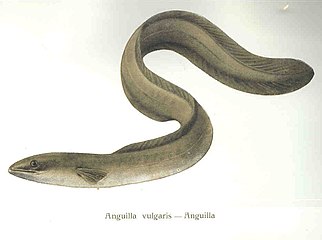

European eel

| European eel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anguilliformes |

| Family: | Anguillidae |

| Genus: | Anguilla |

| Species: | A. anguilla

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anguilla anguilla | |

| |

| Freshwater range of wild European eel | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Muraena anguilla Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla)[3] is a species of eel.[4] They are critically endangered due to hydroelectric dams, overfishing by fisheries on coasts for human consumption, and parasites.[4][5][6][7]

Description

European eels are normally around 45–65 centimetres (18–26 in) and rarely reach more than 1.0 metre (3 ft 3 in), but can reach a length of up to 1.33 metres (4 ft 4 in) in exceptional cases.[8] In addition, they range from having 110 to 120 vertebrae.[9] While European eels tend to live approximately 15–20 years in the wild, some captive specimens have lived for over 80 years. A specimen known as "the Brantevik Eel" lived for 155 years in the well of a family home in Brantevik, a fishing village in southern Sweden.[9][10][11]

Ecology

Eels tend to range from 0 to 700 meters underwater and after spawning in the Sargasso Sea, disperse North throughout the Atlantic Ocean, its coasts, and the rivers that empty into it.[12] Feeding occurs mainly at night, via scent and prey consists of worms, fish (including ones too big to eat without biting off chunks), mollusks such as slugs, crustaceans such as crayfish, and plankton on occasion when it's populous in large quantities.[13][14] European eels are preyed upon by bigger eels, herons, cormorants, and pike. Seagulls also prey on elvers.[14] Eels usually find and compete for shelter by hiding in plants or tube-shaped crevices in rocks. They also hide in muddy fields when inland.[14]

Conservation status

The European eel is a

Sustainable consumption

Eels have been important sources of food both as adults (including

Breeding projects

As the European eel population has been falling for some time, several projects have been started. In 1997, Innovatie Netwerk in the Netherlands initiated a project where they attempted to get European eels to breed in captivity by simulating the 6,500 km (4,000 mi) journey from Europe to the Sargasso Sea with a swimming machine for the fish.[22][23]

The first to achieve some success was DTU Aqua, a part of the

To further the research, the PRO-EEL project, led by DTU Aqua and involving several research institutes elsewhere in Denmark (

Life history

Much of the European eel's life history was a mystery for centuries, as fishermen never caught anything they could identify as a young eel. Unlike many other migrating fish, eels begin their life cycle in the ocean and spend most of their lives in fresh inland water, or brackish coastal water, returning to the ocean to spawn and then die. In the early 1900s, Danish researcher Johannes Schmidt identified the Sargasso Sea as the most likely spawning grounds for European eels.[32] The larvae (leptocephali) drift towards Europe in a 300-day migration.[33]

When approaching the European coast, the larvae metamorphose into a transparent larval stage called "glass eel", enter estuaries, and many start migrating upstream. After entering their continental habitat, the glass eels metamorphose into

Sometimes the eel will never enter freshwater, and remain in their marine environment their entire life. Others grows up in brackish water, or migrate between saltwater, brackish water and freshwater several times in their lifetime.[37]

Magnetoreception has also been reported in the European eel by at least one study, and may be used for navigation.[38]

-

Life cycle of the European eel

-

Glass eels at the transition from ocean to fresh water

-

Mature silver-stage European eels migrate back to the ocean

Commercial fisheries

Production

The eel farming industry uses recirculating pools to raise glass eels taken from the wild for 8 months to 2 years until they mature enough for sale.[39] Valliculture on coasts through the use of weirs is also utilized instead of recirculating pools for eel farming.[39] New eels are quarantined to prevent disease spread and eels are sorted by size every couple weeks to prevent cannibalism[39] and remove dead animals.[40] A range of 23°C to 28°C is optimal for growth and protein based pellets and pastes are utilized as food sources for the eels after an initial few days of cod roe for the small glass ones.[41][39][40] European eels typically have a feed conversion ratio (FCR) in the range of 1.8-2.5, although European fisheries are typically in the 1.6-1.7 range.[40][42][43] Filters are essential for eliminating waste and ensuring the eels have clean water to live in.[39] Eels are typically transported via road in tanks with water or via air in styrofoam boxes with a beaker of ice. The beakers keep condensation on the outside and ice on inside to keep the environment moist enough for the 1-3kg of eels to survive and also keep the temperature low enough.[40]

Diseases/parasites in fisheries

Industry

The exportation of European Eels has been restricted since 2010, yet on average 44% of eel sales in the