Cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts

| Cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts | |

|---|---|

| Other names | CRMCC |

| |

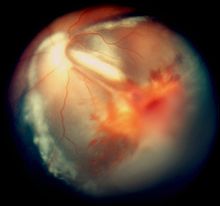

| Vitreous hemorrhage and exudative retinal detachment resembling Coats' disease in a child with cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Cerebroretinal

Cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts is alternatively known as the Coats plus syndrome,[3] a reference to its most typical ocular phenotype.

Signs and Symptoms

Presentation

Before birth

A child who has inherited this disorder will grow slower than normal in the uterus before birth and typically will be born before term.[1][2][3] The pregnancy can be complicated by gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia.[citation needed]

After birth

The majority of affected children present with symptoms and signs relating to the eyes such as

Brain

Neurologic symptoms and signs vary depending on the site of the brain abnormalities. Common symptoms are partial epilepsy, asymmetric spasticity, ataxia and cognitive impairment.[1][2][3] The latter affects visuospatial and visuoconstructive skills first. The intracranial pressure can be elevated if cysts develop in the brain. Migraine-like headaches can occur.[citation needed]

Eyes

Smaller

In some eyes, retinal vessels form small nodules on the surface of the retina, known as

Gastrointestinal tract

Recurrent

Blood

Many affected children develop

Bones

The long bones show osteopenia and pathologic fractures can occur.[1][2][4][5]

Skin, nails and hair

Some children have sparse and greying hair,

General

Most patients continue to grow poorly after birth.[1][3]

Genetics

Typical childhood-onset cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts is caused by

Pathophysiology

Angiomas and numerous abnormal, small, dilated telangiectatic vessels with thickened, sclerotic and calcified walls have been found in those brain areas which also show calcifications.[1][2]

By analogy to

Diagnosis

Clinical

The retinal changes are easily identified by

Imaging findings

The most consistent finding are widespread calcifications, which involve the

Magnetic resonance imaging shows additionally diffuse or patchy white matter changes, especially in the periventricular region, the thalami and the internal capsule. Cerebellar and brainstem lesions are less common. Imaging also uncovers parenchymal cysts situated mainly in the thalamic region and more rarely in the brainstem, the parietal lobe and the frontal lobe.

The long bones may be osteopenic and various skeletal changes are found in several patients, such as metaphyseal sclerosis and mild flaring, which is most pronounced in the femur and tibia.[3][4][5]

Laboratory findings

The cerebrospinal fluid and blood tests are typically normal, except for anemia and thrombocytopenia in some children.[1][2][4]

Screening

Because of the rarity of the syndrome, it is not routinely screened before birth.

Management

Seizures are managed with anticonvulsive medications.

Laser coagulation or cryoablation (freezing) of the retina can be used to destroy the abnormal blood vessels. Retinal detachment is repaired with a scleral buckle or with vitrectomy. Removal or enucleation of the eye is a last resort option if the eye already has become blind and painful.[citation needed]

Repeated blood transfusions may be needed to control anemia, and thrombocytopenia can be managed with splenectomy.[1]

Prognosis

The neurological symptoms are progressive and can lead to severe spasticity, bulbar symptoms and dysarthria within one to two decades.[1][3] The life span is shorter than normal. Death occurs between 2 and 30 years of age, depending on the severity of the syndrome. The immediate cause of death is pneumonia, fulminant intestinal bleeding or multiple organ dysfunction.[1]

If not treated, the retinal detachment can lead to

Epidemiology

This syndrome is usually sporadic although families with two or more affected siblings of both sexes are known.[1][3]

History

A child who was eventually diagnosed with cerebroretinal microangiopathy with calcifications and cysts was first described in the literature in 1987.[9][15] The disorder was suspected of being allelic with either the Revesz syndrome[2] or leukoencephalopathy with calcifications and cysts.[1][2] However, Revesz syndrome, a severe variant of dyskeratosis congenita, was later shown to result from heterozygous dominant mutations in the TINF2 gene,[16] which encodes TRF1-interacting nuclear factor 2, a major component of the telomere protecting shelterin complex, and individuals with the leukoencephalopathy with calcifications and cysts phenotype have not had mutations in the CTC1 gene.[7][8]

Before the causative mutation was identified, mutations were sought from the

Coats' disease is named after George Coats.[17][18]

References

- ^ S2CID 28941194.

- ^ S2CID 39256035.

- ^ PMID 15002047.

- ^ PMID 11992766.

- ^ S2CID 19482634.

- ^ PMID 21373254.

- ^ S2CID 205343417.

- ^ PMID 22387016.

- ^ PMID 3402627.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: CTC1".

- ^ PMID 19854131.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: OBFC1".

- ^ "Entrez Gene: TEN1".

- PMID 6502405.

- PMID 3556653.

- PMID 18252230.

- Who Named It?

- ^ Coats G (Nov 1908). "Forms of retinal disease with massive exudation". R Lond Ophthalmol Hosp Rep. 17 (3): 440–525.