Dromaeosauroides

| Dromaeosauroides | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of the holotype tooth (DK 315), Geological Museum, Copenhagen

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Clade: | †Eudromaeosauria |

| Subfamily: | †Dromaeosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Dromaeosauroides Christiansen & Bonde, 2003 |

| Type species | |

| †Dromaeosauroides bornholmensis Christiansen & Bonde, 2003

| |

Dromaeosauroides is a

It is known from two teeth, the first of which was found in 2000 and the second in 2008. Based on the first tooth (the

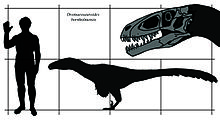

The holotype tooth is 21.7 millimetres (0.85 in) long, and the second tooth is 15 millimetres (0.59 in). They are curved and finely serrated. In life, Dromaeosauroides would have been 2 to 3 metres (7 to 10 ft) in length, and weighed about 40 kilograms (88 lb). As a dromaeosaur it would have been feathered, and had a large sickle claw on its feet like its relatives Dromaeosaurus and

Discovery and naming

Few

During the 1990s, the Fossil Project (disbanded in 2005) was formed by a group of unemployed people who received funding from Denmark and the

The tooth was presented at the 45th annual meeting of the

In late summer 2008, ranger Jens Kofoed found a second dromaeosaurid tooth.[9] This specimen (DK 559) was found in the same location, and later assigned to D. bornholmensis as well.[2] Kofoed explained that the finds were surprising because people had been unsuccessfully searching for dinosaur remains in Denmark for years, and it was like finding a "needle in a haystack".[10] In a press release, the second dromaeosaur tooth was also certified Danekræ by the Natural History Museum of Denmark, which compared the animal to the raptors in the film Jurassic Park, noting that the animals, unlike the film's raptors, would have been feathered.[9]

Since the discovery of Dromaeosauroides, evidence of more dinosaurs has been found on Bornholm. In 2002, a tooth thought to belong to a juvenile

In 2012, Jesper Milàn and colleagues described two coprolites (fossilised faeces) containing fish scales and bones. They were found in the Jydegaard Formation, the first such fossils found in Danish continental Mesozoic deposits. Although the producer of these faeces cannot be identified with certainty, marine turtles and dromaeosaurids such as Dromaeosauroides are the most likely candidates.[17]

Description

Fossil theropod teeth are typically identified according to features including size, proportion, curvature of the crown and the

The tooth is recurved with a backward bend, and is oval in cross-section. Its front and back cutting edges are finely serrated, extending two-thirds down each edge.[8] There are six denticles per millimeter (0.04 in), and each denticle is square and chiseled. The overall form of the tooth, its width and shape in cross-section and its curvature resemble those in the maxilla (upper jawbone) and mandible of the species Dromaeosaurus albertensis from North America. Blood grooves are indistinct or absent, also similar to Dromaeosaurus, and differing from members of the Velociraptorinae subfamily. Dromaeosauroides differs from Dromaeosaurus in that the cutting edge at the front side is further from the middle of the tooth. Although the tooth is larger and the denticles similar, each denticle was smaller than those of Dromaeosaurus, which had only 13–20 denticles per 5 millimetres (0.20 in), instead of Dromaeosauroides' 30.[1] The second known tooth is smaller—15 millimetres (0.59 in)—with the same features as the holotype.[2]

The holotype tooth is roughly 25 percent larger than equivalent Dromaeosaurus teeth, from which a body length of 3 metres (120 in) or more was estimated for Dromaeosauroides; it may have been as long as 3 to 4 metres (9.8 to 13.1 ft).

Classification

Several features of the tooth are only known from members of the family Dromaeosauridae of theropod dinosaurs.[8] Dromaeosauroides was classified as a member of the Dromaeosaurinae subfamily within the Dromaeosauridae, due to its similarity to Dromaeosaurus. Despite the resemblance, Dromaeosauroides is not considered part of that genus. It is unlikely that a genus would survive for 60 million years; Dromaeosauroides lived during the Early Cretaceous, and Dromaeosaurus during the Late Cretaceous. The differences between their denticles also indicate they should be kept separate.[1]

According to Bonde, Dromaeosauroides is one of the oldest known dromaeosaurs in the world; older remains, for the most part, have only tentatively been referred to Dromaeosauridae. Dromaeosauroides was the first definite dromaeosaurid known from the Early Cretaceous of Europe, depending on the identity of

Dromaeosauroides was considered an indeterminate dromaeosaur by Johan Lindgren and colleagues in 2008.

Palaeoenvironment

Only a corner of the Jydegaard Formation is exposed today; the remainder is overgrown. Jydegaard is part of the

The fish and bivalves were found in clay which was probably a lagoon, and the dinosaurs and lizards in sand which probably was land, perhaps a beach; turtles and crocodiles were found in both. Freshwater snails were found in clay that may have been shallow, drying lakes behind a sandy barrier between lagoon and sea, in a setting perhaps similar to the Florida Keys or the southwestern coast of Jutland.[2] Dinosaurs may have fed there, based on the remains of plants and small land animals, and theropods may have hunted along the shore.[1] Bornholm and Scania appear to be the only places were remains of the Scandinavian-Russian fauna of the Early Cretaceous can be found. Further investigations there may show whether this fauna has European or Asian affinities.[2]

Based on possible dromaeosaur coprolites from the Jydegaard Formation, which contained scales of the fish Lepidotes, Milàn and colleagues speculated that some dromaeosaurids were able to catch fish with the enlarged sickle claw on the second digit of the foot, similar to the "spear fishing" that has been proposed for the theropod

See also

References

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 9780253005700.

- ^ Estrup, E. J. (2007). "Jurassic Park Denmark" (PDF). Scient. 4 (in Danish). 1: 12–14.[dead link]

- ^ Bonde, N. (2001). "A Berriasian "Wealden fauna" from Bornholm, Denmark". Palaeontological Association 45th Annual Meeting. 4.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ISBN 978-0-517-46890-6.

- ^ ISBN 9788702049855.

- ^ a b "Sensationelt dinosaurfund på Bornholm" (in Danish). Jyllands-Posten. 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-06-16.

- ^ Barslev, K. (2008). "Tand fra dinosaur fundet på Bornholm" (in Danish). Kristeligt Dagblad. Archived from the original on 2012-08-30.

- ^ .

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2013-11-05.

- .

- S2CID 129740267.

- .

- ^ a b Milàn, J.; Rasmussen, B. W.; Bonde, N. (2012). "Coprolites with prey remains and traces from coprophagous organisms from the Lower Cretaceous (Late Berriasian) Jydegaard Formation of Bornholm, Denmark" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Bulletin. 57: 235–240. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ^ Ejsing, J. (2003). "Fortidsmonstre ser dagens lys" (in Danish). Berlingske. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- .

- S2CID 245324247.

- ISBN 9783899370539.