Mary Sidney

Mary Herbert | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Mary Herbert (née Sidney), by Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1590. | |

| Countess of Pembroke | |

| Tenure | 19 January 1601 - 19 January 1601 |

| Known for | Literary patron, author |

| Born | 27 October 1561 Tickenhill Palace, Bewdley, England |

| Died | 25 September 1621 London, England |

| Buried | Salisbury Cathedral |

| Noble family | Sidney |

| Spouse(s) | Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke |

| Issue | William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke Katherine Herbert Anne Herbert Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke |

| Father | Henry Sidney |

| Mother | Mary Dudley |

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (

Biography

Early life

Mary Sidney was born on 27 October 1561 at

Marriage and children

In 1577, Mary Sidney married

- William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1580–1630), was the eldest son and heir.

- Katherine Herbert (1581–1584)[6] died as an infant.

- Anne Herbert (born 1583 – after 1603) was thought also to have been a writer and a storyteller.[6]

- Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke (1584–1650), succeeded his brother in 1630. Philip and his older brother William were the "incomparable pair of brethren" to whom the First Folio of Shakespeare's collected works was dedicated in 1623.

Mary Sidney was an aunt to the poet Mary Wroth, daughter of her brother Robert.

Later life

The death of Sidney's husband in 1601 left her with less financial support than she might have expected, though views on its adequacy vary; at the time the majority of an estate was left to the eldest son.

In addition to the arts, Sidney had a range of interests. She had a chemistry laboratory at Wilton House, where she developed medicines and invisible ink.[7] From 1609 to 1615, Mary Sidney probably spent most of her time at Crosby Hall in London.

She travelled with her doctor, Matthew Lister, to Spa, Belgium in 1616. Dudley Carleton met her in the company of Helene de Melun, "Countess of Berlaymont", wife of Florent de Berlaymont the governor of Luxembourg. The two women amused themselves with pistol shooting.[8] Sir John Throckmorton heard she went on to Amiens.[9] There is conjecture that she married Lister, but no evidence of this.[10]

She died of

Literary career

Wilton House

Mary Sidney turned Wilton House into a "paradise for poets", known as the "

Sidney received more dedications than any other woman of non-royal status.[13] By some accounts, King James I visited Wilton on his way to his coronation in 1603 and stayed again at Wilton following the coronation to avoid the plague. She was regarded as a muse by Daniel in his sonnet cycle "Delia", an anagram for ideal.[14]

Her brother,

Sidney psalter

Philip Sidney had completed translating 43 of the 150 Psalms at the time of his death on a military campaign against the Spanish in the

Although the psalms were not printed in her lifetime, they were extensively distributed in manuscript. There are 17 manuscripts extant today. A later engraving of Herbert shows her holding them.

Sidney was instrumental in bringing her brother's An Apology for Poetry or Defence of Poesy into print. She circulated the Sidney–Pembroke Psalter in manuscript at about the same time. This suggests a common purpose in their design. Both argued, in formally different ways, for the ethical recuperation of poetry as an instrument for moral instruction — particularly religious instruction.[19] Sidney also took on editing and publishing her brother's Arcadia, which he claimed to have written in her presence as The Countesse of Pembroke's Arcadia.[20]

Other works

Sidney's closet drama Antonius is a translation of a French play, Marc-Antoine (1578) by Robert Garnier. Mary is known to have translated two other works: A Discourse of Life and Death by Philippe de Mornay, published with Antonius in 1592, and Petrarch's The Triumph of Death, circulated in manuscript. Her original poems include the pastoral "A Dialogue betweene Two Shepheards, Thenot and Piers, in praise of Astrea,"[21] and two dedicatory addresses, one to Elizabeth I and one to her own brother Philip, contained in the Tixall manuscript copy of her verse psalter. An elegy for Philip, "The dolefull lay of Clorinda", was published in Colin Clouts Come Home Againe (1595) and attributed to Spenser and to Mary Herbert, but Pamela Coren attributes it to Spenser, though also saying that Mary's poetic reputation does not suffer from loss of the attribution.[22]

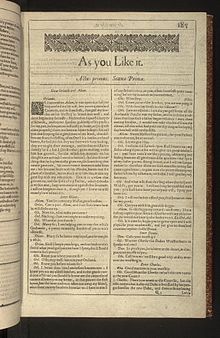

By at least 1591, the Pembrokes were providing patronage to a playing company, Pembroke's Men, one of the early companies to perform works of Shakespeare. According to one account, Shakespeare's company "The King's Men" performed at Wilton at this time.[23]

June and Paul Schlueter published an article in The Times Literary Supplement of 23 July 2010 describing a manuscript of newly discovered works by Mary Sidney Herbert.[24]

Her poetic epitaph, ascribed to Ben Jonson but more likely to have been written in an earlier form by the poets William Browne and her son William, summarizes how she was regarded in her own day:[2]

Underneath this sable hearse,

Lies the subject of all verse,

Sidney's sister, Pembroke's mother.

Death, ere thou hast slain another

Fair and learned and good as she,

Time shall throw a dart at thee.

Her literary talents and aforementioned family connections to Shakespeare has caused her to be nominated as one of the many claimants named as the true author of the works of William Shakespeare in the Shakespeare authorship question.[25][26]

In popular culture

Mary Sidney appears as a character in Deborah Harkness's novel Shadow of Night, which is the second instalment of her All Souls trilogy. Sidney is portrayed by Amanda Hale in the second season of the television adaptation of the book.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Mary Sidney | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Related pages

Notes

- ^ Each portrays the lovers as "heroic victims of their own passionate excesses and remorseless destiny".Shakespeare (1990, p. 7)

References

- ^ Bodenham 1911.

- ^ a b c d e f ODNB 2008.

- ^ ODNB 2014.

- ^ ODNB 2008b.

- ^ Pugh & Crittall 1956, pp. 289–295.

- ^ a b Hannay, Kinnamon & Brennan 1998, pp. 1–93.

- ^ Williams 2006.

- ^ Margaret Hannay, 'Reconstructing the Lives of Aristocratic Englishwomen', Betty Travitsky & Adele Seef, Attending to Women in Early Modern England (University of Delaware Press, 1994), p. 49: Maurice Lee, Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 1603-1624 (Rutgers UP, 1972), p. 209.

- ^ William Shaw & G. Dyfnallt Owen, HMC 77 Viscount De L'Isle, Penshurst, vol. 5 (London, 1961), p. 245.

- ^ Britain Magazine 2017.

- ^ Aubrey & Barber 1982.

- ^ F. E. Halliday (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore: Penguin, p. 531.

- ^ a b Williams 1962.

- ^ Daniel 1592.

- ^ Martz 1954.

- ^ Donne 1599, contained in Chambers (1896).

- ^ Walpole 1806.

- ^ Mary Herbert as illustrated in Horace Walpole, A Catalogue of the Royal and Noble Authors of England, Scotland, and Ireland.[17]

- ^ Coles 2012.

- ^ Sidney 2003.

- ^ Herbert 2014.

- ^ Coren 2002.

- ^ Halliday 1977, p. 531.

- ^ Schlueter & Schlueter 2010.

- ^ Underwood, Anne. “Was the Bard a Woman?” Newsweek 28 June 2004.

- ^ Williams, Robin P. Sweet Swan of Avon: Did a Woman Write Shakespeare? Wilton Circle Press, 2006.

Sources

- Adams, Simon (2008b) [2004], "Sidney [née Dudley], Mary, Lady Sidney", doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69749 (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ISBN 9780851152066.

- Bodenham, John (1911) [1600]. Hoops, Johannes; Crawford, Charles (eds.). Belvidere, or the Garden of the Muses. Liepzig. pp. 198–228.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Britain Magazine, Natasha Foges (2017). "Mary Sidney: Countess of Pembroke and literary trailblazer". Britain Magazine | the Official Magazine of Visit Britain | Best of British History, Royal Family,Travel and Culture.

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever, ed. (1896). The Poems of John Donne. Introduction by George Saintsbury. Lawrence & Bullen/Routledge. pp. 188–190.

- Coles, Kimberly Anne (2012). "Mary (Sidney) Herbert, countess of Pembroke". In Sullivan, Garrett A; Stewart, Alan; Lemon, Rebecca; McDowell, Nicholas; Richard, Jennifer (eds.). The Encyclopedia of English Renaissance Literature. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405194495.

- Coren, Pamela (2002). "Colin Clouts come home againe | Edmund Spenser, Mary Sidney, and the doleful lay". S2CID 162410376.

- Daniel, Samuel (1592). "Delia".

- ISBN 978-0198118367.

- ISBN 978-0715603093.

- Hannay, Margaret; Kinnamon, Noel J; Brennan, Michael, eds. (1998). The Collected Works of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke. Vol. I: Poems, Translations, and Correspondence. Clarendon. OCLC 37213729.

- Hannay, Margaret Patterson (2008) [2004], "Herbert [née Sidney], Mary, countess of Pembroke", doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13040 (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- Herbert, Mary (2014) [1599]. "A dialogue betweene two shepheards, Thenot and Piers, in praise of Astrea". In Goldring, Elizabeth; Eales, Faith; Clarke, Elizabeth; Archer, Jayne Elisabeth; Heaton, Gabriel; Knight, Sarah (eds.). John Nichols's The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth I: A New Edition of the Early Modern Sources. Vol. 4: 1596–1603. Produced by ISBN 978-0199551415.

- "June and Paul Schlueter Discover Unknown Poems by Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke". Lafayette News. Lafayette College. 23 Sep 2010.

- OCLC 17701003.

- Pugh, R B; Crittall, E, eds. (1956). "Houses of Augustinian canons: Priory of Ivychurch". A History of the County of Wiltshire | British History Online. A History of the County of Wiltshire. Vol. III.

- Shakespeare, William (1990) [1607]. ISBN 978-0521272506.

- Sidney, Philip (2003) [1590 published by William Ponsonby]. The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. Transcriptions: Heinrich Oskar Sommer (1891); Risa Stephanie Bear (2003). Renascence Editions, Oregon U.

- Smith, Hallett (1946). "English Metrical Psalms in the Sixteenth Century and Their Literary Significance". JSTOR 3816008.

- Walpole, Horatio (1806). "Mary, Countess of Pembroke". A Catalogue of the Royal and Noble Authors of England, Scotland and Ireland; with Lists of Their Works. Vol. II. Enlarged and continued — Thomas Park. J Scott. pp. 198–207.

- Williams, Franklin B (1962). The literary patronesses of Renaissance England. Vol. 9. pp. 364–366. )

- Williams, Robin P (2006). Sweet Swan of Avon: Did a woman write Shakespeare?. Peachpit. ISBN 978-0321426406.

- Woudhuysen, H R (2014) [2004], "Sidney, Sir Philip", doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25522 (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

Further reading

- Clarke, Danielle (1997). "'Lover's songs shall turne to holy psalmes': Mary Sidney and the transformation of Petrarch". Modern Language Review. 92 (2). JSTOR 3734802.

- Coles, Kimberly Anne (2008). Religion, reform, and women's writing in early modern England. CUP. ISBN 978-0521880671.

- Goodrich, Jaime (2013). Faithful Translators: Authorship, Gender, and Religion in Early Modern England. Northwestern UP. ISBN 978-0810129696.

- Hamlin, Hannibal (2004). Psalm culture and early modern English literature. CUP. ISBN 978-0521037068.

- Hannay, Margaret P (1990). Philip's phoenix: Mary Sidney, countess of Pembroke. OUP. ISBN 978-0195057799.

- Lamb, Mary Ellen (1990). Gender and authorship in the Sidney circle. Wisconsin UP. ISBN 978-0299126940.

- Prescott, Anne Lake (2002). "Mary Sidney's Antonius and the ambiguities of French history". Yearbook of English Studies. 38 (1–2). S2CID 151238607.

- Quitslund, Beth (2005). "Teaching us how to sing? The peculiarity of the Sidney psalter". Sidney Journal. 23 (1–2). Faculty of English, U Cambridge: 83–110.

- Rathmell, J C A, ed. (1963). The psalms of Sir Philip Sidney and the countess of Pembroke. New York UP. ISBN 978-0814703861.

- Rienstra, Debra; Kinnamon, Noel (2002). "Circulating the Sidney–Pembroke psalter". In Justice, George L; Tinker, Nathan (eds.). Women's writing and the circulation of ideas: manuscript publication in England, 1550–1800. CUP. pp. 50–72. ISBN 978-0521808569.

- Trill, Suzanne (2010). "'In poesie the mirrois of our age': the countess of Pembroke's 'Sydnean' poetics". In Cartwright, Kent (ed.). A companion to Tudor literature. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 428–443. ISBN 978-1405154772.

- White, Micheline (2005). "Protestant Women's Writing and Congregational Psalm Singing: from the Song of the Exiled "Handmaid" (1555) to the Countess of Pembroke's Psalmes (1599)". Sidney Journal. 23 (1–2). Faculty of English, U Cambridge: 61–82.

External links

- Works by Mary Sidney at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Mary Sidney at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about Mary Sidney at Internet Archive

- "The Works of Mary (Sidney) Herbert" (for some of the original texts and Psalms), luminarium.org; accessed 27 March 2014.

- Project Continua: Biography of Mary Sidney