History of combinatorics

The mathematical field of

Earliest records

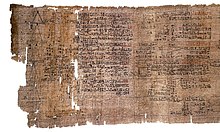

The earliest recorded use of combinatorial techniques comes from problem 79 of the

In Greece, Plutarch wrote that Xenocrates of Chalcedon (396–314 BC) discovered the number of different syllables possible in the Greek language. This would have been the first attempt on record to solve a difficult problem in permutations and combinations.[2] The claim, however, is implausible: this is one of the few mentions of combinatorics in Greece, and the number they found, 1.002 × 10 12, seems too round to be more than a guess.[3][4]

Later, an argument between Chrysippus (3rd century BCE) and Hipparchus (2nd century BCE) of a rather delicate enumerative problem, which was later shown to be related to Schröder–Hipparchus numbers, is mentioned.[5][6] There is also evidence that in the Ostomachion, Archimedes (3rd century BCE) considered the configurations of a tiling puzzle,[7] while some combinatorial interests may have been present in lost works of Apollonius.[8][9]

In India, the Bhagavati Sutra had the first mention of a combinatorics problem; the problem asked how many possible combinations of tastes were possible from selecting tastes in ones, twos, threes, etc. from a selection of six different tastes (sweet, pungent, astringent, sour, salt, and bitter). The Bhagavati is also the first text to mention the choose function.[10] In the second century BC, Pingala included an enumeration problem in the Chanda Sutra (also Chandahsutra) which asked how many ways a six-syllable meter could be made from short and long notes.[11][12] Pingala found the number of meters that had long notes and short notes; this is equivalent to finding the

The ideas of the Bhagavati were generalized by the Indian mathematician

The ancient Chinese book of divination I Ching describes a hexagram as a permutation with repetitions of six lines where each line can be one of two states: solid or dashed. In describing hexagrams in this fashion they determine that there are possible hexagrams. A Chinese monk also may have counted the number of configurations to a game similar to

The

Combinatorics in the West

Combinatorics came to Europe in the 13th century through mathematicians

Both Pascal and Leibniz understood that the

In the 18th century,

Contemporary combinatorics

In the 19th century, the subject of

Notes

- ^ ISBN 0-262-57172-2. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ISBN 0486240738.

- ^ a b Dieudonné, J. "The Rhind/Ahmes Papyrus - Mathematics and the Liberal Arts". Historia Math. Truman State University. Archived from the original on 2012-12-12. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ISBN 0-8284-0218-3.

- S2CID 122758966.

- JSTOR 2974582.

- ^ Netz, R.; Acerbi, F.; Wilson, N. "Towards a reconstruction of Archimedes' Stomachion". Sciamvs. 5: 67–99.

- S2CID 121613986.

- ^ Huxley, G. (1967). "Okytokion". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 8 (3): 203–204.

- ^ a b "India". Archived from the original on 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ JSTOR 25678735.

- arXiv:math/0703658.

- Bhaskara. "The Lilavati of Bhaskara". Brown University. Archived from the originalon 2008-03-25. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ^ Swaney, Mark. "Mark Swaney on the History of Magic Squares". Archived from the original on 2004-08-07.

- ^ "Middle East". Archived from the original on 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ The short commentary on Exodus 3:13

- ^ History of Combinatorics, chapter in a textbook.

- ^ Arthur T. White, ”Ringing the Cosets,” Amer. Math. Monthly 94 (1987), no. 8, 721-746; Arthur T. White, ”Fabian Stedman: The First Group Theorist?,” Amer. Math. Monthly 103 (1996), no. 9, 771-778.

- ^ Devlin, Keith (October 2002). "The 800th birthday of the book that brought numbers to the west". Devlin's Angle. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ Leibniz's habilitation thesis De Arte Combinatoria was published as a book in 1666 and reprinted later

- ISBN 0-486-44233-0.

- ^ Hodgson, James; William Derham; Richard Mead (1708). Miscellanea Curiosa (Google book). Volume II. pp. 183–191. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ O'Connor, John; Edmund Robertson (June 2004). "Abraham de Moivre". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ISBN 0-7923-8480-6. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ "Combinatorics and probability". Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ISBN 978-0821810255.

- ^ ISBN 978-1107602625.

- JSTOR 2319793.

- ISBN 9780821837368.

- .

- .

- .

- ^ "Wolf Foundation Mathematics Prize Page". Wolffund.org.il. Archived from the original on 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

References

- N.L. Biggs, The roots of combinatorics, Historia Mathematica 6 (1979), 109–136.

- Katz, Victor J. (1998). A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, 2nd Edition. Addison-Wesley Education Publishers. ISBN 0-321-01618-1.

- O'Connor, John J. and Robertson, Edmund F. (1999–2004). St Andrews University.

- Rashed, R. (1994). The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra. London.

- Wilson, R. and Watkins, J. (2013). Combinatorics: Ancient & Modern. Oxford.

- Stanley, Richard (2012). Enumerative combinatorics (2nd ed. ed.), 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107602629.