Marine mammal

Marine mammals are

. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine environments for feeding and survival.Marine mammal adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle varies considerably between species. Both cetaceans and sirenians are fully aquatic and therefore are obligate water dwellers. Pinnipeds are semiaquatic; they spend the majority of their time in the water but need to return to land for important activities such as

Marine mammals were first hunted by

Taxonomy

Classification of extant species

| Phylogeny of marine mammals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The taxa in bold are marine. Taxa indicated with a † symbol are recently extinct.[1] |

- Order Cetartiodactyla[2]

- Suborder Whippomorpha

- Family Balaenidae (right and bowhead whales), two genera and four species

- Family Cetotheriidae (pygmy right whale), one species

- Family Balaenopteridae(rorquals), two genera and eight species

- Family Eschrichtiidae (gray whale), one species

- Family Physeteridae (sperm whale), one species

- Family Kogiidae (pygmy and dwarf sperm whales), one genus and two species

- Family Monodontidae (narwhal and beluga), two genera and two species

- Family Ziphiidae(beaked whales), six genera and 21 species

- Family Delphinidae(oceanic dolphins), 17 genera and 38 species

- Family Phocoenidae(porpoises), two genera and seven species

- Suborder Whippomorpha

- Order Sirenia (sea cows)[2]

- Family Trichechidae (manatees), three species

- Family Dugongidae (dugongs), one species

- Order Carnivora (carnivores)[2]

- Suborder Caniformia

- Family Mustelidae, two species

- Family Ursidae(bears), one species

- Suborder Pinnipedia (sealions, walruses, seals)

- Family Otariidae (eared seals), seven genera and 15 species

- Family Odobenidae (walrus), one species

- Family Phocidae (earless seals), 14 genera and 18 species

- Suborder Caniformia

The term "marine mammal" encompasses all mammals whose survival depends entirely or almost entirely on the oceans, which have also evolved several specialized aquatic traits. In addition to the above, several other mammals have a great dependency on the sea without having become so anatomically specialized, otherwise known as "quasi-marine mammals". This term can include: the

Evolution

Marine mammals form a diverse group of 129 species that rely on the ocean for their existence.[4][5] They are an informal group unified only by their reliance on marine environments for feeding.[6] Despite the diversity in anatomy seen between groups, improved foraging efficiency has been the main driver in their evolution.[7][8] The level of dependence on the marine environment varies considerably with species. For example, dolphins and whales are completely dependent on the marine environment for all stages of their life; seals feed in the ocean but breed on land; and polar bears must feed on land.[6]

The cetaceans became aquatic around 50 million years ago (mya).

Sirenians, the sea cows, became aquatic around 40 million years ago. The first appearance of sirenians in the fossil record was during the early Eocene, and by the late Eocene, sirenians had significantly diversified. Inhabitants of rivers, estuaries, and nearshore marine waters, they were able to spread rapidly. The most primitive sirenian, †Prorastomus, was found in Jamaica,[8] unlike other marine mammals which originated from the Old World (such as cetaceans[16]). The first known quadrupedal sirenian was †Pezosiren from the early middle Eocene.[17] The earliest known sea cows, of the families †Prorastomidae and †Protosirenidae, were both confined to the Eocene, and were pig-sized, four-legged, amphibious creatures.[18] The first members of Dugongidae appeared by the middle Eocene.[19] At this point, sea cows were fully aquatic.[18]

Pinnipeds

Fossil evidence indicates the sea otter (Enhydra) lineage became isolated in the North Pacific approximately two mya, giving rise to the now-extinct †

Polar bears are thought to have diverged from a population of

In general, terrestrial amniote invasions of the sea have become more frequent in the Cenozoic than they were in the Mesozoic. Factors contributing to this trend include the increasing productivity of near-shore marine environments, and the role of endothermy in facilitating this transition.[29]

Distribution and habitat

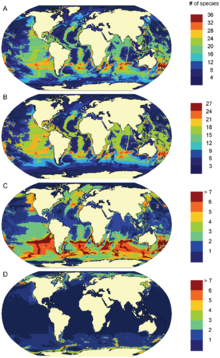

Marine mammals are widely distributed throughout the globe, but their distribution is patchy and coincides with the productivity of the oceans.[31] Species richness peaks at around 40° latitude, both north and south. This corresponds to the highest levels of primary production around North and South America, Africa, Asia and Australia. Total species range is highly variable for marine mammal species. On average most marine mammals have ranges which are equivalent or smaller than one-fifth of the Indian Ocean.[32] The variation observed in range size is a result of the different ecological requirements of each species and their ability to cope with a broad range of environmental conditions. The high degree of overlap between marine mammal species richness and areas of human impact on the environment is of concern.[4]

Most marine mammals, such as seals and sea otters, inhabit the coast. Seals, however, also use a number of terrestrial habitats, both continental and island. In temperate and tropical areas, they

Many marine mammals seasonally migrate. Annual ice contains areas of water that appear and disappear throughout the year as the weather changes, and seals migrate in response to these changes. In turn, polar bears must follow their prey. In

Adaptations

Marine mammals have a number of

Marine mammals are able to dive for long periods. Both pinnipeds and cetaceans have large and complex blood vessel systems pushing large volumes of blood rich in myoglobin and hemoglobin, which serve to store greater quantities of oxygen. Other important reservoirs include muscles and the spleen which all have the capacity to hold a high concentration of oxygen. They are also capable of bradycardia (reduced heart rate), and vasoconstriction (shunting most of the oxygen to vital organs such as the brain and heart) to allow extended diving times and cope with oxygen deprivation.[31] If oxygen is depleted (hypoxia), marine mammals can access substantial reservoirs of glycogen that support anaerobic glycolysis.[43][44][45]

Sound travels differently through water, and therefore marine mammals have developed adaptations to ensure effective communication, prey capture, and predator detection.[46] The most notable adaptation is the development of echolocation in whales and dolphins.[31] Toothed whales emit a focused beam of high-frequency clicks in the direction that their head is pointing. Sounds are generated by passing air from the bony nares through the phonic lips.[47]: p. 112 These sounds are reflected by the dense concave bone of the cranium and an air sac at its base. The focused beam is modulated by a large fatty organ known as the 'melon'. This acts like an acoustic lens because it is composed of lipids of differing densities.[47]: 121 [48]

Marine mammals have evolved a wide variety of features for feeding, which are mainly seen in their dentition. For example, the cheek teeth of pinnipeds and odontocetes are specifically adapted to capture fish and squid. In contrast,

Polar bears, otters, and

Ecology

Dietary

All cetaceans are

Baleen whales use their baleen plates to sieve plankton, among others, out of the water; there are two types of methods: lunge-feeding and gulp-feeding. Lunge-feeders expand the volume of their jaw to a volume bigger than the original volume of the whale itself by inflating their mouth. This causes grooves on their throat to expand, increasing the amount of water the mouth can store.[56][57] They ram a baitball at high speeds in order to feed, but this is only energy-effective when used against a large baitball.[58] Gulp-feeders swim with an open mouth, filling it with water and prey. Prey must occur in sufficient numbers to trigger the whale's interest, be within a certain size range so that the baleen plates can filter it, and be slow enough so that it cannot escape.[59]

Otters are the only marine animals that are capable of lifting and turning over rocks, which they often do with their front paws when searching for prey.[60] The sea otter may pluck snails and other organisms from kelp and dig deep into underwater mud for clams.[60] It is the only marine mammal that catches fish with its forepaws rather than with its teeth.[61] Under each foreleg, sea otters have a loose pouch of skin that extends across the chest which they use to store collected food to bring to the surface. This pouch also holds a rock that is used to break open shellfish and clams, an example of tool use.[62] The sea otters eat while floating on their backs, using their forepaws to tear food apart and bring to their mouths.[63][64] Marine otters mainly feed on crustaceans and fish.[65]

Pinnipeds mostly feed on fish and

The polar bear is the most carnivorous species of bear, and its diet primarily consists of ringed (Pusa hispida) and bearded (Erignathus barbatus) seals.[67] Polar bears hunt primarily at the interface between ice, water, and air; they only rarely catch seals on land or in open water.[68] The polar bear's most common hunting method is still-hunting:[69] The bear locates a seal breathing hole using its sense of smell, and crouches nearby for a seal to appear. When the seal exhales, the bear smells its breath, reaches into the hole with a forepaw, and drags it out onto the ice. The polar bear also hunts by stalking seals resting on the ice. Upon spotting a seal, it walks to within 100 yards (90 m), and then crouches. If the seal does not notice, the bear creeps to within 30 to 40 feet (9 to 10 m) of the seal and then suddenly rushes to attack.[70] A third hunting method is to raid the birth lairs that female seals create in the snow.[69] They may also feed on fish.[71]

Sirenians are referred to as "sea cows" because their diet consists mainly of seagrass. When eating, they ingest the whole plant, including the roots, although when this is impossible they feed on just the leaves.[72] A wide variety of seagrass has been found in dugong stomach contents, and evidence exists they will eat algae when seagrass is scarce.[73] West Indian manatees eat up to 60 different species of plants, as well as fish and small invertebrates to a lesser extent.[74]

Keystone species

Sea otters are a classic example of a keystone species; their presence affects the ecosystem more profoundly than their size and numbers would suggest. They keep the population of certain

An apex predator affects prey population dynamics and defense tactics (such as camouflage).[77] The polar bear is the apex predator within its range.[78] Several animal species, particularly Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) and glaucous gulls (Larus hyperboreus), routinely scavenge polar bear kills.[79] The relationship between ringed seals and polar bears is so close that the abundance of ringed seals in some areas appears to regulate the density of polar bears, while polar bear predation in turn regulates density and reproductive success of ringed seals.[80] The evolutionary pressure of polar bear predation on seals probably accounts for some significant differences between Arctic and Antarctic seals. Compared to the Antarctic, where there is no major surface predator, Arctic seals use more breathing holes per individual, appear more restless when hauled out on the ice, and rarely defecate on the ice.[79] The fur of Arctic pups is white, presumably to provide camouflage from predators, whereas Antarctic pups all have dark fur.[79]

Killer whales are apex predators throughout their global distribution, and can have a profound effect on the behavior and population of prey species. Their diet is very broad and they can feed on many vertebrates in the ocean including

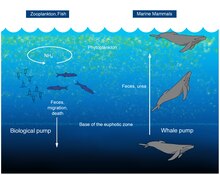

Whale pump

A 2010 study considered whales to be a positive influence to the productivity of ocean fisheries, in what has been termed a "whale pump". Whales carry nutrients such as nitrogen from the depths back to the surface. This functions as an upward biological pump, reversing an earlier presumption that whales accelerate the loss of nutrients to the bottom. This nitrogen input in the Gulf of Maine is more than the input of all rivers combined emptying into the gulf, some 25,000 short tons (23,000 t) each year.[89]

Upon death, whale carcasses fall to the deep ocean and provide a substantial habitat for marine life. Evidence of whale falls in present-day and fossil records shows that deep-sea whale falls support a rich assemblage of creatures, with a global diversity of 407 species, comparable to other

Interactions with humans

Threats

Due to the difficulty to survey populations, 38% of marine mammals are data deficient, especially around the Antarctic Polar Front. In particular, declines in the populations of completely marine mammals tend to go unnoticed 70% of the time.[32]

Exploitation

Marine mammals were hunted by coastal aboriginal humans historically for food and other resources. These subsistence hunts still occur in Canada, Greenland, Indonesia, Russia, the United States, and several nations in the Caribbean. The effects of these are only localized, as hunting efforts were on a relatively small scale.[31] Commercial hunting took this to a much greater scale and marine mammals were heavily exploited. This led to the extinction of the Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), sea mink (Neogale macrodon), Japanese sea lion (Zalophus japonicus), and the Caribbean monk seal (Neomonachus tropicalis).[31] Today, populations of species that were historically hunted, such as blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) and the North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica), are much lower than their pre-whaling levels.[93] Because whales generally have slow growth rates, are slow to reach sexual maturity, and have a low reproductive output, population recovery has been very slow.[46]

A number of whales are still subject to direct hunting, despite the 1986

The most profitable furs in the

Commercial sealing was historically just as important as the whaling industry. Exploited species included harp seals, hooded seals, Caspian seals, elephant seals, walruses and all species of fur seal.[99] The scale of seal harvesting decreased substantially after the 1960s,[100] after the Canadian government reduced the length of the hunting season and implemented measures to protect adult females.[101] Several species that were commercially exploited have rebounded in numbers; for example, Antarctic fur seals may be as numerous as they were prior to harvesting. The northern elephant seal was hunted to near extinction in the late 19th century, with only a small population remaining on Guadalupe Island. It has since recolonized much of its historic range, but has a population bottleneck.[99] Conversely, the Mediterranean monk seal was extirpated from much of its former range, which stretched from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea and northwest Africa, and remains only in the northeastern Mediterranean and some parts of northwest Africa.[102]

Polar bears can be hunted for sport in Canada with a special permit and accompaniment by a local guide. This can be an important source of income for small communities, as guided hunts bring in more income than selling the polar bear hide on markets. The United States, Russia, Norway, Greenland, and Canada allow subsistence hunting, and Canada distributes hunting permits to indigenous communities. The selling of these permits is a main source of income for many of these communities. Their hides can be used for subsistence purposes, kept as hunting trophies, or can be bought in markets.[103][104]

Ocean traffic and fisheries

Vessel strikes cause death for a number of marine mammals, especially whales.

The fishery industry not only threatens marine mammals through by-catch, but also through competition for food. Large-scale fisheries have led to the depletion of fish stocks that are important prey species for marine mammals. Pinnipeds have been especially affected by the direct loss of food supplies and in some cases the harvesting of fish has led to food shortages or dietary deficiencies,[111] starvation of young, and reduced recruitment into the population.[112] As the fish stocks have been depleted, the competition between marine mammals and fisheries has sometimes led to conflict. Large-scale culling of populations of marine mammals by commercial fishers has been initiated in a number of areas in order to protect fish stocks for human consumption.[113]

Shellfish aquaculture takes up space so in effect creates competition for space. However, there is little direct competition for aquaculture shellfish

Habitat loss and degradation

Two changes to the global

A study by evolutionary biologists at the University of Pittsburgh showed that the ancestors of many marine mammals stopped producing a certain enzyme that today protects against some neurotoxic chemicals called organophosphates,[120] including those found in the widely used pesticides chlorpyrifos and diazinon.[121] Marine mammals may be increasingly exposed to these compounds due to agricultural runoff reaching the world's oceans.

Protection

The

The Act was updated on 1 January 2016 with a clause banning "the import of fish from fisheries that cannot prove they meet US standards for protecting marine mammals".[124] The requirement to show that protection standards are met is hoped to compel countries exporting fish to the US to more strictly control their fisheries that no protected marine mammals are adversely affected by fishing.[124]

The 1979

The Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and contiguous Atlantic area (ACCOBAMS), founded in 1996, specifically protects cetaceans in the Mediterranean area, and "maintains a favorable status", a direct action against whaling.[128] There are 23 member states.[129]

The Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic and North Seas (ASCOBANS) was adopted alongside ACCOBAMS to establish a special protection area for Europe's increasingly threatened cetaceans.

The Agreement on the Conservation of Seals in the Wadden Sea, enforced in 1991, prohibits the killing or harassment of seals in the Wadden Sea, specifically targeting the harbor seal population.[132]

The 1973 Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears between Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway (Svalbard), the United States, and the Soviet Union outlawed the unregulated hunting of polar bears from aircraft and icebreakers, as well as protecting migration, feeding, and hibernation sites.[133]

Various

As food

For thousands of years, indigenous peoples of the Arctic have depended on whale meat & seal meat. The meat is harvested from legal, non-commercial hunts that occur twice a year in the spring and autumn. The meat is stored and eaten throughout the winter.[135] The skin and blubber (muktuk) taken from the bowhead, beluga, or narwhal is also valued, and is eaten raw or cooked. Whaling has also been practiced in the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic since about the time of the first Norse settlements on the islands. Around 1000 long-finned pilot whales are still killed annually, mainly during the summer.[136][137] Today, dolphin meat is consumed in a small number of countries worldwide, which include Japan[138][139] and Peru (where it is referred to as chancho marino, or "sea pork").[140] In some parts of the world, such as Taiji, Japan and the Faroe Islands, dolphins are traditionally considered food, and are killed in harpoon or drive hunts.[138]

There have been human health concerns associated with the consumption of dolphin meat in Japan after tests showed that dolphin meat contained high levels of methylmercury.[139][141] There are no known cases of mercury poisoning as a result of consuming dolphin meat, though the government continues to monitor people in areas where dolphin meat consumption is high. The Japanese government recommends that children and pregnant women avoid eating dolphin meat on a regular basis.[142] Similar concerns exist with the consumption of dolphin meat in the Faroe Islands, where prenatal exposure to methylmercury and PCBs primarily from the consumption of pilot whale meat has resulted in neuropsychological deficits amongst children.[141]

The Faroe Islands population was exposed to methylmercury largely from contaminated pilot whale meat, which contained very high levels of about 2 mg methylmercury/kg. However, the Faroe Islands populations also eat significant amounts of fish. The study of about 900 Faroese children showed that prenatal exposure to methylmercury resulted in neuropsychological deficits at 7 years of age

Ringed seals were once the main food staple for the

In captivity

Aquariums

- Cetaceans

Various species of dolphins are kept in captivity. These small cetaceans are more often than not kept in theme parks and dolphinariums, such as SeaWorld. Bottlenose dolphins are the most common species of dolphin kept in dolphinariums as they are relatively easy to train and have a long lifespan in captivity. Hundreds of bottlenose dolphins live in captivity across the world, though exact numbers are hard to determine.[146] The dolphin "smile" makes them popular attractions, as this is a welcoming facial expression in humans; however, the smile is due to a lack of facial muscles and subsequent lack of facial expressions.[147]

Organizations such as

- Pinnipeds

The large size and playfulness of pinnipeds make them popular attractions. Some exhibits have rocky backgrounds with artificial haul-out sites and a pool, while others have pens with small rocky, elevated shelters where the animals can dive into their pools. More elaborate exhibits contain deep pools that can be viewed underwater with rock-mimicking cement as haul-out areas. The most common pinniped species kept in captivity is the California sea lion as it is abundant and easy to train.

Some organizations, such as the Humane Society of the United States and World Animal Protection, object to keeping pinnipeds and other marine mammals in captivity. They state that the exhibits could not be large enough to house animals that have evolved to be migratory, and a pool could never replace the size and biodiversity of the ocean. They also oppose using sea lions for entertainment, claiming the tricks performed are "exaggerated variations of their natural behaviors" and distract the audience from the animal's unnatural environment.[155]

- Sea otter

Sea otters can do well in captivity, and are featured in over 40 public aquariums and zoos.[64] The Seattle Aquarium became the first institution to raise sea otters from conception to adulthood with the birth of Tichuk in 1979, followed by three more pups in the early 1980s.[156] In 2007, a YouTube video of two cute sea otters holding paws drew 1.5 million viewers in two weeks, and had over 20 million views as of January 2015[update].[157][158] Filmed five years previously at the Vancouver Aquarium, it was YouTube's most popular animal video at the time, although it has since been surpassed.[159] Otters are often viewed as having a "happy family life", but this is an anthropomorphism.[160]

- Sirenians

The oldest manatee in captivity was

Military

Bottlenose dolphins and California sea lions are used in the United States Navy Marine Mammal Program (NMMP) to detect mines, protect ships from enemy soldiers, and recover objects. The Navy has never trained attack dolphins, as they would not be able to discern allied soldiers from enemy soldiers. There were five marine mammal teams, each purposed for one of the three tasks: MK4 (dolphins), MK5 (sea lions), MK6 (dolphins and sea lions), MK7 (dolphins), and MK8 (dolphins); MK is short for mark. The dolphin teams were trained to detect and mark mines either attached to the seafloor or floating in the water column, because dolphins can use their echolocative abilities to detect mines. The sea lion team retrieved test equipment such as fake mines or bombs dropped from planes usually out of reach of divers who would have to make multiple dives. MK6 protects harbors and ships from enemy divers, and was operational in the Gulf War and Vietnam War. The dolphins would swim up behind enemy divers and attach a buoy to their air tank, so that they would float to the surface and alert nearby Navy personnel. Sea lions would hand-cuff the enemy, and try to outmaneuver their counter-attacks.[170][self-published source?][171]

The use of marine mammals by the Navy, even in accordance with the Navy's policy, continues to meet opposition. The Navy's policy says that only positive reinforcement is to be used while training the military dolphins, and that they be cared for in accordance with accepted standards in animal care. The inevitable stresses involved in training are topics of controversy, as their treatment is unlike the animals' natural lifestyle, especially towards their confined spaces when not training. There is also controversy over the use of

See also

References

- OCLC 30643250.

- ^ a b c Perrin, William F.; Baker, C. Scott; Berta, Annalisa; Boness, Daryl J.; Brownell Jr., Robert L.; Domning, Daryl P.; Fordyce, R. Ewan; Srembaa, Angie; Jefferson, Thomas A.; Kinze, Carl; Mead, James G.; Oliveira, Larissa R.; Rice, Dale W.; Rosel, Patricia E.; Wang, John Y.; Yamada, Tadasu, eds. (2014). "The Society for Marine Mammalogy's Taxonomy Committee List of Species and subspecies" (PDF). Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ISBN 9780763783440.

- ^ PMID 21625431.

- PMID 21808012.

- ^ OCLC 326418543.

- PMID 17516441.

- ^ JSTOR 4523580.

- ISBN 978-0-07-302819-4.

- S2CID 34683201.

- PMID 8015431.

- PMID 18590827.

- S2CID 45056197.

- PMID 9159933.

- PMID 19774069.

- S2CID 22005691.

- ^ OCLC 850909221.

- S2CID 59466434.

- S2CID 4371413.

- ^ PMID 16815048.

- OCLC 316226747.

- OCLC 25747993.

- JSTOR 3503828.

- ^ Kurtén, B (1964). "The evolution of the polar bear, Ursus maritimus Phipps". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 108: 1–30.

- ^ PMID 20194737.

- S2CID 86172292.

- S2CID 4420048.

- S2CID 91116726.

- PMID 21625431.

- ^ OCLC 42467530.

- ^ S2CID 45416687.

- ^ OCLC 19511610.

- OCLC 51242162.

- OCLC 51040880.

- OCLC 30436543.

- OCLC 1504461.

- ISBN 978-0-472-10100-9.

- ISBN 978-0-521-23274-6.

- ^ a b Perrin 2009, p. 360.

- ^ Lee, Jane J. (2015). "A Gray Whale Breaks The Record For Longest Mammal Migration". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- .

- ^ Pfeiffer, Carl J. (1997). "Renal cellular and tissue specializations in the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas)" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 23 (2): 75–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ISSN 0484-9019.

- S2CID 36151144.

- ^ OCLC 42309843.

- ^ OCLC 840278009.

- PMID 17516434.

- PMID 17516440.

- OCLC 24110680.

- ^ a b Perrin 2009, pp. 570–572.

- ^ U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service. "Coastal Stock(s) of Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin: Status Review and Management Proceedings and Recommendations from a Workshop held in Beaufort, North Carolina, 13 September 1993 – 14 September 1993" (PDF). pp. 56–57.

- ^ Gregory K. Silber, Dagmar Fertl (1995) – Intentional beaching by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Colorado River Delta, Mexico.

- OCLC 905649783.

- PMID 26393325.

- PMID 25942546.

- JSTOR 27859477.

- PMID 21147977.

- ^ Perrin 2009, pp. 806–813.

- ^ PBS.

- ^ Nickerson, p. 21

- OCLC 13760343.

- ^ "Sea otter". BBC. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ OCLC 46393741.

- .

- OCLC 48048972.

- PBS Nature. 17 February 2008. Archived from the originalon 16 June 2008.

- ^ Amstrup, Steven C.; Marcot, Bruce G.; Douglas, David C. (2007). Forecasting the range-wide status of polar bears at selected times in the 21st Century (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ OCLC 38862448.

- OCLC 488971350.

- S2CID 31644963.

- OCLC 773872519.

- OCLC 27492815.

- ^ Allen, Aarin Conrad; Keith, Edward O. (2015). "Using the West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus) as a Mechanism for Invasive Aquatic Plant Management in Florida". Journal of Aquatic Plant Management. 53: 95–104.

- S2CID 8925215.

- ^ "Aquatic Species at Risk – Species Profile – Sea Otter". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ISSN 0706-652X.

- ^ PMID 27755745.

- ^ OCLC 757032303.

- ^ Amstrup, Steven C.; Marcot, Bruce G.; Douglas, David C. (2007). Forecasting the range-wide status of polar bears at selected times in the 21st Century (PDF). Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ Barre, Lynne M.; Norberg, J. B.; Wiles, Gary J. (2005). Conservation Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) (PDF). Seattle: National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Northwest Regional Office. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-26.

- doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00822.x. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- .

- .

- OCLC 46973039.

- PMID 14526101.

- .

- PMID 19451116.

- ^ PMID 20949007.

- doi:10.1890/130220. Archived from the originalon 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ Smith, Craig R.; Baco, Amy R. (2003). "Ecology of Whale Falls at the Deep-Sea Floor" (PDF). Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. 41: 311–354.

- ^ S2CID 35737511.

- ^ "History of Whaling". The Húsavík Whale Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-06-21. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ "Modern Whaling". The Húsavík Whale Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- S2CID 83971988.

- ^ Harrison, John (2008). "Fur trade". Northwest Power & Conservation Council. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- OCLC 49225731.

- ^ OCLC 19511610.

- ^ Perrin 2009, pp. 585–588.

- OCLC 613421445.

- ^ Johnson, W. M.; Karamanlidis, A. A.; Dendrinos, P.; de Larrinoa, P. F.; Gazo, M.; González, L. M.; Güçlüsoy, H.; Pires, R.; Schnellmann, M. "Monk Seal Fact Files". monachus-guardian.org. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- .

- ^ "Overharvest". Polar Bears International. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Perrin, W. F. (1994) "Status of species" in Randall R. Reeves and Stephen Leatherwood (eds.) Dolphins, porpoises, and whales: 1994–1998 action plan for the conservation. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

- S2CID 32946729.

- ^ JSTOR 1383601.

- ^ OCLC 228169018.

- doi:10.1890/ES13-00004.1.

- .

- doi:10.1139/z00-060.

- .

- .

- JSTOR 1383602.

- PMID 9894350.

- .

- ISBN 9781118666470. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (9 August 2018). "Marine Mammals Have Lost a Gene That Now They May Desperately Need". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- PMID 30093596.

- OCLC 502874368.

- ^ a b c Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (PDF) (act). 2007. pp. 1–113. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b "A new law will try to save the planet's whales and dolphins through America's seafood purchasing power". Quartz. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- ^ "Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals" (PDF). 1979. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "CMS". Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Agreements". Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-25085-7.

- ^ "List of Contracting Parties and Signatories" (PDF). ACCOBAMS. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Catch Limits and Catches Taken". International Whaling Commission. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (PDF). International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Washington, D. C. 1946. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-92-893-0198-5.

- ^ "Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears". Oslo, Norway: IUCN/ Polar Bear Specialist Group. 1973. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "Marine Conservation Organizations". MarineBio. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Native Alaskans say oil drilling threatens way of life". BBC News. July 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Nguyen, Vi (26 November 2010). "Warning over contaminated whale meat as Faroe Islands' killing continues". The Ecologist. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Lee, Jane J. (September 2014). "Faroe Island Whaling, a 1,000-Year Tradition, Comes Under Renewed Fire". National Geographic. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b Matsutani, Minoru (September 23, 2009). "Details on how Japan's dolphin catches work". Japan Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Harnell, Boyd (2007). "Taiji officials: Dolphin meat 'toxic waste'". The Japan Times. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Hall, Kevin G. (2003). "Dolphin meat widely available in Peruvian stores: Despite protected status, 'sea pork' is popular fare". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 18 June 2016. [permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (2008). "Guidance for identifying populations at risk from mercury exposure" (PDF). p. 36. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. "平成15年6月3日に公表した「水銀を含有する魚介類等の 摂食に関する注意事項」について". Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (in Japanese).

- ^ "Eskimo Art, Inuit Art, Canadian Native Artwork, Canadian Aboriginal Artwork". Inuitarteskimoart.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ]

- ^ "5 Forslag til tiltak" (in Norwegian). Government of Norway. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Rose, Naomi; Parsons, E. C. M.; Farinato, Richard. The Case Against Marine Mammals in Captivity (PDF) (4th ed.). Humane Society of the United States. pp. 13, 42, 43, 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- OCLC 122974162.

- ^ Rose, N. A. (2011). "Killer Controversy: Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity" (PDF). Humane Society International and the Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Whale Attack Renews Captive Animal Debate". CBS News. March 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- OCLC 51818774.

- doi:10.1002/jtr.599.

- ^ OCLC 42213993.

- OCLC 51087217.

- ^ Sigvaldadóttir, Sigurrós Björg (2012). "Seals as Humans—Ideas of Anthropomorphism and Disneyfication" (PDF). Selasetur Working Paper (107). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-15.

- ^ "The Case Against Marine Mammals in Captivity" (PDF). Humane Society of the United States and World Animal Protection. pp. 3, 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Seattle Aquarium's Youngest Sea Otter Lootas Becomes a Mom". Business Wire. April 19, 2000. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- ^ cynthiaholmes (19 March 2007). "Otters holding hands". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- OCLC 656846644.

- ^ "Vancouver sea otters a hit on YouTube". CBC News. 3 April 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- OCLC 137241436.

- ^ Aronson, Claire. "Guinness World Records names Snooty of Bradenton as 'Oldest Manatee in Captivity'". bradenton.com. Bradenton Herald. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Caldwell, Alicia (October 2001). "He's a captive of affection". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Pitman, Craig (July 2008). "A manatee milestone: Snooty turning 60". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Meller, Katie (2017). "Snooty the famous manatee dies in 'heartbreaking accident' days after his 69th birthday". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ Blaszkiewitz, B. (1995). "Die Seekuhanlage im Tierpark Berlin-Friedrichsfelde". Zoologischer Garten (in German). 65: 175–181.

- ^ Mühling, P. (1985). "Zum ersten Mal: Drei Seekuhgeburten in einem Zoo. Erfolgreiche Haltung und Zucht von Rundschwanz-Seekühen (Trichechus manatus)". Tiergarten Aktuell (Nuremberg) (in German). 1 (1): 8–16.

- ^ "Extraordinary Animals: Manatees". Zooparc de Beauval. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- OCLC 934043451.

- ^ "Manatees move into world's largest freshwater aquarium at River Safari". The Straits Times. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ ]

- ^ OCLC 741119653.

Further reading

- Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J.G.M.; Kovacs, Kit M., eds. (2018). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Third ed.). ISBN 9780128043271.

- Berta, Annalisa. Sea Mammals: The Past and Present Lives of Our Oceans’ Cornerstone Species (Princeton University Press, 2023) ISBN 978-0-691-23664-3. online book review

External links

- The Marine Mammal Center A conservation group that focuses on marine mammals

- The Society for Marine Mammalogy The largest organization of marine mammalogists in the world.

- The MarineBio Conservation Society An online education site on marine life

- National Oceanographic and Atmosphere Administration An agency that focuses on the conditions of the ocean and the climate

- Introduction to the Desmostylia Museum of Paleontology, University of California – extinct group of marine mammals