Afghanistan

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

| |

|---|---|

| Motto: لا إله إلا الله، محمد رسول الله Lā ʾilāha ʾillā llāh, Muhammadun rasūlu llāh "There is no god but Shahadah) | |

| Anthem: دا د باتورانو کور "Dā Də Bātorāno Kor" "This Is the Home of the Brave"[2] | |

| Hibatullah Akhundzada | |

| Hasan Akhund (acting) | |

| Abdul Hakim Haqqani | |

| Legislature | None 27 May 1863 |

| 26 May 1879 | |

| 19 August 1919 | |

• Kingdom | 9 June 1926 |

• Republic | 17 July 1973 |

| 27–28 April 1978 | |

| 28 April 1992 | |

| 27 September 1996 | |

| 26 January 2004 | |

| 15 August 2021 | |

Afghanistan Time) | |

| DST is not observed[25] | |

| ISO 3166 code | AF |

| Internet TLD | .af |

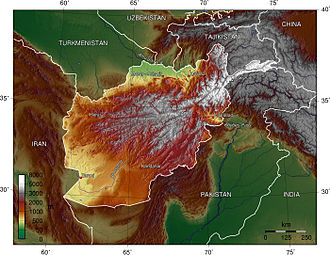

Afghanistan,[d] officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,[e] is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia,[26] it is bordered by Pakistan to the east and south,[f] Iran to the west, Turkmenistan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, Tajikistan to the northeast, and China to the northeast and east. Occupying 652,864 square kilometers (252,072 sq mi) of land, the country is predominantly mountainous with plains in the north and the southwest, which are separated by the Hindu Kush mountain range. Kabul is the country's largest city and serves as its capital. According to the World Population review, as of 2021[update], Afghanistan's population is 40.2 million.[6] The National Statistics Information Authority of Afghanistan estimated the population to be 32.9 million as of 2020[update].[28]

Since the late 1970s, Afghanistan's history has been dominated by extensive warfare, including

Afghanistan is rich in natural resources, including

Etymology

Some scholars suggest that the

Historically, the ethnonym Afghān was used to refer to ethnic

The name Afghanistan (Afghānistān, land of the Afghans / Pashtuns, afāghina, sing. afghān) can be traced to the early eighth/fourteenth century, when it designated the easternmost part of the

Kartid realm. This name was later used for certain regions in the Ṣafavid and Mughal empires that were inhabited by Afghans. While based on a state-supporting elite of Abdālī / Durrānī Afghans, the Sadūzāʾī Durrānī politythat came into being in 1160 / 1747 was not called Afghanistan in its own day. The name became a state designation only during the colonial intervention of the nineteenth century.

The term "Afghanistan" was officially used in 1855, when the British recognized Dost Mohammad Khan as king of Afghanistan.[47]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Excavations of prehistoric sites suggest that humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago, and that farming communities in the area were among the earliest in the world. An important site of early historical activities, many believe that Afghanistan compares to

After 2000 BCE, successive waves of semi-nomadic people from Central Asia began moving south into Afghanistan; among them were many

During the first century BCE, the

Medieval period

By the 11th century,

In 1219 CE,

In the early 16th century,

Hotak Dynasty

In 1709,

In 1738, Nader Shah and his forces captured Kandahar in the siege of Kandahar, the last Hotak stronghold, from Shah Hussain Hotak. Soon after, the Persian and Afghan forces invaded India, Nader Shah had plundered Delhi, alongside his 16-year-old commander, Ahmad Shah Durrani who had assisted him on these campaigns. Nader Shah was assassinated in 1747.[94][95]

Durrani Empire

After the death of Nader Shah in 1747,

Ahmad Shah

Ahmad Shah Durrani died in October 1772, and a civil war over succession followed, with his named successor, Timur Shah Durrani succeeding him after the defeat of his brother, Suleiman Mirza.[101] Timur Shah Durrani ascended to the throne in November 1772, having defeated a coalition under Shah Wali Khan and Humayun Mirza. Timur Shah began his reign by consolidating power toward himself and people loyal to him, purging Durrani Sardars and influential tribal leaders in Kabul and Kandahar. One of Timur Shah's reforms was to move the capital of the Durrani Empire from Kandahar to Kabul. Timur Shah fought multiple series of rebellions to consolidate the empire, and he also led campaigns into Punjab against the Sikhs like his father, though more successfully. The most prominent example of his battles during this campaign was when he led his forces under Zangi Khan Durrani – with over 18,000 men total of Afghan, Qizilbash, and Mongol cavalrymen – against over 60,000 Sikh men. The Sikhs lost over 30,000 in this battle and staged a Durrani resurgence in the Punjab region[102] The Durranis lost Multan in 1772 after Ahmad Shah's death. Following this victory by Timur Shah, Timur Shah was able to lay siege to Multan and recapture it,[103] incorporating it into the Durrani Empire once again, reintegrating it as a province until the Siege of Multan (1818). Timur Shah was succeeded by his son Zaman Shah Durrani after his death on in May 1793. Timur Shah's reign oversaw the attempted stabilization and consolidation of the empire. However, Timur Shah had over 24 sons, which plunged the empire in civil war over succession crises.[104]

Barakzai dynasty and British wars

By the early 19th century, the Afghan empire was under threat from the

With the collapse of the Durrani Empire, and the exile of the

In 1839, a

Dost Mohammad died in June 1863, a few weeks after his successful

How can a small power like Afghanistan, which is like a goat between these lions [Britain and Russia] or a grain of wheat between two strong millstones of the grinding mill, stand in the midway of the stones without being ground to dust?

During the

After the end of the Third Anglo-Afghan War and the signing of the

Some of the reforms that were put in place, such as the abolition of the traditional

Until 1946, King Zahir ruled with the assistance of his uncle, who held the post of

Zahir Shah, like his father Nadir Shah, had a policy of maintaining national independence while pursuing gradual modernization, creating nationalist feeling, and improving relations with the United Kingdom. Afghanistan was neither a participant in

Democratic Republic and Soviet war

In April 1978, the communist

In September 1979, PDPA General Secretary Taraki was assassinated in an internal coup orchestrated by then-prime minister

The Soviet-Afghan War had drastic social effects on Afghanistan. The

Post–Cold War conflict

Another civil war broke out after the

After the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum formed the Northern Alliance, later joined by others, to resist the Taliban. Dostum's forces were defeated by the Taliban during the Battles of Mazar-i-Sharif in 1997 and 1998; Pakistan's Chief of Army Staff, Pervez Musharraf, began sending thousands of Pakistanis to help the Taliban defeat the Northern Alliance.[173][161][174][175][176][excessive citations] By 2000, the Northern Alliance only controlled 10% of territory, cornered in the northeast. On 9 September 2001, Massoud was assassinated by two Arab suicide attackers in Panjshir Valley. Around 400,000 Afghans died in internal conflicts between 1990 and 2001.[177]

US invasion and Islamic Republic

In October 2001, the United States invaded Afghanistan to remove the Taliban from power after they refused to hand over Osama bin Laden, the prime suspect of the September 11 attacks, who was a "guest" of the Taliban and was operating his al-Qaeda network in Afghanistan.[178][179][180] The majority of Afghans supported the American invasion.[181][182] During the initial invasion, US and UK forces bombed al-Qaeda training camps, and later working with the Northern Alliance, the Taliban regime came to an end.[183]

In December 2001, after the Taliban government was overthrown, the

The Afghan government was able to build some democratic structures, adopting a constitution in 2004 with the name

On 19 February 2020, the

Second Taliban era

NATO Secretary General

According to the Costs of War Project, 176,000 people were killed in the conflict, including 46,319 civilians, between 2001 and 2021.[222] According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, at least 212,191 people were killed in the conflict.[223] Though the state of war in the country ended in 2021, armed conflict persists in some regions[224][225][226] amid fighting between the Taliban and the local branch of the Islamic State, as well as an anti-Taliban Republican insurgency.[227]

The Taliban government is led by

Western nations suspended most of their humanitarian aid to Afghanistan following the Taliban's August 2021 takeover of the country; the World Bank and International Monetary Fund also halted their payments.[236][237] More than half of Afghanistan's 39 million people faced an acute food shortage in October 2021.[238] Human Rights Watch reported on 11 November 2021 that Afghanistan was facing widespread famine due to an economic and banking crisis.[239] The Taliban have significantly tackled corruption, now being placed as 150th on the corruption watchdog perception index. The Taliban have also reportedly reduced bribery and extortion in public service areas.[240] At the same time, the human rights situation in the country has deteriorated.[241] Following the 2001 invasion, more than 5.7 million refugees returned to Afghanistan;[242] however, in 2021, 2.6 million Afghans remained refugees, primarily in Iran and Pakistan, and another 4 million were internally displaced.[243]

In October 2023, the Pakistani government ordered the

Geography

Afghanistan is located in Southern-Central Asia.

Asia is a body of water and earth, of which the Afghan nation is the heart. From its discord, the discord of Asia; and from its accord, the accord of Asia.

At over 652,864 km2 (252,072 sq mi),

The geography in Afghanistan is varied, but is mostly mountainous and rugged, with some unusual mountain ridges accompanied by plateaus and river basins.

Despite having numerous rivers and

The northeastern Hindu Kush

Climate

Afghanistan has a

Biodiversity

Several types of

The forest region of Afghanistan has vegetation such as

Demographics

The population of Afghanistan was estimated at 32.9 million as of 2019 by the Afghanistan Statistics and Information Authority,[279] whereas the UN estimates over 38.0 million.[280] In 1979 the total population was reported to be about 15.5 million.[281] About 23.9% of them are urbanite, 71.4% live in rural areas, and the remaining 4.7% are nomadic.[282] An additional 3 million or so Afghans are temporarily housed in neighboring Pakistan and Iran, most of whom were born and raised in those two countries. As of 2013, Afghanistan was the largest refugee-producing country in the world, a title held for 32 years.

The current population growth rate is 2.37%,[20] one of the highest in the world outside of Africa. This population is expected to reach 82 million by 2050 if current population trends continue.[283] The population of Afghanistan increased steadily until the 1980s, when civil war caused millions to flee to other countries such as Pakistan.[284] Millions have since returned and the war conditions contribute to the country having the highest fertility rate outside Africa.[285] Afghanistan's healthcare has recovered since the turn of the century, causing falls in infant mortality and increases in life expectancy, although it has the lowest life expectance of any country outside Africa. This (along with other factors such as returning refugees) caused rapid population growth in the 2000s that has only recently started to slow down.[citation needed] The Gini coefficient in 2008 was 27.8.[286]

Ethnicity and languages

When it comes to foreign languages among the populace, many are able to speak or understand

Religion

The CIA estimated in 2009 that 99.7% of the Afghan population was Muslim

Afghan Sikhs and Hindus are also found in certain major cities (namely Kabul, Jalalabad, Ghazni, Kandahar)[298][299] accompanied by gurdwaras and mandirs.[300] According to Deutsche Welle in September 2021, 250 remain in the country after 67 were evacuated to India.[301]

There was a small Jewish community in Afghanistan, living mainly in Herat and Kabul. Over the years, this small community was forced to leave due to decades of warfare and religious persecution. By the end of the twentieth century, nearly the entire community had emigrated to Israel and the United States, with one known exception, Herat-born Zablon Simintov. He remained for years, being the caretaker of the only remaining Afghan synagogue. He left the country for the US after the second Taliban takeover. A woman who left shortly after him has since been identified as the likely last Jew in Afghanistan.[302][303][304]

Urbanization

As estimated by the CIA World Factbook, 26% of the population was urbanized as of 2020. This is one of the lowest figures in the world; in Asia it is only higher than Cambodia, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Urbanization has increased rapidly, particularly in the capital Kabul, due to returning refugees from Pakistan and Iran after 2001, internally displaced people, and rural migrants.[307] Urbanization in Afghanistan is different from typical urbanization in that it is centered on just a few cities.[308]

The only city with over a million residents is its capital, Kabul, located in the east of the country. The other large cities are located generally in the "ring" around the Central Highlands, namely Kandahar in the south, Herat in the west, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kunduz in the north, and Jalalabad in the east.[282]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kabul  Kandahar |

1 | Kabul | Kabul Province | 4,273,200 |  Herat  Mazar-i-Sharif | ||||

| 2 | Kandahar | Kandahar Province | 614,300 | ||||||

| 3 | Herat | Herat Province | 556,200 | ||||||

| 4 | Mazar-i-Sharif | Balkh Province | 469,200 | ||||||

| 5 | Jalalabad | Nangarhar Province | 356,500 | ||||||

| 6 | Kunduz | Kunduz Province | 263,200 | ||||||

| 7 | Taloqan | Takhar Province | 253,700 | ||||||

| 8 | Puli Khumri | Baghlan Province | 237,900 | ||||||

| 9 | Ghazni | Ghazni Province | 183,000 | ||||||

| 10 | Khost | Khost Province | 153,300 | ||||||

Education

The top universities in Afghanistan are the

After the Taliban regained power in 2021, it became unclear to what extent female education would continue in the country. In March 2022, after they had been closed for some time, it was announced that secondary education would be reopened shortly. However, shortly before reopening, the order was rescinded and schools for older girls remained closed.[315] Despite the ban, six provinces, Balkh, Kunduz, Jowzjan, Sar-I-Pul, Faryab, and the Day Kundi, still allow girl's schools from grade 6 and up.[316][317] In December 2023, investigations were being held by the United Nations on the claim that Afghan girls of all ages were allowed to study at religious schools.[318]

Health

According to the

There are over 100

It was reported in 2006 that nearly 60% of the Afghan population lives within a two-hour walk of the nearest health facility.[324] The disability rate is also high in Afghanistan due to the decades of war.[325] It was reported recently that about 80,000 people are missing limbs.[326][327] Non-governmental charities such as Save the Children and Mahboba's Promise assist orphans in association with governmental structures.[328]

Governance

Following the effective collapse of the

A traditional instrument of governance in Afghanistan is the

Development of Taliban government

This section needs to be updated. (December 2023) |

On 17 August 2021, the leader of the Taliban-affiliated Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin party, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, met with both Hamid Karzai, the former President of Afghanistan, and Abdullah Abdullah, the former chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation and former Chief Executive, in Doha, Qatar, with the aim of forming a national unity government.[336][337] President Ashraf Ghani, having fled the country during the Taliban advance to either Tajikistan or Uzbekistan, emerged in the United Arab Emirates and said that he supported such negotiations and was in talks to return to Afghanistan.[338][339] Many figures within the Taliban generally agreed that continuation of the 2004 Constitution of Afghanistan may, if correctly applied, be workable as the basis for the new religious state as their objections to the former government were political, and not religious.[340]

Hours after the final flight of American troops left Kabul on 30 August, a Taliban official interviewed said that a new government would likely be announced as early as Friday 3 September after

In a report by CNN-News18, sources said the new government was going to be governed similarly to Iran with Haibatullah Akhundzada as supreme leader similar to the role of Saayid Ali Khamenei, and would be based out of Kandahar. Baradar or Yaqoob would be head of government as Prime Minister. The government's ministries and agencies will be under a cabinet presided over by the Prime Minister. The Supreme Leader would preside over an executive body known as the Supreme Council with anywhere from 11 to 72 members. Abdul Hakim Haqqani is likely to be promoted to Chief Justice. According to the report, the new government will take place within the framework of an amended 1964 Constitution of Afghanistan.[342] Government formation was delayed due to concerns about forming a broad-based government acceptable to the international community.[343] It was later added however that the Taliban's Rahbari Shura, the group's leadership council was divided between the hardline Haqqani Network and moderate Abdul Ghani Baradar over appointments needed to form an "inclusive" government. This culminated in a skirmish which led to Baradar being injured and treated in Pakistan.[344]

As of early September 2021, the Taliban were planning the Cabinet to be men-only. Journalists and other human rights activists, mostly women,

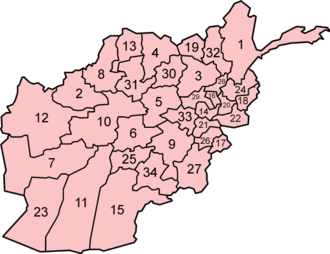

Administrative divisions

Afghanistan is administratively divided into 34 provinces (, each of which normally covers a city or several villages. Each district is represented by a district governor.

The

According to article 140 of the constitution and the presidential decree on electoral law, mayors of cities should be elected through free and direct elections for a four-year term. In practice however, mayors are appointed by the government.[349]

The 34 provinces in alphabetical order are:

Foreign relations

Afghanistan became a member of the United Nations in 1946.[350] Historically, Afghanistan had strong relations with Germany, one of the first countries to recognize Afghanistan's independence in 1919; the Soviet Union, which provided much aid and military training for Afghanistan's forces and includes the signing of a Treaty of Friendship in 1921 and 1978; and India, with which a friendship treaty was signed in 1950.[351] Relations with Pakistan have often been tense for various reasons such as the Durand Line border issue and alleged Pakistani involvement in Afghan insurgent groups.

The present Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is currently internationally

Military

The

Human rights

References

Citations

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in Geonames.org (CC BY)

- ^ a b "Population Matters". 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan's ethnic mosaic". The Times of India. 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Afghanistan Population 2021". World Population Review. 19 September 2021.

- ^ "Distribution of Afghan population by ethnic group 2020". 20 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Afghan Ethnic Groups: A Brief Investigation". 14 August 2011.

- ^ Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Reference.com (Retrieved 13 November 2007).

- ^ Dictionary.com. WordNet 3.0. Princeton University. Reference.com (Retrieved 13 November 2007). Archived 28 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Constitution of Afghanistan". 2004. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ISBN 9781107660151.

- S2CID 253945821.

Afghanistan is now controlled by a militant group that operates out of a totalitarian ideology.

- Madadi, Sayed (6 September 2022). "Dysfunctional centralization and growing fragility under Taliban rule". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

In other words, the centralized political and governance institutions of the former republic were unaccountable enough that they now comfortably accommodate the totalitarian objectives of the Taliban without giving the people any chance to resist peacefully.

- Sadr, Omar (23 March 2022). "Afghanistan's Public Intellectuals Fail to Denounce the Taliban". Fair Observer. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

The Taliban government currently installed in Afghanistan is not simply another dictatorship. By all standards, it is a totalitarian regime.

- "Dismantlement of the Taliban regime is the only way forward for Afghanistan". Atlantic Council. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

As with any other ideological movement, the Taliban's Islamic government is transformative and totalitarian in nature.

- Akbari, Farkhondeh (7 March 2022). "The Risks Facing Hazaras in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan". George Washington University. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

In the Taliban's totalitarian Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, there is no meaningful political inclusivity or representation for Hazaras at any level.

- Madadi, Sayed (6 September 2022). "Dysfunctional centralization and growing fragility under Taliban rule". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^

- Choi, Joseph (8 September 2021). "EU: Provisional Taliban government does not fulfill promises". The Hill. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- Bezhan, Frud (7 September 2021). "Key Figures In The Taliban's New Theocratic Government". Radio Farda. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- George, Susannah (18 February 2023). "Inside the Taliban campaign to forge a religious emirate". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ^ T. S. Tirumurti (26 May 2022). "Letter dated 25 May 2022 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- JURIST. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Dawi, Akmal (28 March 2023). "Unseen Taliban Leader Wields Godlike Powers in Afghanistan". Voice of America. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- .

[Akhundzada] has not convened the Taliban's Leadership Council (a 'politburo' of top leaders and commanders) for several months. Instead, he relies on the narrower Kandahar Council of Clerics for legal advice.

- ^ Central Statistics Office Afghanistan

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Afghanistan". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition.)

- ^ a b c d e f "Afghanistan". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ISBN 9789211264517. Archived(PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Archived(PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Taliban Changes Solar Year to Hijri Lunar Calendar". Hasht-e Subh Daily. 26 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Half Hour and 45-Minute Time Zones". timeanddate.com.

- ^ "Securing Stability in Afghanistan, the 'Heart of Asia'". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Ministry of Home Affairs (Department of Border Management)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ د هېواد د وګړو اټکل برآورد نفوس کشور1399 [Estimated Population of Afghanistan 2020–21] (PDF) (Report) (in Arabic and English). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. "Why Is Afghanistan the 'Graveyard of Empires'?". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Griffin, Luke (14 January 2002). "The Pre-Islamic Period". Afghanistan Country Study. Illinois Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 3 November 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ISBN 9781135189792.

- ^ "The remarkable rugs of war, Drill Hall Gallery". The Australian. 30 July 2021. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Professing Faith: Religious traditions in Afghanistan are diverse". 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan: the land that forgot time". The Guardian. 26 October 2001.

- ^ "DŌST MOḤAMMAD KHAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 1995. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Who Will Run the Taliban Government?". crisisgroup.org. 9 September 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "The Taliban: Unrecognized and unrepentant". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Morocco seizes over 840 kg of cannabis – Xinhua | English.news.cn". xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan's Saffron on Media | AfGOV". mail.gov.af. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Taliban Takeover Puts Afghanistan's Cashmere, Silk Industries at Risk". The Business of Fashion. 25 August 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^

- "The name Afghan has evidently been derived from Asvakan, the Assakenoi of Arrian... " (Megasthenes and Arrian, p 180. See also: Alexander's Invasion of India, p 38; J.W. McCrindle).

- "Even the name Afghan is Aryan being derived from Asvakayana, an important clan of the Asvakas or horsemen who must have derived this title from their handling of celebrated breeds of horses" (See: Imprints of Indian Thought and Culture Abroad, p 124, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan).

- cf: "Their name (Afghan) means "cavalier" being derived from the Sanskrit, Asva, or Asvaka, a horse, and shows that their country must have been noted in ancient times, as it is at the present day, for its superior breed of horses. Asvaka was an important tribe settled north to Kabul river, which offered a gallant resistance but ineffectual resistance to the arms of Alexander." (Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1999, p. 275, Royal Scottish Geographical Society)

- "Afghans are Assakani of the Ashvakameaning 'horsemen'." (Sva, 1915, p. 113, Christopher Molesworth Birdwood)

- Cf: "The name represents Sanskrit Asvaka in the sense of a cavalier, and this reappears scarcely modified in the Assakani or Assakeni of the historians of the expedition of Anglo-Indianwords and phrases, and of kindred terms, etymological. Henry Yule, A. D. Burnell).

- ISBN 978-8-12080-436-4.

- ^ Ch. M. Kieffer (15 December 1983). "Afghan". Encyclopædia Iranica (online ed.). Columbia University. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013.

- ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 317.

- ^ a b Afghanistan – John Ford Shroder, University of Nebraska. Encarta. Archived from the original on 17 July 2004. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Afghanistan: A Treasure Trove for Archaeologists". Time. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ISBN 978-0521576529. Archivedfrom the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1998). Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation. pp.96

- ^ Louis Depree (1981). Notes on Shortugai: An Harappan Site in Northern Afghanistan. Centre for the Study of the Civilization of Central Asia.

- ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

- ^ "Chronological History of Afghanistan – the cradle of Gandharan civilisation". Gandhara.com.au. 15 February 1989. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ a b Gnoli, Gherado (1989). The Idea of Iran, an Essay on its Origin. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. p. 133.

... he would have drawn inspiration from a ireligious policy which intended to counteract the Median Magi's influence and transfer the 'Avesta-Schule' from Arachosia to Persia: thus the Avesta would have arrived in Persia through Arachosia in the 6th century B.C. [...] Alltough [...] Arachosia would have been only a second fatherland for Zoroastrianism, a significant role should still be attributed to this south-eastern region in the history of the Zoroastrian tradition.

- ^ a b Gnoli, Gherado (1989). The Idea of Iran, an essay on its Origin. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. p. 133.

linguistic data [...] prove the presence of the Zoroastrian tradition in Arachosia both in the Achaemenian age, in the last quarter of the 6th century, and in the Seleucid age.

- ^ a b "ARACHOSIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Country Profile: Afghanistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Runion 2007, p. 44.

- ^ "'Afghanistan and the Silk Road: The land at the heart of world trade' by Bijan Omrani". UNAMA. 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Afghanistan – Silk Roads Programme". UNESCO.

- ISBN 0-391-04173-8. Archivedfrom the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Afghan and Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1.

- ISBN 978-92-3-103850-1.

Gradually there emerged a fabulous syncretism between the Hellenistic world and the Buddhist universe

- ^ Grenet, Grenet (2016). Zoroastriansm among the Kushans.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-349-14218-0.

With Aurmuzd, Sroshard, Narasa and Mihr, we are on safer ground because all are Zoroastrian deities: Aurmuzd is the supreme god of light, Ahura Mazda; and Mihr, the sun god, is linked with the Iranian Mithra. Exactly the same non-Buddhist[...]

- ISBN 978-0-7391-3609-6.

- ISBN 978-0-297-86559-9.

.. when the patriarch at Ctesiphon had to broker a compromise that left one bishop at the capital Zaranj and another further east at Bust, now in southern Afghanistan. A Christian text composed in about 850 also records a monastery of ...

- ISBN 978-965-278-223-6.

The Jews of Afghanistan According to tradition, the first Jews reached ... in Hebrew script found in the Tang - e Azao Valley in the Ghor region ...

- ISBN 9780801464898.

At the time of the first Muslim advances, numerous local natural religions were competing with Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Hinduism in the territory of modern Afghanistan.

- ISBN 978-0-19-879253-6.

The Rabatak inscription includes Miiro amongst a list of gods: Nana, Ahura Mazda, and Narasa. All of these gods likely had images dedicated at the Bagolaggo, presumably alongside statues of Kanishka

- ISBN 978-0-349-14218-0.

The two most important deities are goddesses: one is the lady Nana', daughter of the moon god and sister of the sun god, the Kushan form of Anahita, Zoroastrian goddess of fertility

- ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Hamd-Allah Mustawfi of Qazwin (1340). "The Geographical Part of the NUZHAT-AL-QULUB". Translated by Guy Le Strange. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Ewans 2002, p. 22–23.

- ^ Richard F. Strand (31 December 2005). "Richard Strand's Nuristân Site: Peoples and Languages of Nuristan". nuristan.info. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Richard Nyrop; Donald Seekins, eds. (1986). Afghanistan: A Country Study. Foreign Area Studies, The American University. p. 10.

- ^ Ewans 2002, p. 23.

- ^ "Central Asian world cities". Faculty.washington.edu. 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Page, Susan (18 February 2009). "Obama's war: Deploying 17,000 raises stakes in Afghanistan". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- S2CID 154120015.

- ^ Periods of World History: A Latin American Perspective – Page 129

- ^ The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia – Page 465

- ^ Barfield 2012, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Barfield 2012, pp. 75.

- ^ Dupree 1997, pp. 319, 321.

- ISBN 9780190914400.

- ^ "Khurasan". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. 2009. p. 55.

In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the term "Khurassan" frequently had a much wider denotation, covering also parts of what are now Soviet Central Asia and Afghanistan

- ISBN 978-0-415-34473-9. Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2017.

- ^ Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (1560). "Chapter 200: Translation of the Introduction to Firishta's History". The History of India. Vol. 6. Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 8. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b Edward G. Browne. "A Literary History of Persia, Volume 4: Modern Times (1500–1924), Chapter IV. An Outline of the History Of Persia During The Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ "Ahmad Shah Durrani". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ Friedrich Engels (1857). "Afghanistan". Andy Blunden. The New American Cyclopaedia, Vol. I. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ISBN 9781849043427.

- ISBN 978-3-7001-7202-4.

- ^ Mehta, p. 248.

- ^ History of Islam, p. 509, at Google Books

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 122-123.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 149.

- ^ Muhammad Katib Hazarah, Fayz (2012). "The History Of Afghanistan Fayż Muḥammad Kātib Hazārah's Sirāj Al Tawārīkh By R. D. Mcchesney, M. M. Khorrami". AAF: 131. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Muhammad Khan, Ashiq (1998). THE LAST PHASE OF MUSLIM RULE IN MULTAN (1752–1818) (Thesis). University of Multan, MULTAN. p. 159. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 155.

- ^ a b Lee 2019, p. 158.

- ^ a b Lee 2019, p. 162.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 166.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 172.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 176.

- ISBN 978-0-306-81826-4.

- ISBN 978-1-78914-010-1.

- ^ Lee 2019, p. 205.

- ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- JSTOR 40105749. Archived from the originalon 16 August 2016.

- ISBN 0714632465. p7-19

- ^ Onley, James (March 2009). "The Raj Reconsidered: British India's Informal Empire and Spheres of Influence in Asia and Africa" (PDF). Routledge. Page 9 of URL/Page 52. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "Afghan Women Hope for More Gains Under New Administration – Afghanistan". ReliefWeb. 22 October 2014.

- ^ "Afghanistan – HISTORY". Country Studies US.

- ISBN 9780817982133.

- S2CID 159788830.

- ISBN 9780275978785.

- S2CID 160565967.

- ^ "Afghanistan". Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 25. Americana Corporation. 1976. p. 24.

- ^ "Queen Soraya of Afghanistan: A woman ahead of her time". Arab News. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ISBN 9781558761544. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ISBN 9781558761544. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ISBN 0-313-33089-1. Archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- ISBN 978-1-349-21948-3.

- ^ Ron Synovitz (18 July 2003). "Afghanistan: History Of 1973 Coup Sheds Light On Relations With Pakistan". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Ewans 2002, p. 186–88.

- ISBN 9781440857478.

- ISBN 978-81-7835-262-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-4434-7.

- ISBN 978-1850438571. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Afghanistan: 20 years of bloodshed". BBC News. 26 April 1998. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Barfield 2012, p. 234.

- ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- S2CID 14344770. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ISBN 9780520208933. Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

The Afghans are among the latest victims of genocide by a superpower. Large numbers of Afghans were killed to suppress resistance to the army of the Soviet Union, which wished to vindicate its client regime and realize its goal in Afghanistan.

- ISBN 978-1-4128-3965-5.

During the intervening fourteen years of Communist rule, an estimated 1.5 to 2 million Afghan civilians were killed by Soviet forces and their proxies- the four Communist regimes in Kabul, and the East Germans, Bulgarians, Czechs, Cubans, Palestinians, Indians and others who assisted them. These were not battle casualties or the unavoidable civilian victims of warfare. Soviet and local Communist forces seldom attacked the scattered guerilla bands of the Afghan Resistance except, in a few strategic locales like the Panjsher valley. Instead they deliberately targeted the civilian population, primarily in the rural areas.

- ^ Reisman, W. Michael; Norchi, Charles H. "Genocide and the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

According to widely reported accounts, substantial programmes of depopulation have been conducted in these Afghan provinces: Ghazni, Nagarhar, Lagham, Qandahar, Zabul, Badakhshan, Lowgar, Paktia, Paktika and Kunar...There is considerable evidence that genocide has been committed against the Afghan people by the combined forces of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan and the Soviet Union.

- ISBN 978-0-295-98050-8.

- ^ "Soldiers of God: Cold War (Part 1/5)". CNN. 1998. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ UNICEF, Land-mines: A deadly inheritance Archived 5 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Landmines in Afghanistan: A Decades Old Danger". Defenseindustrydaily.com. 1 February 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Refugee Admissions Program for Near East and South Asia". Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Recknagel, Charles. "Afghanistan: Land Mines From Afghan-Soviet War Leave Bitter Legacy (Part 2)". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ^ "Afghanistan: History – Columbia Encyclopedia". Infoplease.com. 11 September 2001. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ 'Mujahidin vs. Communists: Revisiting the battles of Jalalabad and Khost Archived 2 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. By Anne Stenersen: a Paper presented at the conference COIN in Afghanistan: From Mughals to the Americans, Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), 12–13 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Barfield 2012, pp. 239, 244.

- ^ "Archived Version" (PDF). prr.hec.gov.pk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Afghanistan". publishing.cdlib.org.

- ISBN 978-1-85043-437-5.

- ^ a b "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch. 7 July 2005. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009.

- ^ GUTMAN, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington D.C.

- ^ "Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978–2001" (PDF). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Afghanistan: The massacre in Mazar-i Sharif. (Chapter II: Background)". Human Rights Watch. November 1998. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ "Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978–2001" (PDF). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005. p. 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Matinuddin, Kamal, The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997, Oxford University Press, (1999), pp. 25–26

- ^ a b "Documents Detail Years of Pakistani Support for Taliban, Extremists". George Washington University. 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ Afghanistan: Chronology of Events January 1995 – February 1997 (PDF) (Report). Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. February 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Coll, Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin, 2005), 14.

- ^ Country profile: Afghanistan (published August 2008) Archived 25 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine(page 3). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-1090-3.

- ^ * James Gerstenzan; Lisa Getter (18 November 2001). "Laura Bush Addresses State of Afghan Women". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "Women's Rights in the Taliban and Post-Taliban Eras". A Woman Among Warlords. PBS. 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-86064-830-4.

- ^ Gargan, Edward A (October 2001). "Taliban massacres outlined for UN". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ "Confidential UN report details mass killings of civilian villagers". Newsday. newsday.org. 2001. Archived from the original on 18 November 2002. Retrieved 12 October 2001.

- The Associated Press. 7 January 1998. Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-295-98111-6.

- ^ "Re-Creating Afghanistan: Returning to Istalif". NPR. 1 August 2002. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013.

- ^ Marcela Grad. Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader (1 March 2009 ed.). Webster University Press. p. 310.

- ^ "Ahmed Shah Massoud". History Commons. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-230-21313-5.

- ^ Rashid, Ahmed (11 September 2001). "Afghanistan resistance leader feared dead in blast". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013.

- ^ "Life under Taliban cuts two ways". CSM. 20 September 2001 Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Brigade 055". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013.

- ^ Rory McCarthy (17 October 2001). "New offer on Bin Laden". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ 'Trump calls out Pakistan, India as he pledges to 'fight to win' in Afghanistan Archived 1 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. CNN, 24 August 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "WPO Poll: Afghan Public Overwhelmingly Rejects al-Qaeda, Taliban". University of Maryland Libraries. 30 January 2006. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

Equally large percentages endorse the US military presence in Afghanistan. Eighty-three percent said they have a favorable view of "the US military forces in our country" (39% very favorable). Just 17% have an unfavorable view.

- ^ "Afghan Futures: A National Public Opinion Survey" (PDF). Afghan Center for Socio-economic and Opinion Research. 29 January 2015. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

Seventy-seven percent support the presence of U.S. forces; 67 percent say the same of NATO/ISAF forces more generally. Despite the country's travails, eight in 10 say it was a good thing for the United States to oust the Taliban in 2001. And much more blame either the Taliban or al Qaeda for the country's violence, 53 percent, than blame the United States, 12 percent. The latter is about half what it was in 2012, coinciding with a sharp reduction in the U.S. deployment.

- ^ Tyler, Patrick (8 October 2001). "A Nation challenged: The attack; U.S. and Britain strike Afghanistan, aiming at bases and terrorist camps; Bush warns 'Taliban will pay a price'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1386. S/RES/1386(2001) 31 May 2001. – (UNSCR 1386)

- ^ "United States Mission to Afghanistan". Nato.usmission.gov. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "Afghanistan's Refugee Crisis". MERIP. 24 September 2001.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Civilians at Risk". Doctors Without Borders – USA.

- ^ Makhmalbaf, Mohsen (1 November 2001). "Limbs of No Body: The World's Indifference to the Afghan Tragedy". Monthly Review.

- ^ "Rebuilding Afghanistan". Return to Hope.

- ^ "Japan aid offer to 'broke' Afghanistan". CNN. 15 January 2002.

- ^ "Rebuilding Afghanistan: The U.S. Role". Stanford University.

- ^ Fossler, Julie. "USAID Afghanistan". Afghanistan.usaid.gov. Archived from the original on 17 October 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "Canada's Engagement in Afghanistan: Backgrounder". Afghanistan.gc.ca. 9 July 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ABC News. 31 July 2008. Archived from the originalon 21 December 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Crilly, Rob; Spillius, Alex (26 July 2010). "Wikileaks: Pakistan accused of helping Taliban in Afghanistan attacks". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-317-07407-6.

- ^ "The foreign troops left in Afghanistan". BBC News. 15 October 2015.

- ^ at 11:38 am, 18 May 2018 (18 May 2018). "How Many Troops Are Currently in Afghanistan?". Forces Network.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Huge security as Afghan presidential election looms". BBC News. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "Afghanistan votes in historic presidential election". BBC News. 5 April 2014. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ Harooni, Mirwais; Shalizi, Hamid (4 April 2014). "Landmark Afghanistan Presidential Election Held Under Shadow of Violence". HuffPost. Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ "Afghanistan's Future: Who's Who in Pivotal Presidential Election". NBC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Afghan president Ashraf Ghani inaugurated after bitter campaign". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "U.S. formally ends the war in Afghanistan". No. online. CBA News. Associated Press. 28 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Sune Engel Rasmussen in Kabul (28 December 2014). "Nato ends combat operations in Afghanistan". The Guardian. Kabul. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "U.S. formally ends the war in Afghanistan". CBS News. 28 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "TSG IntelBrief: Afghanistan 16.0". The Soufan Group. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^

- "Body Count – Casualty Figures after 10 Years of the 'War on Terror' – Iraq Afghanistan Pakistan" Archived 30 April 2015 at the , First international edition (March 2015)

- Gabriela Motroc (7 April 2015). "U.S. War on Terror has reportedly killed 1.3 million people in a decade". Australian National Review. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015.

- "220,000 killed in US war in Afghanistan 80,000 in Pakistan: report". Daily Times. 30 March 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015.

- ^ Borger, Julian (18 May 2022). "US withdrawal triggered catastrophic defeat of Afghan forces, damning watchdog report finds". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "US withdrawal prompted collapse of Afghan army: Report". Al Jazeera. 18 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- VOA News. 14 April 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Nic (24 June 2021). "Afghanistan is disintegrating fast as Biden's troop withdrawal continues". CNN.

- ^ "Afghanistan stunned by scale and speed of security forces' collapse". The Guardian. 13 July 2021.

- ^ "President Ashraf Ghani Flees Afghanistan, Taliban Take Over Kabul: Report". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "The Afghan government's collapse is a humiliation for the US and Joe Biden". New Statesman. 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Operations". The National Resistance Front: Fighting for a Free Afghanistan. National Resistance Front of Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Anti-Taliban forces say they've taken three districts in Afghanistan's north". Reuters. 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "An anti-Taliban front forming in Panjshir? Ex top spy Saleh, son of 'Lion of Panjshir' meet at citadel". The Week. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Afghan Vice President Saleh Declares Himself Caretaker President; Reaches Out To Leaders for Support". News18. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Kazmin, Amy; Findlay, Stephanie; Bokhari, Farhan (6 September 2021). "Taliban says it has captured last Afghan region of resistance". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Huylebroek, Jim; Blue, Victor J. (17 September 2021). "In Panjshir, Few Signs of an Active Resistance, or Any Fight at All". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021.

- ^ "Human and Budgetary Costs to Date of the U.S. War in Afghanistan, 2001–2022 | Figures | Costs of War". The Costs of War. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "UCDP – Uppsala Conflict Data Program". ucdp.uu.se.

- ^ "One year later, Austin acknowledges lasting questions over Afghanistan war's end". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Karzai says while the war has ended, unity has not yet been achieved | Ariana News". ariananews.af. 9 March 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Briefing by Special Representative Deborah Lyons to the Security Council". UNAMA. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Hamid Karzai stays on in Afghanistan — hoping for the best, but unable to leave". NPR. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the originalon 28 December 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "گروه طالبان حکومت جدید خود را با رهبری ملا حسن اخوند اعلام کرد". BBC News فارسی.

- ^ "Taliban announce new government for Afghanistan". BBC News. 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Profile: Who is Afghanistan's new caretaker prime minister?". The Express Tribune. 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Hardliners get key posts in new Taliban government". BBC News. 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Taliban Announces Head of State, Acting Ministers". TOLOnews. 7 September 2021. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Taliban Name Their Deputy Ministers, Doubling Down On An All-Male Team". NPR. 21 September 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Who will speak for Afghanistan at the United Nations?". Al Jazeera. 26 September 2021.

- ^ "China urges World Bank, IMF to help Afghanistan". News24. 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Can the Taliban avert a food crisis without foreign aid?". Deutsche Welle. 11 November 2021.

- ^ "'Countdown to catastrophe': half of Afghans face hunger this winter – UN". The Guardian. 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan Facing Famine: UN, World Bank, US Should Adjust Sanctions, Economic Policies". Human Rights Watch. 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Can the Taliban Tackle Corruption in Afghanistan?". VOA. 31 January 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

Taliban-ruled Afghanistan is ranked 150th, a remarkable status upgrade from its 174th ranking in 2021. In 2011, at the height of U.S. military and developmental engagement in Afghanistan, the country was ranked 180th, next to North Korea and Somalia.

- ^ "Taliban blasted for 'shocking oppression' of women". Arab News. 12 September 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Afghan Refugees, Costs of War, "Afghan Refugees | Costs of War". Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013., 2012

- ^ "In numbers: Life in Afghanistan after America leaves". BBC News. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "'What's wrong?': The silence of Pakistanis on expulsion of Afghan refugees". Al Jazeera. 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Afghans Banned From 16 Provinces In Iran As Forced Exodus Continues". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Taliban: Iran Deports Almost 350,000 Afghans Within 3 Months". VOA News. 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Over 1 mn Afghan children facing severe malnutrition, says WHO chief". Business Standard. 22 December 2023.

- ^ * "U.S. maps". Pubs.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "South Asia: Data, Projects, and Research". Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- "Maps Showing Geology, Oil and Gas Fields and Geological Provinces of South Asia (Includes Afghanistan)". Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- "University of Washington Jackson School of International Studies: The South Asia Center". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- "Syracruse University: The South Asia Center". 26 March 2013. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- "Center for South Asian studies". Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". UNdata. 26 April 2011. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Afghanistan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Tan, Anjelica (18 February 2020). "A new strategy for Central Asia". The Hill.

, as Afghan President Ashraf Ghani has noted, Afghanistan is itself a Central Asian country.

- ISBN 9781107619500.

- ISBN 978-9004181595.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Cultural Crossroad at the Heart of Asia". Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Land area (sq. km)". World Development Indicators. World Bank. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "CIA Factbook – Area: 41". CIA. 26 November 1991. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "International Land Border." India Ministry of Home Affairs. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-59033-421-8.

- ^ ISBN 9781857431339.

- ISBN 9781633559899.

- ^ "Forests of Afghanistan" (PDF). cropwatch.unl.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "History of Environmental Change in the Sistan Basin 1976–2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan Rivers Lakes – Afghanistan's Web Site". afghanistans.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Snow in Afghanistan: Natural Hazards". NASA. 3 February 2006. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Snow may end Afghan drought, but bitter winter looms". Reuters. 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013.

- ^ "Afghanistan's woeful water management delights neighbors". The Christian Science Monitor. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- US Geological Survey. Fact Sheet FS 2007–3027. Archived from the original(PDF) on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ "Earthquake Hazards". USGS Projects in Afghanistan. US Geological Survey. 1 August 2011. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Noroozi, Ebrahim (25 June 2022). "Deadly quake a new blow to Afghans enervated by poverty". CTV News. Associated Press. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Earthquakes in Herat Province, Health Situation Report No. 12, November 2023". reliefweb.int. 2 December 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- PMID 30375988.

- ^ "Afghanistan | History, Map, Flag, Capital, Population, & Languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ISBN 9789610500193.

- ^ ISBN 9781438104805.

- ^ "Afghanistan Plant and Animal Life – Afghanistan's Web Site". afghanistans.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ ISBN 9781438108193.

- PMID 33293507.

- ^ Glatzer, Bernt (2002). "The Pashtun Tribal System" (PDF). New Delhi: Concept Publishers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "NSIA Estimates Afghanistan Population at 32.9M". TOLOnews.

- ^ "Afghanistan Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". 2020 World Population by Country. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "United Nations and Afghanistan". UN News Centre. Archived 31 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Afghan Population Estimates 2020". Worldmeters. 2020. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Afghanistan – Population Reference Bureau". Population Reference Bureau. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ^ Wickramasekara, Piyasiri; Sehgal, Jag; Mehran, Farhad; Noroozi, Ladan; Eisazadeh, Saeid. "Afghan Households in Iran: Profile and Impact" (PDF). United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2018.

- PMID 31618275.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Distribution of Afghan population by ethnic group 2020". 20 August 2021.

- ^ "The roots of Afghanistan's tribal tensions". The Economist. 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Constitution of Afghanistan". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Article Sixteen of the 2004 Constitution of Afghanistan". 2004. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

Pashto and Dari are the official languages of the state. Uzbek, Turkmen, Baluchi, Pashai, Nuristani and Pamiri are – in addition to Pashto and Dari – the third official language in areas where the majority speaks them

- ^ The Encyc. Iranica makes clear in the article on Afghanistan — Ethnography that "The term Farsiwan also has the regional forms Parsiwan and Parsiban. In religion they are Imami Shia. In the literature they are often mistakenly referred to as Tajik." Dupree, Louis (1982) "Afghanistan: (iv.) Ethnography", in Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition 2006.

- ^ Bodetti, Austin (11 July 2019). "What will happen to Afghanistan's national languages?". alaraby.

- ^ ISBN 9781857336801.

- ^ The Asia Foundation. Afghanistan in 2018: A Survey of the Afghan People. Archived 7 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Khan, M. Ilyas (12 September 2015). "Pakistan's confusing move to Urdu". BBC News.

- ^ a b "Religion in Afghanistan". The Swedish Committee for Afghanistan (SCA).

- ^ "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Majumder, Sanjoy (25 September 2003). "Sikhs struggle in Afghanistan". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Lavina Melwani. "Hindus Abandon Afghanistan". Hinduism Today. Archived from the original on 11 January 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Sikhs rebuilding gurdwaras". Religioscope. 25 August 2005.

- ^ Chabba, Seerat (8 September 2021). "Afghanistan: What does Taliban rule mean for Sikhs and Hindus?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ N.C. Aizenman (27 January 2005). "Afghan Jew Becomes Country's One and Only". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ The New Arab Staff (7 September 2021). "Last Jew in Afghanistan en route to US: report". The New Arab. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Ben Zion Gad (1 December 2021). "'Last Jew in Afghanistan' loses title to hidden Jewish family". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Gebauer, Matthias (20 March 2006). "Christians in Afghanistan: A Community of Faith and Fear". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ USSD Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2009). "International Religious Freedom Report 2009". Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karimi, Ali (20 March 2015). "Can Cities Save Afghanistan?".

- ^ a b "Unravelling the Afghan art of carpet weaving". aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera.

- Central Statistics Organization. 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Girls excluded as Afghan secondary schools reopen". BBC News. 18 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the originalon 28 December 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- USAID. Archivedfrom the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ Adina, Mohammad Sabir (18 May 2013). "Wardak seeks $3b in aid for school buildings". Pajhwok Afghan News. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "UNESCO UIS: Afghanistan". UNESCO. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ "Taliban reverses decision, barring Afghan girls from attending school beyond 6th grade". NPR. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Six provinces keep schools open for girls despite nationwide ban". AmuTV. 1 January 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Neda Safi, Tooba (17 February 2023). "Girls return to high school in some regions of Afghanistan". Geneva Solutions. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "UN is seeking to verify that Afghanistan's Taliban are letting girls study at religious schools". The Seattle Times. 20 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Afghanistan" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan". UNESCO. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017.

- ^ Peter, Tom A. (17 December 2011). "Childbirth and maternal health improve in Afghanistan". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Afghanistan National Hospital Survey" (PDF). Afghan Ministry of Health. August 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ Gul, Ayaz (20 April 2019). "Pakistan-funded Afghan Hospital Begins Operations". VOA News. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

It opens a new chapter in the friendship of the two countries... This is the second-largest hospital [in Afghanistan] built with your support that will serve the needy," Feroz told the gathering.

- ^ "Health". United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ DiNardo, Anne-Marie; LPA/PIPOS (31 March 2006). "Empowering Afghanistan's Disabled Population – 31 March 2006". Usaid.gov. Archived from the original on 8 May 2004. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (13 February 2008). "Afghanistan's refugee crisis 'ignored'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Afghanistan: People living with disabilities call for integration". The New Humanitarian. 2 December 2004. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Haussegger, Virginia (2 July 2009). "Mahboba's Promise". ABC News (Australia). Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Hardliners get key posts in new Taliban government". BBC News. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Taliban increasingly violent against protesters – UN". BBC News. 24 August 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ V-Dem Institute (2023). "The V-Dem Dataset". Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ "Q&A: What is a loya jirga?". BBC News. 1 July 2002. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Barfield 2012, p. 295.

- ^ "Politicians Express Mixed Reactions to Loya Jirga". TOLO News. 7 August 2020. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Loya Jirga Approves Release of 400 Taliban Prisoners". TOLO News. 9 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Afghanistan's Hekmatyar says heading for Doha with Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah to meet Taliban – Al Jazeera". Reuters. 16 August 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ AFP (18 August 2021). "Taliban met ex-Afghan leader Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah". Brecorder. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Macias, Natasha Turak, Amanda (18 August 2021). "Ousted Afghan President Ashraf Ghani resurfaces in UAE after fleeing Kabul, Emirati government says". CNBC. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ghani says he backs talks as Taliban meet with Karzai, Abdullah". New Age. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Osman, Borhan (July 2016). Taliban Views on a Future State (PDF). New York University. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Taliban expected to announce new government". The Guardian. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Taliban to Follow Iran Model in Afghanistan; Reclusive Hibatullah Akhundzada to be Supreme Leader". News18. 31 August 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Taliban again postpone Afghan govt formation announcement". The Economic Times. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "New 'inclusive' Afghanistan government to be announced soon: Taliban". mint. 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Women protest against all-male Taliban government". BBC News. 8 September 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan Provinces". Ariana News. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ "Explaining Elections, Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan". Iec.org.af. 9 October 2004. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Jamie Boex; Grace Buencamino; Deborah Kimble. "An Assessment of Afghanistan's Municipal Governance Framework" (PDF). Urban Institute Center on International Development and Governance. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Dupree 1997, p. 642.

- ^ "Treaty of Friendship". mea.gov.in. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ "China Embraces High-Stakes Taliban Relationship as U.S. Exits". Bloomberg News. 16 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ Latifi, Ali M (7 October 2021). "Taliban still struggling for international recognition". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Hillary Clinton says Afghanistan 'major non-Nato ally'". BBC News. 7 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Mizelle, Shawna; Fossum, Sam (7 July 2022). "Biden will rescind Afghanistan's designation as a major non-NATO ally". CNN.

- ^ "White House defends letting billions in military equipment fall into Taliban hands". 12 October 2021. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Andrzejewski, Adam. "Staggering Costs – U.S. Military Equipment Left Behind In Afghanistan". Forbes. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Ahmadzai, Aria (7 October 2016). "The LGBT community living under threat of death". BBC News.

- ^ "Afghanistan | Human Dignity Trust". humandignitytrust.org.

- ^ Bezhan, Frud. "'Fake Life': Being Gay in Afghanistan". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ^ "LGBT relationships are illegal in 74 countries, research finds". The Independent. 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Lyons, Kate; Blight, Garry (27 July 2015). "Where in the world is the worst place to be a Christian?". The Guardian.

- AP Archive, 23 March 2006

- ^ George, Susannah (7 May 2022). "Taliban orders head-to-toe coverings for Afghan women in public". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma (7 May 2022). "Taliban order all Afghan women to cover their faces in public". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Shelley, Jo; Popalzai, Ehsan; Mengli, Ahmet; Picheta, Rob (19 May 2022). "Top Taliban leader makes more promises on women's rights but quips 'naughty women' should stay home". Kabul, Afghanistan: CNN. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Zucchino, David; Akbary, Yaqoob (21 May 2022). "The Taliban Pressure Women in Afghanistan to Cover Up". The New York Times. Kabul, Afghanistan. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Gannon, Kathy (8 May 2022). "Taliban divisions deepen as Afghan women defy veil edict". Associated Press. Kabul, Afghanistan. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Fraser, Simon (19 May 2022). "Afghanistan's female TV presenters must cover their faces, say Taliban". BBC News. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Nader, Zahra (28 August 2023). "'Despair is settling in': female suicides on rise in Taliban's Afghanistan". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Thoms, Silja (8 July 2023). "How the Taliban are violating women's rights in Afghanistan". DW. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Ali, Rabia (1 August 2023). "Activists sound alarm over surge in suicides among Afghan women". Anadolu Ajansı. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Taliban dissolves Afghanistan's human rights commission as 'unnecessary'". The Guardian. Reuters. 16 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Mehrotra, Kartikay (16 December 2013). "Karzai Woos India Inc. as Delay on U.S. Pact Deters Billions". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ "Field Listing :: GDP – composition, by sector of origin – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Interest Rate Cut in Place, Says Central Bank". TOLOnews. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "Afghani Falls Against Dollar By 3% In A Month". TOLOnews. 18 April 2019. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (7 July 2010). "Afghan Companies Say U.S. Did Not Pay Them". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ "DCDA | Welcome to our Official Website". dcda.gov.af. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "::Welcome to Ghazi Amanullah Khan Website::". najeebzarab.af. 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Ephgrave, Oliver (2011). "Case study: Aino Mina". Designmena. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "A Humane Afghan City?" by Ann Marlowe. Forbes. 2 September 2009. Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Michael Sprague. "Afghanistan country profile" (PDF). USAID. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ "Economic growth". USAID Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Nickel, Rod (12 April 2018). "Sales of Afghanistan's renowned carpets unravel as war intensifies". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Afghanistan trade balance, exports and imports by country 2019". World Integrated Trade Solution. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "Taliban blames U.S. as 1 million Afghan kids face death by starvation". CBS News. 20 October 2021. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023.

- ^ Fisher, Max; Taub, Amanda (29 October 2021). "Is the United States Driving Afghanistan Toward Famine?". The Interpreter. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Afghanistan's hunger crisis is a problem the U.S. can fix". MSNBC. 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Two Years into Taliban Rule, New Shocks Weaken Afghan Economy". United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Taliban Controls the World's Best Performing Currency This Quarter". Bloomberg.com. 25 September 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "Agriculture". USAID. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ "Unlocking the Potential of Agriculture for Afghanistan's Growth". World Bank.

- ^ Burch, Jonathon (31 March 2010). "Afghanistan now world's top cannabis source: U.N." Reuters.

- ^ "Afghanistan's red gold 'saffron' termed world's best". Arab News. 22 December 2019.

- ^ "Afghan Saffron, World's Best". TOLOnews.

- ^ "Saffron production hits record high in Afghanistan". Xinhua. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019.

- ^ Bryan Denton; David Zucchino; Yaqoob Akbary (29 May 2022). "Green Energy Complicates the Taliban's New Battle Against Opium: The multibillion-dollar trade has survived previous bans. Now, the Taliban are going after solar-powered water pumps to try to dry up poppy crops in the middle of a national economic crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

Do not destroy the fields, but make the fields dry out.... We are committed to fulfilling the opium decree.

- ^ David Mansfield (23 May 2022). "When the Water Runs Dry: What is to be done with the 1.5 million settlers in the deserts of southwest Afghanistan when their livelihoods fail?". areu.org.af. The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Poppy Cultivation in South of Afghanistan Down by 80%: Report". ToloNews. 7 June 2023. p. 1. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Afghan opium poppy cultivation plunges by 95 percent under Taliban: UN". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Opium cultivation declines by 95 per cent in Afghanistan: UN survey | UN News". news.un.org. 5 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ US Geological Survey/Afghanistan Geological Survey. Fact Sheet 2007–3063. Archived from the original(PDF) on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Minerals in Afghanistan" (PDF). British Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Afghans say US team found huge potential mineral wealth". BBC News. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Michael E. "Deposits Could Aid Ailing Afghanistan" (Archived 23 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine), []The Brookings Institution]], 16 June 2010.

- ^ Klett, T.R. (March 2006). Assessment of Undiscovered Petroleum Resources of Northern Afghanistan, 2006 (PDF) (Technical report). USGS-Afghanistan Ministry of Mines & Industry Joint Oil & Gas Resource Assessment Team. Fact Sheet 2006–3031. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Afghanistan signs '$7 bn' oil deal with China". 28 December 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ "Afghanistan's Mineral Fortune". Institute for Environmental Diplomacy and Security Report. 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Tucker, Ronald D. (2011). Rare Earth Element Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and Preliminary Resource Assessment of the Khanneshin Carbonatite Complex, Helmand Province, Afghanistan (PDF) (Technical report). USGS. Open-File Report 2011–1207. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "China, Not U.S., Likely to Benefit from Afghanistan's Mineral Riches". Daily Finance. 14 June 2010 Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "China Willing to Spend Big on Afghan Commerce". The New York Times. 29 December 2009. Archived from the original on 31 July 2011.