Manuel Senante

Manuel Senante Martínez | |

|---|---|

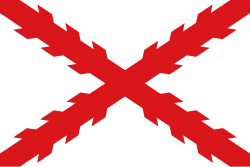

Comunión Tradicionalista |

Manuel Senante Martínez (1873–1959) was a Spanish

Family and youth

Manuel was born to a distinguished Alicantine family. His paternal grandfather, Manuel Senante Sala, was professor of Retórica y Poética at Instituto de Segunda Enseñanza of Alicante and its longtime director (1854–1889).[1] His father, Emilio Senante Llaudes (died 1916),[2] was in 1881–1909 teaching geography and history at the very same institute,[3] in 1891–1904 also serving as its director.[4] In 1907 he assumed directorship of the local Escuela Normal de Maestros.[5] Senante Llaudes wrote a number of textbooks in history, fairly popular in secondary education across Levante.[6] Apart from his educative posts, he was also active as a lawyer,[7] periodista[8] and local politician.[9] His brother Francisco Senante Llaudes was a locally recognized composer and maestro.[10]

At unspecified time Senante Llaudes married a girl from Alicante, María Teresa Martínez Torrejón (died 1885).[11] Her brother Antonio Martínez Torrejón would later become a locally known personality, deputy-mayor, poet and publisher, director of the local daily El eco de la provincia.[12] The couple had at least 3 children, Manuel born as the oldest one. His younger brother José died in infancy;[13] another one, Joaquin, perished at 16 years of age.[14]

The young Manuel was brought up in a fervently Catholic ambience;[15] in the 1890s he studied law in Barcelona and Madrid.[16] By the turn of the century, he returned to Alicante, launching his own career as a lawyer in 1897.[17] Representing his clients in cases ranging from private to commercial law,[18] he gradually grew to prominence and got engaged in politically sensitive cases, like a dispute over a forcibly closed local parish cemetery, speaking for the Alicantine San Nicolás community before the Supreme Court;[19] in 1903 he was already one of the Alicante municipal judges.[20] Manuel Senante married Josefa Esplá Rizo (1870–1957), daughter of the Alicantine merchant marine captain and also a local Alicantine municipal counselor.[21] The couple had 6 daughters (3 of them became nuns)[22] and a son, Manuel Senante Esplá, also a Carlist activist. A lawyer, in the 1930s he defended in court individuals charged with engagement in Sanjurjada.[23] He followed in the footsteps of his father and entered the publishing business, serving as member of the board of El Siglo Futuro in the 1930s;[24] during early Francoism he served as municipal judge in Madrid.[25] Senante's daughter Immaculada married Francisco Urries, catedrático of philosophy in Madrid.[26] The family initially lived at the estate of Santa Rosa in San Juan, now a bedroom suburb of Alicante;[27] in the early 20th century it moved permanently to Madrid.[28]

Early career

Senante inherited ultraconservative political outlook from his ancestors. His grandfather was a subscriber of the Carlist daily

In the early 20th century Senante dissociated himself from the conservatives and approached Partido Católico Nacional, the Integrist political party; in 1903 he was already reported by the press as “joven abogado alicantino, integrista ayer”.[37] The same year he tried his luck in elections to the Cortes, especially that according to some sources he was already one of the most influential personalities of the Right in the province.[38] He stood as a candidate of Liga Católica, a newly formed electoral platform promoted by the Church in Spain.[39] He fielded his candidature in the south-Levantine city of Orihuela,[40] but was defeated by the famous liberal politician, Francisco Ballesteros.[41]

No source consulted mentions Senante as running in the 1905 elections.[42] He engaged in setting up La Voz de Alicante, the daily which first appeared in 1904[43] and which he managed as a director.[44] The newspaper was formatted as a broad Catholic tribune, though its Integrist sympathies were evident.[45] Senante was also active in local party structures; his formal position remains unclear, but in 1906 he was already representing the provincial Integrist junta.[46] Apart from pure politics he joined a new initiative, Acción Católica, later presiding over Círculo Obrero of this organization.[47] Displaying some penchant for social issues Senante became member of Instituto de Reformas Sociales,[48] promoted also by the conservative groupings into Instituto Nacional de Previsión;[49] within this structure he entered Consejo de Patronato and represented it within employers’ associations.[50]

Deputy

Due to a chain of events following the death of

As representative of Integrism Senante was perhaps the most Right-wing, reactionary and anti-democratic deputy of the entire Cortes; even other ultraconservative MPs, the mainstream Carlists, were to a small extent prepared to demonstrate some flexibility. Senante governed his actions by the principle of defending the sacrosanct Catholic religion, which marked the most visible thread of his activity: defending rights and privileges of the Church against secularization, usually promoted by the

Having developed adopted

El Siglo Futuro

By the early 20th century Senante already had some experience as an editor, managing La Monarquia and especially La Voz de Alicante. He kept steering the Alicantine daily when the death of Ramón Nocedal vacated the chairmanship of El Siglo Futuro. The daily, set up in 1875 by Candidó Nocedal, remained a second-rate newspaper in terms of circulation and impact on the Spanish national market, but for ultraconservative politics it emerged as an iconic voice and a point of reference. Following an eight-month vacancy, in November 1907 it was Senante who appointed the new director.[64]

El Siglo Futuro remained under Senante's leadership for the next 29 years and was probably his lifetime achievement. For three decades Senante was its strategic director, editor and manager, setting the political line rather than contributing himself.

In terms of ideological outlook Senante followed the Nocedals closely; El Siglo Futuro remained an ultraconservative, vehemently anti-liberal and then anti-democratic vehicle of pursuing traditional values centered on the Catholic faith. Its principal objective was defense of religion and position of the Church; its primary foe was liberalism, later to be paired with democracy and socialism. In terms of party politics the paper remained the tribune of Integrism and was perhaps its most visible emanation in the Spanish public realm;[67] even following amalgamation within Carlism in the early 1930s El Siglo Futuro cherished its Integrist identity. In terms of its style and language El Siglo Futuro was a fairly typical Spanish party paper, excelling in bombastic, hyperbolic, inflammatory, intransigent, sectarian phraseology. The paper led a venomous campaign against the Jews and freemasonry,[68] though it did not advocate any specific measures.[69] The official Spanish digital archive describes the late daily as fanatically fundamentalist, consumed by apocalyptic obsession and dubbed “a caveman”.[70]

Dictatorship

Senante welcomed the fall of liberal democracy, deemed rotten with political corruption and unable to solve any of the problems facing the country. El Siglo Futuro greeted the coup as “el movimiento militar de Primo de Rivera, encaminado a la defensa de la realeza y del pueblo contra esta aristocracia caciquil del parlamentarismo”,

The dictatorship years witnessed major transformation of Spanish Catholicism.

El Siglo Futuro had no regrets about Primo's fall, concluding melancholically that the dictator did not live up to the vote of confidence he had received from the nation.[86] During the liberalization produced by Dictablanda, the Spanish Integrism re-emerged as a new political party, Comunión Tradicionalista-Integrista; Senante became deputy head of the entire organization[87] and signed a joint monarchist manifesto of 1930, published to defend Religion, Fatherland and Monarchy against the looming Republican threat.[88]

Republic

Senante welcomed the Republic with hardly veiled antipathy,[89] which following quema de conventos turned into horror and enmity.[90] Viewing anti-religious violence in apocalyptic terms, he advised intransigence to cardinal Segura, which in turn cost the primate expulsion from republican Spain.[91] As the two had already developed close relationship,[92] Senante engaged actively in a campaign defending the exiled primate. By the end of 1931 he clashed with the papal nuncio Tedeschini, accusing him of inaction and conspiring to get the envoy recalled to Vatican;[93] the events forged an even closer friendship between Senante and Segura.[94] In 1932 he publicly presented the doctrine of disobedience to the Republic, publishing his Cuestiones candentes de adhesión[95] and growing into a key theorist of violent resistance against the Republic.[96]

Since late 1920 Senante and the Integrists approached the

In terms of electoral tactics Senante made a U-turn. Initially he favored an alliance with the Alfonsinos and became a leading figure in Acción Nacional;[105] once the coalition assumed an accidentalist tone and got infected by Christian-democratic style he turned firmly against it,[106] growing into one of the most outspoken Carlist opponents of collaboration within either TYRE or later Bloque Nacional.[107] He was also increasingly disappointed by nationalist turn of the Basque campaign; despite his Restauración and dictatorship defense of Vascongadas fueros, Senante viewed the autonomous campaign with suspicion.[108] He tried to resume parliamentarian career not in Gipuzkoa but in his native Alicante; outmaneuvered during coalition talks he ran as independent and was defeated both in 1933[109] and 1936.[110]

In 1934 Senante successfully launched the candidature of ex-fellow Integrist

War and Francoism

It is not clear to what extent Senante participated in the Carlist plot against the Republic. During the

In 1941 he could have been involved in a plot against

None of the sources consulted provides any information on Senante's public activities after 1947; it seems that due to his age he started to withdraw from politics, still loyal to Don Javier as the Carlist regent and to Manuel Fal as the Carlist political leader. As late as in the mid-1950s in a letter to Franco he confirmed that "we, the Traditionalists" could never integrate in FET, the party founded on principles which remain unacceptable to the Communion.[132] He remained on friendly terms with the primate, cardinal Segura, especially as in the 1940s Carlism enjoyed probably best-ever relations with the Spanish Catholic hierarchy, since the 1830s at best lukewarm towards the movement.[133] Member of a number of religious associations,[134] Senante was also lawyer of the Roman Rota,[135] though his personal relations with Vatican suffered due to mutual antagonism with cardinal Tedeschini. In 1959, two weeks before death, he was applauded by the Francoist press as a nestor of Spanish journalism when awarded the hijo predilecto title by the city of Alicante.[136]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ María Dolores Mollá Soler, Instituto de Educación Secundaria Jorge Juan, [in:] Canelore. Revista del Instituto alicantino de cultura “Juan Gil-Albert”, 55 (2009), p. 239

- ^ Diario de Alicante 02.12.16, available here

- ISBN 9788436263268, p. 86. Contemporary sources claim that he was nominated professor auxiliar there in 1877, see El magisterio español, 25.06.77, available here

- ^ Mollá Soler 2009, pp. 240–241

- ISBN 9788497172424, pp. 101–102

- ^ Valls Montés 2012, pp. 113

- ^ in contemporary press he is referred to as “jurisconsulto”, El Siglo Futuro 04.12.16, available here

- ^ Joaquín Santo Matas, Treint Alicantinos al servicio de la humanidad, Alicante 2009, p. 151

- ^ the term “politico” refers probably to his service in ayuntamiento, see El Siglo Futuro 04.12.16

- ^ Ernest Llorens, Euterpe, manzana de discordia (II). Crònica del polèmic certamen d’Alacant de l’any 1889, [in:] Música i poble 172 (2013), pp. 41-42

- ^ El Nuevo Alicantino 25.07.97, available here

- ^ see e.g. El eco de la provincia 19.08.83, available here

- ^ El eco de la provincia 07.08.81, available here

- ^ El Nuevo Alicantino 25.07.97, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 04.12.16

- ISBN 9788495484802, p. 521

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ in 1914-5 he represented a party in commercial but culturally sensitive case of salterns located at the salt marshes of Elx, near terms of Sant Tomás, Carles Martín Cantareno, Ecologia i cultura: el matollar de sosa del terme Sant Tomás, un hábitat prioritari europeu vinculat al Patrimoni de la Humanitat de la Festa d’Elx, [in:] La Rella 25 (2012), pp. 97

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ “¿Quién es D. Manuel Senante? Un joven abogado alicantino, integrista ayer, autor, según se dijo, del manifesto tan íntegramenta católico que la Liga publicó al venir al mundo, y que sancionando una vez más que una cosa es predicar y otra dar trigo, solicitó y obtuvo a los pocos días del partido liberal conservador el ser nombrado juez municipal de Alicante”, La Comarca 22.6.03, available here

- ^ for an interesting piece on Anselmo Juan Esplá Rodes (1834–1918) see here

- ^ ABC 26.06.59, available here

- ISBN 9788434021099, p. 194

- ^ Eduardo González Calleja, La prensa carlista y falangista durante la Segunda República y la Guerra Civil (1931–1937), [in:] El Argonauta Espanol 9 (2012), available here, also ABC 26.06.59

- ^ El Progreso 26.04.39, available here

- ISBN 9788478485710, p. 299

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 02.01.77, available here

- ^ Larrosa, Maldonado 2012, p. 102

- ISBN 9788423532148, pp. 32-33

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez, Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ blown up in 1934 and reconstructed later, see here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 02.04.01, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 26.06.02, available here

- ^ ”Quién es D. Manuel Senante? Un joven abogado alicantino, integrista ayer, autor, según se dijo, del manifesto tan íntegramente católico que la Liga publicó al veniral mundo, y que sancionando una vez más que una cosa es predicar y otra dar trigo, solicito y obtuvo a los pocos dias del partido liberal conservador”, La Comarca 22.06.03, available here

- ^ Victoria Moreno 1984, p. 170 lists Senante along Aparisi, Mella and de Maeztu

- ^ for discussion of different phased of the strategy see Rosa Ana Gutiérrez Lloret, ¡A las urnas, en defensa de la fe! La movilización política católica en la España de comienzos del siglo XX, [in:] Pasado y Memoria 7 (2008), pp. 245–248

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez, see also El Siglo Futuro 18.07.08, available here

- ^ Senante maintained good relations with the Orihuela Jaimistas also later on, himself and de Mella visiting the city in 1911, Victoria Moreno 1984, p. 163

- ^ compare e.g. El Siglo Futuro 21.09.05, available here; Senante's name is mentioned only as he congratulated the party leader Ramón Nocedal on his triumph in Pamplona, see La Voz del Alicante 11.09.06, available here

- ^ some claim it was in 1905, see Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 27.02.06, available here; digital archive of the daily is available here

- ^ compare La Voz de Alicante 02.04.07, available here

- ^ with Emilio Pascual y Canto, see El Siglo Futuro 12.02.06, available here

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ María Gloria Redondo Rincón, El seguro obligatorio de enfermedad en España: responsables técnicos y políticos de su implantación durante el franquismo, [PhD Complutense Departamento de Farmacia y Tecnología Farmacéutica], Madrid 2013, p. 145; see also Luis Sánchez Agesta, Orígenes de la política social en la España de la Restauración, [in:] Revista de derecho político 8 (1981), p. 14

- ^ Ramón Nocedal died only 3 weeks prior to the 1907 Cortes elections. One of key party politicians, José Sánchez Marco, took Nocedal's place – virtually ensured success by means of a broad electoral alliance – in the prestigious Navarrese Pamplona district, vacating in turn his own place as an Integrist candidate in the rural Gipuzkoan district of Azpeitia; Senante became his replacement

- ^ some authors claim that Senante and other Carlist candidates owed their success in Azpeitia to Jesuit propaganda of the local Loyola sanctuary, see José Luis Orella Martínez, El origen del primer catolicismo social español [PhD thesis at Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Madrid 2012, p. 114

- ^ for 1918 see here, for 1920 see here

- ^ see the list of Integrist deputies; the Integrist leader, Juan Olazábal, preferred to stay out of Cortes and pursued his career in the regional Vascongadas politics

- ISBN 9788498831443, pp. 211–2

- Caliphate periodand intended to sell to a private antiquities dealer, triggering public debate about the piece possibly being taken out of Spain; Canalejas spoke in favor of restrictions, while Senante argued that the Church was free to handle the antique the way they liked, see J.I. Martín Benito, F. Regueras Grande, El Bote de Zamora: historia y patrimonio, [in:] De Arte 2 (2003), pp. 216-7, 221

- ^ Senante entered Academy of Basque Studies and spoke in favor of bilingualism, Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ taking turns with Manuel Chalbaud Errázquin, Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ author of a 1919 theoretical work on municipal autonomy in a regional legal ambience; he referred to “nuestras provincias Vascongadas” and spoke against municipal autonomy, considered absurd, see here Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ like in 1914, Cristóbal Robles Muñoz, Jesuitas e Iglesia Vasca. Los católicos y el partido conservador (1911–1913), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 192 (1991), p. 224

- ^ Senante inherited rhetorical skills from his father, recognised as orador, El Siglo Futuro 04.12.16

- ^ opinion of Conde de Romanones quoted after Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ISBN 9788423534371, pp. 237–238, 244

- ^ See El Siglo Futuro 06.11.07, available here

- ^ Key writers were the regular staff of Luis Ortiz y Estrada, Emilio Muñoz (Fabio), Juan Marín del Campo (Chafarote) and Felipe Robles Dégano; guest writers included important Traditionalist politicians like Conde Rodezno, José Lamamié or Manuel Fal Condé

- ^ The circulation of El Siglo Futuro was 5,000, compared to 200,000 of the monarchist ABC and 80,000 of the Catholic El Debate

- ^ El Siglo Futuro opposed militantly secular liberalism of the late Restauración, cautiously endorsed Catalan and Basque rights if framed in the traditional fueros, sympathized with the Central Powers in course of the First World War, despised the emerging anarchist and socialist Left, cheered the Primo de Rivera dictatorship to be disillusioned later, had few regrets about the fallen monarchy of Alfonso XIII but was almost explicitly hostile towards the Republic, welcomed the rise of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, to turn against the latter following the assassination of Dolfuss

- ISBN 9780521207294, p. 180. Martín Sanchez claims that El Siglo Futuro contributed to buildup of the later Francoist “crusade” propaganda by engineering anti-masonic, anti-Jewish and anti-communist mobilisation (p 87), and facilitated pro-Axis leaning by lambasting the League of Nations as steered by the Jews (84), praising Hitler and Mussolini for confronting Judaism (p. 77). On the other hand, the author ignores growing hostility of El Siglo Futuro towards the Hitlerite racism, as the daily was increasingly perturbed by “emporio del izquierdismo del razismo germánico”, see El Siglo Futuro 28.07.34, available here

- ^ Martín Sanchez 1999 does not point to any specific anti-Jewish or anti-masonic actions, advocated by El Siglo Futuro; the campaign was rather formatted as an awareness-rising exercise

- ^ See Hemeroteca Digital service available here or Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte service, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 10.10.23, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 05.10.23, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 10.09.26, available here

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez, Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ for background see Feliciano Montero García, Las derechas y el catolicismo español: del integrismo al socialcristianismo, [in:] Historia y política: Ideas, procesos y movimientos sociales 18 (2007), pp. 101–128

- ^ Robles Muñoz 1991, p. 208

- ^ the press war was waged between El Siglo Futuro and Renovación Social, the Arboleya's press tribune, Robles Muñoz 1991, p. 315

- ISBN 9788478003143, p. 184

- ISBN 9789728361365, p. 64

- ^ Segura and Senante first met in 1923 or 1924, when the latter took part in opening of the local Casa social católica, Robles Muñoz 1991, p. 140

- ^ Robles Muñoz 1991, pp. 314-5

- ^ Montero García 2008, p. 184

- ^ especially as El Debate dramatically outpaced El Siglo Futuro in terms of circulation

- ^ Senante entered Junta Central of Acción Católica in July 1931, Santiago Martínez Sánchez, El Cardenal Pedro Segura y Sáenz (1880–1957), [PhD thesis at Universidad de Navarra], Pamplona 2002, p. 176, also Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521. In November the same year he had to give way to Gil Robles, Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 207

- ISBN 9788497429054, esp. chapter "Contra el imperio de los personalismos": críticas carlistas contra Tedeschini, Herrera Oria and Vidal, pp. 165–176

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 29.01.30, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 19.03.30, available here; Senante held no functions related either to Gipuzkoa (represented by Ladislao de Zavala and others) or to Alicante (Francisco Almenar)

- ISBN 9788447201525, pp. 123–126

- ^ “hoy como ayer y como mañana y como siempre, mantenemos nuestra bandera desplegada y afirmamos el lema de nuestro programa político: «Dios, Patria, Fueros». Dentro de la monarquía católica tradicional”, see El Siglo Futuro 15.04.31, available here

- ^ “la destrucción de todo lo existente, ejército, familia, propiedad, religión, orden, hasta llegar a la guerra a Dios, al ateísmo, para hacer los hombres bestias humanas y establecer una esclavitud monstruosa y diabólica, que acabe con la obra salvadora de la civilización cristiana”, see El Siglo Futuro 12.05.31, available here

Vicente Cárcel Ortí, La persecución religiosa en España durante la Segunda República, 1931–1939, Madrid 1990, ISBN 9788432126475, p. 119

- ISBN 9788415965190, esp. the chapter Los prelados exiliados, pp. 379-431

- ^ historians refer to Senante as “amigo del Cardenal”, Robles Muñoz 1991, p. 392, or “confidente de don Pedro Segura”, Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 402

- ^ Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 203, see also Robles Muñoz 2013, pp. 661–2

- ^ for Segura the names of Senante or Fal stood for loyalty and valiance, confronted with cowardness associated with names of Herrera or Tedeschini, Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 225

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 67 claims the theory was first presented in Lerida in December 1931, Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez, claim it was in Valencia in April 1932. For the actual document, see here

- ^ “más persistente teorizador de la violencia desde el campo tradicionalista”, Eduardo González Calleja, Aproximación a las subculturas violentas de las derechas antirrepublicanas españolas (1931–1936), [in:] Pasado y Memoria 2 (2003), pp. 114–115

- ^ Antonio Manuel Moral Roncal, 1868 en la memoria carlista de 1931: dos revoluciones anticlericales y un paralelo, [in:] Hispania Sacra, 59/119 (2007), p. 355, continuing in January 1932, see also Manuel Ferrer Muñoz, Los frustrados intentos de colaboración entre el partido nacionalista vasco y la derecha navarra durante la segunda república, [in:] Principe de Viana 49 (1988), p. 131

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 325

- ISBN 9788420664552, pp. 70-71

- ^ González Calleja 2011, pp. 76-7, Blinkhorn 1975, p. 73

- ^ see El Siglo Futuro entry at the official Hispania service available here

- ^ Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, Paradójicos reaccionarios: la modernidad contra la República de la Comunión Tradicionalista, [in:] El Argonauta Espanol 9 (2012), available here; many former Integros assumed key positions within the united Carlism: apart from Senante, José Luis Zamanillo became head of paramilitary section, José Lamamié became head of the secretariat, and Manuel Fal became later political leader of the party

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 336

- ^ González Calleja 2012 claims that in 1932 the daily “volvió al redil de la Comunión y se convirtió de hecho en el órgano oficioso del partido”. However, El Siglo Futuro clarified to the readers that it was not an official Comunión Tradicionalista daily; according to the editors, the ownership transfer from Olazábal to Editorial Tradicionalista contained only one string, namely that the daily would remain Catholic when it comes ro religious question, and it would remain monarchical, antiliberal, traditionalist and antiparliamentarian when it comes to political ones, see El Siglo Futuro 20.05.33, available here

- ^ in 1931 Senante joined Acción Nacional's executive, Blinkhorn 1975, p. 52, Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez; Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ see official ministerial service here

- ISBN 9788478262663, p. 187

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez; for background see Santiago de Pablo, El carlismo guipuzcoano y el Estatuto Vasco, [in:] Bilduma Rentería 2 (1988), pp. 193–216, his also El Estatuto Vasco y la cuestión foral en Navarra durante la Segunda República, [in:] Gerónimo de Uztáriz 2 (1988), pp. 42-48

- ^ as member of Bloque Agrario Antimarxista, Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521, Blinkhorn 1975, p. 333

- ^ as “candidatura contrarrevolucionaria”, Paniagua, Piqueras 2008, p. 521

- ^ González Calleja 2011, p. 195, Blinkhorn 1975, p. 137

- ^ in 1935, when the new jefe delegado engaged fully in politics at the expense of his professional activities, Senante proposed that Fal participates in profits from his own law office or, alternatively, he gets appointed as titular director of El Siglo Futuro; both proposals were rejected, Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 256

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 208

- ^ Blinkhorn 1975, p. 215

- Luis Hernando de Larramendi, with Lamamié and Senante contributing, Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 265

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ his Madrid house was ransacked

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 311; the owner of the estate and Senante's longtime friend and collaborator, Juan Olazábal Ramery, was executed by Republican militia half a year earlier

- ^ Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 323

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ the last issue of El Siglo Futuro went to print on July 18, 1936, González Calleja 2012; the premises of the newspaper were later ransacked and taken over by the anarchist CNT militiamen

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 161

- ^ little is known about an episode of January 1941, when Senante together with Lamamié was injured in a car collision involving the Falangists; Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 298

- ^ Martínez Sánchez 2002, pp. 421–2

- ^ he accused the regime of having “llevado el desgobierno y el malestar a todos los órdenes de la Administración pública y de la vida nacional”, and which “contra toda razón y todo derecho, se ha impuesto bastardeando y contrariando los móviles que llevaron a derramar su sangre y a sufrir sacrificios de toda clase a tantos y tantos españoles”, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 240

- ISBN 9788424507077, pp. 122-3

- ^ Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 422

- ^ in February that year suggesting on behalf of Comunión Tradicionalista to nuncio Cicognani that the Spanish espiscopate should speak out against racism and totalitarianism, Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 427

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 299

- ^ though it is not clear whether he entered this body himself, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 321

- ISBN 9788475600864, pp. 356-357

- ^ see Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 412 and especially p. 572

- ^ Hermano Ministro Honorario de la V.O.T. de San Francisco el Grande, caballero del Pilar, caballero de la Santa Hermandad del Refugio, ABC 26.06.59

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Manuel Senante Martínez

- ^ ABC 13.06.59, available here

Further reading

- Cristina Barreiro Gordillo, El Carlismo y su red de prensa en la Segunda República, Madrid 2003, ISBN 9788497390378

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931–1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Eduardo González Calleja, La prensa carlista y falangista durante la Segunda República y la Guerra Civil (1931–1937), [in:] El Argonauta Espanol 9 (2012)

- Manuel Senante Martínez [in:] Javier Paniagua, José A. Piqueras (eds.), Diccionario biográfico de políticos valencianos: 1810–2006, Valencia 2008, ISBN 9788495484802

- Isabel Martín Sánchez, La campaña antimasónica en El Siglo Futuro, [in:] Historia y Comunicación Social 1999

- Santiago Martínez Sánchez, El Cardenal Pedro Segura y Sáenz (1880–1957), [PhD thesis at Universidad de Navarra], Pamplona 2002

- Antonio Manuel Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República española. Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054