East Indies theatre of the French Revolutionary Wars

| East Indies theatre of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

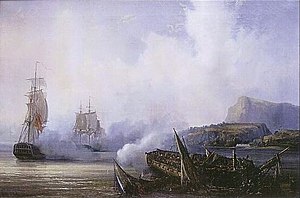

Combat de la Preneuse, Auguste Mayer | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Ignacio Álava | ||||||

The East Indies theatre of the French Revolutionary Wars was a series of campaigns related to the major European conflict known as the

Protection of British interests in the region fell primarily to the

At the declaration of war on Britain by the newly formed

In 1796 British control of the region was challenged by a large and powerful French frigate squadron sent to the Indian Ocean under

Background

On 1 February 1793, amid mounting tensions following the

Britain, through the EIC, controlled large stretches of the Indian coast, including the three significant ports of

France controlled a number of trading harbours along the Indian coast including

The

The

The East Indies were very important to the British war effort due to their pivotal position in maintaining British revenue through trade. The EIC controlled the shipment of large quantities of valuable commodities from India, China and other Asian markets to Europe with their fleet of large and well-armed merchant ships, known as

Campaigns

News of the French declaration of war arrived by ship in Calcutta, having traveled from George Baldwin, British ambassador in Alexandria, on 1 June 1793.[25] Cornwallis immediately sailed to Pondicherry, instituting a blockade and seizing an ammunition supply ship entering the port.[26] Plans to eliminate the French presence in India had already been drawn up. The British and EIC forces, commanded on land by Colonel John Braithwaite, moved rapidly, seizing Chandernagore, Karaikal, Yanam and Mahé without resistance. Pondicherry proved stronger, and Braithwaite was forced to besiege the city for 22 days until the French commander, Colonel Prosper de Clermont, agreed to surrender.[27] Cornwallis's blockade was augmented by several large East Indiamen, proving sufficient as a deterrent to drive off the French frigate Cybèle and accompanying storeships which sought to resupply the garrison on 14 August.[28]

With the French firmly driven from India, Cornwallis returned to European waters with Minerva. Protection of EIC shipping from French forces was left to a small number of light EIC warships.[28][Note A] The trade route through the Sunda Strait proved particularly vulnerable; on 27 September 1793 a squadron of large privateers captured the East Indiaman Princess Royal. In January 1794 a well armed squadron of East Indiamen under Commodore Charles Mitchell were sent to patrol the Sunda Strait by the EIC.[24] During the ensuing Sunda Strait campaign, privateers attacked the East Indiaman Pigot on 17 January before Mitchell defeated the largest privateers, Vengeur and Résolu, on 22 January and fought an inconclusive engagement with Prudente and Cybèle under Captain Jean-Marie Renaud on 24 January. Renaud subsequently captured the Pigot, while she was under repairs at Fort Marlborough. In late February both French and EIC squadrons returned to the Indian Ocean. The Dutch frigate Amazone subsequently captured two French corvettes at Sourabaya.[29]

In the early spring of 1794, during a major campaign in the Atlantic, a British force led by Captain Peter Rainier in the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Suffolk, also including HMS Swift, HMS Orpheus, HMS Centurion and HMS Resistance, was sent to the Indian Ocean.[30] This force diverged en route, with Orpheus, Resistance and Centurion cruising off Île de France in May.[31] On 5 May this force encountered the captured Princess Royal, now armed as a warship and renamed Duguay-Trouin, and the brig Vulcain. Duguay-Trouin sailed poorly and was intercepted and captured by Orpheus after a short battle.[32] The blockade of Île de France was maintained during the year and on 22 October Renaud attempted to eliminate it, attacking Centurion and Diomede off Île Ronde.[11] The ensuing battle was hard-fought, with a particularly ferocious duel between Centurion and Cybèle, but ultimately the British squadron was forced to withdraw to India.[33]

Batavian campaigns

"What was a feather in the hands of the Dutch will become a sword in the hands of France."

Rainier decided not to renew the blockade of Île de France in 1794, concerned by false rumours that a French battle squadron was sailing to the East Indies.[35] In July 1795 news arrived in India which significantly changed the strategic situation: during the winter of 1794–1795 the French Army had overrun the Dutch Republic, reforming the country into an allied client state named the Batavian Republic.[36] Control of the Dutch colonies, whose loyalty was uncertain, became Rainier's main priority due principally to their strategic positions along intercontinental trade routes, and he immediately organised operations to seize them.[37] The largest force, with Rainier in personal command, descended on Trincomalee, while a smaller force under Captain Edward Pakenham in Resistance sailed for Malacca.[38]

Rainier hoped that the Dutch commanders would peacefully transfer control of their colonies to the British after provision of the

Batavian control of the

British consolidation

Elphinstone's arrival at the Cape officially placed him in overall command of the East Indies squadron, but the great distances involved meant that immediate operational control remained with Rainier.[45] In July 1795 Prudente and Cybèle sailed from Île de France and attacked shipping in the Sunda Strait, seizing a number of merchant ships. When reports of this attack reached Rainier he took most of his squadron eastwards to the Dutch East Indies, leaving only Gardner's squadron to watch Colombo.[46] Elphinstone assumed command of the Western Indian Ocean, sending HMS Stately and HMS Victorious to restore the blockade of Île de France and taking HMS Monarch, HMS Arrogant and sloops HMS Echo and HMS Rattlesnake to Madras, where he arrived on 15 January 1796.[47] In France, an operation to reinforce the Indian Ocean with a squadron of razee frigates or ships of the line under Contre-amiral Kerguelen had been planned in 1794 but repeatedly delayed due to lack of suitable ships and commitments elsewhere. In the summer of 1795 these plans were abandoned completely following losses at the Battle of Groix and French intervention in the East Indies was not attempted until the spring of 1796.[48]

The renewed blockade of Île de France was lifted in December 1795, and Elphinstone deployed most of his forces in the continued blockade of Colombo.

Alarmed at the distance Elphinstone had been forced to travel to defend the Cape, the Admiralty separated command of the Cape and the East Indies in Spring 1796.

Sercey's squadron

Until 1796 there had been no reaction from the French Convention to the operations in the East Indies, and they were eventually inspired to reinforce the region not by British actions but by French ones. In 1795 orders had arrived at Île de France formally abolishing slavery. The Colonial Assembly on the island, whose wealth relied on slave labour, simply ignored the order. The matter was taken up by the

Sercey's voyage started badly, losing Cocarde to an accident on the French coast and Bonne Citoyenne and Mutine to British frigate patrols in the Bay of Biscay. Once out of European waters, however, his passage was unchallenged, watering at La Palma, where Vertu joined the squadron, and capturing the whaler Lord Hawkesbury in the South Atlantic. Baco and Burnel proved a bigger problem: at one stage the squabbling pair attempted to kill one another and had to be pulled apart by Sercey.[57] The squadron took a Portuguese Indiaman off Cape Agulhas on 24 May and the following day encountered and unsuccessfully pursued HMS Sphynx. On 3 June Sercey seized a British Indiaman and his squadron arrived at Île de France unopposed on 18 June, the blockade squadron having departed the coast a few days earlier.[58] The Colonial Assembly had been forewarned of the arrival of the government agents, possibly by Sercey, and they were met with armed troops. The agents demanded Magallon attack the colonial troops, but he refused to do so, and Baco and Burnel were forced onto the corvette Moineau. Moineau was instructed to take the agents to Manila, but once at sea they overruled the captain and ordered him to take them back to France.[59]

Sercey refitted his squadron at Île de France, dividing it into two forces. The largest, comprising Forte, Prudente, Seine, Régénérée, Vertu and Cybèle was to sail eastwards under his command. The second, comprising the recently arrived

After attacking

French dispersal

Sercey's campaign had ended in failure, with little disruption to British trade or naval operations in the East Indies. The East India Company had however taken more serious losses from the depredations of privateers. Most active was

No French reinforcements reached the East Indies in 1797. A complex strategy had been developed to land an army in

Other British ships were operating in the East Indies: in July 1797, Resistance and a force of EIC troops captured

Maintenance of the blockade of Île de France was the responsibility of the substantial British squadron at the Cape Colony, which had suffered severely from unrest inspired by the

Red Sea and Mysore

In July 1798

British attention elsewhere in the theatre was focused on Southern India. In January 1798, a French privateer brought envoys from Mysore to Île de France with a request for support. Malartic supplied 86 volunteers, which were sent to India on Preneuse under Captain

British dominance

During the summer of 1798, Forte and Prudente conducted a commerce raiding operation under Captain Ravanel in the Bay of Bengal and the Bali Strait which achieved moderate success but also saw the first of a number of mutinies among Sercey's crews.

Sercey's fury at the seizure of his strongest frigates was compounded by the condition of Preneuse, which arrived at Batavia in a state of mutiny. Lhermitte had executed five crew on the journey and Sercey immediately sent the ship out again on a cruise off Borneo in an effort to contain the disaffection.[89] With his forces unexpectedly reduced, Sercey then sent his remaining ships to Manila for operations with the Spanish, but the condition of the Spanish ships was so poor that no operations could be undertaken in 1798.[89] An attack on the China Fleet was eventually attempted in January 1799, but on arrival at Macau the combined Spanish squadron refused to engage the powerful British escort and the entire force withdrew, pursued by Captain William Hargood in HMS Intrepid.[90]

Disappointed by the failure off Macau and weakened by losses to his squadron, Sercey withdrew to Île de France in the spring of 1799. There he sent Preneuse on a raiding cruise in the Mozambique Channel. On 20 September, Lhermitte fought a brief and inconclusive night engagement with a small squadron of Royal Navy ships in

As the French naval presence in the Indian Ocean declined, the commerce raiding role was taken up by privateers. These fast vessels operated with considerable success against British merchant shipping, and protecting convoys from their depredations consumed a considerable proportion of Rainier's naval strength: gradually however they were intercepted and captured, including Adele in May 1800 and L'Uni in August 1800.[96] Among the more notorious privateers was Iphigenie, which seized a packet ship, Pearl, in the Persian Gulf in October 1799. Pursued by the sloop HMS Trincomalee, the two fought a fierce engagement on 12 October at which both ships were destroyed and more than 200 men killed.[97] Most dangerous among the privateersmen was Robert Surcouf, who sailed in Clarissa and then Confiance. In the latter he fought a significant battle off the Hooghly River on 9 October 1800 with the East Indiaman Kent.[98] Eventually subdued by a boarding action, Kent lost 14 killed, including Captain Robert Rivington, and 44 wounded; Surcouf's men suffered 14 casualties.[99][100] The privateer conflict continued to the end of the war, the large privateers Grand Hirondelle and Gloire remaining at sea into 1801 before being captured, and Courier and Surcouf's Confiance evading interception entirely.[96]

Final Actions

Rainier's main priorities remained the protection of trade, but his command came under increasing interference from London, in particular the Secretary of State for War Henry Dundas. Dundas was insistent throughout 1799 and 1800 that the priority for Rainier should be the invasion and capture of Java, thus eliminating the Dutch East Indies entirely. Contradictory orders came from Lord Mornington, who was instructing Rainier to plan an invasion of Île de France, while Rainier himself wished to resurrect the abandoned operation against Manila.[101] So confused was the command structure that in September 1800 Rainier threatened to resign,[102] but in October 1800 a renewed threat from Egypt redirected the focus of his squadron to the Red Sea and only a handful of minor operations against Dutch posts on Java were carried out by a small force under Captain Henry Lidgbird Ball, capturing a few merchant ships but losing more than 200 men to disease in the process.[103] At the Cape of Good Hope, a gale on 5 December 1799 caused severe damage to shipping in Table Bay: among the wrecks were HMS Sceptre with 290 crew, the Danish ship of the line Oldenburg and several large American merchant ships.[104]

The Red Sea campaign of 1801 was intended to complement the British invasion of French-held Egypt from the Mediterranean, which went ahead in March 1801. Initial operations were trusted to Blankett at

The French Navy played little part in opposing the British campaign in Egypt, but a frigate was sent to the Indian Ocean to interfere with the supply lines to the Red Sea. This ship, Chiffonne was based at Mahé in the Seychelles.[108] The voyage had been eventful, Chiffonne seizing a Brazilian frigate Andhorina in the Atlantic and the East Indiaman Bellona, as well as conveying 32 political prisoners sentenced to exile in the Indian Ocean. At the Battle of Mahé on 19 August however, Chiffonne was discovered at anchor by Sybille and captured.[109] The final operations in the Indian Ocean saw British forces consolidate further, landing troops at the Portuguese colonies in the region to prevent the enforcement of the terms of the Treaty of Badajoz, under which Portugal agreed to exclude British shipping from its ports, while the EIC attacked and captured the Dutch island of Ternate.[110]

Aftermath

The

Notes

- Admiralty that he was returning to Britain as he had received "no Intelligence of Importance". Apparently his own crew were unaware of his intentions, and his departure caused consternation among the British authorities in India.[117] Cornwallis's orders, issued in 1791, granted him discretion over when to retire from the East Indies and protected him from censure,[118] but it is clear that the Admiralty expected him to remain in Indian waters: Rainier's orders explicitly placed him subordinate to Cornwallis, who was already on his return journey when they were issued and actually arrived at Spithead while Rainier was still at anchor there.[119]

Citations

- ^ Chandler, p. 373.

- ^ Rodger, p. 275.

- ^ Rodger, p. 357.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 118.

- ^ a b Chandler, p. 442.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 12.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 13.

- ^ Mostert, p. 98.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 15.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 19.

- ^ a b Woodman, p. 49.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 72.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 30.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 34.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 35.

- ^ Rodger, p. 364.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 40.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 36.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 37.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 44.

- ^ Gardiner, Victory of Seapower, p. 102.

- ^ Gardiner, Fleet Battle and Blockade, p. 72.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 60.

- ^ a b c James, Vol. 1, p. 196.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 119.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 61.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 120.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 62.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 198.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 68.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 203.

- ^ Clowes, p. 484.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 212.

- ^ Mostert, p. 161.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 77.

- ^ Chandler, p. 44.

- ^ Rodger, p. 435.

- ^ a b James, Vol. 1, p. 302.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 79.

- ^ Clowes, p. 282.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 304.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 80.

- ^ Clowes, p. 281.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 373.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 82.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 83.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 84.

- ^ a b James, Vol. 1, p. 347.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 371.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 86.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 372.

- ^ Clowes, p. 294.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 95.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 89.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 374.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 97.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 98.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 348.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 100.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 349.

- ^ Clowes, p. 503.

- ^ James, Vol. 1, p. 353.

- ^ Woodman, p. 114.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 106.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 108.

- ^ Clowes, p. 297.

- ^ James, Vol. 2, p. 3.

- ^ Henderson, p. 104.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 112.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 117.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 119.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 137.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 136.

- ^ Grocott, p. 59.

- ^ Mostert, p. 213.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 120.

- ^ James, Vol. 2, p. 219.

- ^ Clowes, p. 511.

- ^ Chandler, p. 350.

- ^ Chandler, p. 315.

- ^ Rodger, p. 460.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 149.

- ^ Clowes, p. 405.

- ^ Clowes, p. 406.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 121.

- ^ Grocott, p. 57.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 123.

- ^ Clowes, p. 520.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 124.

- ^ Gardiner, Nelson Against Napoleon, p. 160.

- ^ James, Vol. 2, p. 346.

- ^ Clowes, p. 524.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 130.

- ^ Grocott, p. 89.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 131.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 159.

- ^ James, Vol. 2, p. 355.

- ^ Woodman, p. 128.

- ^ James, Vol. 3, p. 53.

- ^ Grocott, p. 96.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 158.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 165.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 171.

- ^ Grocott, p. 87.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 174.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 179.

- ^ Gardiner, Nelson Against Napoleon, p. 163.

- ^ Woodman, p. 151.

- ^ Gardiner, Nelson Against Napoleon, p. 168.

- ^ James, Vol. 3, p. 160.

- ^ Chandler, p. 10.

- ^ a b Parkinson, p. 181.

- ^ James, Vol. 3, p. 162.

- ^ Woodman, p. 172.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Rodger, p. 523.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 63.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 70.

- ^ Parkinson, p. 69.

References

- ISBN 1-84022-203-4.

- ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1996]. Fleet Battle and Blockade. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-363-X.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed; Woodman, Richard (2001) [1996]. Nelson against Napoleon: from the Nile to Copenhagen, 1798–1801. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4.)

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- Grocott, Terence (2002) [1997]. Shipwrecks of the Revolutionary & Napoleonic Era. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-164-5.

- Henderson, James, CBE (1994) [1970]. The Frigates. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-432-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 0-85177-905-0.

- ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- ISBN 0-85177-907-7.

- Mostert, Noel (2007). The Line upon a Wind: The Greatest War Fought at Sea Under Sail 1793 – 1815. London: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-7126-0927-2.

- Parkinson, C. Northcote (1954). War in the Eastern Seas, 1793 – 1815. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- ISBN 0-7139-9411-8.

- ISBN 1-84119-183-3.