Algeciras campaign

| Algeciras campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Second Coalition | |||||||

The battle of Algeciras, Alfred Morel-Fatio | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

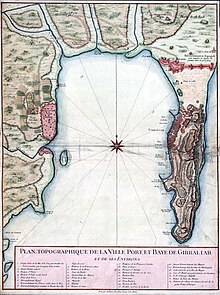

The Algeciras campaign (sometimes known as the Battle or Battles of Algeciras) was an attempt by a French naval squadron from

In the aftermath of the first battle, both sides set about making urgent repairs and calling up reinforcements. On 9 July a fleet of five Spanish and one French ship of the line and several frigates arrived from Cadiz to safely escort Linois's squadron to Cadiz, and the British at Gibraltar redoubled their efforts to restore their squadron to fighting service. In the evening of 12 July the French and Spanish fleet sailed from Algeciras, and the British force followed them, catching the trailing ships in the

Ultimately the French and Spanish fleets were successful in their aim of uniting at Cadiz, albeit after heavy losses, but they were still under blockade and in no position to realise either the Egyptian or Portuguese plans. The two battles, "generally regarded as a single linked battle",[1] proved decisive in cementing British control of the Mediterranean Sea and condemning the French army in Egypt to defeat, totally unsupported by reinforcements from the French Navy.

Background

On 1 August 1798, a British fleet surprised and almost completely destroyed the French Mediterranean Fleet at the

In January 1801, in an attempt to increase the size of the French Mediterranean Fleet and to reinforce the beleaguered Egyptian garrison,

The presence of this force at Toulon enabled the French to plan a secondary operation using Ganteaume's new arrivals. A deal had been brokered earlier in the year between Bonaparte and

Linois's voyage

Linois sailed from Toulon on 13 June 1801 with three ships of the line and one frigate carrying 1,560 soldiers under Brigadier-General

Linois passed Gibraltar on 3 July and during the night discovered the 14-gun

Off Cadiz, the squadron under Saumarez was notified of Linois's arrival by Lieutenant Janvarin at 02:00 on 5 July and immediately turned back towards Gibraltar,

First Battle of Algeciras

At 07:00, Saumarez ordered his squadron to advance into the bay without delay and engage the French directly, the attack to be led by Captain

Saumarez ordered his squadron's boats to assist Hannibal and Pompée, both of which were trapped under heavy fire and unable to effectively respond.

Hannibal had been exposed to the combined French and Spanish fire for four hours, and had lost two masts and more than 140 men killed and wounded. In an effort to preserve the lives of his crew, Ferris ordered his men to shelter below decks, but at 14:00 fires broke out on the ship and Ferris, isolated by Saumarez's withdrawal, surrendered his ship.

The French victory had come at a heavy cost: more than 160 men were killed and 300 wounded and all three French ships had been severely damaged.

Interlude

Immediately following the battle, Linois used overland messengers to request the assistance of the Spanish fleet at Cadiz under Admiral

Linois also began a programme of refloating and making extensive repairs to his ships, including the captured Hannibal, which he renamed Annibal.

The departure of this combined squadron was observed by Captain Richard Goodwin Keats on HMS Superb, which after returning to Cadiz had retained station off the port with HMS Thames and HMS Pasley. Thames was inshore searching a seized American merchant ship, and witnessed the emergence of the squadron retreating before four ships of the line that approached the British frigate. Superb was sighted shortly afterwards and also retreated before a ship of the line and two frigates, as they repaired to the outer roads ready to sail with the land breeze the following morning.[42] As the fleet prepared to sail in the morning Keats immediately sent Pasley ahead to Gibraltar to warn Saumarez, the brig arriving at 15:00 closely followed by the British men of war sailing under a crowd of canvas and signalling the approach of the enemy as they arrived up. No sooner had they rounded Cabrita Point than the Spanish reinforcements were seen entering the bay (save for Saint Antoine, which had been unable to work out of the harbour and arrived the following day). Moreno's squadron anchored in the Bay of Gibraltar, out of reach of the British batteries on Gibraltar and waited there for Linois to complete his repairs, Saint Antoine joining the squadron on the morning of 10 July.[43] Keats brought his ships into Gibraltar, where efforts to repair the squadron were increased, with the knowledge that Moreno would soon be sailing to Cadiz with Linois squadron.[35] Saumarez, concerned by the size of the combined squadron, sent urgent messages to the Mediterranean Fleet under Lord Keith in the Eastern Mediterranean requesting support in the belief that Moreno would be delayed at least two weeks due to the condition of Linois's ships.[36] Saumarez was wrong: Moreno planned to convoy the battered squadron the short distance to Cadiz as soon as they were seaworthy.

Second battle of Algeciras

On the morning of 12 July the combined French and Spanish squadron put to sea, followed closely by the British squadron. Both sides took most of the day to assemble, hampered by light winds and damaged warships, but at 19:00 Moreno gave orders for his squadron to make all sail westwards towards the open ocean and Cadiz. Saumarez followed, but at 20:40, with night drawing in and the wind picking up, he instructed Keats to take Superb, the fastest ship in his squadron, ahead and engage the rearguard of Moreno's force.[7]

The wind soon freshened to a hard gale in the straits and the Superb went at 11.5 knots, leaving her compatriots some miles behind as she closed on the retreating enemy.[44] At 23:20, with lights concealed and making no signals, she ranged up alongside a Spanish three- decker -the Real Carlos, and discharged three broadsides into her before being met by return of fire. Some of the shot was high and passed through the rigging of the Real Carlos to hit a ship to her larboard – the Spanish three-decker San Hermenegildo. In the confusion she mistook the Real Carlos as her enemy, which resulted in a general cannonade throughout the enemy squadron. In about ten minutes the Real Carlos was observed to be on fire. The San Hermenegildo still believing the Real Carlos to be the enemy closed to send raking fire through her stern, but was caught in a violent gust that brought the two ships together so the fire spread to both ships, which subsequently blew up – the concussion being felt as far away as Cádiz – and were completely destroyed with horrendous loss of life. More than 1700 men perished.[45] At some stage during the night, the independently sailing Spanish frigate Perla sailed through the battle and was fatally damaged in the crossfire, sinking the next morning.[46]

Keats meanwhile had engaged and defeated Saint Antoine, forcing the wounded Commodore Julien le Ray to surrender following an action that had lasted just half an hour. Casualties on Saint Antoine were heavy, although Superb had just 15 men wounded. The rest of the British squadron, following up in the darkness, mistook Saint Antoine as being still active, and all fired on the ship as they passed, intending to catch the remainder of Moreno's squadron as it sailed northwest along the Spanish coastline.[47] At 04:00 the Formidable, now under the command of Captain Amable Troude, was seen to the north in Conil Bay near Cape Trafalgar and Saumarez sent Venerable to chase the French ship, Hood accompanied by Thames under Captain Aiskew Hollis. At 05:15, Venerable came within range and a close action soon followed, Hood ordering Hollis to bring his ship close to Troude's stern and open up a raking fire. Formidable had the better of the action however and at 06:45, with casualties mounting, Hood's mainmast collapsed over the side.[48] Note B

Taking advantage of the disability to the British ship, Troude pulled Formidable ahead in light winds, slowly rejoining the main squadron under Moreno, which was holding station off Cadiz harbour.[49] As Formidable moved away, the remaining masts on Venerable collapsed and the ship grounded off Sancti Petri. There was concern in the British squadron that Moreno might counterattack the disabled ship, but the arrival on the horizon of Audacious and Superb persuaded the Spanish admiral to withdraw into Cadiz.[45] Hood was able to refloat Venerable on 13 July and the ship was towed back to Gibraltar with the prize Saint Antoine. Saumarez left three ships to maintain the blockade at Cadiz, returning the situation off the port to that before the battle.[50]

Aftermath

In France the campaign was represented as a victory, as Linois' genuine achievements at Algeciras were followed by exaggerated reports of Troude's defence in Conil Bay in which the second battle was represented as a significant success against a more numerous British force. Troude had shown skill and bravery in the engagement, but his subsequent reputation was largely built on the strength of a report sent to Paris by Dumanoir le Pelley which was based on a letter written by Captain Troude. In the letter, he claimed that he had fought not only Venerable and Thames, but also Caesar and Spencer (misidentified in the report as Superb).[51] Troude stated that he had not only driven all of these ships off, but that he had also completely destroyed Venerable by driving the ship ashore. Troude was subsequently promoted and highly praised, holding a number of important active commands in the French Navy.[52] In Spain, the outcome of the campaign infuriated the Spanish government and contributed to the souring of the Franco-Spanish alliance. The Spanish demanded that the Spanish forces then stationed at Brest on the French Atlantic coast return to Spanish waters, and Spanish pressure on Portugal was relaxed. This weakening of the Franco-Spanish axis was a significant factor in the Treaty of Amiens in early 1802 that brought the French Revolutionary Wars to a close.[53]

Saumarez was lauded in Britain, the success of the second action mitigating the initial defeat. He was awarded the thanks of both

The severe losses inflicted on the Spanish fleet at Cadiz and the reinstatement of the blockade meant that the French plan to reinforce the army trapped in Egypt was a total failure, the garrison there surrendering in September after a hard-fought campaign against British and Ottoman forces.[56] It also emphasised British dominance at sea by this stage of the war, reiterating that no force could sail from a French or allied port without detection and interception by the Royal Navy, but still not dominant enough to conquer the bulk of Spanish America.[57]

Legacy

The campaign later played a prominent part in the novels Master and Commander by Patrick O'Brian and Touch and Go by C. Northcote Parkinson.[58][59]

Notes

- ^ Note A: Reports of French casualties in the first battle vary widely. James and Clowes quote French reports of 306 killed and 280 wounded in total and Spanish reports that the French suffered 500 wounded.[31][32] However in his breakdown of French casualties ship by ship, Musteen only records 161 killed and 324 wounded.[34]

Note B Keats's detailed account is recorded in; 'Narrative of the Services of His Majesty's Ship Superb, 74, on the night of 12 July 1801 and the two following days, by her then Captain, Sir Richard Goodwin Keats G.C.B &' -Longmans, London, 1838. Somerset Records Office, DD/CPL/30; reproduced in Hannah, P., 'A Treasure to the Service', Green Hill, Adelaide, 2021, ISBN 978-1-922629-73-9, appendix III

References

- ^ a b Mostert, p. 408

- ^ Gardiner, p. 58

- ^ Gardiner, p. 16

- ^ James, p. 87

- ^ Woodman, p. 158

- ^ James, p. 93

- ^ a b c Woodman, p. 161

- ^ a b Clowes, p. 459

- ^ a b James, p. 112

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24685. Retrieved 13 September 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ a b James, p. 123

- ^ a b Musteen, p. 33

- ^ Clowes, p. 458

- ^ James, p. 113

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5757. Retrieved 13 September 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Adkins, p. 92

- ^ Harvey, p. 58

- ^ Harvey, p. 59

- ^ Musteen, p. 32

- ^ Clowes, p. 460

- ^ James, p. 124

- ^ a b Mostert, p. 404

- ^ James, p. 115

- ^ Clowes, p. 461

- ^ James, p. 116

- ^ a b Clowes, p. 463

- ^ James, p. 117

- ^ Gardiner, p. 89

- ^ Mostert, p. 405

- ^ a b Clowes, p. 464

- ^ a b Clowes, p. 465

- ^ a b James, p. 119

- ^ Gardiner, p. 91

- ^ a b Musteen, p. 41

- ^ a b Mostert, p. 406

- ^ a b Musteen, p. 43

- ^ James, p. 125

- ^ James, p. 122

- ^ Musteen, p. 45

- ^ a b James, p. 126

- ^ Clowes, p. 466

- ^ Hannah, p. 66

- ^ Gardiner, p. 92

- ^ Hannah, p. 68

- ^ a b Gardiner, p. 93

- ^ James, p. 354

- ^ James, p. 128

- ^ Clowes, p. 468

- ^ James, p. 129

- ^ a b James, p. 130

- ^ James, p. 131

- ^ Clowes, p. 469

- ^ Rodger, p. 472

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 240.

- ^ Mostert, p. 409

- ^ Clowes, p. 470

- ISBN 0006499155

- ISBN 0417024606

Bibliography

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11916-8.

- ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1996]. Nelson Against Napoleon. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4.

- Hannah, P. (2021). A Treasure to the Service. ISBN 978-1922629739.

- Harvey, Robert (2000). Cochrane: The Life and Exploits of a Fighting Captain. Constable. ISBN 1-84119-162-0.

- ISBN 0-85177-907-7.

- Mostert, Noel (2007). The Line upon a Wind: The Greatest War Fought at Sea Under Sail 1793–1815. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-7126-0927-2.

- Musteen, Jason R. (2011). Nelson's Refuge: Gibraltar in the Age of Napoleon. Naval Investiture Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-545-5.

- ISBN 0-71399-411-8.

- ISBN 1-84119-183-3.

External links

Media related to Battle of Algeciras Bay at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Algeciras Bay at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Second Battle of Algeciras (1801) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Second Battle of Algeciras (1801) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Treaty of Florence |

French Revolution: Revolutionary campaigns Algeciras campaign |

Succeeded by Treaty of Amiens |