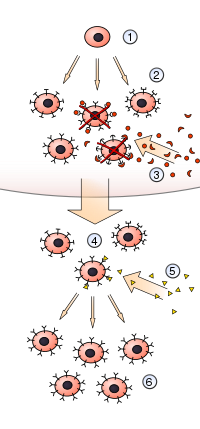

Clonal selection

1) A hematopoietic stem cell undergoes differentiation and genetic rearrangement to produce

2) immature lymphocytes with many different antigen receptors. Those that bind to

3) antigens from the body's own tissues are destroyed, while the rest mature into

4) inactive lymphocytes. Most of these never encounter a matching

5) foreign antigen, but those that do are activated and produce

6) many clones of themselves.

In

The theory states that in a pre-existing group of lymphocytes (both B and T cells), a specific antigen activates (i.e. selects) only its counter-specific cell, which then induces that particular cell to multiply, producing identical

Postulates

The clonal selection theory can be summarised with the following four tenets:

- Each lymphocyte bears a single type of receptor with a unique specificity (generated by V(D)J recombination).

- Receptor occupation is required for cell activation.

- The differentiated effector cells derived from an activated lymphocyte bear receptors of identical specificity as the parent cell.

- Those lymphocytes bearing receptors for self molecules (i.e., endogenousantigens produced within the body) are destroyed at an early stage.

Early work

In 1900, Paul Ehrlich proposed the so-called "side chain theory" of antibody production. According to it, certain cells exhibit on their surface different "side chains" (i.e. membrane-bound antibodies) able to react with different antigens. When an antigen is present, it binds to a matching side chain. Then the cell stops producing all other side chains and starts intensive synthesis and secretion of the antigen-binding side chain as a soluble antibody. Though distinct from clonal selection, Ehrlich's idea was a selection theory far more accurate than the instructive theories that dominated immunology in the next decades.

In 1955, Danish immunologist

In 1957,

Burnet's clonal selection theory

Later in 1957, Australian immunologist

In 1958, Gustav Nossal and Joshua Lederberg showed that one B cell always produces only one antibody, which was the first direct evidence supporting the clonal selection theory.[6]

Theories supported by clonal selection

Burnet and

In 1959, Burnet proposed that under certain circumstances, tissues could be successfully transplanted into foreign recipients. This work has led to a much greater understanding of the immune system and also great advances in tissue transplantation. Burnet and Medawar shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960.

In 1974, Niels Kaj Jerne proposed that the immune system functions as a network that is regulated via interactions between the variable parts of lymphocytes and their secreted molecules. Immune network theory is firmly based on the concept of clonal selection. Jerne won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984, largely for his contributions to immune network theory.

See also

References

Further reading

- Podolsky, Alfred I. Tauber; Scott H. (1997). The Generation of Diversity : Clonal Selection Theory and the Rise of Molecular Immunology (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-00182-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - "Biology in Context - The Spectrum of Life" Authors, Peter Aubusson, Eileen Kennedy.

- Forsdyke D.R. (1995). "The Origins of the Clonal Selection Theory of Immunity". FASEB Journal. 9 (2): 164–66. S2CID 38467403.

External links

- Animation of clonal selection Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine from the Walter & Elisa Hall institute.