Nodena phase

The Nodena phase is an

The Spanish Hernando de Soto Expedition is believed to have visited several sites in the Nodena phase in the early 1540s, which is usually identified as the Province of Pacaha.[1]

Settlement pattern

Nodena phase sites are found in three geographic subdistricts: the Wilson-Joiner, the Wapanocca Lake, and the Blytheville subdistricts.

Wilson-Joiner subdistrict

- Pecan Point site (3 Ms 78) - excavated by Clarence B. Moore in 1910 or 1911[4]

Wapanocca Lake subdistrict

The largest site in the Wapanocca Lake district is the Bradley site (3 Ct 7). The Bradley Site and its nearby cluster of towns and villages (3 Ct 9, 3 Ct 43, 3 Ct 14, 3 Ct 17, Banks site) are considered good candidates for the Pacaha capital and the other nearby villages visited by the de Soto expedition.[5]

Blytheville subdistrict

- Campbell Archeological Site (23 Pm 5) - The site is in southeastern Missouri and was occupied from 1350 to 1541 CE. It features a large mound and village, as well as a cemetery area. The site was excavated by amateur archaeologist Leo O. Anderson and Professor Carl Chapman from 1954 to 1968, they published the first material on the site in 1955.[6] The site has yielded the largest number of Spanish artifacts of any prehistoric site in Southeastern Missouri. Finds at the site included glass chevron beads, a Clarksdale bell, iron knife fragments and part of a brass book binder.[7]

- Chickasawba Mound (3 M 55) - also known as the Blytheville Mound, Chickasaw Mound, Gosnell Place and the Big Mound. Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.[8]

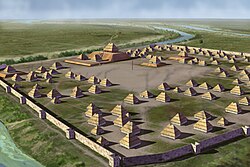

- Eaker Air Force Base near Blytheville, Arkansas that is the largest and most intact Late Mississippian Nodena phase village site within the Central Mississippi Valley.[9] It also shows evidence of later Quapaw occupation. Like many Mississippian settlements, it is located on the bank of a river, the Pemiscot Bayou in the St. Francis Basin. The Eaker site is large but has no known mound, although it is rumored to have once had one.[10]

Culture

Pottery

Most pottery found at the Nodena sites is of the Mississippian Bell Plain variety. It was buff colored, contains large fragments of ground

Lithic industry

Nodena phase peoples traded with other groups to the west and northwest in the

Nodena points are an exquisitely made willow leaf-shaped flint blades named for the Nodena site that are diagnostic of the

Agriculture and food

The people of Nodena were intensely involved in

Head deformation

The people of the Nodena phase practiced

Burial customs

Family cemeteries with burials occurring in groups of 15 to 20 or more were found at some Nodena phase sites. Burials were in the extended position, lying on their backs, with most oriented on a north–south axis. The Nodena phase people also left grave offerings for the afterlife with their deceased. Graves included a bowl and a bottle near the heads of the deceased, usually of the finer variety of effigy pottery. Sometimes tools were also included, as one woman's grave contained pottery making implements.[1]

Language

The peoples of Nodena were probably

Relationship with neighboring peoples

Other contemporaneous groups in the area include the

Other groups mentioned in the narratives were clearly vassal states of the Pacaha polity. Two such groups were the Aquixo and the Quizquiz, now identified as the Belle Meade and Walls phase peoples.[13]

Effects of European contact

De Soto encountered the Casqui tribe first. When he pressed on to visit the Pacaha, many of the Casqui people followed him. Many of the Pacaha, seeing the approach of their enemy, fled to a fortified island in the river, with many drowning in the attempt. The Casqui who had followed de Soto proceeded to sack the village, desecrate the temple and the remains of the Pacaha honored dead, and steal everything they could. Approximately one hundred and fifty Pacaha warriors were decapitated and their heads placed on poles outside the temple, replacing the heads of Casqui warriors.[13]

De Soto contacted Chief Pacaha and convinced him that he had nothing to do with the attack and that the expedition's intentions were peaceful. De Soto even assured the Pacaha that the expedition would help the Pacaha attack the Casqui to punish them for their subterfuge. The Casqui received advance warning of the planned attack and decided to return the looted items and issue an apology in order to stave off retribution from the combined Spanish and Pacaha force. De Soto arranged a dinner for the two leaders and arranged a peace treaty between the two groups. As a gesture of gratitude for the arrangement of peace and also to outdo his rival, who had only presented a daughter to de Soto, Chief Pacaha presented de Soto with one of his wives, one of his sisters, and another woman from his tribe. The de Soto expedition stayed at Pacaha's village for approximately 40 days.

The Hernando de Soto expedition records are the only historical records of Chief Pacaha and his people. Their later history remains uncertain. By the time of the next documented European presence in the area in 1673 by the Marquette and Jolliet expedition, the region was populated sparsely by the Quapaw. The introduction of European diseases such as smallpox and measles[14] and the upsetting of the local balance of power by the Spaniards is thought to have contributed to the depopulation of the region described by the de Soto expedition as the most populous they had seen in La Florida.[12]

In Aquixo, and Casqui, and Pacaha, they saw the best villages seen up to that time, better stockaded and fortified, and the people were of finer quality, excepting those of Cofitachequi.

— RODRIGO RANJEL 1547–49[15]

Attempts have been made to link the Nodena people to historic groups by analyzing words recorded in the de Soto narratives and pottery from archaeological sites. Because of their presence in the area, the Quapaw were long considered a viable candidate. More recent analysis has focused on the Tunica people, who were living in the Lower Yazoo River valley by the late 17th century.

See also

- History of the Tunica people

- Mississippian culture

- Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

- List of Mississippian sites

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

References

- ^ ISBN 1-56349-057-9.

- ^ "The Virtual Hampson Museum". Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies. University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ "Hampson Archeological Museum State Park". Archeological Collection of Nodena Artifacts. Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, Division of State Parks. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ "National Museum of the American Indian:Item detail". Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ ISBN 0-8173-0455-X.

- ^ "Campbell Site, 23PM5". Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ^ Michael John O'Brien; W. Raymond Wood (1998). The prehistory of Missouri. University of Missouri Press. p. 335.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places-Arkansas(AR)-Mississippi County". Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Program-Eaker Site". Archived from the original on 2009-08-13. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ "Archaeology at Eaker-Blytheville Research Station". Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ISBN 978-0-253-20985-6.

- ^ Hudson, Charles M.(1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- ^ a b David H. Dye (1994). "The Art of War in the Sixteenth Century Central Mississippi Valley". In Patricia B. Kwachka (ed.). Perspectives on the Southeast-Linguistics, Archaeology, Ethnohistory. University of Georgia Press.

- Charles, Hudson; Carmen Chaves, Tesser (eds.). The Forgotten Centuries-Indians and Europeans in the American South 1521 to 1704. University of Georgia Press.

- ^ "A narrative of de Soto's Expedition based on the diary of Rodrigo Ranjel". Archived from the original on 2009-03-17. Retrieved 2010-01-08.