Pararhabdodon

| Pararhabdodon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Maxillae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Lambeosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Tsintaosaurini |

| Genus: | †Pararhabdodon Casanovas-Cladellas, Santafé-Llopis & Isidro-Llorens, 1993 |

| Type species | |

| †Pararhabdodon isonensis Casanovas-Cladellas, Santafé-Llopis & Isidro-Llorens, 1993

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Pararhabdodon (meaning "near fluted tooth" in reference to

Initially, the material was thought to belong to a

History and assigned material

Sant Romà d’Abella material

Excavation of specimens that would later be used to erect Pararhabdodon began in Spring 1985, at the Sant Romà d’Abella (SRA) locality (in the

Additional material from the type locality was collected in 1994 - including two

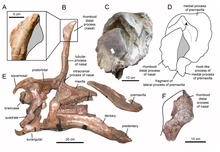

In total, known material from the type locality includes: a left and a right maxilla; five cervical, five

Referred material from other localities

In their 1997 paper, Laurent and colleagues referred remains from the Le Bexen site of the uppermost

A maxilla, specimen MCD 4919, was referred to P. isonensis in 2013. It possessed traits of the tsintaosaurin

The same 2013 study also evaluated

A hadrosaur mega-bonebed, later termed the Basturs Poble bonebed, was discovered in outcrops of the Conques Formation[c] during the late 1990s. The taxonomic status of this bonebed has fluctuated over time.[14] It has been debated whether the material represents a singular species or a combination of two distinct ones; but today a single, variable species is considered most likely.[14][15] It was suggested the material likely belong to Koutalisaurus, based on geographic proximity, but this reassignment was abandoned when that genus was recognized as indeterminate.[10][16] Since then, it has instead been tentatively assigned to the genus Pararhabdodon.[14] However, due to the lack of any suitable material for comparison and the lack of tsintaosaurin characteristics in the bonebed material, it has been more recently suggested that it should instead be considered indeterminate lambeosaur material.[13] The 2020 hindlimb description allowed for distinction between Pararhabdodon and the Basturs Poble material to be solidified, with the bonebed material showing inconsistent femoral anatomy with the genus.[11]

Relationship with "Koutalisaurus"

Near the village

Evidence for this synonymy would later come in a 2009 study, from Prieto-Márquez alongside Jonathan R. Wagner. Material from Pararhabdodon, the holotype of Koutalisaurus, and material of the Chinese species

Prieto-Márquez returned again to the dentary in 2013, in a study alongside colleagues providing a review and investigation of hadrosaurs from all over Europe. Further preparation of the specimen in the time since his last study regarding it revealed the uniqueness of the dentary had been exaggerated significantly by reconstruction of the specimen when it was first prepared in the 1990s. The Tsintaosaurus specimens showing the similar condition were found to have been distorted from a similar process. Correcting for the inaccuracies, the Los Llaus dentary is indistinguishable from that of multiple lambeosaurines, and shares no particular connection to Tsintaosaurus. With this, their reasoning for assignment of the specimen to Pararhabdodon was voided, and the specimen is now considered a completely indeterminate lambeosaurine dentary.[10]

Description

Pararhabdodon would have been a

Classification

Pararhabdodon has been classified in a number of different positions within

Casanovas-Cladellas

The proposal that P. isonensis was the first known European lambeosaurine was soon challenged, however, in 2001 by Jason Head, in a study re-evaluating the status of another species,

|

|

Prieto-Márquez would return to the issue in 2009 along with Jonathan R. Wagner. They once again turned to the articulation between the maxilla and the jugal, finding this to link Pararhabdodon to the Asian lambeosaurine,

In a 2020 study describing and naming

| Hadrosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d The geologic unit has been variously divided as the Tremp Formation, composed of several units, or the Tremp Group, composed of several formations. This article will use the Tremp Group terminology throughout for consistency.

- ^ Lower Red Unit equivalent to Talarn Formation and Gray Unit equivalent to La Posa Formation under Tremp Group nomenclature

- ^ a b c d e Equivalent to part of the "Lower Red Unit" or "Lower Red Garumnian" unit under the Tremp Formation nomenclature.

- ^ Equivalent to the "Grey Unit" or "Grey Garumnian" unit under the Tremp Formation nomenclature.

Citations

- S2CID 225110719. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- S2CID 208195457.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Prieto-Marquez, A., Gaete, R., Rivas, G., Galobart, Á., and Boada, M. (2006). Hadrosauroid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Spain: Pararhabdodon isonensis revisited and Koutalisaurus kohlerorum, gen. et sp. nov. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(4): 929-943.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Casanovas, M.L, Pereda-Suberbiola, X., Santafé, J.V., and Weishampel, D.B. (1999). First lambeosaurine hadrosaurid from Europe: palaeobiogeographical implications. Geological Magazine 136(2):205-211.

- ^ a b c Casanovas, M.L, Santafé, J.S., Sanz, J.L., and Buscalioni, A.D. (1987). Arcosaurios (Crocodilia, Dinosauria) del Cretácico superior de la Conca de Tremp (Lleida, España) [Archosaurs (Crocodilia, Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Tremp Basin (Lleida, Spain)]. Estudios Geológicos. Volumen extraordinario Galve-Tremp:95-110. [Spanish]

- ^ a b Casanovas-Cladellas, M.L., Santafé-Llopis, J.V., and Isidro-Llorens, A. (1993). Pararhabdodon isonensis n. gen. n. sp. (Dinosauria). Estudio mofológico, radio-tomográfico y consideraciones biomecanicas [Pararhabdodon isonense n. gen. n. sp. (Dinosauria). Morphology, radio-tomographic study, and biomechanic considerations]. Paleontologia i Evolució 26-27:121-131. [Spanish]

- ^ a b Laurent, Y., LeLoeuff, J., & Buffetaut, E. (1997). Les Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) du Maastrichtien supérieur des Corbières orientales (Aude, France) [The Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Upper Maastrichtian of the eastern Corbières (Aude, France)]. Revue de Paléobiologie 16:411-423. [French]

- ^ a b c Casanovas-Cladellas, M. L.; Santafé-Llopis, J. V.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (1997). "New remains of Pararhabdodon isonensis (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) and a synthesis of the assemblage of material discovered in the Upper Cretaceous of Catalonia". Second Workshop of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts (Unpaginated). Espéraza-Quillan.

- ^ Casanovas-Cladellas, M. L., Santafé-Llopis, J. V., & Pereda-Suberbiola, X. (1997). Nouveaux restes de Pararhabdodon (Dinosauria, Hadrosauridae) et synthèse de l’ensemble du materiel découvert dans le Cretacé supérieur de Catalogne. In Second European Workshop of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts (unpaginated).

- ^ PMID 23922815.

- ^ S2CID 225110719.

- ^ Laurent, Y. (2002). Les faunes de vertébrés continentaux du Maastrichtien supérieur d'Europe: systématique et biodiversité (Doctoral dissertation, Toulouse 3).

- ^ S2CID 134582286.

- ^ PMID 30379888.

- .

- ^ Prieto-Márquez A, Gaete R, Galobart A, Riera V. New data on European Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the latest Cretaceous of Spain. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2007;27(3): 131A.

- ^ S2CID 85081036.

- ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- .

- S2CID 85705882.

- S2CID 228807024.