Conte di Cavour-class battleship

Conte di Cavour at speed in her original configuration

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Conte di Cavour class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Dante Alighieri |

| Succeeded by | Andrea Doria class |

| Built | 1910–1915 |

| In commission | 1914–1955 |

| Completed | 3 |

| Lost | 1 |

| Scrapped | 2 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 176 m (577 ft 5 in) (o/a) |

| Beam | 28 m (91 ft 10 in) |

| Draught | 9.3 m (30 ft 6 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph) |

| Range | 4,800 nmi (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 31 officers and 969 enlisted men |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| General characteristics (after reconstruction) | |

| Displacement | 29,100 long tons (29,600 t) (deep load) |

| Length | 186.4 m (611 ft 7 in) |

| Beam | 33.1 m (108 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) |

| Range | 6,400 nmi (11,900 km; 7,400 mi) at 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) |

| Complement | 1,260 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

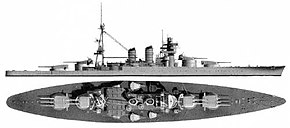

The Conte di Cavour–class battleships were a group of three

Both ships participated in the

Design and description

The Conte di Cavour–class ships were designed by

Taking advantage of the lengthy building times of these ships, other countries were able to build dreadnoughts that were superior in protection and armament,

Basic characteristics

The ships of the Conte di Cavour class were 168.9 meters (554 ft 2 in)

Propulsion

The original machinery for all three ships consisted of three

Armament

As built, the ships' main armament comprised thirteen 46-

The

Armor

The Conte di Cavour-class ships had a complete waterline armor belt that was 2.8 meters (9 ft 2 in) high; 1.6 meters (5 ft 3 in) of this was below the waterline and 1.2 meters (3 ft 11 in) above. It had a maximum thickness of 250 millimeters (9.8 in) amidships, reducing to 130 millimeters (5.1 in) towards the stern and 80 millimeters (3.1 in) towards the bow. The lower edge of this belt was a uniform 170 millimeters (6.7 in) in thickness. Above the main belt was a strake of armor 220 millimeters (8.7 in) thick that extended 2.3 meters (7 ft 7 in) up to the lower edge of the main deck. Above this strake was a thinner one, 130 millimeters thick, that extended 138 meters (452 ft 9 in) from the bow to 'X' turret. The upper strake of armor protected the casemates and was 110 millimeters (4.3 in) thick. The ships had two armored decks: the main deck was 24 mm (0.94 in) thick in two layers on the flat that increased to 40 millimeters (1.6 in) on the slopes that connected it to the main belt. The second deck was 30 millimeters (1.2 in) thick, also in two layers. Fore and aft transverse bulkheads connected the armored belt to the decks.[17]

The frontal armor of the

Modifications and reconstruction

Shortly after the end of World War I, the number of 50-caliber 76 mm guns was reduced to 13, all mounted on the turret tops, and six new

The sisters began an extensive reconstruction program directed by

The center turret and the torpedo tubes were removed and all of the existing secondary armament and AA guns were replaced by a dozen

The deck armor was increased during reconstruction to a total of 135 millimeters (5.3 in) over the engine and boiler rooms and 166 millimeters (6.5 in) over the magazines, although its distribution over three decks, each with multiple layers, meant that it was considerably less effective than a single plate of the same thickness. The armor protecting the barbettes was reinforced with 50-millimeter (2.0 in) plates.[33] All this armor weighed a total of 3,227 long tons (3,279 t).[22]

The existing underwater protection was replaced by the

Ships

| Ship | Namesake | Builder | Laid down[34]

|

Launched[34] | Completed [18] | Fate [35] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conte di Cavour | Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour[36] | La Spezia Arsenale, La Spezia | 10 August 1910 | 10 August 1911 | 1 April 1915 | Sunk during the Battle of Taranto 12 November 1940; salvaged 1941; scrapped 1946 |

| Giulio Cesare | Julius Caesar[37] | Gio. Ansaldo & C., Genoa | 24 June 1910 | 15 October 1911 | 14 May 1914 | Transferred to the Soviet Union, 1949; sank 29 October 1955 after hitting a mine; salvaged and scrapped, 1957 |

| Leonardo da Vinci | Leonardo da Vinci[38] | Odero, Genoa-Sestri Ponente | 18 July 1910 | 14 October 1911 | 17 May 1914 | Sunk by magazine explosion, 2 August 1916; salvaged 1919; sold for scrap, 22 March 1923 [34] |

Service

Conte di Cavour and Giulio Cesare served as

In 1919, Conte di Cavour sailed to North America and visited ports in the United States as well as

Conte di Cavour escorted

Early in World War II, the sisters took part in the Battle of Calabria (also known as the Battle of Punta Stilo) on 9 July 1940, as part of the 1st Battle Squadron, commanded by Admiral Inigo Campioni, during which they engaged major elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet. The British were escorting a convoy from Malta to Alexandria, while the Italians had finished escorting another from Naples to Benghazi, Libya. Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, attempted to interpose his ships between the Italians and their base at Taranto. Crew on the fleets spotted each other in the middle of the afternoon and the Italian battleships opened fire at 15:53 at a range of nearly 27,000 meters (29,000 yd). The two leading British battleships, HMS Warspite and Malaya, replied a minute later. Three minutes after she opened fire, shells from Giulio Cesare began to straddle Warspite which made a small turn and increased speed, to throw off the Italian ship's aim, at 16:00. At that same time, a shell from Warspite struck Giulio Cesare at a distance of about 24,000 meters (26,000 yd). The shell pierced the rear funnel and detonated inside it, blowing out a hole nearly 6.1 meters (20 ft) across. Fragments started several fires and their smoke was drawn into the boiler rooms, forcing four boilers off-line as their operators could not breathe. This reduced the ship's speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). Uncertain how severe the damage was, Campioni ordered his battleships to turn away in the face of superior British numbers and they successfully disengaged.[42] Repairs to Giulio Cesare were completed by the end of August and both ships unsuccessfully attempted to intercept British convoys to Malta in August and September.[43]

On the night of 11 November 1940, Conte di Cavour and Giulio Cesare were at anchor in Taranto harbor when they were attacked by 21

Giulio Cesare participated in the Battle of Cape Spartivento on 27 November 1940, but never got close enough to any British ships to fire at them. The ship was damaged in January 1941 by a near miss during an air raid on Naples; repairs were completed in early February. She participated in the First Battle of Sirte on 17 December 1941, providing distant cover for a convoy bound for Libya, again never firing her main armament.[46] In early 1942, Giulio Cesare was reduced to a training ship at Taranto and later Pola.[45] She steamed to Malta in early September 1943 after the Italian surrender. The German submarine U-596 unsuccessfully attacked the ship in the Gulf of Taranto in early March 1944.[47]

After the war, Giulio Cesare was allocated to the Soviet Union as

Notes

- ^ Friedman provides a variety of sources that show armor-piercing shell weights ranging from 416.92 to 452.32 kilograms (919.16 to 997.2 lb) and muzzle velocities around 861 m/s (2,820 ft/s).[12]

- ^ Sources disagree if Giulio Cesare was fitted with a catapult or not. Giorgerini says both ships were so equipped;[21] Whitley, Bagnasco & Grossman and Bargoni & Gay say that only Conte di Cavour received one.[22][23][24]

Footnotes

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 268–270, 272

- ^ a b Stille, p. 12

- ^ Giorgerini, p. 269

- ^ Giorgerini, p. 270

- ^ a b Giorgerini, pp. 270, 272

- ^ a b c d Fraccaroli, p. 259

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 272–273

- ^ Bargoni & Gay, p. 17

- ^ a b c Hore, p. 175

- ^ Friedman, p. 234

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 276

- ^ Friedman, pp. 233–234

- ^ Bargoni & Gay, p. 14

- ^ a b Campbell, p. 336

- ^ Friedman, pp. 240–241

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 268, 276–277

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 270–271

- ^ a b c Giorgerini, p. 272

- ^ McLaughlin, p. 421

- ^ Giorgerini, pp. 270–272

- ^ a b c Giorgerini, p. 277

- ^ a b c d Whitley, p. 158

- ^ a b c Bagnasco & Grossman, p. 64

- ^ Bargoni & Gay, p. 18

- ^ a b Bargoni & Gay, p. 19

- ^ Brescia, p. 58

- ^ McLaughlin, p. 422

- ^ Bagnasco & Grossman, pp. 64–65

- ^ a b Bagnasco & Grossman, p. 65

- ^ McLaughlin, p. 420

- ^ Campbell, p. 322

- ^ a b Bargoni & Gay, p. 21

- ^ a b McLaughlin, pp. 421–422

- ^ a b c d e f Preston, p. 176

- ^ Brescia, pp. 58–59

- ^ Silverstone, p. 296

- ^ Silverstone, p. 298

- ^ Silverstone, p. 300

- ^ Whitley, pp. 157–158

- ^ a b Whitley, pp. 158–161

- ^ "Bombardment of Corfu". The Morning Bulletin. Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia: National Library of Australia. 1 October 1935. p. 6. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ O'Hara, pp. 28–35

- ^ Whitley, p. 161

- ^ Cernuschi & O'Hara, pp. 81–93

- ^ a b Brescia, p. 59

- ^ Whitley, pp. 161–162

- ^ Rohwer, pp. 272, 298

- ^ McLaughlin, pp. 419, 422–423

References

- Bagnasco, Ermino & de Toro, Augusto (2021). Italian Battleships: Conti di Cavour and Duilio Classes 1911–1956. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-9987-6.

- Bagnasco, Erminio & Grossman, Mark (1986). Regia Marina: Italian Battleships of World War Two: A Pictorial History. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing. ISBN 0-933126-75-1.

- Bargoni, Franco & Gay, Franco (1972). Corazzate classe Conte di Cavour. Roma: Bizzarri. OCLC 34904733.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regia Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Cernuschi, Ernesto & O'Hara, Vincent P. (2010). "Taranto: The Raid and the Aftermath". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2010. London: Conway. pp. 77–95. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1985). "Italy". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 252–290. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Giorgerini, Giorgio (1980). "The Cavour & Duilio Class Battleships". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship IV. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 267–279. ISBN 0-85177-205-6.

- Hore, Peter (2005). Battleships. London: Lorenz Books. ISBN 0-7548-1407-6.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian & Soviet Battleships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-481-4.

- O'Hara, Vincent P. (2008). "The Action off Calabria and the Myth of Moral Ascendancy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2008. London: Conway. pp. 26–39. ISBN 978-1-84486-062-3.

- Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio; et al. (December 2017). "Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918: Part 4: Dreadnought Battleships". Warship International. LIV (4): 307–343. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Stille, Mark (2011). Italian Battleships of World War II. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-831-2.

- ISBN 1-55750-184-X.

Further reading

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1970). Italian Warships of World War I. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0105-3.

External links

- Cavour class – Plancia di Comando

- Conte di Cavour Marina Militare website