Boris Gusman

Boris Yevseyevich Gusman (1892–1944) was a Soviet author, screenplay writer, theater director, and columnist for

Life

Pravda and art criticism

As a young man Gusman was a violinist and played for the

It was in 1921 that Gusman and his family moved to Moscow, where he began writing for Pravda.[1] He was recognized as an important film critic, and from 1923 onwards headed Pravda's theatre section.[3] Gusman rejected arguments among some Soviet filmmakers, associated with the Proletkult movement, that contributing to a new Soviet cinema required abandoning the history of film altogether. Gusman wrote that the new cinema "must be built brick by brick, making use of everything that is healthy about the New World, and that which is good about the old."[4] Gusman responded favorably to candid films pioneered by Dziga Vertov called Kino-Pravda. He described them as "lively… striking… and interesting," but criticized the lack of connection between scenes and the absence of unifying themes.[4]

Musical career

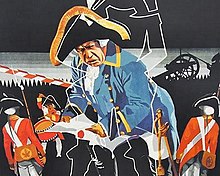

In 1929 Gusman, as deputy director, led the State Bolshoi Academic Theater's effort to stage Prokofiev's Pas d'Acier with new cast and choreography.[5] Gusman remained with the Bolshoi Theatre through 1930, and in 1933 became head of the arts division of the Soviet Central Radio Administration.[3] Gusman played a central role in working with Prokofiev in the musical and cinematic production of Lieutenant Kijé.[6] Following the success of the film, in 1934 Gusman organized a broadcast concert of the music with Moscow Radio Orchestra.[5][6]

In 1934, Gusman negotiated a contract between Prokofiev and the All-Union Radio Committee, helping the composer return to Russia. Gusman also offered him a tremendous sum of 25,000 rubles for one of a series of commissioned works: the

Purges and death

In 1937, Gusman lost his position as director of the Moscow Radio Orchestra,

Arrested in one of

Gusman's son Israel survived the purges, and would go on to head the Gorky Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra from 1957 until 1987.[1]

Filmography

- 1928: The Living Corpse, adapted from a story by Leo Tolstoy.

- 1929: Merry Canary, a story about intelligence and espionage.

- 1935: On the Strangeness of Love, a Vaudeville comedy set in Crimea.

Books

- 1923: Literary portraits: one hundred poets (Tver)

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Smirnov, Stanislav (24 May 2012). "Don't Part Ways with the Muses". Pravda. Archived from the original on 2014-01-15. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Markov, Vladimir (1968). Russian Futurism: A History. University of California Press.

- ^ a b c Keldysh, Yu. V. (1973). Muzykal'naia entsiklopediia, Moskva: Sovetskaia entsiklopediia, Sovetskii kompozitor. Translated by Choate, Frederick. Moskva.

- ^ a b Tsivian, Yuri (2004). Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties. Indiana University Press.

- ^ a b Morrison, Simon (2008). The People's Artist: Prokofiev's Soviet Years. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Bartig, Kevin (2013). Composing for the Red Screen: Prokofiev and Soviet Film. Oxford University Press.

- ^ JSTOR 10.1525/jm.2006.23.2.227.

- ^ Morrison, Simon (2013). Lina and Serge: The Love and Wars of Lina Prokofiev. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ a b Medvedeva, Vera (August 2008). ""LOVE FOR A WOMAN DETERMINES A LOT IN LIFE" – INTERVIEW WITH YURI LARIN". Russkiy Mir Foundation. 7. Archived from the original on 2014-01-14.

- ^ S2CID 144576497.

- ^ S̆ilde, Ādolphs (1958). The Profits of Slavery: Baltic Forced Laborers and Deportees Under Stalin and Krushchev. Latvian National Foundation in Scandinavia.

- ^ "Gusman, Boris., Russian Art and Books, Imperial, Soviet and Emigrant Paintings, Graphics, Prints, Illustrated Russian Books & Magazines, Sheet Music, Ephemera, Photography, Posters, Autographs, etc., Avant-garde Antiquarian Ballet Russe Bilibin California Chagall Cold War Constructivism Constructivist Coronation Filonov Futurism Klutsis Leon Bakst Lissitzky Malevich Meyerhold Propaganda Rodchenko Royalty San Diego Stenberg Tatlin VKHUTEMAS". www.russianartandbooks.com. Retrieved 4 January 2019.