Medieval renaissances

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (May 2011) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The medieval renaissances were periods of cultural renewal across

The term was first used by

History of the concept

The term 'renaissance' was first used as a name for a period in medieval history in the 1830s, with the birth of medieval studies. It was coined by Jean-Jacques Ampère.

Pre-Carolingian renaissances

As Pierre Riché points out, the expression "Carolingian Renaissance" does not imply that Western Europe was barbaric or obscurantist before the Carolingian era.

Carolingian renaissance (8th and 9th centuries)

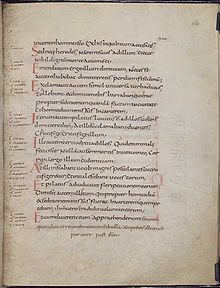

The Carolingian Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural revival in the

One of the primary efforts was the creation of a standardized curriculum for use at the recently created schools. Alcuin led this effort and was responsible for the writing of textbooks, creation of word lists, and establishing the

Art historian

Similar processes occurred in

Ottonian renaissance (10th and 11th centuries)

The Ottonian Renaissance was a limited renaissance of logic, science, economy and art in central and southern Europe that accompanied the reigns of the first three

The Ottonian Renaissance is recognized especially in the

12th-century Renaissance

The Renaissance of the 12th century was a period of many changes at the outset of the

After the collapse of the

This scenario changed during the renaissance of the 12th century. The increased contact with the

The development of medieval universities allowed them to aid materially in the translation and propagation of these texts and started a new infrastructure which was needed for scientific communities. In fact, the European university put many of these texts at the center of its curriculum,[26] with the result that the "medieval university laid far greater emphasis on science than does its modern counterpart and descendent."[27]

In Northern Europe, the

. Several Christian missionaries such asA new method of learning called scholasticism developed in the late 12th century from the rediscovery of the works of Aristotle; the works of

During the High Middle Ages in Europe, there was increased innovation in means of production, leading to economic growth. These innovations included the

See also

- Continuity thesis

- Golden Age of medieval Bulgarian culture

- Tarnovo Literary School

- Art School of Tarnovo

- Painting of the Tarnovo Artistic School

- Architecture of the Tarnovo Artistic School

References

- ^ Pierre Riché, Les Carolingiens. Une famille qui fit l'Europe, Paris, Hachette, coll. "Pluriel", 1983 p. 354

- ^ Michel Lemoine, article Arts libéraux in Claude Gauvard (dir.), Dictionnaire du Moyen Âge, Paris, PUF, coll. "Quadrige", 2002 p. 94

- ISBN 978-0230593640.

- ISBN 9780520295957.

- ^ a b Fontaine, Jacques (1959). Isidore de Séville et la culture classique dans l'Espagne wisigothique (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ISBN 9781504034692.

- ISBN 978-0853235828.

- ISBN 9783506765178.

- ^ Riché, Pierre (1995) [1962]. Éducation et culture dans l'Occident barbare (VIe-VIIIe siècles). Points Histoire (4 ed.). Paris: Le Seuil. pp. 256–257, 264, 273–274, 297.

- ^ Louis Halphen, Les Barbares, Paris, 1936, p. 236; Étienne Gilson, La Philosophie au Moyen Âge, Paris, 1944, p. 181.

- ISBN 9781438127378.

- ^ G.W. Trompf, "The concept of the Carolingian Renaissance", Journal of the History of Ideas, 1973:3ff.

- ^ John G. Contreni, "The Carolingian Renaissance", in Warren T. Treadgold, ed. Renaissances before the Renaissance: cultural revivals of late antiquity and the Middle Ages 1984:59; see also Janet L. Nelson, "On the limits of the Carolingian renaissance" in her Politics and Ritual in Early Medieval Europe, 1986.

- ISBN 978-0-06-017033-2.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (1969) Chapter One, Civilisation "By the Skin of Our Teeth".

- ^ Notably by Lynn Thorndike, as in his "Renaissance or Prenaissance?" in Journal of the History of Ideas, 4 (1943:65ff)

- ^ Scott pg 30

- ^ Cantor pg 190

- ^ Einhard's use of the Roman historian Suetonius as a model for the new genre of biography is itself a marker for the Carolingian Renaissance; see M. Innes, "The classical tradition in the Carolingian Renaissance: Ninth-century encounters with Suetonius", International Journal of the Classical Tradition, 1997.

- ISBN 978-9004168312.

- ^ Kenneth Sidwell, Reading Medieval Latin (Cambridge University Press, 1995) takes the end of Otto III's reign as the close of the Ottonian Renaissance.

- ^ (in French) P. Riché, Les Carolingiens, p. 390

- ^ P. Riché et J. Verger, Des nains sur des épaules de géants. Maîtres et élèves au Moyen Âge, Paris, Tallandier, 2006, p. 68

- ^ P. Riché et J. Verger, chapitre IV, "La Troisième Renaissance caroligienne", p. 59 sqq., chapter IV, "La Troisième Renaissance caroligienne", p.59 sqq.

- ISBN 0-89526-038-7

- ^ Toby Huff, Rise of early modern science 2nd ed. p. 180-181

- ^ Edward Grant, "Science in the Medieval University", in James M. Kittleson and Pamela J. Transue, ed., Rebirth, Reform and Resilience: Universities in Transition, 1300-1700, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1984, p. 68

- ISBN 978-0-268-01740-8.