Lactarius indigo

| Lactarius indigo | |

|---|---|

| |

| The gills of L. indigo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Russulales |

| Family: | Russulaceae |

| Genus: | Lactarius |

| Species: | L. indigo

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lactarius indigo | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Agaricus indigo Schwein. (1822) | |

| Lactarius indigo | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is depressed | |

| Hymenium is adnate or decurrent | |

mycorrhizal | |

| Edibility is edible | |

Lactarius indigo, commonly known as the indigo milk cap, indigo milky, the indigo (or blue) lactarius, or the blue milk mushroom, is a species of

Taxonomy and nomenclature

Originally described in 1822 as Agaricus indigo by American mycologist

The gradual development of blue to violet pigmentation as one progresses from species to species is an interesting phenomenon deserving further study. The climax is reached in L. indigo which is blue throughout. L. chelidonium and its variety chelidonioides, L. paradoxus, and L. hemicyaneus may be considered as mileposts along the road to L. indigo.[7]

The

Description

Like many other mushrooms, L. indigo develops from a nodule that forms within the underground mycelium, a mass of threadlike fungal cells called hyphae that make up the bulk of the organism. Under appropriate environmental conditions of temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability, the visible reproductive structures (fruit bodies) are formed. The cap of the fruit body, measuring between 5–15 cm (2.0–5.9 in) in diameter, is initially convex and later develops a central depression; in age it becomes even more deeply depressed, becoming somewhat funnel-shaped as the edge of the cap lifts upward.[13] The margin of the cap is rolled inwards when young, but unrolls and elevates as it matures. The cap surface is indigo blue when fresh, but fades to a paler grayish- or silvery-blue, sometimes with greenish splotches. It is often zonate: marked with concentric lines that form alternating pale and darker zones, and the cap may have dark blue spots, especially towards the edge. Young caps are sticky to the touch.[14]

The flesh is pallid to bluish in color, slowly turning greenish after being exposed to air; its taste is mild to slightly acrid. The flesh of the entire mushroom is brittle, and the stem, if bent sufficiently, will snap open cleanly.[15] The latex exuded from injured tissue is indigo blue, and stains the wounded tissue greenish; like the flesh, the latex has a mild taste.[8] Lactarius indigo is noted for not producing as much latex as other Lactarius species,[16] and older specimens in particular may be too dried out to produce any latex.[17]

The gills of the mushroom range from adnate (squarely attached to the stem) to slightly decurrent (running down the length of the stem), and crowded close together. Their color is an indigo blue, becoming paler with age or staining green with damage. The stem is 2–6 cm (0.8–2.4 in) tall by 1–2.5 cm (0.4–1.0 in) thick, and the same diameter throughout or sometimes narrowed at base. Its color is indigo blue to silvery- or grayish blue. The interior of the stem is solid and firm initially, but develops a hollow with age.[9] Like the cap, it is initially sticky or slimy to the touch when young, but soon dries out.[18] Its attachment to the cap is usually in a central position, although it may also be off-center.[19] Fruit bodies of L. indigo have no distinguishable odor.[20]

L. indigo var. diminutivus (the "smaller indigo milk cap") is a smaller variant of the mushroom, with a cap diameter between 3–7 cm (1.2–2.8 in), and a stem 1.5–4.0 cm (0.6–1.6 in) long and 0.3–1.0 cm (0.1–0.4 in) thick.

Microscopic features

When viewed in mass, as in a

Similar species

The characteristic blue color of the fruiting body and the latex make this species easily recognizable. Other Lactarius species with some blue color include the "silver-blue milky" (L. paradoxus), found in eastern North America,[20] which has a grayish-blue cap when young, but it has reddish-brown to purple-brown latex and gills. L. chelidonium has a yellowish to dingy yellow-brown to bluish-gray cap and yellowish to brown latex. L. quieticolor has blue-colored flesh in the cap and orange to red-orange flesh in the base of the stem.[9] Although the blue discoloration of L. indigo is thought to be rare in the genus Lactarius, in 2007 five new species were reported from Peninsular Malaysia with bluing latex or flesh, including L. cyanescens, L. lazulinus, L. mirabilis, and two species still unnamed.[25]

Edibility

Although L. indigo is a well-known edible species, opinions vary on its desirability. For example, American mycologist

In Mexico, individuals harvest the wild mushrooms for sale at farmers' markets, typically from June to November;[12] they are considered a "second class" species for consumption.[30] L. indigo is also sold in Guatemalan markets from May to October.[31] It is one of 13 Lactarius species sold at rural markets in Yunnan in southwestern China.[32]

Chemical composition

A

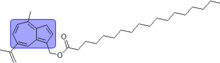

The blue color of L. indigo is due to (7-isopropenyl-4-methylazulen-1-yl)methyl stearate, an organic derivative of azulene, which is biosynthesised from a sesquiterpene very similar to matricin, the precursor for chamazulene. It is unique to this species, but similar to a compound found in L. deliciosus.[34]

Distribution, habitat, and ecology

Lactarius indigo is

L. indigo is a

Reflecting their close relationships with trees, the fruit bodies of L. indigo are typically found growing on the ground, scattered or in groups, in both

See also

References

- ^ "Russulales News Nomenclature: Lactarius indigo". The Russulales News Team. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ a b Kuntze O. (1891). Revisio Generum Plantarum (in Latin). Vol. 2. Leipzig, Germany: A. Felix. p. 857.

- ^ de Schweinitz LD. (1822). "Synopsis fungorum Carolinae superioris". Schriften der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Leipzig (in Latin). 1: 87.

- ^ Fries EM. (1836–38). Epicrisis Systematis Mycologici (in Latin). Uppsala, Sweden: Typographia Academica. p. 341.

- S2CID 27004930.

- ^ Hesler and Smith (1979), p. 66.

- ^ Hesler and Smith (1979), p. 7.

- ^ ISBN 0-8131-9039-8.

- ^ a b c d e Arora (1986), p. 69.

- ISBN 978-0-271-02891-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8117-2641-2.

- ^ a b c d e Montoya L, Bandala VM (1996). "Additional new records on Lactarius from Mexico". Mycotaxon. 57: 425–50.

- ^ Hesler and Smith (1979), p. 27.

- ISBN 0-292-72080-7.

- ISBN 0-89815-388-3.

- ^ Volk T. (2000). "Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month for June 2000". Department of Biology, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ ISBN 0-292-75125-7.

- ^ Kuo M. (March 2011). "Lactarius indigo". MushroomExpert.Com. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ Hesler and Smith (1979), pp. 68–9.

- ^ ISBN 0-7627-3109-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8156-3112-5.

- ^ Hesler and Smith (1979), p. 70.

- ^ Hesler and Smith (1979), p. 68.

- ISBN 0-916422-09-7.

- ISSN 0778-4031.

- ^ ISBN 0-7006-0571-1.

- ISBN 0-88192-586-1.

- ISBN 0-395-91090-0.

- ISBN 2-7621-2617-7.

- ISBN 978-1-887905-01-5.

- ^ S2CID 195072384.

- ^ ISSN 0253-2700.

- .

- S2CID 21207966.

- ^ Arora (1986), p. 35.

- ISSN 0972-4206.

- ^ Upadhyay RC, Kaur A (2004). "Taxonomic studies on light-spored agarics new to India". Mushroom Research. 13 (1): 1–6.

- ^ ISSN 1534-2581.

- ISBN 978-3-540-28908-1.

- ^ Winkler, D (2013). "Die erstaunliche Funga eines tropischen Bergnebel-Eichenwaldes in Kolumbien" (PDF). Der Tintling (in German). 85 (6): 27–35.

- ISBN 3-490-19818-2.

- .

- S2CID 205001566.

- ISBN 978-1-58729-627-7.

- ^ Halling RE. "Lactarius indigo (Schw.) Fries". Macrofungi of Costa Rica. The New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ISSN 0082-0598.

Cited literature

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- Hesler LR, Smith AH (1979). North American Species of Lactarius. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08440-2.

External links