Bengali Brahmin

| Bengali Brahmins | |

|---|---|

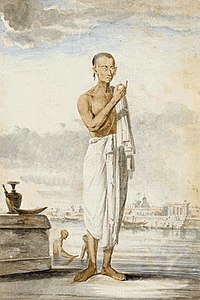

A Bengali Brahmin priest | |

| Religions | Hinduism |

| Languages | Bengali |

| Populated states | West Bengal, India |

| Related groups | Maithil Brahmin, Utkala Brahmin, Kanyakubja Brahmin |

Bengali Brahmins are the community of Hindu Brahmins, who traditionally reside in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, currently comprising the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh.

The Bengali Brahmins, along with Baidyas and Kayasthas, are regarded among the three traditional higher castes of Bengal.[1] In the colonial era, the Bhadraloks of Bengal were primarily, but not exclusively, drawn from these three castes, who continue to maintain a collective hegemony in West Bengal.[2][3][4]

History

For a long period, Bengal was not part of Vedic culture.

It is traditionally believed that much later, in the 11th century CE, after the decline of the

Referring to the linkages between class and caste in Bengal, Bandyopadhyay mentions that the Brahmins, along with the other two upper castes, refrained from physical labour but controlled land, and as such represented "the three traditional higher castes of Bengal".[1]

Clans

Apart from the common classification as Kulina, Srotriya and Vangaja, Bengali Brahmins are divided into the following clans or divisions:[17][18]

- Radhi

- Varendra

- Vaidika

- Saptasati

- Madhyasreni

- Sakadwipi

Kulin Brahmin

Kulin Brahmins trace their ancestry to five families of

These Brahmins were designated as Kulina ("superior") in order to differentiate them from the more established local Brahmins.

Post Partition of India

When the British left India in 1947,

Notable people

- Ganesha dynastyof Bengal

- Raja Krishnachandra Roy, Raja of Nadia Raj

- Bhurishrestha[26]

- Bhavashankari, Queen of Bhurishrestha[27]

- Mamata Banerjee (1955–present), 8th and present Chief Minister of West Bengal

- Surendranath Banerjee (1848–1925), founder of the Indian National Association, first Indian to pass the Indian civil service examination[28]

- Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838–1894), Indian Bengali novelist, poet and journalist [29]

- Ashok Kumar (Ganguly) (1911–2001), Indian film actor[30]

- Kishore Kumar (Ganguly) (1929–1987), Indian playback singer, actor, music director, lyricist, writer, director, producer and screenwriter[30]

- Pranab Mukherjee (1935–2020), 13th President of India and a veteran leader of the Indian National Congress[31]

- Dwarkanath Tagore (1794–1846), one of the first Indian industrialists to form an enterprise with British partners[32]

See also

Notes

- ^ ISBN 81-7829-316-1.

- ISBN 978-0-761-99849-5.

- JSTOR 44508277.

- ISBN 9789384082994.

- ISBN 978-0-19-534713-5.

- ^ a b Niyogi, Puspa (1967). Brahmanic Settlements in Different Subdivisions of Ancient Bengal. Indian Studies: Past & Present. pp. 19, 37–38.

- ^ a b SIRCAR, D. C. (1959). STUDIES IN THE SOCIETY AND ADMINISTRATION OF ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL INDIA VOL. 1. FIRMA K. L. MUKHOPADHYAY, CALCUTTA. pp. 1–4, 18–19.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8364-0633-7.

- ^ a b Griffiths, Arlo (2018). "Four More Gupta-period Copperplate Grants from Bengal". Pratna Samiksha: A Journal of Archaeology. New Series (9): 15–57.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-86311-378-9.

- ^ Ghosh, Suniti Kumar (2002). The Tragic Partition of Bengal. Indian Academy of Social Sciences. p. 14.

- ^ Shin, Jae-Eun (1 January 2018). Region Formed and Imagined: Reconsidering Temporal, Spatial and Social Context of Kāmarūpa, in Lipokmar Dzuvichu and Manjeet Baruah (eds), Modern Practices in North East India: History, Culture, Representation, London and New York: Routledge, 2018, pp. 23–55.

- ISBN 978-0-8387-5144-2. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

- ^ Witzel 1993, p. 267.

- ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4, retrieved 5 February 2022

- ISBN 81-8569-224-6.

- ^ Narottam, Kundu (1963). Caste and class in pre-Muslim Bengal (PDF) (Thesis). University of London.

- ISBN 9789325976689.

- ^ "Reflections on Kulin Polygamy, p2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8387-5144-2. Archivedfrom the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-1928-9685-8.

- ISBN 9780197675908.

- ^ "Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal". Time. 2 August 1971.

- ^ Das, S. (1990). Communal Violence in Twentieth Century Colonial Bengal: An Analytical Framework. Social Scientist, 18(6/7), 21. doi:10.2307/3517477

- ^ Bhattacharya, "Raybaghini o Bhurishrestha Rajkahini"

- ^ Bhattacharya, "Raybaghini o Bhurishrestha Rajkahini"

- ^ Dutt, Ajanta (6 July 2016). "Book review 'A Nation in Making': Banerjea's nation-A man and his history". The Asian Age. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Khan, Fatima (8 April 2019). "Bankim Chandra — the man who wrote Vande Mataram, capturing colonial India's imagination". The Print. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Kishore Kumar birthday: His favourite songs". India Today. 4 August 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Protocol to keep President Pranab off Puja customs". Hindustan Times. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-136-10426-8.

References

- An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, by Damodar Dharmanand Kosāmbi, Popular Prakasan,35c Tadeo Road, Popular Press Building, Bombay-400034, First Edition: 1956, Revised Second Edition: 1975.

- Atul Sur, Banglar Samajik Itihas (Bengali), Calcutta, 1976

- NN Bhattacharyya, Bharatiya Jati Varna Pratha (Bengali), Calcutta, 1987

- RC Majumdar, Vangiya Kulashastra (Bengali), 2nd ed, Calcutta, 1989.

- Bhattacharya, Jogendra Nath (1896). Hindu Castes and Sects: An Exposition of the Origin of the Hindu Caste System and the Bearing of the Sects toward Each Other and toward Other Religious Systems. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink. p. iii.

- Dutta, K; Robinson, A (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-14030-4

- Siddiq, Mohammad Yusuf (2015). Epigraphy and Islamic Culture: Inscriptions of the Early Muslim Rulers of Bengal (1205–1494). Routledge. ISBN 9781317587460.

- Witzel, Michael (1993). "Toward a History of the Brahmins". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 113 (2): 264–268. JSTOR 603031.

Further reading

- Chaudhuri, Hemotpaul (5 June 2022). Journey Of The Dutta - Kannauj to Bengal.