Illinois in the American Civil War

|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

|

During the

The state was energetically led throughout the war by Governor

However, not everyone in the state supported the war. In fact, there were even calls for secession in Southern Illinois or

Eighteen counties of southern Illinois formed the congressional district of Democrat

History

During the Civil War, 256,297 people from Illinois served in the Union army, more than any other northern state except for

Union home-front support

The Chicago city government and voluntary societies gave generous support to soldiers during the war.[7] Composer and music publisher

War politics

During the

Confederate Homefront support

Copperheads

Opposition views of the Peace Democrats (or "

Notable leaders from Illinois

-

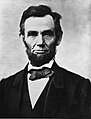

Pres.

Abraham Lincoln -

Lt. Gen.

Ulysses S. Grant -

Gov.Richard Yates

-

Sen.

Lyman Trumbull -

Maj. Gen.

John Buford -

Maj. Gen.John Pope

-

Maj. Gen.

John M. Schofield -

Maj. Gen.

John A. Logan -

Maj. Gen.John A. McClernand

-

Maj. Gen.

Benjamin Grierson -

Maj. Gen.

Stephen A. Hurlbut -

Maj. Gen.

Benjamin Prentiss -

Maj. Gen.Richard J. Oglesby

-

Bvt. Maj. Gen

Elias Smith Dennis -

Bvt. Maj. Gen

John Aaron Rawlins -

Brig. Gen.W.H.L. Wallace

-

Brig. Gen.

Elon J. Farnsworth

Among the many Illinois generals who rose to post-war prominence were

A number of soldiers from Illinois regiments would eventually become governors of U.S. states. Among them were

See also

- List of Illinois Civil War Units

- Bibliography of the American Civil War

- Bibliography of Abraham Lincoln

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

- William R. Rowley, aide-de-camp on General Grant's staff

References

- Cole, Arthur Charles, The Era of the Civil War, 1848–1870, (Sesquicentennial History of Illinois, Vol 3) (ISBN 0-252-01339-5) (1919, reprinted 1987), outstanding scholarly history covering politics, economy and society.

- Hicken, Victor, Illinois in the Civil War, University of Illinois Press, 1991, a scholarly history focused on the soldiers.

- Illinois in the Civil War. Retrieved February 1, 2005.

- Chicago History. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- Northern Illinois University's Illinois During the Civil War website. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- Leip, David. "1860 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

- Leip, David. "1864 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

Notes

- ^ Metcalf, Frank. "The Illinois Confederate Company," Confederate Veteran, vol. 16, pp.224-5. S.A. Cunningham, 1908.

- ^ 15th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry - Company G, The Confederate Army's Southern Illinois Company, Illinois in the Civil War website

- ^ William S. Morris; et al. (1998). History 31st Regiment Illinois Volunteers Organized by John A. Logan. SIU Press. pp. 15–20.

- ^ James Pickett Jones (1995). Black Jack: John A. Logan and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era. SIU Press. pp. 82–90.

- ^ "The Civil War and Late 19th Century" Archived 2012-02-23 at the Wayback Machine, The History of Southern Illinois, Egyptian Area on Aging, Inc., 1996–2009, accessed 15 May 2009

- ^ Illinois regiments during the Civil War Archived 2005-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kurt A. Carlson, "Backing the Boys in the Civil War: Chicago's Home Front Supports the Troops - and Grows in the Process," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Spring/Summer 2011, Vol. 104 Issue 1/2, pp 140-165

- ^ Leip, 1860

- ^ Bruce S. Allardice, "'Illinois is Rotten with Traitors!' The Republican Defeat in the 1862 State Election," . Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Spring/Summer 2011, Vol. 104 Issue 1/2, pp 97-114

- ^ Leip, 1864

- ^ Chicago History website

- ^ Peter J. Barry, "Amos Green, Paris, Illinois: Civil War Lawyer, Editorialist, and Copperhead," Journal of Illinois History, Spring 2008, Vol. 11 Issue 1, pp 39-60

Further reading

- Allardice, Bruce S. “‘Illinois is Rotten with Traitors!’ The Republican Defeat in the 1862 State Election,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 104 (Spring–Summer 2011), 97–114.

- Baker, Jason B. Chicago to Appomattox: The 39th Illinois Infantry in the Civil War (McFarland, 2022).

- Bearden-White, Christina. "Illinois Germans and the Coming of the Civil War: Reshaping Ethnic Identity" Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 109#3 (2016), pp. 231–251 DOI: 10.5406/jillistathistsoc.109.3.0231

- Bohn, Roger E. "Richard Yates: An Appraisal of his Value as the Civil War Governor of Illinois," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society Spring/Summer2011, Vol. 104 Issue 1/2, pp 17–37 in JSTOR

- Cole, Arthur Charles. The Era of the Civil War 1848–1870 (1919), the standard scholarly history; vol 3 of the Centennial History of Illinois.

- Costigan, David. A city in wartime: Quincy, Illinois and the Civil War (2021).

- Duerkes, Wayne N. "'I for one am ready to do my part': The initial motivations that inspired men from Northern Illinois to enlist in the U.S. Army, 1861–1862," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (2012) 105#4 pp 313–32 in JSTOR

- Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. 3 volumes. Thomas Yoseloff, reprinted 1959; covers every state

- Girardi, Robert I. "'I am for the President's Proclamation teeth and toe nails': Illinois Soldiers Respond to the Emancipation Proclamation." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 106#3-4 (2013) pp: 395–421. in JSTOR

- Gleeson, Ed. Illinois Rebels - A Civil War Unit History of G Company, 15th Tennessee Regiment Volunteer Infantry (1996, Guild Press of Indiana: Carmel, Indiana)

- Grossman, James R.. Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L. Reiff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Chicago (2005) online version

- Hicken, Victor, Illinois in the Civil War, University of Illinois Press. 1991. ISBN 0-252-06165-9.

- Jones, James Pickett (1995). Black Jack: John A. Logan and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era. SIU Press. p. 91ff.

- Jordan, Brian Matthew. Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War (WW Norton & Company, 2015)

- Karamanski, Theodore J., Rally 'Round the Flag: Chicago and the Civil War. Nelson-Hall, 1993. ISBN 0-8304-1295-6.

- Kleen, Michael, “The Copperhead Threat in Illinois Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 105 (Spring 2012), 69–92.

- Lentz, Perry. Key Command: Ulysses S. Grant's District of Cairo (University of Missouri Press, 2006)

- Levy, George. To Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas, 1862–65. (2nd ed. 1999) excerpt and text search.

- Metcalf, Frank. "The Illinois Confederate Company," Confederate Veteran, vol. 16, pp.224-5. S.A. Cunningham, 1908.

- Miller Jr, Edward A. The Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois: The Story of the Twenty-Ninth US Colored Infantry (Univ of South Carolina Press, 2021).

- Pierce, Bessie Louise. A History of Chicago: Volume II: From Town to City 1848–1871 (1937)

- Swan, James B. Chicago's Irish Legion: The 90th Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War (Southern Illinois University Press, 2009)

Historiography and memory

- Karamanski, Theodore J. "Illinois at the High Tide: The Era of the Civil War, 1848–1870." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 111.1-2 (2018): 55–78. online

- Knoll, Jeremy. "Remembering the Fallen: The Creation of Civil War Monuments in Illinois, 1865–1929." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 114.2 (2021): 33–95.

Primary sources

- Burton, William L., Descriptive bibliography of Civil War manuscripts in Illinois. Civil War Centennial Commission of Illinois, Northwestern University Press, 1966.

- Flotow, Mark, ed. In Their Letters, in Their Words: Illinois Civil War Soldiers Write Home (Southern Illinois University Press, 2019).

- Office of the Adjutant General, Roster of Officers and Enlisted Men. 9 volumes, State Printing Office, 1900.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 volumes in 4 series. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. online

- Voss-Hubbard, Mark, ed. Illinois's War: The Civil War in Documents. (Ohio University Press, 2013) 244 pp. online review

External links

- Illinois in the Civil War (Mike's Musings)

- Illinois in the Civil War (ILGenWeb Project)

- Illinois regiments during the Civil War

- History of the 77th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, W. H. Bentley, 1883

- Civil War Flags of Illinois

- [1] Illinois During the Civil War, 1861–1865, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries]

- Official Website dedicated to the memory of the 92nd Illinois Volunteer Mounted Infantry in America's Civil War Archived 2016-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- State of Illinois: 150th Civil War Anniversary project