Delayed onset of lactation

Delayed onset of lactation (DOL) describes the absence of copious

The onset of lactation (OL), also referred to as stage II lactogenesis or secretory activation,[1][4] is one of the three stages of the milk production process.[1] OL is the stage when plentiful production of milk is initiated following the delivery of a full-term infant.[5][6] It is stimulated by an abrupt withdrawal of progesterone and elevation of prolactin levels after the complete expulsion of placenta.[5][6] The other two stages of milk production are stage I lactogenesis and stage III lactogenesis.[1] Stage I lactogenesis refers to the initiation of the mammary glands' synthetic capacity, indicated by the onset of colostrum production that takes place during pregnancy.[1][5] Stage III lactogenesis refers to the continuous supply of mature milk from day nine postpartum, until weaning.[5]

Late-onset of lactogenesis II can be provoked by a variety of pathophysiological, psychological, external and mixed causes.

Diagnosis

Women who experienced delayed OL reports the absence of typical onset signs, including breast swelling, breast heaviness

- A drop in progesterone levels;[8]

- Increase in blood flow, oxygen and glucose uptake;[8]

- A sharp increase in citrate and lactose concentration;[8][9]

- Plasma α-lactalbumin levels peak;[8]and

- Decreased breast milk sodium concentration.[10][11]

Note that delayed onset of lactogenesis II is distinct from low milk supply, where there is a normal onset of lactation, but breast milk is produced in small and insufficient amounts.[12]

Causes and risk factors

Delayed onset of lactation can be a result of various factors including pathophysiological, psychological, external, and mixed factors.[1][5][6]

| Factors | Causes |

|---|---|

| Pathophysiological | |

| Psychological |

|

| External | |

| Mixed |

|

Pathophysiological

Retainment of placental fragments

Retained placenta fragments is an outcome of failure in the complete expulsion of the placenta, and contributes to DOL.[13][17] Residual portions of the placenta continue to secrete progesterone, which inhibits progesterone withdrawal and subsequently hinders the initiation of lactogenesis II.[6][18]

The successful onset of lactation following clearance of placenta fragments has been reported in multiple case studies.[19] The dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure has been reported with dramatic therapeutic effects for mothers experiencing delayed OL due to placenta retainment.[8]

Maternal obesity

Obesity has been reported as a risk factor that has significant associations with DOL,[2][14] although different studies have shown varied conclusions on such connection.[14][20] Relevant reports reveal around one-third of overweight and obese women encountered late arrival of milk, in comparison to approximately one-sixth among women with normal body mass index (BMI).[2][14]

One theory behind delayed copious milk production is that progesterone stored in adipose tissue has led to elevated progesterone levels among obese or overweight women.[20] This interferes with progesterone withdrawal upon the delivery of the placenta and consequently disrupts the activation mechanism of lactogenesis II.[2]

Another theory affiliates delayed lactogenesis II with large breasts, which is typically observed in obese females. Women with large breasts may encounter physical difficulties with latching the infant onto the breast, while the positioning of heavy breasts on an infant's chest may also hamper successful attachment.[14] Unsuccessful attachment may lead to poor infant suckling, which can impede neurohormonal responses and subsequently interrupt the secretion of lactogenic hormones, resulting in delayed secretory activation.[14]

Psychological

Stressful labor and delivery

Maternal stress experienced during labor and delivery can induce DOL.[18] Stress levels can be influenced by factors including the way of labor, duration of labor and degree of post-surgical pain after a cesarean surgery (c-section).[14] Unscheduled cesarean delivery and long labor duration place excessive pressure on the mother and the fetus.[14] In these cases, high perceived pressure raises cortisol levels inside the body.[18][21] The elevated level of the stress hormone affects the secretion of lactogenic hormones in the mother, which delays the onset of lactation.[22]

Women who underwent a c-section are more likely to experience DOL compared to women who delivered vaginally.[14][18] This affiliation could be the result of post-surgical pain and stress associated with emergency c-section or prolonged labor.[14][18] Similarly, a significantly larger proportion of mothers who gave birth by emergency c-section were reported to be unsuccessful on their first attempt at breastfeeding than women who delivered vaginally, or via scheduled c-section.[23]

Maternal stress can also be induced by a protracted separation between mother and infant upon cesarean birth under hospital policies,[17] where the infant has to be transferred to transitional care nursery,[24] or admitted into the neonatal department due to minor illnesses.[24] In both scenarios, the extended period of separation is a significant problem to the initiation of breastfeeding.[17]

External

Ineffective breastfeeding practices

Suboptimal breastfeeding practices of mothers and fetuses also influence the onset of lactation.[15] In particular, exclusive formula-feeding and poor quality of breastfeeding can account for DOL.[15] Mothers whose baby is completely formula-fed from birth may not receive adequate neurohormonal stimulus required for the timely onset of lactation,[25] given that frequent infant suckling is shown to have a stimulatory effect on secretory activation.[25] Meanwhile, breastfeeding quality within the first 48 hours of birth, indicated by signs of successful lactation such as nipple discomfort, is inversely correlated with DOL.[9] This association can be attributed to insufficient nipple stimulation and breast emptying for stimulating lactogenesis II, as a result of low breastfeeding quality.[9]

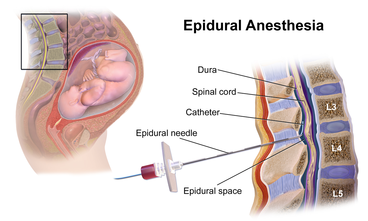

Labor pain medications

Receiving pain-relieving medications during labor increases the chance of mothers experiencing DOL by around 2–3 times, compared to women without medications,

Mixed

Primiparity

Primiparity, or first-time bearing a child, is among the most evident risk factors for the delayed onset.

Associated consequences

The delayed onset of lactation may leave unfavorable outcomes for the mothers and infants like suboptimal infant breastfeeding, behavior excessive neonatal weight loss and shortened duration of breastfeeding.

Suboptimal Infant Breastfeeding Behavior (SIBB)

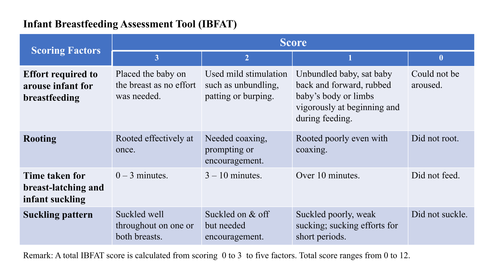

Studies observed that SIBB is prevalent among infants with mothers experiencing delayed copious milk production.[9] In most of these studies, SIBB is indicated with a low Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT) score.[31] This indicates a correlation between DOL with low milk consumption, which can be a cause for inadequate nutritional intake by the infant in the long term, and result in suboptimal growth and development.[9]

Excessive neonatal weight loss

Infant weight loss greater than 10% of initial birth weight during the first 72 hours of life is observed in infants with mothers experiencing DOL.[9] Although neonatal weight loss is a normal physiological process where the infant excretes extra extracellular fluids accumulated pre-birth, it typically should not exceed 10% of birth weight.[7] With delayed OL, excessive weight loss is likely to be an indication and result of ineffective milk transfer, which can subsequently lead to reduced breast milk production due to Feedback Inhibition of Lactation (FIL).[32][7]

Shortened period of breastfeeding

Delayed lactogenesis II is associated with earlier cessation of breastfeeding, and lowered mother confidence in breastmilk production.[14][33] This eventually leads to earlier formula-transitioning.[33] Even though nutrition obtained from formula milk is comparable and sufficient for the normal physical growth of an infant, maternal milk remains the best source of infant nutrition.[34] It has been recommended by the World Health Organization to opt for exclusive breastfeeding until after six months post-delivery, in order to achieve optimal infant health.[35][36] One of the rationales of this suggestion is that formula-milk does not fully support the normal trajectory of fat tissue development, as reflected in the altered body-composition development in formula-fed infants compared to breastfed infants.[37] Formula-feeding is also linked to poor health outcomes in less developed countries, with higher mortality from diarrhea and pneumonia in formula-fed than breastfed babies due to the prevalence of unsanitary preparation, equipment and lack of clean water.[38][39]

Management

When DOL is suspected, intervention should be cause-driven, with a common purpose to improve lactation performance.[8] The strategies include lactation consultation, regular removal of milk from breasts, nipple stimulation or surgical procedures to remove the retained placenta.[citation needed]

Lactation consultation

Mothers experiencing breastfeeding difficulties are often being referred to the

For instance, the consultants provide suck training. It is a special technique aiming to help infants with difficulties in coordinating with the undulation of the tongue to learn proper muscle coordination in breastfeeding.[41] In addition, these trained experts can intervene by supporting mothers in establishing long-term breastfeeding goals, as well as by giving practical assistance in breastfeeding.[40] It is also observed that obese women and women undergoing emergency cesareans are likely not to breastfeed owing to the fear of DOL or breastfeeding failure.[14][42] In such cases, effective and sustained breastfeeding can be initiated under a supportive environment, which can be achieved through providing emotional sessions[40] and informing them about the minimal amounts of colostrum secreted on day one postpartum,[29] to increase their confidence in breastfeeding.[40]

Regular removal of milk and nipple stimulation

Lactation is maintained by routine deposition of milk and nipple stimulation, which triggers prolactin and oxytocin release from the pituitary glands.[6] Women are encouraged to remove the milk from their breasts every two to three hours to maintain a steady milk supply.[8]

Effective ways of emptying the breasts involve breast pumping with a hospital-grade breast pump, for the pumping action promotes complete breast emptying and breast stimulation.[43] This emptying process has to begin at around day three postpartum to increase the chance of successful establishment of lactogenesis.[43][44]

Stimulation of the nipple can also be achieved by means of terminating estrogen treatment and supplementation.[45] Estrogen treatment can diminish nipple sensitivity, which leads to decreased prolactin release.[8] Therefore, pausing estrogen treatment can effectively restore nipple tactile-sensitivity to infant suckling, thereby activating the release of lactogenic hormones.[8][45]

Placental fragment removal

Removal of placental fragments is needed when the placenta cannot be expelled by natural uterine contraction,[13] this can be illustrated with two scenarios that require different treatment methods.

In situations where fragments have been separated from the uterus but yet to be expelled, manual extraction will be performed by directly pulling the detached placenta by hand to bring it outside of the body.[13] Whereas in cases where placental fragments are firmly attached to the wall of the uterus, dilation and curettage is the definitive and therapeutic method of choice.[8] Once the remaining placenta is removed, the mother will be able to restore the expected decline in progesterone level and initiate the onset of lactation.[6][18]

References

- ^ OCLC 1120695924.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ PMID 28060524.

- PMID 28057109.

- ^ S2CID 205073241.

- ^ PMID 25988133.

- ^ PMID 29763156, retrieved 2021-04-01

- ^ a b c Mackay, Karen (2017). "NHS Highland Guidelines for Prevention of Excessive Weight Loss in the Breastfed Neonate" (PDF). NHS Highland. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4377-0788-5, retrieved 2021-04-01

- ^ PMID 20573792.

- S2CID 14061217.

- PMID 29983914.

- ISSN 1016-3360.

- ^ PMID 31632157.

- ^ PMID 31240826.

- ^ S2CID 73456588.

- ^ PMID 24451212.

- ^ )

- ^ S2CID 22282075.

- S2CID 80737449.

- ^ PMID 27330143.

- ^ "Stress effects on the body". www.apa.org. 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- PMID 32756565.

- PMID 27118118.

- ^ PMID 25011378.

- ^ PMID 25589271, retrieved 2021-04-15

- ^ a b c Pregnancy and birth: Epidurals and painkillers for labor pain relief. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). 2018-03-22.

- ^ PMID 20005180.

- ^ Piesesha, Frieska (February 2018). "Maternal Parity and Onset of Lactation on Postpartum Mothers". Health Notions. 2 (2): 249–251 – via Humanistic Network for Science and Technology (HNST).

- ^ S2CID 85456531.

- ^ PMID 25031035.

- ^ PMID 25061006.

- PMID 9513713

- ^ PMID 22575242.

- PMID 27187450.

- ^ "Breastfeeding". www.who.int. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ^ "Breastfeeding in NSW - Promotion, Protection and Support". www1.health.nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2021-04-11.

- PMID 22301930.

- ^ "Improving breastfeeding, complementary foods and feeding practices". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 2019-05-20. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- S2CID 12237910.

- ^ S2CID 26056972.

- ^ )

- PMID 24720501.

- ^ OCLC 920473435.

- S2CID 13812133.

- ^ PMID 28338339.