Humaitá campaign

The Humaitá campaign or the Cuadrilátero campaign was the third, longest and deadliest campaign of the

All operations were halted from September 1866 to July 1867, when the allied offensive resumed. By the middle of the following year, however, little progress had been made when the fortifications were overrun by the Brazilian fleet. Faced with this novelty, the Paraguayan forces installed a new defensive line, much closer to Asunción, abandoning the "Cuadrilátero". Ultimately, the campaign resulted in a costly but unqualified success for the Triple Alliance.

Background

The Paraguayan War was caused by the aggression of Paraguay against Brazil and Argentina in response to the participation of both countries in the Uruguayan War, which altered the strategic balance of power in the Southern Cone.

Until then, Paraguay had managed with great efforts to sustain its autonomous system of government that sustained autonomous economic growth and development, which was supported by a very accentuated economic protectionism.[5] It had also managed to sustain its claims to nearby territories, which were disputed with Brazil and Argentina. From the Paraguayan point of view, the breakdown of this balance endangered its economic autonomy and hindered its efforts to prevent the territories in conflict from being annexed by their powerful neighbors.[6]

The war broke out when the news reached Asunción that Brazilian troops had invaded Uruguay, ignoring the Paraguayan warning not to do so. Paraguayan troops invaded the Province of Mato Grosso in western Brazil, isolated from the rest of the country. The campaign was swift and successful, and within two months most of the province had been occupied by Paraguayan forces.[7]

Then, Solano López asked Argentine President Bartolomé Mitre for authorization to cross Argentine territory in order to attack Brazil. Given the Argentine refusal, López declared war on Argentina on March 19,[8] and began the Corrientes campaign, from there, to Rio Grande do Sul.[9][10]

When news of the invasion arrived, the Treaty of the Triple Alliance between the Argentine Republic, the Empire of Brazil and the Oriental Republic of Uruguay was signed in Buenos Aires.[11]

In its early stages, the campaign was successful for Paraguay, but defeats soon mounted such as on June 11, when the Paraguayan fleet was destroyed in the

The rest of the Paraguayan army withdrew to its own territory. The allied army concentrated in the city of Corrientes, where it was harassed by small Paraguayan incursions, which, although achieving a victory in the Battle of Pehuajó, failed to prevent the organization of the invasion of Paraguay.

The invasion

Before starting the invasion, the Brazilian war fleet, supported only partially by the Argentine Navy, explored the enemy coasts only from a short distance from the point called "Tres Bocas", that is, the confluence of the Paraguay River with the Paraná. Brazilian admiral Joaquim Marques Lisboa, then Viscount of Tamandaré, maintained a very prudent attitude, ensuring only the possibility of landing, without venturing down into unknown rivers, especially the Paraná River.

At the beginning of April, the Brazilian forces took possession of a small island in front of the Itapirú Fortress, from where they could bombard the fort, since it was just at a distance that the Paraguayan guns, of inferior quality, had no range to fire at them while at the same time coming under fire by the rifled cannons of the Brazilian artillery. For that reason, on April 10, a Paraguayan division moved by canoe tried to regain possession of the island. The Brazilian response in the battle of Purutué Bank was a comprehensive Allied victory. The victorious Brazilian commander, colonel Villagran Cabrita, was reckless and boarded a boat on the north side of the island, where he was writing the victory report, when he was hit by a Paraguayan cannon shot, which killed him on the spot. The island was since called Isla Cabrita.[13]

On 16 April 1866, an allied army of 42,200 men began to cross the Paraná River, entering Paraguayan territory.[14] The force was made up of 29,000 Brazilians, 11,000 Argentines and just over 2,000 Uruguayans. Some 20,000 were cavalrymen, but about a fifth of them were dismounted.[15]

The place chosen for the first landing was the coast of the Paraguay River, less than 1,000 meters from its mouth in the Paraná. Although López had prepared his forces for a landing somewhere nearby, the point chosen by the attackers had been relatively neglected. The first man to make landfall was Brazilian general Manuel Luís Osório, then Baron of Erval, commander of the imperial forces, accompanied by a scant escort. Throughout the war, Osório would be noted for his personal audacity and bravery, leading frontal attacks.[15]

On the 18th, the Allied forces captured the Itapirú Fortress on the right bank of the Paraná River as it was reduced to rubble by the cannons of the Brazilian fleet.[16]

Mitre advanced in a straight line towards the center of the defensive line organized by López located in the Humaitá Fortress, which prevented the passage of ships on the Paraguay River. In doing so he unwisely exposed his troops, but López made a major mistake as instead of waiting for the invaders in their defensive lines, the Paraguayan forces attacked the allies at Estero Bellaco. The forces sent to intercept the allied advance at Estero Bellaco had orders to do what damage they could and withdraw. But, seeing themselves victorious, they continued their advance, which gave time for the reaction of the Argentine troops, who defeated them. However, the Paraguayans managed to stop the advance in the open field at Tuyutí, where the invading forces limited themselves to waiting to be attacked to defend themselves.

The battlefield

From the mouth of the Paraguay River in the Paraná to Humaitá, there was less than 30 km. The strip of land corresponding to that section, with a maximum width of 20 km, would be the battlefield for 2 years and 4 months. With the exception of some other battles in Mato Grosso, all the battles of the period took place in that narrow territory. It was a marshy land, crossed by two swamps that ran from west to east, and were impossible to cross except for a few places. To the south lied Estero Bellaco, which in turn divides into two tributaries, Estero Bellaco Sur and Estero Bellaco Norte. To the north lied the Estero Rojas. Between the swamps there were relatively dry areas, known as potreros, the most important of which were the extensive Potrero Obella to the north and the Potrero Tuyutí, which would be the terrain chosen by Mitre to camp his troops. Other potreros of lesser importance were smaller camps of the Paraguayans, such as Yataytí Corá and Paso Pucú.

With few exceptions, all the land was subject to flooding, and was covered by strips of impenetrable jungle, especially reedbeds and rushes. The jungle was an appropriate place for Paraguayan soldiers to lay in ambush, especially against invading armies which were foreign to the terrain.[17]

The first Paraguayan defensive lines located in the south were formidable and were centered on a series of fortifications, among which the most important were the fortresses of Curupayty, Humaitá, on the left bank of the Paraguay River, and the Timbó on the other side of the river, in what is now the Chaco province. All three forts had abundant defensive artillery and batteries on the river, to prevent enemy ships from crossing in front of them. The Humaitá Fortress was the most powerful and was located on high ravines, facing a very pronounced bend in the river, which forced ships to pass slowly and carefully under enemy fire. In addition, the river had been blocked by a very thick chain boom, supported by a row of small boats, which forced enemy ships to stop under enemy fire for hours to cut the chain. Artillery pieces and arsenals were located under the embankments, so that they were not within reach by enemy artillery fire.[12]

Two important forts were added to the coastal fortresses, those of Curuzú, on the coast, and Tuyú Cué. There were also long lines of trenches some distance in front of each of these fortifications, partially hidden by vegetation, which made operations difficult.[12]

The military operations corresponding to this long phase of the war took place, without exception, within this reduced area of no more than 500 square kilometers.

Tuyutí and other battles

On 24 May 1866, the battle of Tuyutí took place. With the allied army setting camp in the potrero of Tuyutí, López responded with a combined attack with most of his available troops, divided into four columns. The plan could have succeeded in conditions of numerical superiority, but the Paraguayan chief assigned to the operation little more than half the troops of the allied army he had to face. Although initially the surprise attack was successful, one of the columns took too long to join the attack, giving the allied divisions time to counterattack, which they did with complete success thanks to their superiority in weapons. Due to the tenacity of the Paraguayans, who refused to back down even when it was clear that they were being defeated, the battle resulted in the slaughter of around 6,000 Paraguayan soldiers,[18] It was the bloodiest battle in the history of South America.[12]

Despite the great victory obtained, general Mitre continued to simply wait, giving López time to gather new contingents of soldiers. However, the new recruits were mostly teenagers and old men, who did not replace in quantity or quality the casualties suffered so far.

Months later, the battle of Boquerón and the battles of Yataytí Corá, Sauce and Palmar took place in the same area.[19]

From Curuzú to Curupayty

The Brazilian forces went on the offensive without Argentine or Uruguayan participation, landing near the Curuzú Fortress, which was captured on 3 September 1866.[20]

On 12 September 1866, marshal López met in Yataytí Corá with general Mitre in search of a peaceful settlement, but the meeting was unsuccessful due to the absolute opposition of Brazil to making peace with Paraguay without a total surrender of the same. Mitre, like the Uruguayan Flores, was committed to Brazil by the secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance, signed on 1 May 1865, not to sign any separate treaty with Paraguay. However, it is known that copies of this "secret treaty" were already circulating in Europe at that time.

After the failure of the negotiations, Mitre decided to imitate the victory at Curuzú and attack the Curupayty Fortress. The prevailing bad weather gave the Paraguayans the opportunity to reinforce the defenses, and also forced the attackers to fight through flooded marshes. The Brazilian fleet, under the command of the Viscount of Tamandaré had promised to destroy the Paraguayan fortifications with its artillery from the Paraguay River, but the bombardment was carried out very ineffectively.

On 22 September 1866, the battle of Curupayty or Curupaytí took place, in which the attack of the allied forces was completely frustrated by the Paraguayan troops under the command of José E. Díaz. The Argentine and Brazilian troops, believing that the Paraguayan artillery had already been dismantled after the naval bombardment, advanced resolutely and almost unaware across the fields, being practically swept away by the same artillery that they considered to be in disarray.[21] The Argentines suffered 983 dead and 2,002 wounded; the Brazilians, 408 dead and 1,338 wounded. The Paraguayans had 92 casualties in total, between dead and wounded.[12]

Stagnation

The defeat of Curupayty stopped the actions of the allies for many months, more by the Argentines than by the Brazilian forces.[22] General Flores returned to Uruguay, leaving only 700 Uruguayan soldiers on the front under general Gregorio Suárez, who was soon replaced by Enrique Castro.[12]

The Brazilian generals argued amongst themselves, all blaming Mitre for the defeat. They asked the Emperor to demand that Mitre return to Buenos Aires, which he refused to do. In December, due to the

In March 1867, before the campaign had resumed, a cholera epidemic broke out that was brought by the Brazilian soldiers. It claimed the lives of 4,000 Brazilians, and spread through the cities and fields of Argentina and Paraguay.[23] The Argentine army also suffered many casualties, including notable officers such as general Cesáreo Domínguez. The Paraguayan civilian population, hitherto unharmed directly by the war, was terribly affected by the plague.

In the first months of that year, Brazilian forces attempted to invade occupied Paraguayan territory from Mato Grosso, which had only been partially reconquered. Epidemics and the effective action of the Paraguayan cavalry made the attempt fail. The city of Corumbá was reconquered, but abandoned a few days later, in the face of a smallpox epidemic.[24]

Capture of Tuyú Cué and Curupayty

Finally at the end of July, the Brazilian troops, commanded by Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, then Marquis of Caxias, left Tuyutí for the Tuyú Cué fortress, which was captured without a fight on the last day of that month. Up to the end of October, six other minor battles took place.[12]

While Mitre assumed command again, a Brazilian naval squadron overcame the Curupayty cannons, but remained anchored between the fortress and Humaitá for six months, forcing the construction of a railway line through the Chaco to supply it.[12][25]

On August 3, Mitre sent general Castro on a reconnaissance mission to the east and north of Humaitá. He managed to cut López's telegraphic communications at several points, and recognized the route to Tahy and a place that he mistakenly called Cierva Redoubt. The latter was an estancia, a livestock deposit for the Paraguayans to feed on and it was located on the Laguna Cierva and not on the Paraguay River as Castro believed. Despite the inaccuracy of some of his reports, other data obtained was key: the enormous number of fortifications built by López to the south and southeast of Humaitá, the "Cuadrilátero" couldn't be attacked without serious losses.

Nonetheless, Brazilian forces managed to take Tahy on November 2, cutting off Humaitá by land.[26]

On November 3, the second Battle of Tuyutí took place which resulted in a defeat for the Paraguayans, but allowed them to re-supply and capture some cannons.[27]

On 2 January 1868, Argentine Vice President Marcos Paz died in Buenos Aires from cholera and Mitre definitively abandoned the front. The supreme command of the allied army remained in the hands of the Marquis of Caxias, who was able to carry out his strategy without problems.

Capture of Humaitá

In January 1868, the cannons of the Brazilian ships had caused serious damage to the chains that crossed the river in front of Humaitá. Two of the boats that held them were sunk, leaving the chain partially submerged. At the beginning of February, with a large rise in the river level, the chains were completely submerged.

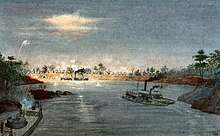

It was the opportunity that the Imperial Brazilian Navy had waited for almost two years with the squadron reinforced by three monitors that were small and fully armed being ideal for the type of maneuvers that Humaitá's position required. On February 19, after a heavy artillery exchange, some Brazilian ironclads were able to cross in front of the Humaitá fortress and three days later, two of them briefly bombarded Asunción, the city was then evacuated.[28]

The fortresses had been captured due to being evacuated by its defenders and López evacuating Humaitá Fortress through the Chaco, settling in San Fernando, a little north of the Tebicuary River.

The Humaitá Fortress was defended by only 3,000 men. The Marquis of Caxias sent a division commanded by general Manuel Luís Osório to capture the fortress, but this attack was repelled on July 16 with more than a thousand Brazilian casualties against less than a hundred Paraguayans dead. Two days later, the troops of the Argentine colonel Miguel Martínez de Hoz were ambushed in Acayuazá by the Paraguayans, who killed Martínez de Hoz and 64 of his men.[29]

On July 24, the Humaitá was evacuated by its defenders by canoe. However, only about a thousand men managed to reach Paraguayan territory as around 1,300 were taken prisoner on August 5, and the rest were killed by Brazilian naval artillery.[30]

The Humaitá campaign had lasted almost three years, since October 1865.

Pikysyry and Cordilleras campaigns

Due to the Brazilian naval advance, President López gave up defending the Tebicuary River line, installing a defensive front much closer to Asunción, on the Pikysyry stream. The advance along the Paraguay River was prevented by a new nucleus of coastal batteries in Angostura. The Brazilian troops bypassed the defenses of Angostura by way of the Chaco Basin, and attacked the enemy positions from the rear. The Paraguayan army was defeated and López evacuated Asunción, which was occupied and sacked in January 1869. The Brazilians installed a puppet government in the capital, while López progressively retreated inland.[31]

As the Paraguayan army retreated inland, it was destroyed, and the ranks began to be filled by children and the elderly.[32] For his part, López, taken by paranoia, executed nearly 400 people on the grounds that they were conspiring against him, including his two brothers.[33]

Finally, López was surrounded and killed by Brazilian troops on 1 March 1870 in the battle of Cerro Corá, in the extreme northeast of the country.[34]

Aftermath

At the end of the war, Brazil obtained all the territories it wanted and Argentina incorporated the disputed territories that today correspond to the provinces of Misiones and Formosa.[35]

The most serious result of this war was the loss of the vast majority of the Paraguayan population, being reduced to some 116,000 survivors which were mostly women, children and the elderly, compared to the 400,000 before the war. The numbers assumed by Paraguayan historians are usually much higher in terms of initial population. The Allies also had a very high number of casualties in the campaign, with more than 100,000 Brazilian dead and around 10,000 Argentine dead.[36]

Lastly, Paraguay saw its economic prosperity destroyed and was plunged into technological, cultural, and social backwardness that lasted for years. It was forced to pay huge war reparations and take out a loan that took him many decades to pay off. Its incipient industrial development disappeared completely.[6]

References

- ^ Thompson, Jorge (1910). La Guerra del Paraguay. Buenos Aires: Ed. Juan Palumbo, p. 96. Crítica de Osvaldo Magnasio. Traducción inglés-español e introducción E. Martínez Buteler.

- ^ Beverina, Juan (1921). La guerra del Paraguay: Las operaciones de la guerra en territorio argentino y brasileño. Buenos Aires: Establecimiento Gráfico Ferrari hnos, p. 202.

- ^ ISBN 9781134899128.

- ^ Pérez Pardella, Agustín (1977). Cerro Corá. Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra, p. 39

- ^ "La guerra de la triple alianza contra el Paraguay aniquiló la única experiencia exitosa de desarrollo independiente". Archived from the original on March 16, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ ISBN 9505638531

- ^ "Mato Grosso: el frente olvidado de la Guerra del Paraguay, por Florencia Pagni y Fernando Cesaretti, en Editorial Histórica.arct" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-22.

- ^ La guerra de la triple alianza.

- ^ Declaración de guerra a la Argentina, en la página del Ministerio de Educación y Cultura del Paraguay.

- ISBN 950-21-0619-9

- ^ La Triple Alianza contra Paraguay. Tratado secreto de Infamia de la Guerra del Paraguay, en La Gazeta Federal.

- ^ ISBN 987-9123-36-0

- ^ Zenequelli, Crónica de una guerra, p. 96-99.

- ^ Guerra del Paraguay Primera Parte

- ^ a b Doratioto, Maldita guerra, p. 198.

- ISBN 987-556-118-5

- ^ Doratioto, Maldita guerra, p. 201-205.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 44-45.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 61-105.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 106-109.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 127-147.

- ^ Guerra del Paraguay. Segunda Parte

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 152.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 149.

- ^ Doratioto, Maldita guerra, p. 289.

- ^ Doratioto, Maldita guerra, p. 287

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 155.

- ^ Doratioto, Maldita guerra, p. 306-311.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 157-160

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 160-161.

- ^ Díaz Gavier, En tres meses en Asunción, p. 163-164.

- ^ Acosta Ñu, por Rubén Luces León, en La Rueda.com.

- ^ "Biografía de Francisco Solano López, en Avizora publicaciones". Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Cerro Corá, la epopeya de un pueblo, por Gustavo Carrère Cadirant, en Monografías.com.

- ^ Paraguay

- ^ http://remilitari.com/guias/victimario5.htm De re militari.

Bibliography

- Díaz Gavier, Mario, En tres meses en Asunción, Ed. del Boulevard, Rosario, Argentina, 2005. ISBN 987-556-118-5

- Doratioto, Francisco, Maldita Guerra. Nueva Historia de la Guerra del Paraguay, Ed. Emecé, São Paulo/Buenos Aires, 2008, p. 30-35. ISBN 978-950-04-2574-2

- León Pomer, La guerra del Paraguay, Ed. Leviatán, Bs. As., 2008. [ISBN missing]

- ISBN 950-614-362-5

- Ruiz Moreno, Isidoro J., Campañas militares argentinas, Tomo IV, Ed. Emecé, Bs. As., 2008. ISBN 978-950-620-257-6

- Zenequelli, Lilia, Crónica de una guerra, La Triple Alianza, Ed. Dunken, Bs. As., 1997. ISBN 987-9123-36-0

Further reading

- «La Guerra del Paraguay (Visión Argentina)», en LaGazeta.com.ar.

- «La guerra de la Triple Alianza en la literatura paraguaya», en NuevoMundo.revues.org.

- Fotos de la guerra de 1870, en Meucat.com.

- «La Guerra de la Triple Alianza», en ElHistoriador.com.ar.

- «South American Military History», en Reocities.com.

- Mapa de la Guerra de la Triple Alianza.