingdom's early decades, the population was swelled by pilgrims visiting the holiest sites of Christendom. Merchants from the Mediterranean city-states of Italy and France were eager to exploit the rich trade markets of the east.[2]

William's family probably originated in either France or Italy, since he was very familiar with both countries.[3] His parents were likely merchants who had settled in the kingdom and were "apparently well-to-do",[4] although it is unknown whether they participated in the First Crusade or arrived later. William was born in Jerusalem around 1130. He had at least one brother, Ralph, who was one of the city's burgesses, a non-noble leader of the merchant community. Nothing more is known about his family, except that his mother died before 1165.[5]

As a child William was educated in Jerusalem, at the

Around 1145 William went to Europe to continue his education in the schools of France and Italy, especially in those of

Religious and political life in Jerusalem

The highest religious and political offices in Jerusalem were usually held by Europeans who had arrived on pilgrimage or crusade. William was one of the few natives with a European education, and he quickly rose through the ranks.

Amalric had come to power in 1164 and had made it his goal to

Meanwhile, William continued his advancement in the kingdom. In 1169 he visited Rome, possibly to answer accusations made against him by Archbishop Frederick, although if so, the charge is unknown. It is also possible that while Frederick was away on a diplomatic mission in Europe, a problem within the diocese forced William to seek the archbishop's assistance.[16]

On his return from Rome in 1170 he may have been commissioned by Amalric to write a history of the kingdom. He also became the tutor of Amalric's son and heir, Baldwin IV. When Baldwin was thirteen years old, he was playing with some children, who were trying to cause each other pain by scratching each other's arms. "The other boys gave evidence of pain by their outcries," wrote William, "but Baldwin, although his comrades did not spare him, endured it altogether too patiently, as if he felt nothing ... It is impossible to refrain from tears while speaking of this great misfortune."[17] William inspected Baldwin's arms and recognized the possible symptoms of leprosy, which was confirmed as Baldwin grew older.[18]

Amalric died in 1174, and Baldwin IV succeeded him as king. Nur ad-Din also died in 1174, and his general Saladin spent the rest of the decade consolidating his hold on both Egypt and Nur ad-Din's possessions in Syria, which allowed him to completely encircle Jerusalem. The subsequent events have often been interpreted as a struggle between two opposing factions, a "court party" and a "noble party." The "court party" was led by Baldwin's mother, Amalric's first wife

In 1179, William was one of the delegates from Jerusalem and the other crusader states at the

Patriarchal election of 1180

During William's absence a crisis had developed in Jerusalem. King Baldwin had reached the

The dispute affected William, since he had been appointed chancellor by Raymond and may have fallen out of favour after Raymond was removed from the regency. When Patriarch Amalric died on 6 October 1180, the two most obvious choices for his successor were William and Heraclius of Caesarea. They were fairly evenly matched in background and education, but politically they were allied with opposite parties, as Heraclius was one of Agnes of Courtenay's supporters. It seems that the canons of the Holy Sepulchre were unable to decide, and asked the king for advice; due to Agnes' influence, Heraclius was elected. There were rumours that Agnes and Heraclius were lovers, but this information comes from the partisan 13th-century continuations of the Historia, and there is no other evidence to substantiate such a claim. William himself says almost nothing about the election and Heraclius' character or his subsequent patriarchate, probably reflecting his disappointment at the outcome.[27]

Death

William remained archbishop of Tyre and chancellor of the kingdom, but the details of his life at this time are obscure. The 13th-century continuators claim that Heraclius excommunicated William in 1183, but it is unknown why Heraclius would have done this. They also claim that William went to Rome to appeal to the Pope, where Heraclius had him poisoned. According to {{Q{11815922}} and John Rowe, the obscurity of William's life during these years shows that he did not play a large political role, but concentrated on ecclesiastical affairs and the writing of his history. The story of his excommunication, and the unlikely detail that he was poisoned, were probably an invention of the Old French continuators.[28] William remained in the kingdom and continued to write up until 1184, but by then Jerusalem was internally divided by political factions and externally surrounded by the forces of Saladin, and "the only subjects that present themselves are the disasters of a sorrowing country and its manifold misfortunes, themes which can serve only to draw forth lamentations and tears."[29]

His importance had dwindled with the victory of Agnes and her supporters, and with the accession of

William's foresight about the misfortunes of his country was proven correct less than a year later. Saladin defeated King Guy at the

Works

Historia

Latin chronicle

In the present work we seem to have fallen into manifold dangers and perplexities. For, as the series of events seemed to require, we have included in this study on which we are now engaged many details about the characters, lives, and personal traits of kings, regardless of whether these facts were commendable or open to criticism. Possibly descendants of these monarchs, while perusing this work, may find this treatment difficult to brook and be angry with the chronicler beyond his just deserts. They will regard him as either mendacious or jealous—both of which charges, as God lives, we have endeavored to avoid as we would a pestilence.[35]

— William of Tyre, prologue to the Historia

William's great work is a Latin chronicle, written between 1170 and 1184.

August C. Krey thought William's Arabic sources may have come from the library of the Damascene diplomat Usama ibn Munqidh, whose library was looted by Baldwin III from a shipwreck in 1154.[38] Alan V. Murray, however, has argued that, at least for the accounts of Persia and the Turks in his chronicle, William relied on Biblical and earlier medieval legends rather than actual history, and his knowledge "may be less indicative of eastern ethnography than of western mythography."[39] William had access to the chronicles of the First Crusade, including Fulcher of Chartres, Albert of Aix, Raymond of Aguilers, Baldric of Dol, and the Gesta Francorum, as well as other documents located in the kingdom's archives. He used Walter the Chancellor and other now-lost works for the history of the Principality of Antioch. From the end of Fulcher's chronicle in 1127, William is the only source of information from an author living in Jerusalem. For events that happened in William's own lifetime, he interviewed older people who had witnessed the events about which he was writing, and drew on his own memory.[40]

William's classical education allowed him to compose Latin superior to that of many medieval writers. He used numerous ancient Roman and early Christian authors, either for quotations or as inspiration for the framework and organization of the Historia.[41] His vocabulary is almost entirely classical, with only a few medieval constructions such as "loricator" (someone who makes armour, a calque of the Arabic "zarra") and "assellare" (to empty one's bowels).[42] He was capable of clever word-play and advanced rhetorical devices, but he was prone to repetition of a number of words and phrases. His writing also shows phrasing and spelling which is unusual or unknown in purely classical Latin but not uncommon in medieval Latin, such as:

- confusion between possessive pronouns;

- confusion over the use of the prepositionin;

- collapsed diphthongs (i.e. the Latin diphthongs ae and oe are spelled simply e);

- the dative "mihi" ("to me") is spelled "michi";

- a single "s" is often doubled, for example in the adjectival place-name ending which he often spells "-enssis"; this spelling is also used to represent the Arabic "sh", a sound which Latin lacks, for example in the name Shawar which he spells "Ssauar".[43]

Literary themes and biases

Despite his quotations from Christian authors and from the Bible, William did not place much emphasis on the intervention of God in human affairs, resulting in a somewhat "secular" history.[44] Nevertheless, he included much information that is clearly legendary, especially when referring to the First Crusade, which even in his own day was already considered an age of great Christian heroes. Expanding on the accounts of Albert of Aix, Peter the Hermit is given prominence in the preaching of the First Crusade, to the point that it was he, not Pope Urban II, who originally conceived the crusade.[45] Godfrey of Bouillon, the first ruler of crusader Jerusalem, was also depicted as the leader of the crusade from the beginning, and William attributed to him legendary strength and virtue. This reflected the almost mythological status that Godfrey and the other first crusaders held for the inhabitants of Jerusalem in the late twelfth century.[46]

William gave a more nuanced picture of the kings of his own day. He claimed to have been commissioned to write by King Amalric himself, but William did not allow himself to praise the king excessively; for example, Amalric did not respect the rights of the church, and although he was a good military commander, he could not stop the increasing threat from the neighbouring Muslim states. On a personal level, William admired the king's education and his interest in history and law, but also noted that Amalric had "breasts like those of a woman hanging down to his waist"

About Amalric's son Baldwin IV, however, "there was no ambiguity".[49] Baldwin was nothing but heroic in the face of his debilitating leprosy, and he led military campaigns against Saladin even while still underaged; William tends to gloss over campaigns where Baldwin was not actually in charge, preferring to direct his praise towards the afflicted king rather than subordinate commanders.[50] William's history can be seen as an apologia, a literary defense, for the kingdom, and more specifically for Baldwin's rule. By the 1170s and 1180s, western Europeans were reluctant to support the kingdom, partly because it was far away and there were more pressing concerns in Europe, but also because leprosy was usually considered divine punishment.[51]

William was famously biased against the

Compared to other Latin authors of the twelfth century, William is surprisingly favourable to the Byzantine Empire. He had visited the Byzantine court as an official ambassador and probably knew more about Byzantine affairs than any other Latin chronicler. He shared the poor opinion of

As a medieval Christian author William could hardly avoid hostility towards the kingdom's Muslim neighbours, but as an educated man who lived among Muslims in the east, he was rarely polemical or completely dismissive of Islam. He did not think Muslims were pagans, but rather that they belonged to a heretical sect of Christianity and followed the teachings of a false prophet.[57] He often praised the Muslim leaders of his own day, even if he lamented their power over the Christian kingdom; thus Muslim rulers such as Mu'in ad-Din Unur, Nur ad-Din, Shirkuh, and even Jerusalem's ultimate conqueror Saladin are presented as honourable and pious men, characteristics that William did not bestow on many of his own Christian contemporaries.[58]

Circulation of the chronicle

After William's death the Historia was copied and circulated in the

It is unknown what title William himself gave his chronicle, although one group of manuscripts uses Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum and another uses Historia Ierosolimitana.

Old French translation

A translation of the Historia into

Other works

William reports that he wrote an account of the Third Council of the Lateran, which does not survive. He also wrote a history of the Holy Land from the time of Muhammad up to 1184, for which he used Eutychius of Alexandria as his main source. This work seems to have been known in Europe in the 13th century but it also does not survive.[67]

Modern assessment

William's neutrality as an historian was often taken for granted until the late twentieth century. August C. Krey, for example, believed that "his impartiality ... is scarcely less impressive than his critical skill."[68] Despite this excellent reputation, D. W. T. C. Vessey has shown that William was certainly not an impartial observer, especially when dealing with the events of the 1170s and 1180s. Vessey believes that William's claim to have been commissioned by Amalric is a typical ancient and medieval topos, or literary theme, in which a wise ruler, a lover of history and literature, wishes to preserve for posterity the grand deeds of his reign.[69] William's claims of impartiality are also a typical topos in ancient and medieval historical writing.[70]

His depiction of Baldwin IV as a hero is an attempt "to vindicate the politics of his own party and to blacken those of its opponents."[71] As mentioned above, William was opposed to Baldwin's mother Agnes of Courtenay, Patriarch Heraclius, and their supporters; his interpretation of events during Baldwin's reign was previously taken as fact almost without question. In the mid twentieth century, Marshall W. Baldwin,[72] Steven Runciman,[73] and Hans Eberhard Mayer[74] were influential in perpetuating this point of view, although the more recent re-evaluations of this period by Vessey, Peter Edbury and Bernard Hamilton have undone much of William's influence.[citation needed]

An often-noted flaw in the Historia is William's poor memory for dates. "Chronology is sometimes confused, and dates are given wrongly", even for basic information such as the regnal dates of the kings of Jerusalem.[75] For example, William gives the date of Amalric's death as 11 July 1173, when it actually occurred in 1174.[76]

Despite his biases and errors, William "has always been considered one of the greatest medieval writers."[77] Runciman wrote that "he had a broad vision; he understood the significance of the great events of his time and the sequence of cause and effect in history."[78] Christopher Tyerman calls him "the historian's historian",[79] and "the greatest crusade historian of all,"[80] and Bernard Hamilton says he "is justly considered one of the finest historians of the Middle Ages".[81] As the Dictionary of the Middle Ages says, "William's achievements in assembling and evaluating sources, and in writing in excellent and original Latin a critical and judicious (if chronologically faulty) narrative, make him an outstanding historian, superior by medieval, and not inferior by modern, standards of scholarship."[82]

References

- ^ In his history, William of Tyre writes, "in the fourth year after Tyre had been [captured] (that is, in 1127/28), the king, patriarch, and other leading men elected (as archbishop of Tyre) William, the venerable prior of the church of the Sepulchre of the Lord", adding that this William was "an Englishman by birth, and a man of most exemplary life and character". A few chapters later, William reports that when the Patriarch Stephen died (in 1130), "he was succeeded by William, prior of the church of the Sepulchre of the Lord…He was Flemish by birth, a native of Mesines." Two Williams were prior of the Holy Sepulchre at an early time then, with William of Mesines (Flanders) probably directly succeeding William the Englishman as Prior of the Holy Sepulchre. This also means that William of Mesines could only have been prior from 1127 (the year of the election of William the Englishman to the archbishopric of Tyre) to 1130, the year of his own election as Patriarch. See William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea", Vol. 1, trans. Emily Babcock and A.C. Krey, Bk. XIII, Ch. 23 and Bk. XIII, Ch. 26.

- ^ The most up-to-date works about the First Crusade are Thomas Asbridge, The First Crusade: A New History (Oxford: 2004) and Christopher Tyerman, God's War: A New History of the Crusades (Penguin: 2006).

- ^ Emily Atwater Babcock and August C. Krey, trans., introduction to William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea (Columbia University Press, 1943), vol. 1, p. 7.

- ^ R. B. C. Huygens, "Editing William of Tyre", Sacris Erudiri 27 (1984), p. 462.

- ^ Peter W. Edbury and John G. Rowe, William of Tyre: Historian of the Latin East (Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 14.

- cardinal priest of SS. Silvestri e Martino, and supported Antipope Victor IV over Pope Alexander III.

- ^ R. B. C. Huygens, ed., introduction to Willemi Tyrensis Archiepiscopi Chronicon, Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Medievalis, vol. 38 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1986), p. 2.

- ^ G. A. Loud and J. W. Cox, "The 'Lost' Autobiographical Chapter of William of Tyre's Chronicle (Book XIX.12)", The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, ed. Alan V. Murray (ABC-Clio, 2006), vol. 4, Appendix: Texts and Documents #4, p. 1306.

- ^ Jacques Verger, "The birth of the universities". A History of the University in Europe, vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, ed. Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 47–50.

- ^ Charles Homer Haskins, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century (Harvard University Press, 1927; repr. Meridian Books, 1966), p. 103.

- ^ The chapter of the Historia detailing his education in Europe was lost until Robert Huygens discovered it 1961, in a manuscript in the Vatican Library (ms. Vaticanus latinus 2002); Huygens, "Guillaume de Tyr étudiant: un chapître (XIX, 12) de son Histoire retrouvé" (Latomus 21, 1962), p. 813. It is unknown why no other manuscript has this chapter, but Huygens suggests an early copyist considered it out of place within the rest of book nineteen and excised it, and thus all subsequent copies also lacked it (ibid., p. 820). It was included in Huygen's critical edition of the Historia (book 19, chapter 12, pp. 879–881.) As the chapter had not yet been discovered, it is not included in the 1943 English translation by Babcock and Krey.

- ^ Loud and Cox, p. 1306. Loud and Cox also give an English translation of the chapter. It has also been translated online by Paul R. Hyams, "William of Tyre's Education, 1145/65 Archived 27 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ Alan V. Murray, "William of Tyre". The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, vol. 4, p. 1281.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Hans E. Mayer, The Crusades, 2nd ed., trans. John Gillingham (Oxford: 1988), pp. 119–120.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 16–17.

- ^ William of Tyre, trans. Babcock and Krey, vol. 2, book 21, chapter 1, p. 398.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 17; Bernard Hamilton, The Leper King and His Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Peter W. Edbury, "Propaganda and faction in the Kingdom of Jerusalem: the background to Hattin", Crusaders and Moslems in Twelfth-Century Syria (ed. Maya Shatzmiller, Leiden: Brill, 1993), p. 174.

- ^ Hamilton p. 158.

- ^ Hamilton, p. 93.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Hamilton, p. 144.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 54–55, 146–47; Hamilton, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Hamilton, pp. 150–158.

- ^ Hamilton, pp. 162–163; Edbury and Rowe, "William of Tyre and the Patriarchal election of 1180", The English Historical Review 93 (1978), repr. Kingdoms of the Crusaders: From Jerusalem to Cyprus (Aldershot: Ashgate, Variorum Collected Series Studies, 1999), pp. 23–25.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 20–22.

- ^ William of Tyre, trans. Babcock and Krey, vol. 2, book 23, preface, p. 505.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 22.

- ^ Hans Mayer, "Zum Tod Wilhelms von Tyrus" (Archiv für Diplomatik 5/6, 1959–1960; repr. Kreuzzüge und lateinischer Osten (Aldershot: Ashgate, Variorum Collected Studies Series, 1983)), p. 201. Huygens (Chronicon, introduction, p. 1), Susan M. Babbitt, "William of Tyre", Dictionary of the Middle Ages (ed. Joseph Strayer, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1989), vol. 12, p. 643), Helen J. Nicholson ("William of Tyre", Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, ed. Kelly Boyd (Taylor & Francis, 1999), vol. 2, p. 1301), and Alan V. Murray ("William of Tyre", The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, vol. 4, p. 1281), among others, accept Mayer's date.

- ^ Hamilton, pp. 229–232.

- J. A. Giles(London, 1849), vol. II, p. 63.

- ^ Babcock and Krey, introduction, p. 25, n. 24.

- ^ William of Tyre, trans. Babcock and Krey, vol. 1, prologue, p. 54.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 26.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 28–31.

- ^ Babcock and Krey, introduction, p. 16.

- ^ Alan V. Murray, "William of Tyre and the origin of the Turks: on the sources of the Gesta Orientalium Principum," in Dei gesta Per Francos: Études sur les crioisades dédiées à Jean Richard/Crusade Studies in Honour of Jean Richard, edd. Michel Balard, Benjamin Z. Kedar and Jonathan Riley-Smith (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), pp. 228–229.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Huygens, Chronicon, introduction, pp. 41–42. William himself translates the Arabic "zarra"; William of Tyre, trans. Babcock and Krey, vol. 1, book 5, chapter 11, p. 241.

- ^ Huygens, Chronicon, introduction, pp. 40–47. Huygens continues with a lengthy discussion of William's style and language.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Frederic Duncalf, "The First Crusade: Clermont to Constantinople", A History of the Crusades (gen. ed. Kenneth M. Setton), vol. 1: The First Hundred Years (ed. Marshall W. Baldwin, University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), p. 258.

- ^ John Carl Andressohn, The Ancestry and Life of Godfrey of Bouillon (Indiana University Publications, Social Science Series 5, 1947), p. 5.

- ^ William of Tyre, trans. Babcock and Krey, vol. 2, book 19, chapter 3, p. 300.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 76.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 78.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 65.

- ^ Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars (Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 11.

- ^ Barber, p. 12.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 132–34.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 137–141.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 141–150.

- ^ R. C. Schwinges, "William of Tyre, the Muslim enemy, and the problem of tolerance." Tolerance and Intolerance: Social Conflict in the Age of the Crusades, ed. Michael Gervers and James M. Powell (Syracuse University Press, 2001), pp. 126–27.

- ^ Schwinges, p. 128.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Helen J. Nicholson, ed., The Chronicle of the Third Crusade: The Itinerarium Peregrinorum and the Gesta Regis Ricardi (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997), introduction, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Huygens, Chronicon, introduction, pp. 32–34.

- Magdalene CollegeF.4.22 ("W") have an English provenance. The aforementioned Vatican lat. 2002 ("V") and a related fragment ("Fr") were also used. Two manuscripts, Bibliothèque nationale lat. 17153 ("L") and Vatican Reginensis lat. 690 ("R") were not used in Huygens' edition. Huygens, Chronicon, introduction, pp. 3–31.

- ^ Babcock and Krey, introduction, p. 44.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 4; For a more updated and detailed historiographical analysis

- ^ González Cristina, La tercera crónica de Alfonso X: "La Gran Conquista de Ultramar", 1992.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Babcock and Krey, introduction, p. 32.

- ^ D. W. T. C. Vessey, "William of Tyre and the art of historiography." Mediaeval Studies 35 (1973), pp. 437–38.

- ^ Vessey, p. 446.

- ^ Vessey, p. 446.

- ^ Marshall W. Baldwin, "The Decline and Fall of Jerusalem, 1174–1189", A History of the Crusades, vol. 1, p. 592ff.

- ^ Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, vol. 2: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East (Cambridge University Press, 1952), p. 404.

- ^ Mayer, The Crusades, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Edbury and Rowe, 1988, p. 26.

- ^ William of Tyre, trans. Babcock and Krey, vol. 2, book 20, ch. 31, p. 395.

- ^ "Depuis toujours, Guillaume de Tyr a été considéré comme l'un des meilleurs écrivains du moyen âge." Huygens, Chronicon, introduction, p. 39.

- ^ Runciman, A History of the Crusades, vol. 2, p. 477.

- ^ Tyerman, God's War, p. 361.

- ^ Christopher Tyerman, The Invention of the Crusades (University of Toronto Press, 1998), p. 126.

- ^ Hamilton, p. 6.

- ^ Babbitt, p. 643.

Sources

Primary

- William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, trans. E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey. Columbia University Press, 1943.

Secondary

- John Carl Andressohn, The Ancestry and Life of Godfrey of Bouillon. Indiana University Publications, Social Science Series 5, 1947.

- Susan M. Babbitt, "William of Tyre." Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ed. Joseph Strayer. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1989, vol. 12.

- Marshall W. Baldwin, "The Decline and Fall of Jerusalem, 1174–1189." A History of the Crusades (gen. ed. Kenneth M. Setton), vol. 1: The First Hundred Years (ed. Marshall W. Baldwin). University of Wisconsin Press, 1969.

- Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Frederic Duncalf, "The First Crusade: Clermont to Constantinople." A History of the Crusades (gen. ed. Kenneth M. Setton), vol. 1: The First Hundred Years (ed. Marshall W. Baldwin). University of Wisconsin Press, 1969.

- Peter W. Edbury and John G. Rowe, "William of Tyre and the Patriarchal election of 1180." The English Historical Review 93 (1978), repr. Kingdoms of the Crusaders: From Jerusalem to Cyprus (Aldershot: Ashgate, Variorum Collected Series Studies, 1999), pp. 1–25.

- Peter W. Edbury and John G. Rowe, William of Tyre: Historian of the Latin East. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Peter W. Edbury, "Propaganda and faction in the Kingdom of Jerusalem: the background to Hattin." Crusaders and Muslims in Twelfth-Century Syria, ed. Maya Shatzmiller (Leiden: Brill, 1993), repr. in Kingdoms of the Crusaders: From Jerusalem to Cyprus (Aldershot: Ashgate, Variorum Collected Series Studies, 1999), pp. 173–189.

- Bernard Hamilton, The Leper King and his Heirs. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Charles Homer Haskins, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Harvard University Press, 1927; repr. Meridian Books, 1966.

- R. B. C. Huygens, "Guillaume de Tyr étudiant: un chapître (XIX, 12) de son Histoire retrouvé." Latomus 21 (1962), pp. 811–829. (in French)

- R. B. C. Huygens, "Editing William of Tyre." Sacris Erudiri 27 (1984), pp. 461–473.

- G. A. Loud and J. W. Cox, "The 'Lost' Autobiographical Chapter of William of Tyre's Chronicle (Book XIX.12)." The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, ed. Alan V. Murray (ABC-Clio, 2006), vol. 4, Appendix: Texts and Documents #4, pp. 1305–1308.

- Hans E. Mayer, The Crusades, 2nd ed., trans. John Gillingham. Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Alan V. Murray, "William of Tyre and the origin of the Turks: on the sources of the Gesta Orientalium Principum," in Dei gesta Per Francos: Études sur les crioisades dédiées à Jean Richard/Crusade Studies in Honour of Jean Richard, edd. Michel Balard, Benjamin Z. Kedar and Jonathan Riley-Smith (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), pp. 217–229.

- Alan V. Murray, "William of Tyre." The Crusades: An Encyclopedia, ed. Alan V. Murray (ABC-Clio, 2006), vol. 4.

- Helen J. Nicholson, "William of Tyre." Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing, ed. Kelly Boyd. Taylor & Francis, 1999, vol. 2.

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, volume 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press, 1951.

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, volume 2: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East. Cambridge University Press, 1952.

- R. C. Schwinges, "William of Tyre, the Muslim enemy, and the problem of tolerance." Tolerance and Intolerance. Social Conflict in the Age of the Crusades, ed. Michael Gervers and James M. Powell, Syracuse University Press, 2001.

- Christopher Tyerman, The Invention of the Crusades. University of Toronto Press, 1998.

- Christopher Tyerman, God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Penguin, 2006.

- Jacques Verger, "The birth of the universities". A History of the University in Europe, vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, ed. Hilde de Ridder-Symoens. Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 47–55.

- D. W. T. C. Vessey, "William of Tyre and the art of historiography." Mediaeval Studies 35 (1973), pp. 433–455.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Willemi Tyrensis Archiepiscopi Chronicon, ed. R. B. C. Huygens. 2 vols. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Medievalis, vols. 63 & 63a. Turnholt: Brepols, 1986. Latin text with introduction and notes in French.

- L'Estoire d'Eracles empereur et la conqueste de la terre d'Outremer, in Recueil des historiens des croisades, Historiens occidentaux, vols. I–II (1844, 1859). (in French)

- J. A. Giles, trans. Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History. London, 1849.

- La Chronique d'Ernoul et de Bernard le Trésorier, ed. Louis de Mas Latrie. Paris, 1871. (in French)

- Guillaume de Tyr et ses continuateurs, ed. Alexis Paulin Paris. Paris, 1879–1880. (in French)

- Margaret Ruth Morgan, La continuation de Guillaume de Tyr (1184–1197). Paris, 1982. (in French)

- Helen J. Nicholson, ed. The Chronicle of the Third Crusade: The Itinerarium Peregrinorum and the Gesta Regis Ricardi. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997.

- Janet Shirley, Crusader Syria in the Thirteenth Century: The Rothelin Continuation of the History of William of Tyre with part of the Eracles or Acre text. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999.

Secondary sources

- Thomas Asbridge, The First Crusade: A New History. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 677.

- R. H. C. Davis, "William of Tyre." Relations Between East and West in the Middle Ages, ed. Derek Baker (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1973), pp. 64–76.

- Peter W. Edbury, "The French translation of William of Tyre's Historia: the manuscript tradition." Crusades 6 (2007).

- Bernard Hamilton, "William of Tyre and the Byzantine Empire." Porphyrogenita: Essays on the History and Literature of Byzantium and the Latin East in Honour of Julian Chrysostomides, eds. Charalambos Dendrinos, Jonathan Harris, Eirene Harvalia-Crook, and Judith Herrin (Ashgate, 2003).

- Philip Handyside, The Old French William of Tyre. Brill, 2015.

- Rudolf Hiestand, "Zum Leben und Laufbahn Wilhelms von Tyrus." Deutsches Archiv 34 (1978), pp. 345–380. (in German)

- Conor Kostick, "William of Tyre, Livy and the Vocabulary of Class." Journal of the History of Ideas 65.3 (2004), 352–367.

- Hans E. Mayer, "Guillaume de Tyr à l'école." Mémoires de l'Académie des sciences, arts et belles-lettres de Dijon 117 (1985–86), repr. Kings and Lords in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Aldershot: Ashgate, Variorum Collected Studies Series, 1994), pp. 257–265. (in French)

- Hans E. Mayer, "Zum Tode Wilhelms von Tyrus." Archiv für Diplomatik 5–6 (1959–1960), pp. 182–201. (in German)

- Margaret Ruth Morgan, The Chronicle of Ernoul and the Continuations of William of Tyre. Oxford University Press, 1973.

- Hans Prutz, "Studien über Wilhelm von Tyrus." Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für ältere deutsche Geschichtskunde 8 (1883), pp. 91–132. (in German)

External links

- Excerpts from the Historia from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Fiasco at Damascus 1148 from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Latin version from the The Latin Library(in Latin)

- Latin version from Crusades-Encyclopedia.com (in Latin)

- Latin version with concordance from Intertext.com (in Latin)

- Old French translation and continuation from Internet Medieval Sourcebook(in French)

- English translation by E.A. Babcock and A.C. Krey, from ACLS Humanities E-Books (login required)