Old Stock Americans

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

Anglo-Indians, British diaspora in Africa |

The Old Stock (also called Pioneer Stock or Colonial Stock) is a colloquial name for Americans who are descended from the original settlers of the Thirteen Colonies, especially ones who have inherited last names from that era ("Old Stock families"). Historically, Old Stock Americans have been mainly White Protestants from Northern Europe whose ancestors emigrated to British America in the 17th and 18th centuries.[2][3][4][5]

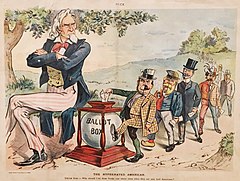

In the 19th and 20th centuries the Old Stock, especially

Settlement in the colonies

Between 1700 and 1775, the overwhelming majority of settlers to the colonies (up to 90%)[

Early European settlers

Populations of

British settlers in New England

While the majority of colonists were from

British settlers in the Old South

Conversely, in

19th to mid-20th century

Until the second half of the 20th century, the Old Stock dominated American culture and politics.[21][22]

Starting in the 1840s, millions of

American settlers arriving in the formerly Spanish or Mexican holdings of the Southwest were labelled as "Anglos".[24]

Modern day

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

See also

- Children of the American Revolution, Daughters of the American Revolution, and Sons of the Revolution

- Albion's Seed

- American ancestry

- Demographic history of the United States

- Historical racial and ethnic demographics of the United States

- History of the Puritans in North America

- Immigration to the United States

- Maps of American ancestries

- White Southerners

- Melungeons

- Nativism

- Nordicism

- The Great Gatsby

- Mountain white

- Florida cracker

- Mormon pioneers

- Anglo-Americans

References

- ^ Wilson, Bruce G. "Loyalists in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- S2CID 46298096.

- ^ Khan, Razib. "Don't count old stock Anglo-America out". Discover Magazine. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ American Baptist Historical Society (1976). Foundations. American Baptist Historical Society. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Qualey, Carlton (January 31, 2020). "Ethnicity and History". MSL Academic Endeavors. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ David Brion Davis, "Some themes of counter-subversion: an analysis of anti-Masonic, anti-Catholic, and anti-Mormon literature." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 47.2 (1960): 205–224 online.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-5839-1. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ "2.3: Immigration, Ethnicity, and the "Nadir of Race Relations"". Humanities LibreTexts. March 31, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-309-44445-3.

- OCLC 39368430.

- OCLC 17804299.

- ^ Wedin, Maud (October 2012). "Highlights of Research in Scandinavia on Forest Finns" (PDF). American-Swedish Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2017.

- ^ Lossing, B.J. (1857). Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the American Declaration of Independence. New York: Derby & Jackson. p. 112.

- Prospect Magazine. London: Prospect Publishing Ltd. Archived from the originalon September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ OCLC 727645641.

- ^ OCLC 810122408.

- ^ OCLC 167763992.

- OCLC 30892983.

- ISBN 9780742500341. Retrieved August 21, 2017 – via Google Books.

- OCLC 880122463.

- ISBN 9780549147114. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ISBN 9780739101261. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, The Protestant Crusade: 1800-1860: a study of the origins of American nativism (1938) pp. 407–436. online

- ^ "The latest to arrive were the English-speaking Americans-called “Anglos ” in New Mexico--who began moving in from the east a century ago." Neville V. Scarfe, "Testing Geographical Interest by a Visual Method." Journal of Geography 54.8 (1955): 377-387.