Arbeia

| Arbeia Roman Fort and Museum | ||

|---|---|---|

Grid reference NZ365679 | | |

Arbeia was a large

Name

"Arbeia" may mean the "fort of the

Alternatively, it could mean "(fort by a) stream noted for wild turnips".[6]

History

The fort was built in 129 AD as a small cohort fort, a few years later than most of the Hadrian's Wall forts, on the Lawe Top overlooking the mouth of the River Tyne and four miles beyond the eastern end of Hadrian’s wall, from where it guarded the flank and main sea supply route to the Wall and the small port on the south of the Tyne.[7][8]

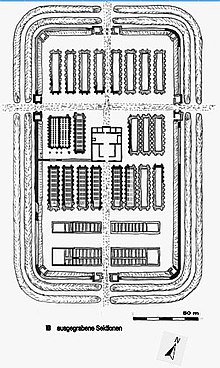

Its garrison was reduced during the occupation of Scotland in the reign of Antoninus Pius. Early in Marcus Aurelius's reign (161 to 180) it was reoccupied[9] and from 198 it was considerably altered in plan and usage. A dividing wall between the northern and southern halves of the fort allowed the north part to store supplies from sea-going ships, while the southern part remained a garrison. The modifications are associated with Septimius Severus' Roman invasion of Caledonia (208–211), a series of campaigns against the troublesome Caledonian tribes, in which the fort may have served as his headquarters.[7]

From 220-235 a new principia (headquarters) with new barracks were built in the southern part of the fort, probably to house the new garrison of Cohors V Gallorum of double size (nominally 1000 men) while the original principia were converted to a granary and 9 more granaries were built in the southern part of the fort, bringing the total to 24. It contains the only permanent stone-built granaries yet found in Britain.[10] It shows that Arbeia became the main supply base for the whole of Hadrian’s Wall rather than obtaining its supplies from the local region by purchase, taxation or requisition which was the usual assumption.

In later 3rd century occupants of the vicus appear to have moved into the empty fort.[11]

After a fire in about 300, 8 of the granaries were converted to barracks, the principia were enlarged and a new large praetorium (commanding officer’s house) built. The fort was finally abandoned around 400.

It is said to be the birthplace of the Northumbrian King Oswin.[12]

When the fort was unexpectedly discovered in 1875 by an unknown amateur it made national news as the numerous finds near the centre of a Northern industrial town were of a quality that shocked archaeologists who found it hard to believe such a site could yield these treasures. The Roman remains attracted crowds that flocked to the town and despite some believing that they were forgeries, further excavations proved that it was a sensational archaeological discovery.[13]

Garrison

The

The final garrison was the Numerus Barcariorum Tigrisiensium who were transferred from Lancaster Roman Fort[16] and originally barge-men from the River Tigris in the Middle-East recorded in the Notitia Dignitatum.

Praetorium

The later commanding officer’s house built after 300 resembled elegant 3rd and 4th century houses from the Mediterranean area and included an atrium at the entrance leading to a colonnaded courtyard with fountain around which most of the rooms were organised. Many of the rooms were decorated with frescoes. A private thermal baths suite included hypocausts for the heated rooms.

Museum

Two monuments in the museum at Arbeia testify to the cosmopolitan nature of its shifting population. One commemorate Regina, a British woman of the Catuvellauni tribe (approximately modern Hertfordshire).[17] She was first the slave, then the freedwoman and wife of Barates, an Arab merchant from Palmyra (now part of Syria) who, evidently missing her greatly, set up a gravestone after she died at the age of 30 in the second half of the second century.[18] (Barates himself is buried at the nearby fort at Corbridge in Northumberland.) The second commemorates Victor, another former slave,[19] freed by Numerianus of the Ala I Asturum, who also arranged his funeral ("piantissime": with all devotion) when Victor died at the age of 20. The stone records that Victor was "of the Moorish nation".

The museum also holds an altarpiece to a previously unknown god and a tablet with the name of the Emperor Severus Alexander (died 235) chiselled off, an example of damnatio memoriae.

Reconstruction

The West Gate of the fort was reconstructed in 1986 to give an impression of the place. The Reconstruction of the fort has been accomplished using research which was undertaken following excavations, standing where it had originally existed during the Roman occupation of Britain.

A Roman gatehouse, barracks and Commanding Officer's house have been reconstructed on their original foundations. The gatehouse holds many displays related to the history of the fort, and its upper levels provide an overview of the archaeological site.[20]

External links

References

- ^ Archaeologia Aeliana: Or, Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquities. Sarah Hodgson. 2005.

- ISBN 978-1-4456-3147-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7509-5241-5.

- ^ Bruce, John (2006). Handbook to the Roman Wall. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Society of Antiquaries.

- ^ Bowersock, Glen (1983). Roman Arabia. Harvard University Press.

- ^ ISBN 9781785211898.

- ^ "About Arbeia, South Shields Roman Fort | Arbeia South Shields Roman Fort". arbeiaromanfort.org.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Dore, J. N. and Gillam, J. Pearson. (1979) The Roman fort at South Shields Tyne & Wear: excavations 1875–1975, Soc Antiq Newcastle upon Tyne Monogr Ser, 1979 Volume:1

- ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Dore, J. N. and Gillam, J. Pearson. (1979) The Roman fort at South Shields Tyne & Wear: excavations 1875–1975, Soc Antiq Newcastle upon Tyne Monogr Ser, 1979 Volume:1

- ^ "About Arbeia, South Shields Roman Fort | Arbeia South Shields Roman Fort". arbeiaromanfort.org.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ David Kidd and Jean Stokes, The People’s Roman Remains Park, Harton Village Press ISBN 9781838310004 https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/history/how-roman-finds-south-shields-19565255

- ^ RIB 1064

- ^ South Shield (Arbeia) Roman Fort https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/places/arbeia-roman-fort/

- ^ Richmond, Ian (1953). "Excavations on the site of the Roman Fort at Lancaster, 1950" (PDF). Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 105: p 11

- ^ "Britain: Back to barracks in Roman Tyne and Wear". 23 October 2011.

- ISSN 0066-5983.

- ^ "Britain: Back to barracks in Roman Tyne and Wear". 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Arbeia Roman Fort development boosted by £150,000". BBC News. 22 January 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2020.