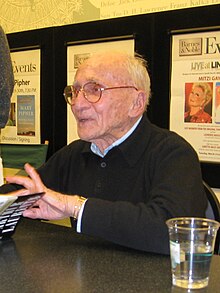

Arthur Laurents

Arthur Laurents | |

|---|---|

| Partner | Tom Hatcher (co. 1954; d. 2006) |

Arthur Laurents (July 14, 1917 – May 5, 2011) was an American playwright, theatre director, film producer and screenwriter.

After writing scripts for radio shows after college and then

Laurents also worked as a screenwriter on

Early life

Born Arthur Levine, Laurents was the son of middle-class Jewish parents, his father a lawyer and his mother a schoolteacher, who gave up her career when she married.

His paternal grandparents were

After graduating from

Career

Theatre

According to John Clum, "Laurents was always a mirror of his times. Through his best work, one sees a staged history of leftist, gender, and gay politics in the decades after World War II."[12] After graduating from Cornell University in 1937, Laurents, who was gay, went to work as a writer for radio drama at CBS in New York. His military duties during World War II, which consisted of writing training films and radio scripts for Armed Service Force Presents, brought him into contact with some of the best film directors—distinguished director George Cukor directed his first script. Laurents's work in radio and film during World War II was an excellent apprenticeship for a budding playwright and screenwriter. He also had the good fortune to be based in New York City. His first stage play, Home of the Brave, was produced in 1945. The sale of the play to a film studio gave Laurents the entrée he needed to become a Hollywood screenwriter though he continued, with mixed success, to write plays. The most important of his early screenplays is his adaptation of Rope for Alfred Hitchcock.[13]

Soon after being discharged from the Army, Laurents met ballerina Nora Kaye, and the two became involved in an on-again, off-again romantic relationship. While Kaye was on tour with Fancy Free, Laurents continued to write for the radio but was becoming discontented with the medium. In 1962, Laurents directed I Can Get It for You Wholesale, which helped to turn then-unknown Barbra Streisand into a star. His next project was the stage musical Anyone Can Whistle, which he directed and for which he wrote the book, but it proved to be an infamous flop. He later had success with the musicals Hallelujah, Baby! (written for Lena Horne[14] but ultimately starring Leslie Uggams) and La Cage Aux Folles (1983), which he directed, however Nick & Nora was not successful.

In 2008, Laurents directed a Broadway revival of Gypsy starring

Hollywood

Laurents' first Hollywood experience proved to be a frustrating disappointment. Director Anatole Litvak, unhappy with the script submitted by Frank Partos and Millen Brand for The Snake Pit (1948), hired Laurents to rewrite it. Partos and Brand later insisted the bulk of the shooting script was theirs, and produced carbon copies of many of the pages Laurents actually had written to bolster their claim. Having destroyed the original script and all his notes and rewritten pages after completing the project, Laurents had no way to prove most of the work was his, and the Writers Guild of America denied him screen credit. Brand later confessed he and Partos had copied scenes written by Laurents and apologized for his role in the deception. Four decades later, Laurents learned he was ineligible for WGA health benefits because he had failed to accumulate enough credits to qualify. He was short by one, the one he failed to get for The Snake Pit.[18]

Upon hearing

Laurents also scripted

Blacklist

Because of a casual remark made by Russel Crouse, Laurents was called to Washington, D.C., to account for his political views.[22] He explained himself to the House Un-American Activities Committee, and his appearance had no obvious impact on his career, which at the time was primarily in the theatre. When the McCarran Internal Security Act, which prohibited individuals suspected of engaging in subversive activities from obtaining a passport, was passed in 1950, Laurents and Granger immediately applied for and received passports and departed for Paris with Harold Clurman and his wife Stella Adler. Laurents and Granger remained abroad, traveling throughout Europe and northern Africa, for about 18 months.[23]

Years earlier, Laurents and

about directing a screen version, the studio agreed as long as Laurents was not part of the package.It was only then that Laurents learned he officially had been

Memoirs

Laurents wrote Original Story By Arthur Laurents: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood, published in 2000. In it, he discusses his lengthy career and his many gay affairs and long-term relationships, including those with

Laurents wrote Mainly on Directing: Gypsy, West Side Story and Other Musicals, published in 2009, in which he discussed musicals he directed and the work of other directors he admired.

His last memoir titled The Rest of the Story was published posthumously in September 2012.

Death

Laurents died from complications of pneumonia at his home in Manhattan on May 5, 2011, aged 93.[28] Following a long tradition, Broadway theatre lights were dimmed at 8 p.m. on May 6, 2011, for one minute in his memory.[29] His ashes were buried alongside those of Tom Hatcher in a memorial bench in Quogue, Long Island, New York.[1]

Work

Writing

- Musicals

- Tony Nomination for Best Musical

- Tony Nomination for Best Musical

- Anyone Can Whistle – 1964

- Do I Hear a Waltz? – 1965

- Hallelujah, Baby! – 1967 – Tony Award for Best Musical

- The Madwoman of Central Park West – 1979

- Nick & Nora – 1991

- Novels

- Harper & Row(New York City)

- OCLC 11014907

- Plays

- Home of the Brave – 1945

- The Bird Cage – 1950

- The Time of the Cuckoo – 1952

- A Clearing in the Woods – 1957

- Invitation to a March – 1960

Directing

- Invitation to a March – 1960

- I Can Get It for You Wholesale – 1962

- Anyone Can Whistle – 1964

- TonyNomination for Best Direction of a Musical

- The Madwoman of Central Park West – 1979

- Tony Awardfor Best Direction of a Musical

- Nick & Nora – 1991

- West Side Story - 1998 Prince Edward theatre London

- Gypsy– 2008 – Tony Award nomination as Best Director of a Musical

- West Side Story – 2009 Broadway Revival

Additional credits

- Anna Lucasta (screenwriter)

- A Clearing in the Woods (playwright)

- Invitation to a March (playwright, director)

- The Madwoman of Central Park West (playwright, director)

- My Good Name (playwright)

- Jolson Sings Again (playwright)

- The Enclave (playwright, director)

- Radical Mystique (playwright, director)

- Big Potato (playwright)

- Two Lives (playwright)

- My Good Name (playwright)

- Claudia Lazlo (playwright)

- Attacks on the Heart (playwright)

- 2 Lives (playwright)

- New Year's Eve (playwright)

- Come Back, Come Back, Wherever You Are (playwright, director)

- Caught (screenwriter)

- Rope (screenwriter)

Accolades

| Year | Award | Category | Work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | Academy Awards | Best Picture | The Turning Point | Nominated | [30] |

| Best Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | Nominated | ||||

| 1957 | British Academy Film Awards | Best British Screenplay | Anastasia | Nominated | [31] |

| 1958 | Bonjour Tristesse

|

Nominated | [32] | ||

| 1975 | Drama Desk Awards | Outstanding Director of a Musical | Gypsy | Won | [33] |

| 1948 | Edgar Allan Poe Awards | Best Motion Picture | Rope | Nominated | [34] |

| 1977 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | The Turning Point | Nominated | [35] |

| 1999 | National Board of Review Awards | Best Screenplay (for career achievement) | — | Won | [36] |

| 1958 | Tony Awards | Best Musical | West Side Story | Nominated | [37] |

| 1960 | Gypsy | Nominated | [38] | ||

| 1968 | Hallelujah, Baby! | Won | [39] | ||

| 1975 | Best Direction of a Musical | Gypsy | Nominated | [40] | |

| 1984 | La Cage aux Folles | Won | [41] | ||

| 2008 | Gypsy | Nominated | [42] | ||

| 1973 | Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Drama – Written Directly for the Screen | The Way We Were | Nominated | [43] |

| 1977 | The Turning Point | Won |

Honors A new award was established in 2010, The Laurents/Hatcher Foundation Award. This is awarded annually "for an un-produced, full-length play of social relevance by an emerging American playwright." The Laurents/Hatcher Foundation will give $50,000 to the writer with a grant of $100,000 towards production costs at a nonprofit theatre. The first award will be given in 2011.[44]

See also

- List of Jewish American playwrights

- List of novelists from the United States

- List of pneumonia victims

- List of people from Brooklyn, New York

- List of playwrights from the United States

- List of theatre directors

References

- ^ a b John M. Clum. The Works of Arthur Laurents: Politics, Love, and Betrayal. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2014.

- ^ "Obituaries: Arthur Laurents". The Daily Telegraph. May 6, 2011.

- ^ a b "When You’re a Shark You’re a Shark All the Way". New York.

- ^ Hawtree, Christopher (May 6, 2011). "Arthur Laurents obituary: Playwright and screenwriter who wrote the book for West Side Story". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- Daily News.

- ^ Arnold, Laurence (May 5, 2011). "Arthur Laurents, Writer of 'West Side Story,' 'Gypsy' Scripts, Dies at 93". Bloomberg News.

- ISBN 1-55783-467-9, pp. 10–11, 34–35.

- ISBN 0-375-40055-9, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Laurents, p. 133.

- ^ Laurents, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Laurents, pp. 22–28.

- ISBN 1604978848

- ^ Clum, John, "The Works of Arthur Laurents: Politics, Love, and Betrayal"

- ^ Laurents, p. 93.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (July 16, 2008). "'West Side Story', This Time With Bilingual Approach, Will Return to Broadway in February 2009" Archived 2008-09-07 at the Wayback Machine. Playbill.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (March 20, 2009). "Our Gangs". The New York Times.

- Seattle Times.

- ^ Laurents, pp. 106–120.

- ^ Laurents, pp. 115–116, 124–131.

- ^ Laurents, p. 136.

- ^ ""West Side Story Author Arthur Laurents Dies, 93" Archived July 9, 2012, at archive.today forum.bcdb.com. May 4, 2011.

- ^ Laurents, p. 29.

- ^ Laurents, pp. 165–190.

- ISBN 0-7679-0420-6.

- ^ "'Look Ma, I'm Dancin' listing". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ Laurents, pp. 286–289.

- ^ "Backstage.com obituary, November 1, 2006". Backstage.

- ^ Berkvist, Robert (May 5, 2011). "Arthur Laurents, Playwright and Director on Broadway, Dies at 93". The New York Times.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (May 6, 2011). "Broadway Lights Will Dim May 6 in Memory of Arthur Laurents" Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Playbill.

- ^ "The 50th Academy Awards (1978) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- BAFTA. 1958. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- BAFTA. 1959. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Nominees and Recipients – 1975 Awards". dramadesk.org. Drama Desk Awards. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Category List – Best Motion Picture". Edgar Awards. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1999 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1958 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "1960 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "1968 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "1975 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "1984 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "2008 Tony Awards". Tony Awards. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (June 3, 2010). "New Award Named for Arthur Laurents and His Partner, the Late Tom Hatcher" Archived June 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Playbill.

Further reading

- Laurents, Arthur (2000). Original Story by Arthur Laurents: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40055-9.

- Laurents, Arthur (2009). Mainly on Directing: Gypsy, West Side Story, and Other Musicals. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-307-27088-2.

- Clum, John (2014). The Works of Arthur Laurents: Politics, Love, and Betrayal. Amherst, NY: ISBN 978-1-60497-884-1.

External links

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |