Chuckanut Formation

| Chuckanut Formation | |

|---|---|

Ma | |

Washington | |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Chuckanut Mountains |

The Chuckanut Formation in northwestern Washington (named after the

Extent

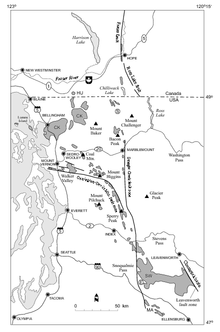

The original Chuckanut/Huntingdon/Swauk formation appears to have been deposited as a single unit in a large basin, and subsequently separated by faulting. The original extent of the formation is unknown, parts having been uplifted and eroded away, and the current extents largely covered by volcanic and glacial deposits. Early work suggested that the marine

Geology

The Chuckanut and related formations "are all composed predominantly of fine- to medium-grained sandstones with lesser amounts of interbedded shale, conglomerate, and coal."[6] The sandstones consist of sand eroded from the Mount Stuart massif and probably from uplifted metamorphic sources in northeastern Washington[7] (this was well before the rise of the Cascade Range), and distributed by rivers across a low-lying coastal plain starting about 54 Ma. These were laid over a metamorphic suite of rocks, those under the Chuckanut now known as the Shuksan, and its correlate under the Swauk known as the Easton.[8] Near Vancouver parts of the Huntingdon Formation lie disconformably on parts of the Cretaceous Nanaimo Group.[9]

Deposition of the Chuckanut continued as convergence of the Crescent Terrane (Olympic Peninsula) initiated strike-slip motion on the Straight Creek Fault (48 Ma), displacing much of the original formation to the north. Continued deposition across the Straight Creek Fault formed the Raging River and Puget Group formations east of Seattle; the former is partly marine, indicating it was probably a large delta, and locating the Eocene coast line.[10] Deposition is believed to have largely ended in the late Eocene (around 42 Ma?[11]) when regional uplift diverted the rivers supplying the sediments, but some deposition may have continued, supplied from local sources.

Johnson (1984) estimated a total thickness of 6,000 metres (20,000 ft), which would make the Chuckanut Formation one of the thickest nonmarine sedimentary sequences in North America. But more recent work suggest that, at least in parts, it may be only 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) thick.[12]

Fossils

Various plant and animal fossils have been found in the Chuckanut Formation. A fossil turtle shell was recovered from the formation at Clark Point in 1960. The specimen was held in the private collection of the finders until 1981 when it was examined at Western Washington University and identified as an indeterminate member of the Testudinoidea superfamily. Reexamination of the fossil in 2000 showed the specimen belongs to the Trionychidae family of soft shelled turtles.[13]

See also

- Geology of the Pacific Northwest

- Fossils

References

- ^ Johnson 1984; Gilley 2003.

- ^ Johnson 1984, p. 101; Mustoe & Gannaway 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Earlier work (see references at Straight Creek Fault) had estimates of up to 190 km.

- ^ Mustoe & Gannaway 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Johnson 1984, p. 102.

- ^ Frizzell 1979, p. viii.

- ^ Johnson 1984, p. 103, Mustoe & Gannaway 1997. p. 4.

- ^ Mustoe & Gannaway 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Gilley 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Vine 1969.

- ^ Johnson 1984, p. 103, fig. 11.

- ^ Mustard & Rouse 1994, p. 132; Mustoe & Gannaway 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Mustoe & Girouard 2001.

- ^ Mustoe 1993.

- ^ Mustoe 2002.

- ^ Mustoe 2002.

Bibliography

- Frizzell, V.A. (1979), Petrology and stratigraphy of Paleogene nonmarine sandstones, Cascade Range, Washington, vol. Open-file Report 79-1149, U.S. Geological Survey, archived from the original on December 14, 2012

- Gilley, B.H.T. (2003), Facies Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Paleogene Huntingdon Formation at Abbotsford, British Columbia [masters thesis] (PDF), Simon Fraser University

- Johnson, S.Y. (1984), "Stratigraphy, age, and paleogeography of the Eocene Chuckanut Formation, northwest Washington", Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 21 (1): 92–106, doi:10.1139/e84-010

- Matthews, R. (2007), Plant macrofossils and palynomorphs from Kanaka Creek, southwestern British Columbia: Paleocene or Eocene?, vol. Cordilleran Section – 103rd Annual Meeting, GSA

- Mustard, P.S.; Rouse, G.E. (1994), "Stratigraphy and evolution of Tertiary Georgia Basin and subjacent Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks, southwestern British Columbia and northwestern Washington State", in Monger, J.W.H. (ed.), Geology and Geological Hazards of the Vancouver Region, Southwestern British Columbia (PDF), vol. Bulletin 481, Geological Survey of Canada, pp. 97–169

- Mustoe, G.E. (1993), "Eocene bird tracks from the Chuckanut Formation, northwest Washington", Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 30 (6): 1205–1208, doi:10.1139/e93-102

- Mustoe, G.E. (2002), "Eocene Bird, Reptile, and Mammal Tracks from the Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington [abstract]", PALAIOS, 17 (4): 403–413,

- Mustoe, G.E.; Gannaway, W.L. (1997), "Paleogeography and Paleontology of the Early Tertiary Chuckanut Formation, Northwest Washington" (PDF), Washington Geology, 25 (3): 3–18

- Mustoe, G.E.; Girouard, S. Jr. (2001), "A fossil trionychid turtle from the early tertiary Chuckanut Formation of Northwestern Washington" (PDF), Northwest Science, 75 (3): 211–218[permanent dead link]

- Vine, James D. (1969), Geology and Coal Resources of the Cumberland, Hobart, and Maple Valley Quadrangles, King County, Washington, vol. Professional Paper 624, U. S. Geological Survey