HIV/AIDS in Malawi

As of 2012[update], approximately 1,100,000 people in

Due to several successful television and radio campaigns by the Malawian government and non-governmental organizations in Malawi, levels of awareness regarding HIV/AIDS are high among the general population.[2] However, many men have adopted fatalistic attitudes in response to the epidemic, convincing themselves that death from AIDS is inevitable; on the other hand, some have implemented preventive techniques such as partner selection to try to reduce their risk of infection.[3] Although many women have developed strategies to protect themselves from HIV, women are more likely to be HIV-positive than men in Malawi.[1] The epidemic has affected sexual relationships between partners, who must cooperate to protect themselves from the disease.[4] In addition, many teachers exclude HIV/AIDS from their curricula because they are uncomfortable discussing the topic or because they do not feel knowledgeable about the issue, and, therefore, many children are not exposed to information about HIV/AIDS at school.[5] Finally, the epidemic has produced significant numbers of orphans in Malawi, leaving children vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.[6]

History

The first case of HIV/AIDS in Malawi was reported at Lilongwe's Kamuzu Central Hospital in 1985.[7] President Hastings Banda, who was in power at the time, responded with several small-scale prevention initiatives and created the National AIDS Control Programme, a division of the Ministry of Health, to manage the growing epidemic.[1] Banda believed that issues relating to sex, including HIV transmission, should not be addressed in the public sphere; during this time, it was illegal for Malawian citizens to discuss the epidemic openly.[8] In 1989, Banda introduced a five-year World Bank Medium Term Plan to combat the epidemic, but HIV prevalence had already increased drastically at this point.[1]

In 1994, when

Malawians gained access to

Awareness and risk perception

Despite Malawi's limited health and educational infrastructure, knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS is high among many people living in both urban and rural Malawi.

Personal traits such as age, gender, location, and education correlate, either positively or negatively, with HIV/AIDS awareness levels. For example, older women have demonstrated higher levels of knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS than younger women in Malawi.

The aforementioned study by Barden-O'Fallon et al., which surveyed 940 women and 661 men, indicated that, despite their knowledge and awareness, many people in Malawi do not feel

Education

Students in Malawi have expressed high levels of dissatisfaction regarding the HIV/AIDS-related education and support they receive at school.[6] According to a survey of students in Malawi, most secondary students do not believe that the HIV/AIDS curricula at their schools provide them with an adequate understanding of the disease.[6] Although the Malawian government and non-governmental organizations have conducted many campaigns to improve awareness about HIV/AIDS in schools, there is still a significant shortage of age-appropriate audio and visual educational materials relating to HIV/AIDS available to instructors, particularly in rural areas.[6] In addition, most teachers cannot identify the students in their classes who have been personally affected by the epidemic, either through friends or relatives, which suggests that school-based support for HIV/AIDS is minimal.[6] However, despite this lack of support, surveys indicate that children who have been affected by the epidemic do not usually experience HIV/AIDS-based discrimination at school.[6]

Most teachers are required to address HIV/AIDS in their curricula; although instructors are, for the most part, committed to helping their students understand and avoid the disease, they face many obstacles that prevent them from informing their students about HIV/AIDS in productive ways.[5] For example, some teachers cannot advise their students to remain faithful to their sexual partners without seeming hypocritical because they engage in extramarital sexual relations themselves.[5] Others feel uncomfortable discussing sexual matters with their students, and some believe that, due to their limited training, they are not knowledgeable enough about HIV/AIDS to direct classroom discussions about the disease.[5] In addition, many teachers feel unsupported by community members, who often either deny the extent of the epidemic or believe that HIV/AIDS should not be addressed in the classroom.[5]

Affected groups

Although the HIV/AIDS epidemic has affected men, women, and children in Malawi, certain factors such as

Men

Due to the vast scope of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, many Malawian men believe that HIV contraction and death from AIDS are inevitable.

However, despite these widespread feelings of fatalism, some men believe that they can avoid HIV contraction by modifying their personal behaviors.

Women

According to

Many women are convinced that their husbands are putting their lives at risk by engaging in extramarital sexual relations without using protection; however, because of their secondary status, they are often unwilling to initiate discussions about HIV/AIDS in the home.

However, despite their vulnerability, some women in rural Malawi believe that they do, to a certain extent, have control over their own health and well-being.

Children

The number of orphaned children in Malawi has increased dramatically since the HIV/AIDS epidemic began in 1985, with certain surveys indicating that more than 35% of schoolchildren have experienced the death of at least one parent due to HIV/AIDS.

When parents die of HIV/AIDS,

Evidence suggests that schoolchildren in Malawi are at risk of being exposed to HIV by their teachers, who sometimes value them as sexual partners because they believe that children have not yet been exposed to the virus.

Marriage and relationships

Although couples are starting to use condoms during extramarital intercourse more frequently,

Many different sources of information can motivate discussion about HIV/AIDS among married couples.[14] After hearing information about HIV/AIDS at local health facilities or during conversations with friends or family members, people are more likely to address the risk of HIV contraction with their spouses.[14] In addition, women are more likely than men to mention the dangers of HIV/AIDS when they suspect that their spouses are engaging in extramarital sexual relations. According to a 2003 study by Eliya Msiyaphazi Zulu and Gloria Chepngeno, although higher levels of education do correspond to greater knowledge about HIV/AIDS, education levels do not significantly impact the likelihood that couples will discuss HIV-related prevention strategies.[14]

Economic impact

A 2002 study conducted by

CARE International proposes several strategies that might reduce the destructive economic impact of HIV/AIDS on

Impact on health services

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Malawi has been characterized by drastic declines in the number of health workers available to provide treatment and care and increasing strain on health services: more than half of all hospital admissions in Malawi are related to HIV/AIDS.

While migration to more developed countries in search of better opportunities, also known as "

Malawi has adopted task shifting strategies to overcome the shortage of workers available for HIV/AIDS treatment and care.

Interventions

Malawi has taken many steps towards slowing the spread of HIV/AIDS, such as increasing access to condoms and improving

Antiretroviral therapy

The number of people using antiretroviral therapy in Malawi has increased dramatically in the past decade: between 2004 and 2011, an estimated 300,000 people gained access to antiretroviral treatment.[1] In addition to improving access to antiretroviral therapy, in 2008, Malawi introduced the WHO's treatment guidelines for antiretroviral therapy, which improved the quality of treatment available to Malawians.[1] However, Malawi's proposal for a new antiretroviral treatment plan in 2011, which would have cost $105 million per year, was rejected by the Global Fund, threatening Malawi's ability to continue expanding access to antiretroviral treatment.[1]

In 2000, Malawi's Ministry of Health and Population began developing a plan to distribute antiretroviral drugs to the population, and, as of 2003, there were several sites providing antiretroviral drugs in Malawi.[17] The Lighthouse, a trust in Lilongwe that fights HIV/AIDS, provides antiretroviral drugs at a cost of 2,500 kwacha per month.[17] Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre provides antiretroviral therapy through its outpatient department, and Médecins Sans Frontières distributes antiretroviral drugs to patients for free in the Chiradzulu and Thyolo Districts.[17] Many different private providers sell antiretroviral drugs, particularly in cities; however, very few patients can afford to receive drugs from the private sector in Malawi.[17] In addition, private providers are not currently required to obtain certification before selling antiretroviral drugs, and, therefore, this practice is not closely monitored.[17] Finally, some employees receive access to antiretroviral drugs through the health insurance policies provided by their employers, but this practice is not widespread.[17]

Due to the advent of antiretroviral drugs, HIV/AIDS has become a manageable disease for people who can access and afford treatment; however, antiretroviral therapy remains largely unaffordable and inaccessible to most people in Malawi.

Condom distribution

Although

Non-governmental organizations such as

Voluntary counseling and testing

People living in areas with high rates of HIV/AIDS face several psychological barriers when deciding whether to undergo testing for HIV.[1] For example, people may prefer not to know if they are HIV-positive because, due to the obstacles they often face in gaining access to antiretroviral drugs, many view HIV/AIDS diagnoses as death sentences.[1] Others may simply believe that they are HIV-negative, either because they practice strict monogamy and consistently use condoms during sexual intercourse or because they are in denial about the prevalence of the disease.[1] However, despite these barriers, both mobile and static testing services have become more widely available in Malawi recently: 1,392 testing and counseling sites existed in 2011.[1] Certain non-governmental organization such as the Malawi AIDS Counseling and Resource Organisation (MACRO) provide door-to-door counseling and testing services, which have drastically improved the accessibility of HIV testing.[7]

See also

- Sub-Saharan Africa

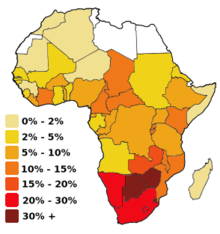

- HIV/AIDS in Africa

- Diseases of poverty

- Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS

- Misconceptions about HIV and AIDS

- AIDS orphan

- Healthcare in Malawi

- Sex for Fish

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj "HIV & AIDS in Malawi". AVERT. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ S2CID 9024663.

- ^ PMID 15110420.

- ^ PMID 17240504.

- ^ a b c d e Kachingwe, Sitingawawo (2005). "Preparing Teachers as HIV/AIDS Prevention Leaders in Malawi: Evidence from Focus Groups". International Electronic Journal of Health Education. 8: 193–204.

- ^ S2CID 154783763.

- ^ a b Government of Malawi (2012). GLOBAL AIDS RESPONSE PROGRESS REPORT: Malawi Country Report for 2010 and 2011 (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ PMID 17110008.

- ^ PMID 17600974.

- PMID 31452842.

- ^ S2CID 32033946.

- ^ S2CID 11483329.

- S2CID 27946968.

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d e f g h Impact of HIV/AIDS on agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods in the central region of Malawi. Malawi: CARE International. January 2002. pp. 5–10.

- ^ S2CID 414056.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kemp, Julia; Jean Marion Aitken; Sarah LeGrand; Biziwick Mwale (2003). "Equity in health sector responses to HIV/AIDS in Malawi". Regional Network for Equity in Health in Southern Africa (EQUINET).

- ^ S2CID 33739153.