Medieval university

A medieval university was a

The word universitas originally applied only to the scholastic guilds—that is, the corporation of students and masters—within the studium, and it was always modified, as universitas magistrorum, universitas scholarium, or universitas magistrorum et scholarium. Eventually, probably in the late 14th century, the term began to appear by itself to exclusively mean a self-regulating community of teachers and scholars recognized and sanctioned by civil or ecclesiastical authority.[5]

From the

Antecedents

The

With the increasing growth and urbanization of European society during the 12th and 13th centuries, a demand grew for

S. F. Alatas has noted some parallels between

Establishment

Hastings Rashdall set out the modern understanding[16] of the medieval origins of European universities, noting that the earliest universities emerged spontaneously as "a scholastic Guild, whether of Masters or Students... without any express authorization of King, Pope, Prince or Prelate".[17]

Among the earliest universities of this type were the

In many cases universities petitioned secular power for privileges and this became a model. The

The University of Paris was formally recognized when Pope Gregory IX issued the bull Parens scientiarum (1231).[20] This was a revolutionary step: studium generale (university) and universitas (corporation of students or teachers) existed even before, but after the issuing of the bull, they attained autonomy. "[T]he papal bull of 1233, which stipulated that anyone admitted as a teacher in Toulouse had the right to teach everywhere without further examinations (ius ubique docendi), in time, transformed this privilege into the single most important defining characteristic of the university and made it the symbol of its institutional autonomy .... By the year 1292, even the two oldest universities, Bologna and Paris, felt the need to seek similar bulls from Pope Nicholas IV".[20]

By the 13th century, almost half of the highest offices in the Church were occupied by degree masters (

The development of the medieval university coincided with the widespread reintroduction of Aristotle from Byzantine and Arab scholars. In fact, the European university put Aristotelian and other natural science texts at the center of its curriculum,[22] with the result that the "medieval university laid far greater emphasis on science than does its modern counterpart and descendent".[23]

Although it has been assumed that the universities went into decline during the

Characteristics

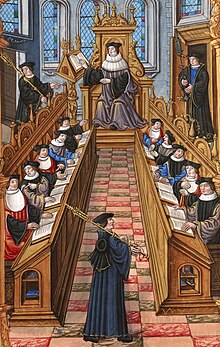

Initially medieval universities did not have physical facilities such as the campus of a modern university. Classes were taught wherever space was available, such as churches and homes. A university was not a physical space but a collection of individuals banded together as a universitas. Soon, however, universities began to rent, buy or construct buildings specifically for the purposes of teaching.[25]

Universities were generally structured along three types, depending on who paid the teachers. The first type was in

It was also characteristic of teachers and scholars to move around. Universities often competed to secure the best and most popular teachers, leading to the marketisation of teaching. Universities published their list of scholars to entice students to study at their institution. Students of Peter Abelard followed him to Melun, Corbeil, and Paris,[26] showing that popular teachers brought students with them.

Students

Students attended the medieval university at different ages—from 14 if they were attending Oxford or Paris to study the arts, to their 30s if they were studying law in Bologna. During this period of study, students often lived far from home and unsupervised, and as such developed a reputation, both among contemporary commentators and modern historians, for drunken debauchery. Students are frequently criticized in the Middle Ages for neglecting their studies for drinking, gambling and sleeping with prostitutes.[27] In Bologna, some of their laws permitted students to be citizens of the city if they were enrolled at a university.[28][page needed]

Course of study

University studies took six years for a

Much of medieval thought in philosophy and theology can be found in

Once a Master of Arts degree had been conferred, the student could leave the university or pursue further studies in one of the higher faculties, law, medicine, or theology, the last one being the most prestigious. Originally, only few universities had a faculty of theology, because the popes wanted to control the theological studies. Until the mid-14th century, theology could be studied only at universities in Paris, Oxford, Cambridge and Rome. First the establishment of the University of Prague (1347) ended their monopoly and afterwards also other universities got the right to establish theological faculties.[36]

A popular textbook for theological study was called the Sentences (Quattuor libri sententiarum) of Peter Lombard; theology students as well as masters were required to lecture or to write extensive commentaries on this text as part of their curriculum.[37][38] Studies in the higher faculties could take up to twelve years for a master's degree or doctorate (initially the two were synonymous), though again a bachelor's and a licentiate's degree could be awarded along the way.[39][page needed]

Courses were offered according to books, not by subject or theme. For example, a course might be on a book by Aristotle, or a book from the Bible. Courses were not elective: the course offerings were set, and everyone had to take the same courses. There were, however, occasional choices as to which teacher to use.[40]

Students often entered the university at fourteen to fifteen years of age, though many were older.[41] Classes usually started at 5:00 or 6:00 a.m.

Legal status

As students had the legal status of clerics,

This led to uneasy tensions with secular authorities—the demarcation between

Most universities in Europe were recognized by the Holy See as studia generalia, testified by a papal bull. Members of these institutions were encouraged to disseminate their knowledge across Europe, often lecturing at a different studium generale. Indeed, one of the privileges the papal bull confirmed was the right to confer the ius ubique docendi, an entitlement to teach everywhere.[43]

See also

- Ancient higher-learning institutions

- Ancient universities in the UK

- Ancient universities of Scotland

- List of oldest universities in continuous operation

- Nation (university)

- Renaissance of the 12th century

References

- ^ de Ridder-Symoens (1992), pp. 47–55

- ^ ISBN 0-87249-376-8.

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ Verger, Jacques. "The Universities and Scholasticism," in The New Cambridge Medieval History. Volume V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007. p. 257.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: History of Education. The development of the universities.

- ISBN 3-406-36956-1

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2.

- ^ Verger 1999

- ^ Oestreich, Thomas (1913). "Pope St. Gregory VII". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

- (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2017.

- JSTOR 1595223.

Thus the university, as a form of social organization, was peculiar to medieval Europe. Later, it was exported to all parts of the world, including the Muslim East; and it has remained with us down to the present day. But back in the middle ages, outside of Europe, there was nothing anything quite like it anywhere.

- ^ The scholarship on these differences is summarized in Huff, Toby. Rise of Early Modern Science (2nd ed.). pp. 149–159, pp. 179–189.

- JSTOR 601679.

- ISBN 88-02-03568-7.

- ISBN 978-8880828419.

- ISSN 0926-6070.

In his magisterial work on European universities, Hastings Rashdall [considered that] the integrity of a university is preserved only when the institution evolved into an internally regulated corporation of scholars, be they students or masters.

- Clarendon Press. pp. 17–18. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

The University was originally a scholastic Guild, whether of Masters or Students. Such Guilds sprang into existence, like other Guilds, without any express authorisation of King, Pope, Prince, or Prelate. They were spontaneous products of the instinct of association that swept over the towns of Europe in the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

- ^ "10 of the Oldest Universities in the World". Top Universities. 16 September 2016. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ Seelinger, Lani. "The 13 Oldest Universities In The World". Culture Trip. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Kemal Gürüz, Quality Assurance in a Globalized Higher Education Environment: An Historical Perspective Archived 2008-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, Istanbul, 2007, p. 5

- ISSN 0926-6070.

- ^ Toby Huff, Rise of early modern science 2nd ed. p. 180-181

- ^ Edward Grant, "Science in the Medieval University", in James M. Kittleson and Pamela J. Transue, ed., Rebirth, Reform and Resilience: Universities in Transition, 1300-1700, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1984, p. 68

- ^ Toby Huff, Rise of Early Modern science, 2nd ed., p. 344.

- ^ A. Giesysztor, Part II, Chapter 4, page 136: University Buildings, in A History of the University In Europe, Volume I: Universities in the Middle Ages, W. Ruegg (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- ^ James M. Kittleson, Rebirth, reform and resilience: Universities in transition 1300–1700 (Columbus, Ohio State University Press, 1984), p. 164.

- ISBN 9780199670833. Archivedfrom the original on 15 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rait, Robert S. (1931) [1912]. Life in the Medieval University.

- ^ Hastings Rashdall, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, 3 volumes; Powicke, F. M., and Emden, A. B. (eds.), 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1936.[page needed]

- ^ Leff, G.; North, J.; "Chapter 10: The Faculty of Arts", in A History of the University in Europe, Volume I: Universities in the Middle Ages; Ruegg, W. (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- ^ Rait, Robert S. (1912); Life in the Medieval University, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Rait (1912), p. 138.

- ^ Gilman, Daniel Coit, et al. (1905). New International Encyclopedia. Lemma "Arts, Liberal".

- ^ Rait (1912), pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Rait (1912), p. 139.

- ISBN 3-406-36952-9.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-7864-5201-9.

- ^ Pedersen (1997).

- ^ Pedersen (1997), Chapter 10: "Curricula and intellectual trends".

- ^ Rashdall ([1895] 1987), vol. 3, p. 352.

- ^ Rashdall ([1895] 1987), vol. 3, p. 360.

- ^ Rashdall [1895] 1987, vol. 1, ch. I, p. 8.

Bibliography

- Cobban, Alan B. English University Life in the Middle Ages Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8142-0826-6

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2

- Dunphy, Graeme (2015). "The Medieval University". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). Handbook of Medieval Culture. Vol. 1. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1706–1734. ISBN 9783110267303.

- Ferruolo, Stephen: The Origins of the University: The Schools of Paris and their Critics, 1100-1215 Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8047-1266-2

- ISBN 0-87968-379-1

- Lee, John S., and Steer, Christian (eds.), Commemoration in Medieval Cambridge History of the University of Cambridge, Boydell, 2018. ISBN 9781783273348

- Pedersen, Olaf, The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ISBN 0-527-73650-3

- ISBN 0-19-821431-6

- Seybolt, Robert Francis (trans.): The Manuale Scholarium: An Original Account of Life in the Mediaeval University, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1921

- Thorndike, Lynn (trans. and ed.): University Records and Life in the Middle Ages, New York: Columbia University Press, 1975, ISBN 0-393-09216-X

- Verger, Jacques (1999). "Universität". Lexikon des Mittelalters. Vol. 8. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler. cols:1249–1255.

External links

- The Shift of Medical Education into the Universities

- The Educational Legacy of Mediaeval and Renaissance Traditions.

- From Manuscript to Print: Evolution of the Mediaeval Book.

- Life of the Students at Paris.

- Mediaeval History: A Mediaeval Atlas Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Cambridge, A Brief History: The Mediaeval University.

- Mediaeval Science, the Church, and Universities

- Quality Assurance In A Globalized Higher Education Environment: An Historical Perspective (DOCfile)

- The Rise of Universities (classic), Charles Homer Haskins, 1923