Culture of Melbourne

The culture of

Traditionally acclaimed as Australia's "cultural capital", Melbourne topped the

Overview

Melbourne hosts and supports many cultural institutions, such as museums, galleries, events, festivals, public/

Arts

Architecture

Melbourne's buildings and structures feature a wide variety of architectural designs, and the city is home to the Royal Exhibition Building, the first Australian building to be listed on the World Heritage Register.[3]

Australia's second oldest architectural firm, and one of the world's oldest, Bates Smart, is based in Melbourne.[4]

Some of Australia's most prolific architects have originated from Melbourne, including

Literature

Melbourne's literary history is rich and diverse. The

In the decades following the gold rush, Melbourne was Australia's undisputed literary capital, famously referred to by

Melbourne's literary publishing sector is the largest in Australia, including the largest number of independent publishers, and presents two of Australia's most significant literary awards: the Victorian Premier's Literary Awards and the Melbourne Prize for Literature. Melbourne is the setting of many significant novels including

The Melbourne Writers Festival was founded in 1986 and is an annual, two-week literary festival that hosts keynotes, panels and workshops by a wide range of local and international guests. Since beginning as a one-day zine fair in 2004, the Emerging Writers' Festival has expanded to ten days of events, workshops, and panel discussions that are focused on the development of writers. Annually across Melbourne there are many local writers’ festivals including the Bayside Literary Festival, Williamstown Literary Festival and Glen Eira Storytelling Festival. In addition to book readings by local authors, many of these events provide opportunities for local writers to develop their skills via workshops and short-story competitions.

In August 2008, Melbourne was the second city in the world to be recognised as a City of Literature by UNESCO—the Wheeler Centre for Books, Writing and Ideas is a literary and publishing centre founded as part of Melbourne's successful bid. As well as programming literary events, debates and awards, the Wheeler Centre hosts literary organisations such as the Melbourne Writers’ Festival, Emerging Writers’ Festival, SPUNC, Australian Poetry, Express Media, Writers Victoria and the Melbourne City of Literature Office.

Opera and theatre

The

The Royal Melbourne Philharmonic was formed in 1853, making it Australia's oldest musical organisation and the only orchestra in Australia to be bestowed "royal" status. The Victoria Orchestra, based in Melbourne, was Australia's first professional orchestra and performed during the period from 1888 to 1891. The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, first assembled in 1906, is now the city's premier orchestra and tours internationally.

There are more theatres and performance venues in Melbourne than any other city in Australia.[

Several professional theatre companies operate in Melbourne, of which the Melbourne Theatre Company, the oldest professional theatre company in Australia, has the most institutional support of any in Australia. There is also a range of smaller professional theatre companies in Melbourne, including the Malthouse, La Mama in Carlton, Cariad Productions, the Red Stitch Actors Theatre, Theatreworks in StKilda and PONYCAM. An array of amateur companies also exist, such as OXAGEN Productions, the Malvern Theatre Company, CLOC, Catchment Players of Darebin, MLOC Productions, Theatrical Incorporated, Altona City Theatre, Windmill Theatre Company and Dandenong Theatre Company.

Comedy

Melbourne is known throughout both Australia and the world as a centre of comedy, with the Melbourne International Comedy Festival listed as one of the three largest stand-up comedy festivals in the world.[14] The city has also produced many of Australia's top-rating comedy television and radio shows,[15] and many of the country's leading comedians either come from the city or have relocated to Melbourne.[16][17][18]

Melbourne-born satirist

Dance events

Melbourne also hosted the 2008 World Latin American Dance Championships.[20] The competition was held in the Vodafone Arena and immediately following the Australian Dancesport Championships. The Australian Dancesport championships will commence on 10 December 2008 and the World Latin Championships will be held on 14 December 2008.

Visual arts

The Melbourne arts scene is vibrant and the city hosts the annual Melbourne International Arts Festival as a celebration of its artistic tradition.

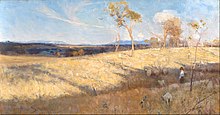

In the 1880s, a group of Melbourne artists formed the first distinctive Australian school of painting.

Modernist

There are more than 100 galleries in Melbourne.

Melbourne is home to a large array of public artworks, statues and sculptures.

The city has major film festivals including the Melbourne International Film Festival, Melbourne Queer Film Festival, Melbourne Underground Film Festival and Melbourne International Animation Festival, featuring several of the city's major cinemas. The Central City Studios in Melbourne Docklands, constructed in 2005, has seen the production of several big budget films.[citation needed]

Melbourne is also known for

Music

Melbourne has one of the most highly regarded live music scenes in the world. In terms of the quality and number of venues, arguably, it is comparable with cities such as Austin. Hundreds of venues throughout Melbourne host live music, some of which host live music every night of the week.

Operatic soprano

In 1934 Clement Williams recorded Let’s Take a Trip to Melbourne, written by Jack O'Hagan.

Melbourne's

Many independent artists from Melbourne have become internationally notable and regularly tour abroad, including:

Melbourne's lively rock and pop music scene has fostered many internationally renowned artists and musicians. The 1960s gave rise to many performers including

More recent notable Melbourne acts include Rogue Traders, Taxiride, Missy Higgins, Madison Avenue, Anthony Callea and The Living End. Melbourne-based television shows Young Talent Time and Neighbours gave many singers a launching pad to international success. Local talents to come from these shows include Kylie Minogue, Dannii Minogue, Tina Arena, Jamie Redfern and Jason Donovan. Another Music TV show that began in Melbourne was Turn It Up! It was first shown on Melbourne's Channel 31 and then relayed via satellite and rebroadcast terrestrially to major TV networks in over 22 countries. The show had the second largest viewing audience around the world, beaten only by the audience of American Bandstand. In one episode, the show presented Melbournes annual festival Moomba to a world audience.

Media

Melbourne has two major daily newspapers, News Corp Australia's Herald Sun and the Nine Entertainment owned The Age. A national Australian newspaper has a Victorian issue and is also published by News Corp. Several weekly magazines are published by News Corp. There are three commercial television networks: Seven, Nine and Ten; and three public: the ABC, SBS and a community television channel, C31. Leader Newspapers is Australia's largest publisher of community newspapers, distributing 33 local papers across Melbourne suburbs.[citation needed] More community newspapers are published by Fairfax Community Newspapers, and the Star News Group.

Melbourne's commercial

Film and drama

Melbourne has been the setting for many

The world's first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, was filmed in Melbourne in 1906.[36] Some of the more famous Australian films include Mad Max and The Castle. Melbourne has also produced many talented film and television actors including Cate Blanchett, Guy Pearce, Eric Bana and is home to Geoffrey Rush.

Australian audiences saw Melbourne portrayed in the 1960s–70s

"Melbourne has little such on-screen cachet. Its skyline barely sticks in the memory. Instead, those architectural aspects that linger are on a far smaller scale: the lacy ironwork that fringes cottages and terrace houses; the unusually broad streets of the central city; the independent cinemas spread across town–the Astor, the Palace, the Sun Theatre–with their gran facades and gently creaking seats."

– Natasha Frost, The New York Times[38]

Sport

In a country that is often labelled 'sports mad', Melbourne has a reputation among Australians for being the national sporting capital.

The city hosts many major sporting events including the

Melbourne is where

During the summer months cricket takes preference amongst Melburnians. In 1877, the world's first

.Melbourne has three

Melbourne is home to 29 stadiums with a capacity of over 10,000 people. Some venues, such as the Albert Park Circuit and Calder Park Raceway, have large capacities but only temporary structures, while there are numerous suburban horse racing tracks and Australian rules football playing fields. In 2000 construction was completed on the Docklands Stadium, capable of seating up to 56,000 people. The stadium was the first in the world to host cricket and Australian football matches under a roof.

The city also has large State Cycling, Hockey, Baseball/Softball and Netball centres, and an Ice centre (National Ice Sports Centre, hosting the Australian Olympic Winter Institute) is being constructed in Docklands.[48]

Melbourne hosted the 2002 World Masters Games; broke new ground as the first city outside the United States to host the World Police and Fire Games in 1995, and the Presidents Cup golf tournament in 1999; and was the first city in the Southern Hemisphere to host the World Polo Championship in 2001. The city has hosted FIFA World Cup qualifiers in both 1997 and 2001.

The Rod Laver Arena was converted into a pool for the 2007 World Aquatics Championships.

Melbourne's skateboarding culture has a lengthy history, with brands such as Globe originating in the city. In 1988, the Australian 60 Minutes program produced a segment that focused solely on Victorian skateboarding. The segment featured Melbourne skateboarding and conducted interviews with notable figures such as the Hill brothers (Stephen, Matt and Mike) and Borgy.[49] X-E-N is a Melbourne skateboard company that was established in 1999 and was co-founded by Andrew and Anthony Mapstone—two figures who, as of August 2012, remain influential in Australian skateboarding.

Recreation and leisure

Melburnians participate in a wide range of recreational and leisure activities.

Australian rules football, Association Football, cricket and netball are popular participation team sports in Melbourne.

Triathlon dominates the Beach Road area during summer, when hundreds of amateurs and professionals dive into Port Phillip Bay on Sundays.

Parks and gardens

Melbourne is noted for its

Entertainment

In Melbourne there are approximately 5000 cafes and restaurants - per capita Melbourne has the most cafes/restaurants in the world.[50] Restaurants are numerous and present a diverse range of cuisines. The city has a reputation as a culinary capital,[51] celebrated by the annual Melbourne Food and Wine Festival. As well as the famous Little Italy of Lygon Street in Carlton, other favourite inner city dining locations for Melburnians include Fitzroy Street St Kilda, Brunswick Street Fitzroy, Victoria Street Collingwood, the CBD, and the Docklands and Southbank precincts. In 2006, Jamie Oliver selected Melbourne as the location for "Fifteen Melbourne", the Australian restaurant for his reality television show Jamie's Kitchen Australia.

Dance music is a thriving part of the Melbourne nightclub and festival scene. National dance music festivals Stereosonic and Future Music both originated in Melbourne. Melbourne is the birthplace of the

Shopping

Shopping or "

Melbourne is home to a number of prominent permanent food and craft markets, the largest and most prominent of which is the Victorian-era

Festivals and events

Melbourne is home to a range of international festivals, most notably the

- The Royal Melbourne Showhas been a Melbourne tradition since 1900.

- The Boxing Day Test has been a Melbourne cricket tradition since 1950.

- Moomba is an annual festival that began in 1955 and celebrates the Yarra River; the Birdman Rally is also a Melbourne tradition.

- Several Melbourne traditions have developed around Australian rules football, particularly the annual AFL Grand Final and the Grand Final Parade

- Anzac Day football event.

- Melbourne Spring Racing Carnival

- Melbourne Fringe Festival

- Midsumma

- Melbourne Queer Film Festival

- Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF)

- Melbourne Underground Film Festival (MUFF)

- Melbourne International Animation Festival (MIAF)

- Melbourne International Comedy Festival

- Melbourne International Singers Festival

- Melbourne Eisteddfod

- Melbourne Winter Masterpieces

- St Kilda Festival

- Melbourne Jazz Festival

- Melbourne Food and Wine Festival

- Melbourne Open House

- Brunswick Street Street Party/Northcote High St Street Party

- Big Day Out Music Festival

- Sydney Road Street Party/Brunswick Music Festival

- Great Australasian Beer SpecTAPular (GABS)

- White Night

Several national traditions originated in Melbourne: The Melbourne Cup has been a Melbourne tradition since 1861 and then became a national tradition, subsequently referred to as "the race that stops the nation"; Carols by Candlelight, first held in 1938, is a Christmas Eve tradition; the Myer Christmas windows are a very popular annual attraction; and the AFL Grand Final attracts hundreds of thousands of spectators, both live and via broadcast media, every year.

There are a number of cultural festivals that celebrate foreign cultures from within the context of the city's culture. Major festivals for Melbourne's large ethnic communities include:

- Greek Antipodes Festival

- Melbourne Italian Festival

- Asian Food Festival

- Australian Chinese New Year

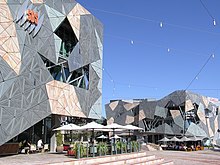

- The Thai Culture and Food Festival, held in Federation Square, is one of the city's most successful festivals; as of 2012, it is in its ninth year.

Parades and protests

The city's wide thoroughfares have become the conduit for the city's parades, marches and rallies. The Victorian State Library lawns are often a staging and starting point for protests and mass gatherings. The steps of the Parliament of Victoria, the Flinders Street Station intersection, Treasury Gardens, Flagstaff Gardens and Federation Square are other such locations for mass gatherings and rallies. Swanston Street and Bourke Street are widely regarded as the civic spines of the city.

Some of the largest demonstrations in the southern hemisphere have taken place in Melbourne:

- Industrial relations demonstration (2005) - more than 100,000 attendees[53]

- Anti-Iraq War demonstration (2003) - more than 100,000 attendees[54]

- Melbourne Vietnam Moratorium (1970) - approximately 100,000 attendees[55]

- Save Live Australian Music (SLAM) rally (2010) - approximately 20,000 attendees[56]

- Melbourne Locked Out 2am Lockout protest (2008) - approximately 10,000 attendees

- Three ‘Change The Rules’ rallies, organised by the trade union movement, leading up to the 2019 Australian Federal Election reportedly attracted 100,000-150,000 attendees on each occasion.[57][58][59]

- School Strike 4 Climate on September 20 2019 reportedly attracted more than 100,000 attendees in Melbourne.[60]

- Invasion Day rallies, which take place annually on January 26 in protest against Australia Day and to highlight Indigenous injustice attract tens of thousands of attendees.

- Black Lives Matter protests on 6 June 2020 also attracted tens of thousands of people despite restrictions put in place because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Trade unionism

Melbourne is regarded as the home of the trade union movement in Australia,[citation needed] with the headquarters of the Australian Council of Trade Unions located in the city;[61] Melbourne is also the birthplace of the Australian "eight-hour day", when the change was introduced into the building industry.[62] Melbourne also has a particularly significant history of strike action.[citation needed]

The

See also

- Culture of Australia

- Media in Melbourne

- List of songs about Melbourne

- List of movies filmed in Melbourne

- List of museums in Melbourne

- Parks and gardens of Melbourne

- Sport in Victoria

- Melbourne street art

- Melbourne performing art venues

References

- ^ "Melbourne, Vancouver top city list". CNN.com. Cable News Network LP, LLLP. 4 October 2002. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Nina Bertok (October 2012). "FEDERATION SQUARE CELEBRATES A DECADE". The Melbourne Review. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens". UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 1992–2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. 2 April 2003. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Ray Edgar (11 February 2004). "Designers front up to world stage". The Age. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "All grown up: a brief history of The Little Bookroom — Kill Your Darlings". www.killyourdarlingsjournal.com. December 2013.

- ^ Miceli, Jacob (February 2008), "A Language of Love", Bookseller and Publisher Magazine, 28, ISSN 0004-8763

- ISBN 9780702223082, p. 140.

- ^ Dirda, Michael (26 March 2014). "Book review: The 1886 'Mystery of a Hansom Cab' has murder and a kitschy charm" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ "The 100 stories which shaped the world". BBC. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "Helen Garner's Monkey Grip (2014)". 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Helen Garner's Monkey Grip". ABC. 1 October 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Richard Gill". Her Majesty's Theatre. May 2007. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Taylor Nelson Sofres; Google Analytics (2007). "Melbourne International Comedy Festival 2007 Marketing Report" (PDF). Melbourne International Comedy Festival 2007. Melbourne International Comedy Festival. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ "Mick Molloy". adams Management. 2012. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "SHAUN MICALLEF". Who Do You Think You Are?. SBS. 27 March 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ David Meagher (6 July 2012). "Best Dressed 2012: Charlie Pickering". The Australian. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- The Daily Telegraph. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Samantha Stayner (21 March 2012). "Barry Humphries and Shaun Micallef". ABC Radio Melbourne. ABC. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Allison Barclay (10 December 2008). "Melbourne plays host to World Latin Championship". Herald Sun. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ISBN 0-19551-554-4, p. 82

- ^ 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved on 12 June 2012.

- ^ Webb, Carolyn (19 April 2011). "Brack's painting stands out from the crowd", The Age. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ "Art Galleries, Melbourne". Visit Melbourne. Tourism Victoria. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Home". Australian Centre for the Moving Image. State Government of Victoria. January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Home". Art Almanac. nextmedia Pty Ltd. January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Home". About Art Almanac. nextmedia Pty Ltd. January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Melbourne Stencil Art Map Archived 9 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Culture in Urban Melbourne". Culture along the streets in Melbourne. 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Modern Australian Fashion Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine from cultureandrecreation.gov.au

- ^ "Street Art". City of Melbourne What's On. City of Melbourne. 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ "Banksy rat destroyed by builders". ABC News. ABC. 16 May 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ National Film and Sound Archive: Does your town have its own song?

- ^ Do That Dance! Australian Post Punk 1977-1983, abc.net.au. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ISBN 0-7119-5601-4.

- ^ The Premier of Victoria Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quinn, Karl (20 February 2013). "Ethan Hawke to make sci-fi film in Melbourne". smh.com.au. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Cultural Cringe and 'The Lost City of Melbourne'". The New York Times. 16 September 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ Transcript of the Prime Minister. The Hon John Howard MP. Address at the launch of the Melbourne Commonwealth Games 2006 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Langmaid, Aaron (28 April 2010). "We're sport's champion city again". Herald Sun. Retrieved on 20 February 2011.

- ^ Cutler, Matt (27 April 2010). "Melbourne retains the SportBusiness ‘Ultimate Sports City’ award" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. SportBusiness. Retrieved on 21 February 2011.

- ^ "We are world's sports capital". Herald Sun. News Limited. 12 November 2006. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ISBN 0-7456-2546-0.

- ^ Sports Attendance, Australia, 2005-06, Australian Bureau of Statistics

- ^ "AFL blueprint for third stadium". Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ MCG Football - A Brief History Archived 23 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Melbourne Cricket Ground. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ISBN 0-2839-9618-8, p. 13

- ^ "Media Release: Melbourne Ice-Sports Centre Consortium Announced".

- ^ Andrew Currie (25 August 2012). "VINTAGE 60 MINUTES SKATE SEGMENT". Skateboarding Australia. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ "Melbourne in Numbers". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Europe on a plate Article from the Adelaide Advertiser

- ^ "Fruit and veg markets in Melbourne". Time Out Melbourne. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Plugin/Engage Media (2005). "Industrial Relations Rally (2005)". Internet Archive. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Andra Jackson (15 February 2003). "Melbourne rallies to the call for peace". The Age. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "THOUSANDS IN MORATORIUM CAMPAIGN TO OPPOSE THE VIETNAM WAR". 80 Days That Changed Our Lives. ABC. 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Home". National SLAM Day. SLAM. 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "100,000 people shut down Melbourne". News.com.au. 9 April 2019.

- TheGuardian.com. 23 October 2018.

- TheGuardian.com. 9 May 2018.

- TheGuardian.com. 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Contact". ACTU - Australian Council of Trade Unions. ACTU. 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Leanne Shingles; Sarah Drechsler (design), Cerise Howard (html and design), Sandy Kirby (content), Luisa Laino (design), Patrick Worsley (management) and Jane Black (research) (2012). "The Eight Hour Day 1856-2006". Eight Hour Day. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "1854 The Eureka Flag". The Migration Heritage Centre. NSW Migration Heritage Centre. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

External links

- That's Me!bourne - Melbourne tourism website

- Arts Victoria

- Melbourne Festival