Dusky shark

| Dusky shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. obscurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus obscurus (Lesueur, 1818)

| |

| |

| Confirmed (dark blue) and suspected (light blue) range of the dusky shark[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharhinus iranzae Fourmanoir, 1961 *ambiguous synonym | |

The dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus) is a

Adult dusky sharks have a broad and varied diet, consisting mostly of

Because of its slow reproductive rate, the dusky shark is very vulnerable to human-caused population depletion. This species is highly valued by commercial fisheries for its fins, used in shark fin soup, and for its meat, skin, and liver oil. It is also esteemed by recreational fishers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Endangered worldwide and Vulnerable off the eastern United States, where populations have dropped to 15–20% of 1970s levels. The dusky shark is regarded as potentially dangerous to humans due to its large size, but there are few attacks attributable to it.

Taxonomy

French

Many early sources gave the scientific name of the dusky shark as Carcharias (later Carcharhinus) lamiella, which originated from an 1882 account by David Starr Jordan and Charles Henry Gilbert. Although Jordan and Gilbert referred to a set of jaws that came from a dusky shark, the type specimen they designated was later discovered to be a copper shark (C. brachyurus). Therefore, C. lamiella is not considered a synonym of C. obscurus but rather of C. brachyurus.[4][6] Other common names for this species include bay shark, black whaler, brown common gray shark, brown dusky shark, brown shark, common whaler, dusky ground shark, dusky whaler, river whaler, shovelnose, and slender whaler shark.[7]

Phylogeny and evolution

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships of the dusky shark, based on allozyme sequences.[8] |

Teeth belonging to the dusky shark are fairly well represented in the

In 1982,

Distribution and habitat

The range of the dusky shark extends worldwide, albeit discontinuously, in tropical and warm-temperate waters. In the western Atlantic Ocean, it is found from Massachusetts and the

Residing off continental coastlines from the

The dusky shark is nomadic and strongly migratory, undertaking recorded movements of up to 3,800 km (2,400 mi); adults generally move longer distances than juveniles. Sharks along both coasts of North America shift northward with warmer summer temperatures, and retreat back towards the equator in winter.[1] Off South Africa, young males and females over 0.9 m (3.0 ft) long disperse southward and northward respectively (with some overlap) from the nursery area off KwaZulu-Natal; they join the adults several years later by a yet-unidentified route. In addition, juveniles spend spring and summer in the surf zone and fall and winter in offshore waters, and as they approach 2.2 m (7.2 ft) in length begin to conduct a north-south migration between KwaZulu-Natal in the winter and the Western Cape in summer. Still-larger sharks, over 2.8 m (9.2 ft) long, migrate as far as southern Mozambique.[1][5][19] Off Western Australia, adult and juvenile dusky sharks migrate towards the coast in summer and fall, though not to the inshore nurseries occupied by newborns.[1]

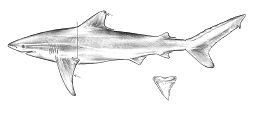

Description

One of the largest members of its genus, the dusky shark commonly reaches a length of 3.2 m (10 ft) and a weight of 160–180 kg (350–400 lb); the maximum recorded length and weight are 4.2 m (14 ft) and 372 kg (820 lb) respectively.[7][20][21] However, the maximum reported size of the species is 4.5 m (15 ft), while the maximum weight is reported to reach up to 500 kg (1,100 lb).[22] Females grow larger than males.[23] This shark has a slender, streamlined body with a broadly rounded snout no longer than the width of the mouth. The nostrils are preceded by barely developed flaps of skin. The medium-sized, circular eyes are equipped with nictitating membranes (protective third eyelids). The mouth has very short, subtle furrows at the corners and contains 13-15 (typically 14) tooth rows on either side of both jaws. The upper teeth are distinctively broad, triangular, and slightly oblique with strong, coarse serrations, while the lower teeth are narrower and upright, with finer serrations. The five pairs of gill slits are fairly long.[20]

The large

Biology and ecology

As an

Full-grown dusky sharks have no significant natural predators.

Feeding

The dusky shark is a generalist that takes a wide variety of prey from all levels of the water column, though it favors hunting near the bottom.[25][40] A large individual can consume over a tenth of its body weight at a single sitting.[41] The bite force exerted by a 2 m (6.6 ft) long dusky shark has been measured at 60 kg (130 lb) over the 2 mm2 (0.0031 in2) area at the tip of a tooth. This is the highest figure thus far measured from any shark, though it also reflects the concentration of force at the tooth tip.[42] Dense aggregations of young sharks, forming in response to feeding opportunities, have been documented in the Indian Ocean.[1]

The known diet of the dusky shark encompasses

In the northwestern Atlantic, around 60% of the dusky shark's diet consists of bony fishes, from over ten families with

Life history

Like other requiem sharks, the dusky shark is

With a

| Region | Male length and age at maturity | Female length and age at maturity |

|---|---|---|

| Northwestern Atlantic | 2.80 m (9.2 ft), 19 years[23] | 2.84 m (9.3 ft), 21 years[23] |

| Eastern South Africa | 2.80 m (9.2 ft), 19–21 years[4][49][50] | 2.60–3.00 m (8.53–9.84 ft), 17–24 years[4][49] |

| Indonesia | 2.80–3.00 m (9.19–9.84 ft), age unknown[51] | 2.80 m (9.2 ft), age unknown[51] |

| Western Australia | 2.65–2.80 m (8.7–9.2 ft), 18–23 years[25][52] | 2.95–3.10 m (9.7–10.2 ft), 27–32 years[25][53] |

Newborn dusky sharks measure 0.7–1.0 m (2.3–3.3 ft) long;

Human interactions

Danger to humans

The dusky shark is considered to be potentially dangerous to humans because of its large size, though little is known of how it behaves towards people underwater.[5] As of 2009, the International Shark Attack File lists it as responsible for six attacks on people and boats, three of them unprovoked and one fatal.[56] However, attacks attributed to this species off Bermuda and other islands were probably in reality caused by Galapagos sharks.[5]

Shark nets

Shark nets used to protect beaches in South Africa and Australia entangle adult and larger juvenile dusky sharks in some numbers. From 1978 to 1999, an average of 256 individuals were caught annually in nets off KwaZulu-Natal; species-specific data is not available for nets off Australia.[54]

In aquariums

Young dusky sharks adapt well to display in public aquariums.[5]

Fishing

The dusky shark is one of the most sought-after species for shark fin trade, as its fins are large and contain a high number of internal rays (ceratotrichia).[54] In addition, the meat is sold fresh, frozen, dried and salted, or smoked, the skin is made into leather, and the liver oil is processed for vitamins.[7] Dusky sharks are taken by targeted commercial fisheries operating off eastern North America, southwestern Australia, and eastern South Africa using multi-species longlines and gillnets. The southwestern Australian fishery began in the 1940s and expanded in the 1970s to yield 500–600 tons per year. The fishery utilizes selective demersal gillnets that take almost exclusively young sharks under three years old, with 18–28% of all newborns captured in their first year. Demographic models suggest that the fishery is sustainable, provided that the mortality rate of sharks under 2 m (6.6 ft) long is under 4%.[54]

In addition to commercial shark fisheries, dusky sharks are also caught as bycatch on longlines meant for tuna and swordfish (and usually kept for its valuable fins), and by recreational fishers. Large numbers of dusky sharks, mostly juveniles, are caught by sport fishers off South Africa and eastern Australia. This shark was once one of the most important species in the Florida trophy shark tournaments, before the population collapsed.[54]

Conservation

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Endangered worldwide. The American Fisheries Society has assessed North American dusky shark populations as Vulnerable.[20] Its very low reproductive rate renders the dusky shark extremely susceptible to overfishing.

Stocks off the eastern United States are severely overfished; a 2006 stock assessment survey by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) showed that its population had dropped to 15–20% of 1970s levels. In 1997, the dusky shark was identified as a

The New Zealand Department of Conservation has classified the dusky shark as "Migrant" with the qualifier "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[60]

References

- ^ . Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-12072-0.

- ^ Lesueur, C.A. (May 1818). "Description of several new species of North American fishes (part 1)". Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 1 (2): 222–235.

- ^ ISBN 0-520-22265-2.

- ^ ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- .

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2009). "Carcharhinus obscurus" in FishBase. May 2009 version.

- ^ S2CID 39697113.

- ^ a b Heim, B. and Bourdon, J. (April 20, 2009). Species from the Fossil Record: Carcharhinus obscurus. The Life and Times of Long Dead Sharks. Retrieved on April 29, 2010.

- S2CID 87154947.

- S2CID 128469722.

- ISBN 978-1-56164-409-4.

- S2CID 130609225.

- S2CID 86113934.

- ^ Garrick, J.A.f. (1982). Sharks of the genus Carcharhinus. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS Circ. 445: 1–194.

- ISBN 0-691-08453-X.

- PMID 19216767.

- ^ Hoffmayer, E.R., Franks, J.S., Driggers, W.B. (III) and Grace, M.A. (March 26, 2009). "Movements and Habitat Preferences of Dusky (Carcharhinus obscurus) and Silky (Carcharhinus falciformis) Sharks in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: Preliminary Results." 2009 MTI Bird and Fish Tracking Conference Proceedings.

- ^ ISBN 1-86825-394-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Knickle, C. Biological Profiles: Dusky Shark. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on May 18, 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- ISBN 978-1-86513-106-1.

- ^ a b c Natanson, L.J.; Casey, J.G. & Kohler, N.E. (1995). "Age and growth estimates for the dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, in the western North Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 93 (1): 116–126.

- ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- ^ Huish, M.T.; Benedict, C. (1977). "Sonic tracking of dusky sharks in Cape Fear River, North Carolina". Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society. 93 (1): 21–26.

- ^ Schwartz, F.J. (Summer 2004). "Five species of sharksuckers (family Echeneidae) in North Carolina". Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science. 120 (2): 44–49.

- S2CID 1226830.

- S2CID 6769785.

- S2CID 944343.

- JSTOR 3270938.

- ^ Knoff, M.; De Sao Clemente, S.C.; Pinto, R.M.; Lanfredi, R.M.; Gomes, D.C. (April–June 2004). "New records and expanded descriptions of Tentacularia coryphaenae and Hepatoxylon trichiuri homeacanth trypanorhynchs (Eucestoda) from carcharhinid sharks from the State of Santa Catarina off-shore, Brazil". Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria. 13 (2): 73–80.

- S2CID 31178927.

- S2CID 85621860.

- ^ MacCullum, G.A. (1917). "Some new forms of parasitic worms". Zoopathologica. 1 (2): 1–75.

- ^ Yamauchi, T.; Ota, Y.; Nagasawa, K. (August 20, 2008). "Stibarobdella macrothela (Annelida, Hirudinida, Piscicolidae) from Elasmobranchs in Japanese Waters, with New Host Records". Biogeography. 10: 53–57.

- ^ a b Newbound, D.R.; Knott, B. (November 1999). "Parasitic copepods from pelagic sharks in Western Australia". Bulletin of Marine Science. 65 (3): 715–724.

- ^ Jensen, C.; Schwartz, F.J. (December 1994). "Atlantic Ocean occurrences of the sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus (Petromyzontiformes: Petromyzontidae), parasitizing sandbar, Carcharhinus plumbeus, and dusky, C. obscurus (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae), sharks off North and South Carolina". Brimleyana. 21: 69–76.

- ^ Martin, R.A. A Place For Sharks. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on May 5, 2010.

- ^ S2CID 21850377.

- ^ .

- ^ Martin, R.A. The Power of Shark Bites. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on August 31, 2009.

- ^ Gubanov, E.P. (1988). "Morphological characteristics of the requiem shark, Carcharinus obscurus, of the Indian Ocean". Journal of Ichthyology. 28 (6): 68–73.

- ^ "Carcharhinus obscurus (Shovelnose)". Animal Diversity Web.

- doi:10.1071/MF01017.

- ^ .

- S2CID 86281315.

- S2CID 25172842.

- ^ .

- S2CID 85181390.

- ^ .

- ^ doi:10.1071/MF01131.

- ^ McAuley, R.; Lenanton, R.; Chidlow, J.; Allison, R.; Heist, E. (2005). "Biology and stock assessment of the thickskin (sandbar) shark, Carcharhinus plumbeus, in Western Australia and further refinement of the dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, stock assessment. Final FRDC Report - Project 2000/134" (PDF). Fisheries Western Australia Fisheries Research Report. 151: 1–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-28. Retrieved 2016-11-11.

- ^ ISBN 2-8317-0700-5.

- ^ Simpfendorfer, C.A. (Oct 2000). "Growth rates of juvenile dusky sharks, Carcharhinus obscurus (Lesueur, 1818), from southwestern Australia estimated from tag-recapture data". Fishery Bulletin. 98 (4): 811–822.

- ^ ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark. International Shark Attack File, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Retrieved on May 14, 2010.

- NOAA

- ^ Species of Concern: Dusky Shark Archived 2010-08-03 at the Wayback Machine. (Jan. 6, 2009). NMFS Office of Protected Resources. Retrieved on May 18, 2009.

- S2CID 11342367.

- OCLC 1042901090.