Nicholas Roerich

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (October 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

Nicholas Roerich | |

|---|---|

| Николай Рерих | |

Naggar, Dominion of India | |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation(s) | painter, archaeologist, costume and set designer for ballets, operas, and dramas |

| Spouse | Helena Roerich |

| Children | George de Roerich, Svetoslav Roerich |

| Signature | |

| |

Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh

Born in

Biography

Early life

Raised in late-19th-century St. Petersburg, Roerich enrolled simultaneously at

Artistically, Roerich became known as his generation's most talented painter of Russia's ancient past, a topic that was compatible with his lifelong interest in archeology. He also succeeded as a stage designer by achieving his greatest fame as one of the designers for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. His best-known designs were for Alexander Borodin's Prince Igor (1909 and later productions),[6] and costumes and set for The Rite of Spring (1913),[7][8] composed by Igor Stravinsky.

Along with

Another of Roerich's artistic subjects was architecture. His acclaimed publication "Architectural Studies" (1904–1905), consisting of dozens of paintings he made of fortresses, monasteries, churches, and other monuments during two long trips through Russia, inspired his decades-long career as an activist on behalf of artistic and architectural preservation. He also designed religious art for places of worship throughout Russia and Ukraine, most notably the Queen of Heaven fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit, which the patroness Maria Tenisheva built near her Talashkino estate, and the stained glass windows for the Datsan Gunzechoinei in 1913–1915. His designs for the Talashkino church were so radical that the Orthodox church refused to consecrate the building.[9]

During the first decade of the 1900s and in the early 1910s, Roerich, largely by the influence of his wife, Helena, developed an interest in eastern religions, as well as alternative belief systems such as

The Roerichs' commitment to occult mysticism increased steadily. It was especially intense during World War I and the 1917 Russian Revolution to which the couple, like other many Russian intellectuals, accorded apocalyptic significance.[11] The influence of Theosophy, Vedanta, Buddhism, and other mystical topics can be detected not only in many of Roerich's paintings but also in the many short stories and poems that Roerich wrote before and after the 1917 revolutions, including the Flowers of Morya cycle, which was begun in 1907 and completed in 1921.

Revolution and emigration to United States

After the

Meanwhile, illness forced Roerich to leave the capital and reside in

Two unresolved historical debates are associated with Roerich's departure. First, it is often claimed that Roerich was a major candidate to direct a people's commissariat of culture (the Soviet equivalent of a ministry of culture), which the Bolsheviks considered establishing in 1917–1918, but he refused to accept the job. In fact, Benois was the most likely choice to direct any such commissariat. It seems that Roerich was a preferred choice to manage its department of artistic education; the topic is rendered moot by the fact that the Soviets elected not to establish such a commissariat.

Second, when Roerich later wished to reconcile with the Soviet Union, he maintained that he had not left Soviet Russia deliberately, but that he and his family, living in

After some months in Finland and Scandinavia, the Roerichs relocated to London, arriving in mid-1919. Engrossed with Theosophical mysticism, they now had millenarian expectations that a new age was imminent, and they wished to travel to India as soon as possible. They joined the English-Welsh chapter of the Theosophical Society. It was in London, in March 1920, that the Roerichs founded their own school of mysticism, Agni Yoga,[13] which they described as "the system of living ethics." While in London, Roerich also contributed scenic designs for LAHDA, a cooperative group of Russian theatrical artists led by Theodore Komisarjevsky.[14]

To earn passage to India, Roerich worked as a stage designer for

A successful exhibition in London resulted in an invitation from a director at the Art Institute of Chicago, offering to arrange for Roerich's art to tour the United States. In the autumn of 1920, the Roerichs traveled to America by sea.

The Roerichs remained in the United States from October 1920 until May 1923. A large exhibition of Roerich's art, organized partly by the U.S. impresario Christian Brinton and partly by the

Politically, Roerich was at first anti-Bolshevik. He gave lectures and wrote articles to White Russian populations in which he criticized the Soviet Union. However, his aversion to communism, "the impertinent monster that lies to humanity," changed in America. Roerich claimed that his spiritual masters, the "Mahatmas" in the Himalayas, were communicating telepathically with him through his wife, Helena, who was a mystic and a clairvoyant.

The beings from an

Roerichs' collaboration with Bolshevik diplomats and aim to gather intelligence on the British, led several scholars to place Nicholas Roerich as a participant in the British-Russian colonial Great Game.[16][17][18][19]

In 1923, Roerich, the "practical idealist," set out to the Himalayas with his wife and his son Yuri. Roerich initially settled in Darjeeling in the same house that the

In 1924, the Roerichs returned to the West. On his way to America, Roerich stopped at the Soviet embassy in Berlin, where he told the local plenipotentiary about a Central Asian expedition he wanted to take. He asked for Soviet protection on his way, and shared his impressions of politics in India and Tibet. Roerich commented on the "occupation of Tibet by the British" by claiming that they "infiltrate in small parties... conduct extensive anti-Soviet propaganda" by talking about "anti-religious activity of the Bolsheviks." The plenipotentiary later pointed out to one of Roerich's old university classmates, Georgy Chicherin, that he had "absolutely pro-Soviet leanings, which looked somewhat Buddho-Communistic," and that his son, who spoke 28 Asian languages, helped him in gaining the favor with the Indians and the Tibetans.[21]

The Roerichs settled in New York City, which became the base of their many American operations. They founded several institutions during these years: Cor Ardens ("Flaming Heart") and Corona Mundi ("Crown of the World"), both of which were meant to unite artists around the globe in the cause of civic activism; the Master Institute of United Arts, an art school with a versatile curriculum, and the eventual home of the first Nicholas Roerich Museum; and an American Agni Yoga Society. They also joined various theosophical societies; their activities with these groups dominated their lives.

Asian expedition (1925–1929)

After leaving New York, the Roerichs, together with their son George and six friends began the five-year Roerich Asian Expedition that in Roerich's own words "started from Sikkim through Punjab, Kashmir, Ladakh, the Karakoram Mountains, Khotan, Kashgar, Qara Shar, Urumchi, Irtysh, the Altai Mountains, the Oyrot region of Mongolia, the Central Gobi, Kansu, Tsaidam, and Tibet" with a detour through Siberia to Moscow in 1926.

The Roerichs' Asian expedition attracted attention from the foreign services and intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. In fact, prior to this expedition, Roerich had solicited the help of the Soviet government and Bolshevik secret police to assist him in his expedition by promising in return to monitor British activities in the area, but he received only a lukewarm response from Mikhail Trilisser, the chief of the Soviet foreign intelligence.

The Bolsheviks assisted Roerich with logistics while he was traveling through Siberia and Mongolia. However, they did not commit themselves to his reckless project of the Sacred Union of the East, a spiritual utopia that boiled down to Roerich's ambitious attempts to stir the Buddhist masses of inner Asia to create a highly spiritual co-operative commonwealth under the patronage of Bolshevik Russia.

The official mission of his expedition, as Roerich put it, was to act as the embassy of

Between the summer of 1927 and June 1928, the expedition was thought to have been lost, as communication with them had ceased. They had, in fact, been attacked in Tibet. Roerich wrote that only the "superiority of our firearms prevented bloodshed.... In spite of our having Tibet passports, the expedition was forcibly stopped by Tibetan authorities." They were detained by the government for five months and were forced to live in tents in sub-zero conditions and to subsist on meagre rations. Five men of the expedition died during this time. In March 1928 they were allowed to leave Tibet, and they trekked south to settle in India, where they founded a research center, the Himalayan Research Institute.

In 1929 Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the University of Paris.[25] He received two more nominations in 1932 and 1935.[26]

His concern for peace resulted in his creation of the

Manchurian expedition

In 1934–1935, the

The expedition consisted of two parts. In 1934, they explored the Greater Khingan mountains and Bargan plateau in western Manchuria. In 1935, they explored parts of Inner Mongolia: the Gobi Desert, Ordos Desert, and Helan Mountains. The expedition found almost 300 species of xerophytes, collected herbs, conducted archeological studies, and found antique manuscripts of great scientific importance.

Later life

Roerich was in India during World War II, where he painted Russian epic heroic and saintly themes, including Alexander Nevsky, The Fight of Mstislav and Rededia, and Boris and Gleb.[27]

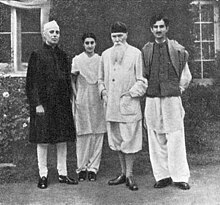

In 1942, Roerich received Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi, at his house in Kullu.[citation needed] Together they discussed the fate of the new world: "We spoke about Indian–Russian cultural association [...] it is time to think about useful and creative co-operation."[28]

Indira Gandhi would later recall several days spent together with Roerich's family: "That was a memorable visit to a surprising and gifted family where each member was a remarkable figure in himself, with a well-defined range of interests.... Roerich himself stays in my memory. He was a man with extensive knowledge and enormous experience, a man with a big heart, deeply influenced by all that he observed."

During the visit, "ideas and thoughts about closer co-operation between India and USSR were expressed. Now, after India wins independence, they have got its own real implementation[clarification needed]. And as you know, there are friendly and mutually-understanding relationships today between both our countries."[29]

In 1942, the American–Russian cultural Association (ARCA) was created in New York. Its active participants were

Roerich had a lengthy correspondence with Henry Wallace, the 1948 Progressive Party candidate for US president.

Death

Roerich died in Kullu on December 13, 1947.[31] His wife, philosopher Helena Roerich, wrote about this day: “The day of cremation was exceptionally beautiful. Not a single breath of wind and all surrounding mountains were clad in fresh snowy attire.”[32]

Cultural legacy

In the 21st century, the

Roerich's biography and his controversial expeditions to Tibet and Manchuria have been examined recently by a number of authors, including two Russians, Vladimir Rosov and Alexandre Andreyev, two Americans (Andrei Znamenski and John McCannon), and the German Ernst von Waldenfels.[35]

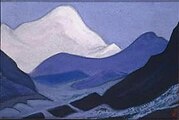

A series of his studies on the Himalayan Ranges-donated by the artist's son (36 works specifically) are even showcased in the Nicholas Roerich Gallery of the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath Museum based in Bangalore, India. The hypnotic, immersive nature of his works truly absorbs the onlooker, leaving one with a sense of peace and tranquility as one moves with the series through the gallery.

H. P. Lovecraft describes Roerich's paintings of Asian mountain landscapes as "strange and disturbing" numerous times in his Antarctic horror story At the Mountains of Madness.[36]

Roerich was awarded

In June 2013 during Russian Art Week in London, Roerich's Madonna Laboris sold at auction at Bonhams shop for £7,881,250, including the buyer's premium, making it the most valuable painting ever sold at a Russian art auction.[40]

Gallery

-

Messenger, 1897

-

Treasure of angels, 1905

-

Kiss to the Earth, 1912, scenery for Diaghilev’s The Rite of Spring ballet

-

Solveig's Song, 1912

-

Saint Olga, 1915

-

Saint Pantaleon, 1916

-

And We See, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

-

And We Are Opening the Gates, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

-

Monhegan, Maine, 1922

-

The Messenger, 1922

-

And We Are Trying, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

-

The Pigeon Book (pigeon being used as an adjective), 1922

-

Yama no Ue (Japanese, lit. 'Atop the Mountain'), from the "His Country" series, 1924

-

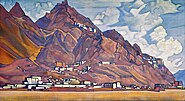

On the Way to Shelkar Dzong, 1928

-

Sunset near Shelkar, 1928

-

Shelkar Dzong, 1928

-

Madonna Protectoris, 1933

-

1933 Shelkar Dzong (fortress) and monastery

-

Sky power, 1934

-

Kampa Dzong Pink Peak, 1938

Major works

- Art and archaeology // Art and art industry. SPb., 1898. No. 3; 1899. No. 4-5.

- Some ancient Shelonsky fifths and Bezhetsky end. SPb., 31 pages, drawings of the author, 1899.

- Excursion of the Archaeological Institute in 1899 in connection with the question of the Finnish burials of St. Petersburg province. SPb., 14 p., 1900.

- Some ancient stains Derevsky and Bezhetsk. SPb., 30 p., 1903.

- In the old days, St. Petersburg., 1904,18 p., drawings of the author.

- Stone age on lake piros., SPb., ed. "Russian archaeological society", 1905.

- Collected works. kN. 1. M.: publishing house of I. D. Sytin, p. 335, 1914.

- Tales and parables. Pg.: Free art, 1916.

- Violators of Art. London, 1919.

- The Flowers Of Moria. . Berlin: Word, 128 p., Collection of poems. 1921.

- Adamant. New York: Corona Mundi, 1922

- Ways Of Blessing. New York, Paris, Riga, Harbin: Alatas, 1924

- Altai - Himalayas. (Thoughts on a horse and in a tent) 1923–1926. Ulan Bator Khoto, 1927.

- Heart of Asia. Southbury (St. Connecticut): Alatas, 1929.

- Flame in Chalice. Series X, Book 1. Songs and Sagas Series. New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1930.

- Shambhala. New York: F. A. Stokes Co., 1930

- Realm of Light. Series IX, Book II. Sayings of Eternity Series. New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1931.

- The Power Of Light. Southbury: Alatas, New York, 1931.

- Women. Address on the occasion of the opening of the Association of women, Riga, ed. About Roerich, 1931, 15 p., 1 reproduction.

- The Fiery Stronghold. Paris: World League Of Culture, 1932.

- Banner of peace. Harbin, Alatyr, 1934.

- Holy Watch. Harbin, Alatyr, 1934.

- A gateway to the Future. Riga: Uguns, 1936.

- Indestructible. Riga: Uguns, 1936.

- Roerich Essays: One hundred essays. В 2 т. India, 1937.

- Beautiful Unity. Bombey, 1946.

- Himavat: Diary Leaveves. Allahabad: Kitabistan, 1946.

- Himalayas — Adobe of Light. Bombey: Nalanda Publ, 1947.

- Diary sheets. Vol. 1 (1934-1935). M: ICR, 1995.

- Diary sheets. Vol. 2 (1936-1941). M: ICR, 1995.

- Diary sheets. Vol. 3 (1942-1947). M: ICR, 1996.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Nicholas Roerich: In Search of Shambala by Victoria Klimentieva, стр. 31

- ^ Nicholas Roerich Museum Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Andrei Znamenski, Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia, Quest Books (2011), p. 157

- ^ "Nicholas Roerich - Russian set designer". Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Nobel Prize Nomination Database

- ISBN 978-0822947417.

- New York Times, April 6, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0822947417.

- ^ ISBN 9781783743414.

- ISBN 5-86988-080-7. Page 87.

- ^ John McCannon, "Apocalypse and Tranquility: The World War I Paintings of Nicholas Roerich,” Russian History/Histoire Russe 30 (Fall 2003): 301-21

- ISBN 978-0-86565-191-3.

- ^ "Agni Yoga". highest-yoga.info. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018.

- ^ The Stage, 22 January, 1920.

- ISBN 9004129529.

- ISBN 978-90-04-27043-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8356-0891-6.

- ^ "Observer review: Tournament of Shadows by Karl Meyer and Shareen Brysac". The Guardian. January 7, 2001.

- ISBN 978-0822947417.

- ISBN 9004129529.

- ^ AVPRF, op. 04, op. 13, papka 87, d. 50117, 1. 13a. Krestinsky to Checherin, January 2, 1925

- ^ "Andrei Znamenski, "Nicholas Roerich Shambhala Warrior"". YouTube..

- ISBN 9781585092642.

- ^ "The Colorado Engineer". 1954.

- New York Times. March 3, 1929. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "Nomination Database - Peace". Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-78042-975-5. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- ISBN 5-86988-056-4

- ISBN 5-86988-148-X

- ISBN 978-0-8356-0843-5. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- ^ Madhukar, J. (October 20, 2019). "Remembering Roerich". ‘The Bangalore Mirror’. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Kamalakaran, A. (May 2, 2012). "Nicholas Roerich's legacy lives on in Himalayan Hamlet". Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "Dust throws a blanket over prized paintings". The Hindu. April 21, 2013..

- ^ "Roerich In Lahul". Roerich In Lahul. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ Nicholas Roerich: the Messenger of Zvenigorod (vol. 1: The Great Plan, vol. 2: The New Country) (2002–2004) [summary of the books in English at "Summary of Vladimir Rosovs books Nicholas Roerich. The Messenger of Zvenigorod. Website Living Ethics in the World". Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2012.]; Alexandre Andreyev, Gimalaiski mif i ego tvotry [Himalayan Myth and its Makers] (St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg University Press, 2004) [in Russian]; Andrei Znamenski, Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophesy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia (Quest Books, 2011); John McCannon, Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022) [1]; John McCannon, "Searching for Shambhala: The Mystical Art and Epic Journeys of Nikolai Roerich," Russian Life (January–February 2001); John McCannon, "By the Shores of White Waters: The Altai and Its Place in the Spiritual Geopolitics of Nicholas Roerich,” Sibirica: Journal of Siberian Studies (October 2002) [2]; Ernst von Waldenfels, Nicholas Roerich: Kunst, Macht und Okkultismus (Osburg, 2011)

- ISBN 978-0822947417.

- ^ Radulovic, Nemanja. "Rerihov pokret u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji". Godišnjak Katedre za srpsku književnost sa južnoslovenskim književnostima, XI, 2016.

- ^ "Vreme - Kultura i politika: Selidba trajne pozajmice". www.vreme.com. February 27, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "Roerich". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. NASA. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "Bonhams : Nikolai Konstantinovich Roerich (Russian, 1874-1947) Madonna Laboris". Retrieved June 14, 2016.

External links

- International Centre of the Roerichs

- International Roerich Memorial Trust (India)

- Nicholas Roerich Museum (New York)

- Estonian Roerich Society

- Roerich-movement on the Internet (in Russian)

- Paintings Gallery

- Nicholas Roerich Estate Museum in Izvara

- Roerich Family Archived March 12, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Nicholas Roerich at Find a Grave

- Catalogue of Nicholas Roerich`s works from the collection of Gorlovka Art Museum

- W.H. Crain Costume and Scene Design Collection at the Harry Ransom Center

- Nicholas Roerich Papers, J Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte

- Nicholas Roerich Lexicon

- Gallery of Russian Thinkers on Nicholas Roerich, ISFP Gallery of Russian Thinkers

- Nikolay and Svyatoslav Roerich