Song sparrow

| Song sparrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| in Brooklyn, New York , USA

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passerellidae |

| Genus: | Melospiza |

| Species: | M. melodia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Melospiza melodia (Wilson, 1810)

| |

| |

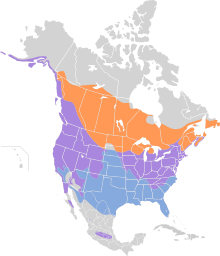

| Part of the range of M. melodia Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Melospiza cinerea | |

The song sparrow (Melospiza melodia) is a medium-sized New World sparrow. Among the native sparrows in North America, it is easily one of the most abundant, variable and adaptable species.

Description

Adult song sparrows have brown upperparts with dark streaks on the back and are white underneath with dark streaking and a dark brown spot in the middle of the breast. They have a brown cap and a long brown rounded tail. Their face is gray with a brown streak through each eye. They are highly variable in size across numerous subspecies (for subspecies details, see below). The body length ranges from 11 to 18 cm (4.3 to 7.1 in) and wingspan can range from 18 to 25.4 cm (7.1 to 10.0 in).[2][3] Body mass ranges from 11.9 to 53 g (0.42 to 1.87 oz).[4] The average of all races is 32 g (1.1 oz) but the widespread nominate subspecies (M. m. melodia) weighs only about 22 g (0.78 oz) on average. The maximum lifespan in the wild is 11.3 years.[5] The eggs of the song sparrow are brown with greenish-white spots. Females lay three to five eggs per clutch, with an average incubation time of 13–15 days before hatching.

In the field, they are most easily confused with the Lincoln's sparrow and the Savannah sparrow. The former can be recognized by its shorter, grayer tail and the differently-patterned head, the brown cheeks forming a clear-cut angular patch. The Savannah sparrow has a forked tail and yellowish flecks on the face when seen up close.

Distribution and life history

Though a habitat generalist, the song sparrow favors brushland and marshes, including salt marshes across most of Canada and the United States. They also thrive in human dominated areas such as in suburbs, agricultural fields, and along roadsides. Permanent residents of the southern half of their range, northern populations of the song sparrow migrate to the southern United States or Mexico during winter and intermingle with the native, non-migratory population. The song sparrow is a very rare vagrant to western Europe, with a few recorded in Great Britain and Norway.

These birds forage on the ground, in shrubs or in very shallow water. They eat mainly insects and seeds. Birds in salt marshes may also eat small

Physiology

The song sparrow has been the subject of several studies detailing the physiological reactions of bird species to conditions such as daylight length and differing climatic conditions. Most birds gain mass in their reproductive organs in response to some signal, either internal or external as the breeding season approaches. The exact source of this signal varies from species to species – for some, it is an endogenous process separate from environmental cues, while other species require extensive external signals of changing daylight length and temperature before beginning to increase the mass of their reproductive organs. Male specimens of M. melodia gain significant testicular mass in response both to changes in the daily photoperiod and as a result of endogenous chemical signals.[7] Females also undergo significant ovarian growth in response to both photo-period and endogenous signals. Hormone levels in both males and females fluctuate throughout the breeding season, having very high levels in March and late April and then declining until May.[8] These studies suggest that there are multiple factors at work that influence when and how the song sparrow breeds other than just increasing day length.

Due to the myriad subspecies of the song sparrow and the extremely varied climate of southern California, where many of these subspecies make their homes, physiological studies were undertaken to determine how climatic conditions and local environment influenced the bill size of M. melodia subspecies. The bill of a bird is highly important for thermoregulation as the bare surface area makes a perfect place to radiate excess heat or absorb solar energy to maintain homeostasis.[9] Knowing this, comparisons of bill length between individual song sparrows collected in different habitats were made with regard to the primary habitat type or microclimate that they were collected in. Larger beaked subspecies were strongly correlated with hotter microclimates - a correlation that follows from the conditions of Allen's Rule.[10]

Song

The sparrow species derives its name from its colorful repertoire of songs. Enthusiasts report that one of the songs heard often in suburban locations closely resembles the opening four notes of Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. The male uses a fairly complex song to declare ownership of its territory and attract females.

Singing itself consists of a combination of repeated notes, quickly passing isolated notes, and trills. The songs are very crisp, clear, and precise, making them easily distinguishable by human ears. A particular song is determined by not only pitch and rhythm but also the timbre of the trills. Although one bird will know many songs—as many as 20 different tunes with as many as 1000 improvised variations on the basic theme,[11]—unlike thrushes, the song sparrow usually repeats the same song many times before switching to a different song.

Song sparrows typically learn their songs from a handful of other birds that have neighboring territories. They are most likely to learn songs that are shared between these neighbors. Ultimately, they will choose a territory close to or replacing the birds that they have learned from. This allows the song sparrows to address their neighbors with songs shared with those neighbors. It has been demonstrated that song sparrows are able to distinguish neighbors from strangers on the basis of song, and also that females are able to distinguish (and prefer) their mate's songs from those of other neighboring birds, and they prefer songs of neighboring birds to those of strangers.[12]

A 2022 study by Duke University also found that male song sparrows memorize a 30-minute long playlist of their songs and use that information to curate both their current playlist and the following one. The findings suggest that male song sparrows deliberately shuffle and repeat their songs possibly to keep a female's attention.[13]

Predators and parasites

Common predators of the song sparrow include cats, hawks, and owls; however snakes, dogs, and the American kestrel are treated ambiguously, suggesting that they are less of a threat[citation needed]. The song sparrow recognizes enemies by both instinctual and learned patterns (including cultural learning), and adjusts its future behavior based on both its own experiences in encounters, and from watching other birds interact with the enemies. Comparisons of experiments on hand-raised birds to observation of birds in the wild suggest that the fear of owls and hawks is instinctual, but fear of cats is learned.[14]

Song sparrows' nests are parasitized by the brown-headed cowbird. The cowbirds' eggs closely resemble song sparrows' eggs, although the cowbirds' eggs are slightly larger. Song sparrows recognize cowbirds as a threat and attack the cowbirds when they are near the nest. There is some evidence that this behavior is learned rather than instinctual.[14] A more recent study found that the behavior of attacking female cowbirds near nests may actually attract cowbird parasitism because the female cowbirds use such behavior to identify female song sparrows that are more likely to successfully raise a cowbird chick.[15] One study found that while cowbird parasitism did result in more nest failure, overall there were negligible effects on song sparrow populations when cowbirds were introduced to an island. The study pointed to a number of explanatory factors including song sparrows raising multiple broods, and song sparrows' abilities to raise cowbird chicks with their own.[16]

Subspecies

The song sparrow is one of the most

Eastern group

Small, brownish, long-winged forms with strong black streaks.

- Melospiza melodia melodia (Wilson, 1810). The New York State. In winter, they migrate southeastwards. Very contrasting, very light with black streaks below, and gray margins to back feathers. This population includes the forms named as M. m. juddi Bishop, 1896; M. m. acadica Thayer and Bangs, 1914; M. m. beata (non Bangs) Todd, 1930; M. m. euphonia Wetmore, 1936; M. m. callima Oberholser, 1974; and M. m. melanchra Oberholser, 1974.

- Melospiza melodia atlantica Todd, 1924. Inhabits the Atlantic Coast sand dunes and salt marshes from New York State southwards. Differs from nominate by a gray back. Includes M. m. rossignolii Bailey, 1936.

- Melospiza melodia montana Henshaw, 1884. The subspecies west of melodia to the Rocky Mountains. Some birds from the northern part of its range migrate to north-west Mexico in winter. Similar to nominate, but larger, duller coloration and more slender bill. Includes M. m. fisherella Oberholser, 1911.

Northwestern group

Large, dark, diffuse dark streaks. A study of

- Melospiza melodia maxima Gabrielson & Lincoln, 1951, giant song sparrow. W Aleutian Islands (Attu to Atka Island), resident. The largest subspecies, about the size of the California towhee. Very gray overall, long, diffuse streaks. Bill long and slender.

- Melospiza melodia sanaka McGregor, 1901, Aleutian song sparrow. Aleutians from Alaskan Peninsula; resident. Similar to maxima; grayer still and bill even more slender. Includes the Semidi song sparrow, M. m. semidiensis Brooks, 1919, which may be a distinct subspecies however.[20] Also includes the population from Amak Island[21]named M. m. amaka Gabrielson & Lincoln, 1951 (Amak song sparrow) which was extirpated due to habitat destruction, apparently disappearing in the weeks around New Year's Eve, 1980/1981 (there were unconfirmed sightings in 1987 and 1988).

- Melospiza melodia insignis Baird, 1869, Bischoff song sparrow. on Alaska Peninsula; many migrate south in winter. A darkish gray, medium-sized form.

- Melospiza melodia kenaiensis Ridgway, 1900, Kenai song sparrow. Resident; Pacific coast of Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound islands; some resident, some migrant. Smaller and browner than insignis.

- Melospiza melodia caurina Ridgway, 1899, Yakutat song sparrow. Northern Gulf of Alaska coast, many migrate to Pacific Northwest in winter. A smaller version of kenaiensis.

- Melospiza melodia rufina (Bonaparte, 1850), sooty song sparrow. Outer islands of Alexander Archipelago and Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands); most are resident. A very dark, rufous, and small form. Includes M. m. kwaisa Cumming, 1933.

- Melospiza melodia morphna Oberholser, 1899. Coastal region of central British Columbia south to NW Oregon; resident. Lighter, more rufous than rufina. Previously M. m. cinerea (non Gmelin) (Audubon, 1839); M. m. phaea Fisher, 1902 are Central Oregon hybrids between this subspecies and M. m. cleonensis.

- Melospiza melodia merrilli Brewster, 1896. Occurs between the ranges of morphna and montana south to N Nevada; some migrate south in winter. Includes M. m. ingersolli McGregor, 1899 and M. m. inexspectata Riley, 1911 (Riley song sparrow; inexpectata is a common lapsus). Doubtfully distinct; intermediate between morphna and montana in appearance also and may be hybrid birds.

- Melospiza melodia cleonensis McGregor, 1899. SW Oregon west of Cascade Mountains south to NW California. Brownish-buffish, notably on the flanks; no gray on back; underside with somewhat diffuse chestnut streaks.

Cismontane California group

Small, well-marked and short-winged brownish forms. All resident, except occasional birds from upland populations.

- Melospiza melodia gouldii Baird, 1858. Coastal central California, except San Francisco Bay. A very brown and clear-marked subspecies; buffish (not light gray) fringes of upper back. M. m. santaecrucis Grinnell, 1901 are hybrids with birds from southwards and Central Valley populations.

- Melospiza melodia samuelis (Baird, 1858), San Pablo song sparrow. N San Francisco Bay and San Pablo Bay saltmarshes. A small, tiny-billed subspecies with dirty olive upperpart background.

- Melospiza melodia maxillaris Grinnell, 1909, Suisun song sparrow. Suisun Bay marshes. Dark upperparts; brown with gray mantle edges; plump bill base.

- Melospiza melodia pusillula Ridgway, 1899, Alameda song sparrow. E San Francisco Bay saltmarshes. Yellowest subspecies, paler than samuelis and clear yellow hue below.

- Melospiza melodia heermanni Baird, 1858. Central coastal California and Central Valley south to N Baja California. Similar in color to maxillaris but medium-sized mainland subspecies. Some N-S variation with birds becoming blacker on backs, local populations once separated as M. m. cooperi Ridgway, 1899 and M. m. mailliardi Grinnell, 1911. The latter, occurring around Modesto, may be distinct.

- Melospiza melodia graminea Townsend, 1890. Described from Santa Rosa and Anacapa Islands as M. m. clementae Townsend, 1890. Hybrid population with heermanni on Santa Cruz Island. Extirpated on Santa Barbara (and possibly San Clemente) by feral cats, c. 1967–1970.

Southwestern group

Small, pale, streaks rufous; all resident.

- Melospiza melodia fallax (Baird, 1854), desert song sparrow. Sonoran and parts of Mojave Deserts to E Arizona. A pale ruddy desert form. Synonyms are M. m. saltonis Grinnell, 1909, M. m. virginis Marshall and Behle, 1942 and M. m. bendirei Phillips, 1943.

- Melospiza melodia rivularis Bryant, 1888. Central Baja California. Similar to fallax, lightly streaked breast and long slender bill.

- Melospiza melodia goldmani Nelson, 1899. Not yet found outside El Salto area, Sierra Madre Oriental. Dark reddish brown back with brownish streaks just as in morphna.

Mexican Plateau group

Almoloya del Rio, Mexico

Black-spotted, white throats; all resident.

- Melospiza melodia adusta Nelson, 1899. Zacapú to Lake Yuriria. Bold black pattern on belly and back, clear white throat. Birds become less ruddy brown going east.

- Melospiza melodia villai Phillips and Dickerman, 1957. Headwaters of Río Lerma near Toluca. Darker and duller brown than adusta, distinctly large.

- Melospiza melodia mexicana Ridgway, 1874. Hidalgo to Puebla. Duller and paler than adusta, birds becoming grayish going south. Includes M. m. azteca Dickerman, 1963 and M. m. niceae Dickerman, 1963. "M. m. pectoralis" (ex von Müller, 1865) cannot be assigned to a known song sparrow population.

- Melospiza melodia zacapu Dickerman, 1963.

Conservation status

Seen as a whole, the song sparrow is widespread and common enough to be classified as Species of Least Concern by the

References

- . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "eNature: Song Sparrow Melospiza melodia". Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ^ The Cornell lab of ornithology: Song Sparrow Melospiza melodia

- ISBN 978-0849342585.

- .

- .

- PMID 8138105.

- PMID 6510698.

- ISBN 9781405107242.

- PMID 23206140.

- JSTOR 4074494.

- S2CID 8210185.

- PMID 35078357.

- ^ JSTOR 4079104.

- S2CID 22507458.

- JSTOR 1369102.

- S2CID 154943.

- PMID 32075855.

- JSTOR 4088273.

- JSTOR 1364957.

- doi:10.2326/osj.3.133.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) (2006). California Bird Species of Special Concern.

Further reading

- Beecher, M.D.; Campbell, S.E.; Stoddard, P.K. (1994). "Correlation of Song Learning and Territory Establishment Strategies in the Song Sparrow" (PDF). PMID 11607460.

- Stoddard, Beecher; Horning, C.L.; Campbell, S.E. (1991). "Recognition of individual neighbors by song in the song sparrow, a species with song repertoires". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 29 (3): 211–215. S2CID 44213466.

- O'Loghlen, A.L.; Beecher (1997). "Sexual preferences for mate song types in female song sparrows" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 53 (4): 835–841. S2CID 12750867.

- Smith, J.N.M.; et al. (1997). "A metapopulation approach to the population biology of the Song Sparrow Melospiza melodia". Ibis. 138 (4): 120–128. .

External links

- Song sparrow ID, including sound and video, at Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Song sparrow facts at BirdHouses101.com

- Song sparrow at Xeno-canto

- Song sparrow - Melospiza melodia - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- "Song sparrow media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Song sparrow photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)