Culture of Artsakh

Culture of Artsakh includes artifacts of tangible and intangible culture that has been historically associated with

General information

The art and architecture created in

The principal expression of Artsakh's art in the

Works of architecture in Nagorno-Karabakh are constructed according to similar principles and with the use of the same techniques as those in the rest of Armenia.[8][need quotation to verify] Limestone is the principal building materials that form the nucleus for the walls. They are then covered with facing and/or plated with volcanic tuff rock slabs.

In large buildings in cities or in monasteries the exterior facing can consist of carefully cut blocks of tuff. The monasteries of

Names of monasteries in

Historical monuments of the pre-Christian era

The earliest monuments in Artsakh relate to the pre-

In the northeastern outskirts of the

Monasteries, churches and chapels in and around Artsakh

In the early

A number of Christian monuments that are identified with that vital period of the Armenian history belong to the world's oldest places of

While traveling in Artsakh and the neighboring provinces of

For 35 years until his death in 440, Mashtots recruited teams of monks to translate the religious, scientific and literary masterpieces of the ancient world into this new alphabet. Much of their work was conducted in the monastery at Amaras ..."[24]

The description of

Another temple whose history relates to the mission of

The main church of the monastery, reconstructed in 989, consists of one vaulted room (single nave) with an apse on the east flanked by two small rooms.The

Churches with a cupola built on a radiating or cruciform floor plan were numerous in

Another peculiarity of the region is that few of

It was during the post-Seljuk period and the beginning of the

Several monastic churches from this period adopted the model used most widely throughout

Like all Armenian monasteries, those in Artsakh reveal great geometric rigor in the layout of buildings.

A conspicuous characteristic of Armenian monastic architecture of the thirteenth century is the gavit (գավիթ, also called zhamatoun; Armenian: ժամանտուն).[42] The gavits are special square halls usually attached to the western entrance of churches. They were very popular in large monastic complexes where they served as narthexes, assembly rooms and lecture halls, as well as vestibules for receiving pilgrims. Some appear as simple vaulted galleries open to the south (e.g. in the Metz Arrank Monastery; Armenian: Մեծառանից Վանք); others have an asymmetrical vaulted room with pillars (Gtichavank Monastery); or feature a quadrangular room with four central pillars supporting a pyramidal dome (the Dadivank Monastery). In another type of gavit, the vault is supported by a pair of crossed arches – in Horrekavank (Armenian: Հոռեկավանք) and Bri Yeghtze (Armenian: Բռի Եղցէ) monasteries.

The most famous gavit in Nagorno-Karabakh, though, is part of the Gandzasar Monastery. It was built in 1261 and is distinctive for its size and superior quality of workmanship.

The

Although in this period the focus in Artsakh shifted to more complex structures, churches with a single nave continued to be built in large numbers. One example is the monastery of St. Yeghishe Arakyal (Armenian: Սբ. Եղիշե Առաքյալ, also known as the Jrvshtik Monastery (Ջրվշտիկ), which in Armenian means "Longing-for-Water"), in the historical county of Jraberd, that has eight single-naved chapels aligned from north to south. One of these chapels is a site of high importance for the Armenians, as it serves as a burial ground for Artsakh's fifth-century monarch King Vachagan II the Pious Arranshahik. Also known as Vachagan the Pious for his devotion to the Christian faith and support in building a large number of churches throughout the region, King Vachagan is an epic figure whose deeds are immortalized in many of Artsakh's legends and fairytales. The most famous of those tells how Vachagan fell in love with the beautiful and clever Anahit, who then helped the young king defeat pagan invaders.[52]

After an interruption that lasted from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries, architecture flourished again, in the seventeenth century. Many parish churches were built, and the monasteries, serving as bastions of spiritual, cultural and scholarly life, were restored and enlarged. The most notable of those is the Yerits Mankants Monastery ("Monastery of Three Infants," Armenian: Երից Մանկանց Վանք) that was built around 1691 in the county of

Artsakh's architecture of the nineteenth century is distinguished by a merger of innovation and the tradition of grand national monuments of the past. One example is the

In addition to the Cathedral of the Holy Savior, Shusha hosted the Hermitage of Holy Virgins (Armenian: Կուսանաց Անապատ, 1816) and three other Armenian churches: Holy Savior "Meghretsots" (Armenian: Մեղրեցոց Սբ. Ամենափրկիչ, 1838), St. Hovhannes "Kanach Zham" (Armenian: Սբ. Հովհաննես, 1847) and Holy Savior "Aguletsots" (Armenian: Ագուլեցոց Սբ. Ամենափրկիչ, 1882).[55]

In the nineteenth century, several Muslim monuments appear as well. They are linked to the emergence of the Karabakh Khanate, a short-lived, Muslim-ruled principality in Karabakh (1750s–1805). In the city of Shusha, three nineteenth-century mosques were built, which, together with two Russian Orthodox chapels, are the only non-Armenian architectural monuments found on the territories comprising the former Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Region and today's Republic of Artsakh.

Museums in Artsakh

Below is a list of museums that were in Artsakh, which encompasses institutions (including nonprofit organizations, government entities, and private businesses) that collect and care for objects of cultural, artistic, scientific, or historical interest and make their collections or related exhibits available for public viewing. Museums that exist only in cyberspace (i.e., virtual museums) are not included. Also included are non-profit art galleries and exhibit spaces.

Monuments of civil architecture

From the 17th and 18th centuries, several palaces of Armenian

Artsakh's medieval inns (called "idjevanatoun;" Armenian: իջևանատուն) comprise a separate category of civil structures. The best preserved example of those is found near the town of Hadrut.[64]

Before its

Shusha's architecture had its unique style and spirit. That special style synthesized designs used in building grand homes in Artsakh's rural areas (especially in the southern county of Dizak) and elements of neo-classical European architecture. The quintessential example of Shusha's residential dwellings is the house of the Avanesantz family (19th century). Shusha's administrative buildings of note include: Royal College (1875), Eparchial College (1838), Technical School (1881) summer and winter clubs of the City Hall (1896 and 1901), The Zhamharian Hospital (1900), The Khandamirian Theater (1891), The Holy Virgin Women's College (1864) and Mariam Ghukassian Nobility High School (1894). Of these buildings, only Royal College and the Zhamharian Hospital survived the Turko-Muslim attack on the city in 1920.[65]

The best-preserved examples of Artsakh's rural civil architecture are found in historical settlements of Banants (Armenian: Բանանց), Getashen (Armenian: Գետաշեն), Hadrut (Armenian: Հադութ) and Togh (Armenian: Տող).[66]

History of vandalism and destruction

The first record of damage to historical monuments occurred during the early medieval period. During the Armenian-Persian war of 451–484 AD, the Amaras Monastery was wrecked by Persian conquerors who sought to bring pagan practices back to Armenia. Later, In 821, Armenia was overrun by Arabs, and Amaras was plundered. In the same century, however, the monastery was rebuilt under the patronage of Prince Yesai (Armenian: Եսայի Իշխան Առանշահիկ), Lord of Dizak, who bravely fought against the invaders. In 1223, as testified by the Bishop Stephanos Orbelian (died in 1304), Amaras was looted again—at this time, by the Mongols—who took with them St. Grigoris' crosier and a large golden cross decorated with 36 precious stones. According to Orbelian, the wife of the Mongolian leader, Byzantine Princess Despina, proposed to send the cross and the crosier to Constantinople.[67]

In 1387, Amaras and ten other monasteries of Artsakh were attacked by

Shortly after the

The city's three out of five Armenian churches were totally destroyed by the Turkic bands: Holy Savior "Meghretzotz" (Armenian: Մեղրեցոց Սբ. Փրկիչ, built in 1838), Holy Savior "Aguletzotz" (Armenian: Ագուլեցոց Սբ. Փրկիչ, built in 1882) and Hermitage of Holy Virgins (Armenian: Կուսանաց Անապատ, built in 1816).[73] The Cathedral of the Holy Savior (1868–1888) was desecrated and severely damaged. With as many as 7,000 buildings demolished, Shusha has never been restored to its former grandeur. Instead, it shrank, becoming a small town populated by Azerbaijanis(14 thousand residents in 1987 versus 42 thousand in 1913). It stood in ruins from 1920 up to the mid-1960s, when the ruins of the city's Armenian half were bulldozed by orders from Baku and cheaply built apartment complexes were built on top of them.

The

Fortresses, castles and princely palaces

The fortresses of the region (called "berd" in Armenian; բերդ) were usually built on hard-to-reach rocks or on the tips of mountains,using the rugged and heavily forested terrain of the region. Some of the fortresses in Nagorno Karabakh include Jraberd (Armenian: Ջրաբերդ), Handaberd (Armenian: Հանդաբերդ), Kachaghakaberd (Armenian: Կաչաղակաբերդ), Shikakar (Armenian: Շիկաքար), Giulistan (Armenian: Գյուլիստան), Mairaberd (Armenian: Մայրաբերդ), Toghaberd (Armenian: Տողաբերդ), Aknaberd (Armenian: Ակնաբերդ), and Aghjkaberd (Armenian: Աղջկաբերդ). These Castles belonged to Artsakh's aristocratic families, safeguarding their domains against foreign invaders that came from the eastern steppes. The forts were established very early in the history of the region, and each successive generation of their custodians contributed to their improvement.[76]

When the

The Handaberd Castle, the traditional stronghold of the Vakhtangian-Dopian Princes located in Karvachar (Armenian: Քարվաճառ, Azerbaijan's former district of Kelbajar), was rebuilt with a grant received from Cilicia's

Karabakh's most remarkable pieces of fortifications, though, are the Citadel of Shusha and Askeran Fortress. Backed by an intricate system of camps, recruiting centers, watchtowers and fortified beacons, both belonged to the so-called Lesser Syghnakh (Armenian: Փոքր Սղնախ), which was one of Artsakh's two main historical military districts responsible for defending the southern counties of Varanda and Dizak.[79] When the Citadel of Shusha was founded by Panah Ali Khan Javanshir, the founder of the Karabakh Khanate, its walls and other fortifications were built.[80][81]

Khachkars

In the first stage of their evolution, this type of monuments already existed in Artsakh, as attested by one of the earliest dated samples found on the eastern shore of the Lake Sevan (at Metz Mazra, year 881) which at that time was part of the dominion of Artsakh's Princes of Tzar. A very large number of khachkars is also found on the territory of today's Republic of Artsakh and adjacent regions.

Several thirteenth-century examples look particularly refined, and a few of them deserve a special attention for their superior design. The two

Artsakh's most well-known example of embedded

A large khachkar, brought from Artsakh's Metz Arants Hermitage (Armenian: Մեծ Առանց Անապատ) to St. Echmiadzin, represents a rare type of the so-called "winged crosses" which resemble Celtic cross stones from Scotland and Ireland.[83] The largest collection of standing khachkars in Artsakh is in the area called Tsera Nahatak, near the village of Badara.

Lapidary inscriptions

In most cases, facades and walls of Artsakh's churches and monasteries contain engraved texts in Armenian that often provide the precise date of construction, names of patrons and, sometimes, even name of the architect. The number of such texts exceeds several hundred.

Covering the walls of churches and monasteries with ornamented texts in Armenian developed in Artsakh, and in many other places in historical Armenia, into a unique form of decor.

A prominent inscription, for instance, details the foundation of Dadivank's Memorial Cathedral; it covers a large area of the cathedral's southern facade. It begins with the following section:

"By the grace of God Almighty and his only begotten son Jesus Christ, and by the grace of the most Holy Spirit, I, Arzou Hatun, humble servant of the Christ, the daughter of the greatest prince of princes Kurt and the spouse of the Crown Prince Vakhtang, Lord of Haterk and the whole of Upper Khachen, with utmost hope have built this holy cathedral in the place of the last rest of my husband and my two sons … My elder [son] Hasan martyred for his Christian faith in the war against the Turks; and in three months my younger son Grigor died of natural causes and passed to the Christ, leaving his mother in inconsolable mourning. While [my sons] were alive, they vowed to build a church to the glory of God … and I undertook the construction of this expiatory temple with utmost hope and diligence, for the salvation of their souls, and mine and all of my nephews. Thus I plead: while worshipping before the holy altar, remember my prayers inscribed on this church … Completed in the year [modern 1214] of the Armenian Calendar…" [86]

Another historic text inscribed in Armenian is found on the tombstone of St. Grigoris, Bishop of Artsakh, at the

"The tomb of St. Grigoris, Katholicos of Aghvank, grandson of St. Gregory; born in [322 AD], anointed in the year [340 AD], martyred in the year [348 AD] in Derbend, by King Sanesan of the Mazkuts; his holy remains were brought to Amaras by his pupils, deacons from Artsakh." [87]

Fresco art

Few of Artsakh's

The

Illuminated manuscripts

More than thirty known medieval manuscripts originate in Artsakh, Many of which are 13th and 14th century illuminated

During the 12th–15th centuries several dozens of well-known scriptoria functioned in Artsakh and neighboring Utik.[93] The best period of Artsakh's miniature painting may be divided into two main stages. The first one includes the second half of the 12th and the beginning of the 13th centuries. The second stage includes the second half of the 13th century to the beginning of the 14th century. Among the most interesting works of the first stage one can mention the Matenadaran manuscript no. 378, called the Gospel of Prince Vakhtang Khachentsi (produced in 1212), and the Matenadaran manuscript no. 4829, a Gospel produced in 1224 and associated with the name of Princess Vaneni Jajro.[88]

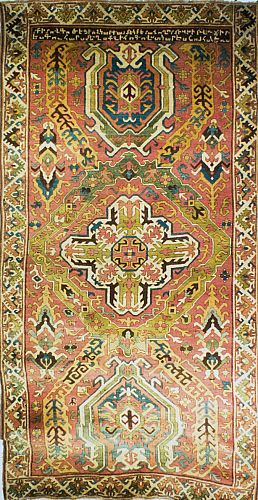

Carpets and rugs

The abundance of rugs produced in the modern period is rooted in this solid ancient tradition. Indeed, recent research has begun to highlight the importance of the Armenian region of Artsakh in the history of a broader group of rugs classified as "Caucasian." Woven works by Artsakh's Armenians come in several types. Rugs in an "eaglebands" (Armenian: արծվագորգ/artzvagorg) or "sunburst" (Armenian: արևագորգ/arevagorg) pattern, a sub-type of Armenian rug featuring dragons, whose manufacturing center from the eighteenth century was Artsakh's county of Jraberd, have characteristically large radiating medallions. Other rugs come with ornaments resembling serpents ("serpentbands;" Armenian: օձագորգ/odzagorg) or clouds with octagonal medallions comprising four pairs of serpents in an "S" shape, and rugs with a series of octagonal, cross-shaped or rhomboid medallions, often bordered by a red band.[94]

Artsakh is also the source of some of the oldest rugs bearing Armenian inscriptions: the rug with three niches from the town of Banants (1602), the rug of Catholicos Nerses of Aghvank (1731), and the famous Guhar (Gohar) Rug (1700).[94] It should also be added that most rugs with Armenian inscriptions come from Artsakh.[95]

See also

- Armenian Cultural Heritage in Azerbaijan

- Culture of Armenia

References

- ^ a b c A. L. Yakobson. From the History of Medieval Armenian Architecture: the Monastery of Gandzasar. In: "Studies in the History of Culture of the Peoples in the East." Moscow-Leningrad. 1960. pp. 140–158 [in Russian].

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991, p. 4-6

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991. p. 4

- ^ ISBN 978-88-85822-25-2

- ISBN 978-1-59886-090-0, p. 28.

- ^ a b Rev. Hamazasp Voskian. The Monasteries of Artsakh, Vienna, 1953, chapter 1

- ISBN 978-88-85822-25-2

- ISBN 978-1-74059-138-6

- ISBN 978-88-85822-25-2

- ^ Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998

- ^ a b Robert H. Hewsen. Armenia: a Historical Atlas, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001, map 10, p. 3

- ^ Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998, p. 45

- ISBN 978-88-85822-25-2, Preamble

- ^ a b Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991, p. 11

- ^ Murad Hasratian. Early Modern Christian Architecture of Armenia. Moscow, Incombook, 2000, p. 5

- ^ Paul Bedoukian. Coinage of the Artaxiads of Armenia, London, 1978, p. 2-14

- ^ a b Walker, Christopher J: "The Armenian presence in mountainous Karabakh," in Transcaucasian Boundaries, John F Wright, Suzanne Goldenberg, Rochard Schofield (eds), (New York, St Martin's Press, 1996), 89–112

- ^ Movses Dasxuranci (1961). The History of the Caucasian Albanians (translated by C. F. J. Dowsett). London: (London Oriental Series, Vol. 8).

- ISBN 978-0-674-39571-8)

- ISBN 978-0-8264-8788-9

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9672120-9-8

- ^ a b Rev. Hamazasp Voskian. The Monasteries of Artsakh, Vienna, 1953, p. 12

- ^ В.А.Шнирельман, "Войны памяти. Мифы, идентичность и политика в Закавказье", М., ИКЦ, "Академкнига", 2003

- ^ National Geographic Magazine. March 2004. p. 43

- ^ Movses Dasxuranci (1961). The History of the Caucasian Albanians (translated by C. F. J. Dowsett). London: (London Oriental Series, Vol. 8), chapters 27–29

- ^ a b Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991

- ^ "Koryun, "Life of Mashtots", translation into Russian and intro by Sh.V.Smbatyan and K.A.Melik-Oghajanyan, Moscow, 1962, footnotes 15–21". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Samvel Karapetian. Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh, Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2001. p. 77

- ^ Volume 21.: Tzitzernavank. Documents of Armenian Art/Documenti di Architettura Armena Series. Polytechnique and the Armenian Academy of Sciences, Milan, OEMME Edizioni; 1989

- ^ Cuneo, P. 'La basilique de Tsitsernavank (Cicernavank) dans le Karabagh,' Revue des Etudes Armeniennes

- ^ Samvel Karapetian. Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh, Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2001, chapter: Tzitzernavank

- ^ Shahen Mkrtchian. Treasures of Artsakh, Yerevan: Tigran Mets Publishing House, 2002, p. 9

- ^ Murad Hasratian. Early Modern Christian Architecture of Armenia. Moscow, Incombook, 2000, p. 22

- ^ Murad Hasratian. Early Modern Christian Architecture of Armenia. Moscow, Incombook, 2000, p. 53

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991, p. 121

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991, p. 87

- ISBN 978-1-74059-138-6, Chapter: Nagorno Karabakh

- ^ ISBN 978-88-85822-25-2, p. 14

- ISBN 978-1-84162-163-0, Dadivank

- ^ Samvel Karapetian. Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh, Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2001, chapter: Dadivank

- ^ Rev. Hamazasp Voskian. The Monasteries of Artsakh, Vienna, 1953, chapter: Dadivank

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry and Patrick Donabedian. Les arts arméniens, Paris, 1987, p. 61

- ^ Volume 17: Gandzasar. Documents of Armenian Art/Documenti di Architettura Armena Series. Polytechnique and the Armenian Academy of Sciences, Milan, OEMME Edizioni; 1987, p. 6

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians, in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chico: 1982, 27–40

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. Armenia: a Historical Atlas, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 80, 119

- ^ George A. Bournoutian. Armenians and Russia, 1626–1796: A Documentary Record. Mazda Publishers, 2001. pp. 49–50

- ^ Rev. Hamazasp Voskian. The Monasteries of Artsakh, Vienna, 1953, chapter: Gandzasar

- ISBN 978-0-9672120-9-8

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry and Patrick Donabedian. Les arts arméniens, Paris, 1987, pp. 34, 35

- Gandzasar

- ^ Volume 1: Haghbat. Documents of Armenian Art/Documenti di Architettura Armena Series. Polytechnique and the Armenian Academy of Sciences, Milan, OEMME Edizioni; 1968

- ^ Robert D San Souci (Author), Raul Colon (Illustrator). Weave Of Words. An Armenian Tale Retold, Orchard Books, 1998

- ^ Shahen Mkrtchian. Treasures of Artsakh, Yerevan: Tigran Mets Publishing House, 2002, chapter: Gandzasar

- ^ Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998, chapter: Monastery of the Three Youths

- ISBN 978-0-9672120-9-8

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "AUA Artsakh Heritage Museums". AUA Artsakh Heritage. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Tours, Barev Armenia. "Historical-Geological Museum of Artsakh | Barev Armenia Tours". barevarmenia.com. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ "Üzeyir Hacıbəyovun Şuşadakı ev muzeyi" (in Azerbaijani). 1905.az. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "MUSEUMS - Karabakh Travel". artsakh.travel. Archived from the original on 2018-04-06. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ "Агрессия против Азербайджана". Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ^ "Azərbaycan Dövlət Qarabağ Tarixi Muzeyi" (in Azerbaijani). 1905.az. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998, p. 79-83

- ^ Artak Ghulyan. Castles/Palaces) of Meliks of Artsakh and Siunik. Yerevan. 2001

- ^ Raffi Kojian, Brady Kiesling. Rediscovering Armenia Guidebook. CD-Rom. HAY-013158. Chapter: Hadrut-Fizuli

- ^ Shahen Mkrtchian. Treasures of Artsakh, Yerevan: Tigran Mets Publishing House, 2002. pp. 3–6

- ^ Samvel Karapetian. Northern Artsakh. Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2004

- ^ Степанос Орбелян, "История области Сисакан", Тифлис, 1910

- ^ Степан Лисицян. Армяне Нагорного Карабаха. Ереван. 1992

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8014-8736-1, pages 50–65

- ^ Walker, Armenia and Karabakh, p.91

- ^ Goldenberg, Pride of Small Nations, p.159

- ^ Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War By Stuart J. Kaufman, p.51

- ^ Caroline Cox (January 1997). "Nagorno Karabakh: forgotten people in a forgotten war". Contemporary Review. "For example, also in the 1920s, Azeris brutally massacred and evicted Armenians from the town of Shusha, which had been a famous and historic centre of Armenian culture"

- ISBN 978-0-9672120-9-8

- ^ Robert Bevan. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. Reaktion Books. 2006, p. 57

- ^ Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998, pp. 50

- ^ Robert Edwards. The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, 1987, p. 73

- ^ Kirakos, Gandzaketsi, 1201–1271. Kirakos Gandzaketsi's history of the Armenians (New York: Sources of the Armenian Tradition, 1986). Gandzaketsi tells the story of friendship between Hetum, King of Cilicia, and Hasan Jalal, Prince of Khachen

- ^ George A. Bournoutian. Armenians and Russia, 1626–1796: A Documentary Record. Mazda Publishers, 2001. The book showcases correspondence and other original documents about military infrastructure of Karabakh and defense activities of the famed Armenian commander Avan Sparapet in the Perso-Ottoman war of the 1720s; see pages 124–129; 143–146, 153–156.

- ^ Mirza Adigozel-bek, Karabakh-name (1845)

- ^ Mirza Jamal Javanshir (1847), History of Karabakh

- ^ Anatoli L. Yakobson. Armenian Khachkars, Moscow, 1986

- ^ a b Jean-Michel Thierry and Patrick Donabedian. Les arts arméniens, Paris, 1987. p. 231

- ^ Rev. Hamazasp Voskian. The Monasteries of Artsakh, Vienna, 1953, chapter 3

- ^ Boris Baratov. Paradise Laid Waste: A Journey to Karabakh, Lingvist Publishers, Moscow, 1998. p. 63-73

- ^ Samvel Karapetian. Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh, Yerevan: Gitutiun Publishing House, 2001, chapter: Dadivank

- ^ Rev. Hamazasp Voskian. The Monasteries of Artsakh, Vienna, 1953, Chapter 1.

- ^ a b c Lydia А. Durnovo, Essays on the Fine Arts of Medieval Armenia. Moscow. 1979.[In Russian]

- ISBN 978-1-84162-163-0

- ^ a b Kirakos, Gandzaketsi, 1201–1271. Kirakos Gandzaketsi's history of the Armenians (New York: Sources of the Armenian Tradition, 1986)

- ^ Hravard Hagopian. The Miniatures of Artsakh and Utik: Thirteenth-Fourteenth Centuries, Yerevan, 1989, p. 136 [In Armenian]

- ^ Hravard Hagopian. The Miniatures of Artsakh and Utik: Thirteenth-Fourteenth Centuries, Yerevan, 1989, p. 137 [In Armenian]

- ^ Jean-Michel Thierry. Eglises et Couvents du Karabagh, Antelais: Lebanon, 1991. p. 63

- ^ a b Lucy Der Manuelian and Murray Eiland. Weavers, Merchants and Kings: The Inscribed Rugs of Armenia, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, 1984

- ^ Lucy Der Manuelian and Murray Eiland. Weavers, Merchants and Kings: The Inscribed Rugs of Armenia, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, 1984, as interpreted as P. Donabedian in The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. Zed Books. 1994. p. 103

Bibliography

- Armenia: 1700 years of Christian Architecture. Moughni Publishers, Yerevan, 2001

- Tom Masters and Richard Plunkett. Georgia, Armenia & Azerbaijan, Lonely Planet Publications; 2 edition (July 2004)

- Nicholas Holding. Armenia with Nagorno Karabagh, Bradt Travel Guides; Second edition (October, 2006)