Cultural depictions of tigers

Tigers have had symbolic significance in many different cultures. They are considered one of the charismatic megafauna, and are used as the face of conservation campaigns worldwide. In a 2004 online poll conducted by cable television channel Animal Planet, involving more than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries, the tiger was voted the world's favourite animal with 21% of the vote, narrowly beating the dog.[1]

Mythology, religion and folklore

In

The tiger's tail appears in stories from countries including China and Korea, it being generally inadvisable to grasp a tiger by the tail.

In

In Bhutan, the tiger is venerated as one of the four powerful animals called the "four dignities", and a tigress is believed to have carried Padmasambhava from Singye Dzong to the Paro Taktsang monastery in the late 8th century.[10] In the Greco-Roman world, the tiger was depicted being ridden by the god Dionysus.[11] The Warli of western India worship the tiger-like god Waghoba. The Warli believe that shrines and sacrifices to the deity will lead to better coexistence with the local big cats, both tigers and leopards, and that Waghoba will protect them when they enter the forests.[12]

The weretiger replaces the werewolf in shapeshifting folklore in Asia;[13] in India they were evil sorcerers, while in Indonesia and Malaysia they were somewhat more benign.[14] In Taiwanese folk beliefs, Aunt Tiger portrays the story of a tiger, which turns into an old woman, abducts children at night and devours them to satisfy her appetite.[15]

Art

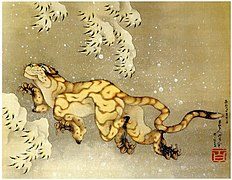

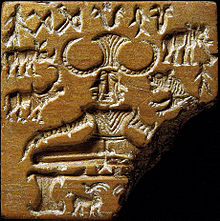

Representations of tigers have been discovered dating at least as far back as 5000 BC, during the

The

In Korea, the painting "Jakhodo" (in leopard paintings, "Jakpyodo"; "pyo" means leopard) is about a magpie and a tiger. The letter "jak" means magpie; "ho" means tiger; and "do" means painting. Since the work is known to keep away evil influence, there is a tradition to hang the art piece in the house in the first month of the lunar calendar. On a branch of a green pine tree sits a magpie and the tiger (or leopard), with a humorous expression, looks up at the bird. The tiger in "Jakhodo" does not look anything like a strong creature with power and authority.

Kkachi horangi, paintings depicting magpies and tigers, was a prominent motif in the minhwa folk art of the Joseon period. Kkachi pyobeom paintings depict magpies and leopards. In kkachi horangi paintings, the tiger, which is intentionally given a ridiculous and stupid appearance (hence its nickname "idiot tiger" 바보호랑이), represents authority and the aristocratic yangban, while the dignified magpie represents the common people. Hence, kkachi horangi paintings of magpies and tigers were a satire of the hierarchical structure of Joseon's feudal society.[16][17]

Tigers have also been featured in Western paintings.

-

Tiger, 1912 by Franz Marc

Literature and media

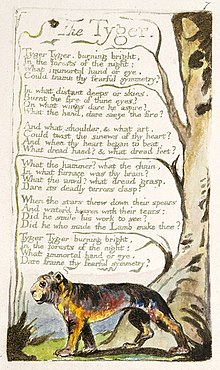

In the Hindu epic Mahabharata, the tiger is fiercer and more ruthless than the lion.[19] William Blake's poem "The Tyger" portrays the tiger as a menacing and fearful animal, and the tiger Shere Khan in Rudyard Kipling's 1894 The Jungle Book is the mortal enemy of the human protagonist.[20] Yann Martel's novel Life of Pi features the title character surviving shipwreck for months on a small boat with a large Bengal tiger while avoiding being eaten. The story was adapted in Ang Lee's feature film of the same name in 2012.[21]

Friendly tiger characters include

Music

The wooden

Heraldry and emblems

The tiger is one of the animals displayed on the

A yellow tiger was used as the primary emblem of the flag of the short-lived

In European heraldry, the

References

- ^ "Endangered tiger earns its stripes as the world's most popular beast". The Independent. December 6, 2004. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85538-118-6.

- ^ "Tiger's Tail". Cultural China. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ISBN 9780313069345.

- ^ Bella Kim (2021-09-28). "'CHANGGWI' Review: What Ghosts Think of Us". The Harvard Crimson.

- ISBN 9781435296152.

- ^ Sivkishen (2014). Kingdom of Shiva. New Delhi: Diamond Pocket Books Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ Balambal, V. (1997). 19. Religion – Identity – Human Values – Indian Context. Bioethics in India: Proceedings of the International Bioethics Workshop in Madras: Biomanagement of Biogeoresources, 16–19 January 1997. Eubios Ethics Institute. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ISBN 978-8184751826. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-521-00230-1.

- hdl:11250/2990288.

- ISBN 978-0-517-18093-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-7218-5.

- S2CID 144937417.

- ^ "까치호랑이". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ KOREA Magazine March 2017. Korean Culture and Information Service. 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ISBN 1-59315-024-5.

- ^ Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa. "SECTION LXVIII". The Mahabharata. Translated by Ganguli, K. M. Retrieved 15 June 2016 – via Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ISBN 978-1861892768.

- ISBN 978-0062114136.

- ISBN 978-0300056457.

- ISBN 978-1403476517.

- ^ Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja (2009) Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 84.

- ISBN 9788131711200.

- ISBN 9789353881054.

- ^ "National Animal". Government of India Official website. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-8225-2674-2.

- Fox-Davies, A. (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: T. C. and E. C. Jack. pp. 191–192.