Italia-class ironclad

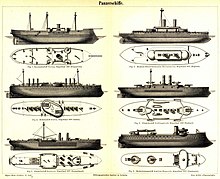

Illustration of Italia c. 1891

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Italia class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Duilio class |

| Succeeded by | Ruggiero di Lauria class |

| Built | 1876–1887 |

| In service | 1885–1921 |

| Completed | 2 |

| Retired | 2 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Type | Ironclad battleship |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 124.7 m (409 ft 1 in) length overall |

| Beam | 22.54 m (74 ft) |

| Draft | 8.75 m (28 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph) |

| Range | 5,000 nautical miles (9,260 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

The Italia class was a

Despite serving for over thirty years, the ships had uneventful careers. They spent their first two decades in service with the Active and Reserve Squadrons, where they were primarily occupied with training maneuvers. Lepanto was converted into a training ship in 1902 and Italia was significantly modernized in 1905–1908 before also becoming a training ship. They briefly saw action during the Italo-Turkish War, where they provided gunfire support to Italian troops defending Tripoli. Lepanto was discarded in early 1915, though Italia continued on as a guard ship during World War I, eventually being converted into a grain transport. She was ultimately broken up for scrap in 1921.

Design

Starting in the 1870s, following the Italian fleet's defeat at the Battle of Lissa, the Italians began a large naval expansion program, at first aimed at countering the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[2] The Italias were the second class of the program, which also included the Duilio class, designed in the early-1870s by Insp Eng Benedetto Brin.[3] The Italia class was ordered by Admiral Simone Antonio Saint-Bon, the Italian naval minister, who envisioned an improved version of the Duilio class that also had the ability to carry large numbers of soldiers, as the Navy had been given the responsibility of defending Italy's lengthy coastline.[4]

Brin prepared the initial design in 1875. The need to keep the size of the ships under control, coupled with developments in

Brin originally planned for the ships to displace 13,850 long tons (14,070 t), to have a main battery of two 450 mm (17.7 in) guns in individual barbettes, a secondary armament of eighteen 149 mm (5.9 in) guns, and to carry 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) of coal for increased range over that of the Duilio class. Brin opted to use open barbettes over the heavy, enclosed gun turrets of the Duilios to save weight, which permitted the addition of a full upper deck. This, in turn, provided the space to carry a division of 10,000 soldiers according to Saint Bon's requirements.[4][6]

As the design evolved, developments in related technologies prompted changes to Brin's design. The development of slow-burning propellants led General Rosset, an artillerist in the Italian Army, suggested that slightly smaller, 432 mm (17 in) guns could be built with longer barrels for the same weight as the 450 mm guns. The longer barrels could take advantage of the slow-burning propellant to increase muzzle velocity, giving the guns better penetrating power. After the original guns were bought by Britain during a war scare with the Russian Empire in 1878, Brin altered the design to incorporate Rosset's ideas. The single 450 mm guns were replaced with pairs of 432 mm guns. By that time, he had made other changes, including reducing the 149 mm armament to eight weapons, and the coal capacity to 1,700 long tons (1,700 t), on 15,000 long tons (15,241 t) displacement. The number of 149 mm guns was reduced because it was found that the additional guns could not have been manned when the 432 mm guns were in use.[6][7]

The ships were authorized in 1875, with funding allocated to begin construction the following year, though design work continued even after they had been laid down in 1876.[4] They were faster and more seaworthy than the preceding Duilio class, owing to their higher freeboard.[8] They were very large and fast warships for their time, displacing over 15,000 tons at full load; Italia could make 17.8 knots (33.0 km/h), while Lepanto could achieve 18.4 knots (34.1 km/h).[5] Other ironclads of the era could not make more than 15 knots (28 km/h).[8] Their high speed, powerful main battery, and thin armor protection has led to some naval historians to characterize the ships as proto-battlecruisers.[9] Designed at a time when the primary threat to capital ships was a slow-firing gun equipped with cast iron shot, the Italias had the poor luck to enter service after quick-firing guns with explosive shells had been developed, rendering their protection scheme useless.[10]

General characteristics

The ships of the Italia class were 122 meters (400 ft) long between perpendiculars and 124.7 m (409 ft) long overall. Italia had a beam of 22.54 m (74 ft), while Lepanto was slightly narrower, at 22.34 m (73.3 ft). The ships had a draft of 8.75 m (28.7 ft) and 9.39 m (30.8 ft), respectively. Italia displaced 13,678 long tons (13,897 t) normally and up to 15,407 long tons (15,654 t) at full load, while Lepanto displaced 13,336 long tons (13,550 t) normally and 15,649 long tons (15,900 t) fully laden.[5] The ships' great size allowed the designers to use very fine hull lines, which gave them high hydrodynamic efficiency and contributed to their speed.[11]

Both ships'

The Italia-class vessels had a minimal

Propulsion machinery

Their propulsion system consisted of four

The ships' propulsion system was projected to produce 18,000

Armament

Italia and Lepanto each carried a main armament of four 432 mm (17 in)

The guns were mounted in pairs

The ships carried a secondary battery of eight medium caliber guns in single

Armor

Instead of belt armor the ships were protected by a

For rest of the ship's protection, recently developed

Modifications

Their secondary batteries were revised over the course of their careers. During a refit in the late 1890s, the ships were given a tertiary battery for close-range defense against torpedo boats. Each ship received twelve 57 mm (2.2 in) Hotchkiss guns and twelve 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss guns in individual mounts. In another refit completed by 1908, Italia had her 150 mm guns replaced with seven 152 mm weapons, and her anti-torpedo boat armament was reduced to six 57 mm guns and two 37 mm guns. The historian Sergei Vinogradov notes that some sources report that two additional torpedo tubes were fitted to Italia at this time, but states that "this seems unlikely." The refit also saw the removal of the central military mast and the installation of two light pole masts.[23]

By 1911, Lepanto had had a second refit as well, which removed all of her 152 mm guns and torpedo tubes and reduced her tertiary battery to nine 57 mm and six 37 mm guns. While serving as a floating battery at Brindisi during World War I, Italia had all of her secondary and tertiary guns removed, and in 1918, when she was converted into a grain transport vessel, her main battery was removed as well, though she received two 120 mm 32-caliber guns for defense.[24]

Construction

| Name | Builder[5] | Laid down[5] | Launched[5] | Completed[5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italia | Regio Cantiere di Castellammare di Stabia | 3 January 1876 | 29 September 1880 | 16 October 1885 |

| Lepanto | Cantiere navale fratelli Orlando | 4 November 1876 | 17 March 1883 | 16 August 1887 |

Service history

Italia and Lepanto spent the first decade of their careers alternative between the Active and Reserve Squadrons of the Italian fleet. Italia served as the

In 1896, both ships began to serve in auxiliary roles, Italia as a gunnery

Lepanto was removed from front-line service in 1902 and converted into a gunnery training ship; to aid in this task, the ship received a variety of light weapons that trainees would go on to use in the fleet. During this period, she also took part in annual training exercises with the rest of the fleet. In October 1910, she was reduced to a barracks ship. Italia was modernized in 1905–1908, losing two of her funnels and several of her small-caliber guns; from 1909 to 1910, she served as a torpedo training ship. She was then used as a barracks ship in 1911.[5][27][32] Both ships were reactivated in September 1911 after the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War, initially assigned to the 5th Division. After the capture of Tripoli in October, Italia and Lepanto were intended to be sent to the city to provide gunfire support for the soldiers defending it,[33] but the plan came to nothing and they remained in Italy.[27]

Lepanto was stricken from the

Notes

- ^ Figures are for Italia

- ^ Greene & Massignani, p. 394.

- ^ Sondhaus 1994, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Vinogradov, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gardiner, p. 341.

- ^ a b c Gibbons, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 49, 53.

- ^ a b c Gibbons, p. 106.

- ^ Sondhaus 2001, p. 112.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Vinogradov, p. 53.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 50–51, 53.

- ^ Vinogradov, p. 51.

- ^ Gibbons, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Vinogradov, p. 59.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 51, 61–62.

- ^ Friedman, p. 231.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 53, 56.

- ^ a b Vinogradov, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Friedman, p. 347.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 57, 59, 64.

- ^ Vinogradov, pp. 57, 59.

- ^ Vinogradov, p. 64.

- ^ Clarke & Thursfield, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b c d Vinogradov, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Garbett 1897, p. 789.

- ^ Garbett 1898, p. 200.

- ^ Brassey, p. 72.

- ^ Garbett 1902, p. 1076.

- ^ a b Gardiner & Gray, p. 255.

- ^ Beehler, pp. 10, 47.

References

- Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 70–80. OCLC 496786828.

- Clarke, George S. & Thursfield, James R. (1897). The Navy and the Nation, or, Naval Warfare and Imperial Defence. London: John Murray. OCLC 640207427.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1897). "Naval Notes". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XLI (232). London: J. J. Keliher & Co.: 779–792. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1898). "Naval Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XLII. London: J. J. Keliher: 199–204. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1902). "Naval and Military Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XLVI. London: J. J. Keliher: 1072–1076. OCLC 8007941.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books, Ltd. ISBN 0-86101-142-2.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-938289-58-6.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21478-5.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-034-9.

- Vinogradov, Sergei (2020). "Italia and Lepanto: Giants of the Iron Century". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 48–66. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

Further reading

- Ordovini, Aldo F.; Petronio, Fulvio & Sullivan, David M. (2015). "Capital Ships of the Italian Royal Navy, 1860–1918, Part 2: Turret/Barbette Ships of the Duilio, Italia and Ruggerio di Lauria Classes". Warship International. LII (4): 326–349. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links

- Italia (1880) Marina Militare website