Siege of the British Residency in Kabul

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

| Siege of the British Residency in Kabul | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Anglo-Afghan War | |||||||

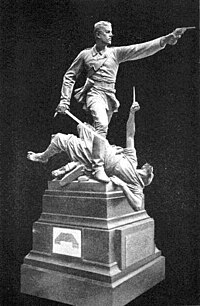

Statue of Lt Walter Hamilton, VC during the attack on the residency | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Afghan mutineers | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 75 men | 2,000+ men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 72 killed | 600 killed | ||||||

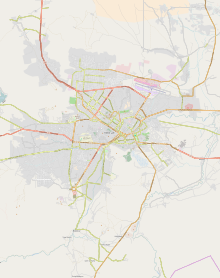

Location within Kabul | |||||||

The siege of the British Residency in Kabul was a military engagement of the

Prelude

During the second phase of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, British troops invaded Afghanistan, and forced the Amir Sher Ali Khan to flee. He was replaced by his son Mohammad Yaqub Khan, who immediately sued for peace. The resulting Treaty of Gandamak satisfied most British demands, including the annexation of several frontier districts, and the dispatch of a British envoy to Kabul to supervise Afghan foreign relations.

The

Despite his experience of the region and his qualities as a diplomat, Cavagnari's appointment was viewed with some misgivings by British observers who knew his arrogant manners. General Neville Chamberlain said of him that he was:

...more the man for facing an emergency than one to entrust with a position requiring delicacy and very calm judgement...If he were left at Cabul as our agent I should fear his not keeping us out of difficulties.[1]

In addition, as the principal negotiator of the humiliating treaty of Gandamak, Cavagnari was hated by the Afghan populace. Despite this, he was chosen by the Governor-General Lord Lytton, who trusted and appreciated him.[2]

The envoy arrived in Kabul on July 24, 1879, with his assistant, a surgeon, and an escort of 75 soldiers of the elite

Siege

In Kabul, the delegation occupied a

In the morning of September 3, the Herati regiments gathered once more inside the Bala Hissar, demanding their pay, but due to Tax revenues not having been collected, only one month's pay was offered to them. At this point someone suggested that the British had gold in their Residency, and the mutinous soldiers went to ask Cavagnari to pay their salaries. When confronted with these demands, the envoy refused to pay, claiming that the matter was of no concern to the British government. A scuffle ensued, and several shots were fired by the British troops. The Afghan soldiers immediately returned to their cantonment to fetch their weapons, while Cavagnari prepared the compound as best he could, and sent a plea for help to the Amir.

Within the hour, 2,000 Afghan soldiers returned and invaded the Residency, which proved impossible to defend. It was surrounded on three sides by taller houses, enabling the Herati troops to gain advantageous firing positions from which they opened a heavy fire that gradually wiped out the defenders. Cavagnari was the first casualty of the attack, being hit in the head by a musket ball, but he was still able to lead a bayonet charge and drive the Afghans out of the compound, after which he withdrew inside the buildings and died of his wounds.

The defense was taken over by Lieutenant Hamilton, who despatched a second messenger to Yakub Khan. This time the Amir sent his young son and a Mullah to try and pacify the mutineers, but their party was pelted with stones, unhorsed and forced to retreat. By midday, the main building of the Residency was on fire, and only 30 Guides and three British officers were fit enough to keep fighting. A last messenger was dispatched to the Amir, who answered that he was powerless to help.

Eventually, the Afghans brought two cannons to the Residency, and started firing point-blank at the building. Hamilton led his remaining men in a charge that captured one gun, but they were driven back by Afghan fire that killed the surgeon, Kelly, and six sepoys. Hamilton urged his men to charge the guns once more but Jenkyns, Cavagnari's assistant, was killed, and the defenders were driven back. As the main building was on fire and collapsing, Hamilton and the 20 surviving sepoys took refuge in the brick bathhouse of the residency. Hamilton led another charge on the Afghan guns, and this time three sepoys managed to hitch their belts onto one of the gun carriages. After a moment's hesitation, the Herati soldiers charged the small party of Guides. Hamilton faced the oncoming Afghan wave, and emptied his revolver into them before being overwhelmed and killed. His stand allowed his 5 surviving men to retreat inside the compound.

As all the British officers were now dead, the Afghans offered the Moslem soldiers the chance to surrender, but their offer was refused by the Guides, now led by Jemadar Jewand Singh. Instead, the remaining dozen Guides charged out of the compound, where they were all killed, but not before the Jemadar had accounted for 8 Afghans. By early evening, the occupants of the Residency were dead; the siege had lasted 8 hours.

Aftermath

From the original force of four British officers and 75 Indian soldiers, only 7 soldiers survived: 4 who were away from the Residency at the time of the attack, and 3 who were sent as messengers to the Amir and detained. A British military commission formed to investigate the events expressed the opinion that "the annals of no army and no regiment can show a brighter record of bravery than has been achieved by this small band of Guides."[6] The entire escort were awarded the Indian Order of Merit (native soldiers at that time were not eligible for the Victoria Cross), and the Corps of Guides was awarded the Battle honour "Residency, Kabul".

The death of Cavagnari and the destruction of the Residency marked a turning point in the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Lytton's aggressive policy towards Afghanistan, known as the "Forward policy", destined to counter a potential

A military force, known as the

In popular culture

The siege is portrayed, with some fictionalization, in

References

Sources

- Robson, Brian. (2007). The Road to Kabul: The Second Afghan War 1878–1881. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-416-7.

- Richards, D.S. (1990). The Savage Frontier, A History of the Anglo-Afghan Wars. London: ISBN 0-330-42052-6.