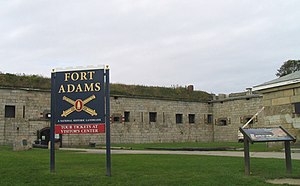

Fort Adams

| Fort Adams | |

|---|---|

| Newport, Rhode Island | |

Fort Adams on 31 August 2005 | |

| Type | Coastal artillery post |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | United States |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1798–1799; 1824–1857 |

| In use | 1799–1824; 1841–1953 |

| Materials | granite, shale and brick |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Captain John Henry Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Kendrick Pierce Brigadier General Robert Anderson Colonel Henry Jackson Hunt[1] |

Fort Adams | |

Interactive map showing the location of Fort Adams | |

| Nearest city | Joseph G. Totten (1824) |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000014 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 28, 1970[3] |

| Designated NHLD | December 8, 1976[2] |

Fort Adams is a former United States Army post in Newport, Rhode Island, that was established on July 4, 1799, as a First System coastal fortification, named for President John Adams, who was in office at the time. Its first commanding officer was Captain John Henry who was later instrumental in starting the War of 1812. The current Fort Adams was built between 1824 and 1857 under the Third System of coastal forts; it is part of Fort Adams State Park today.

History

The first Fort Adams was designed by

After the War of 1812, there was a thorough review of the fortification needs of the United States and it was decided to replace the older Fort Adams with a newer and much larger fort. This was part of what became known as the Third System of U.S. fortifications. The new fort was designed by

Construction of the new fort began in 1824 under

The new Fort Adams was first garrisoned in August 1841, functioning as an active U.S. Army post until 1950. During this time the fort was active in five major wars – the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), American Civil War (1861–1865), Spanish–American War (1898), World War I (1917–1918), and World War II (1941–1945) — but never fired a shot in anger.

At the start of the Mexican–American War in 1846, the post was commanded by Benjamin Kendrick Pierce, the brother of President Franklin Pierce. The fort's redoubt, about 1⁄4 mile (0.4 km) south of the main fort, was built during this war.[11][12][7]

From 1848 to 1853, Fort Adams was commanded by Colonel William Gates, a long-serving veteran of both the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War. The fort's garrison was ordered to California and many of the soldiers lost their lives when the steamer SS San Francisco was wrecked in a North Atlantic storm on December 24, 1853.

A report of 1854 stated that Fort Adams was armed with 100 32-pounder seacoast guns, 57 24-pounder seacoast guns, and 43 24-pounder flank howitzers. All of these weapons were smoothbore cannon. The flank howitzers were short-barreled guns deployed in casemates in the tenaille and redoubt to protect the fort against a landward assault.[13]

From 1859 to 1863 the fort was in the

Civil War

The

Among the midshipmen assigned to the Naval Academy while it was at Fort Adams was

In 1862 Fort Adams became the headquarters and recruit depot for the U.S. Army's 15th Infantry Regiment. This regiment, along with several others, was reorganized into a regiment of three eight-company battalions, with the 3rd Battalion formed at Fort Adams in March 1864.

From August to October 1863, Fort Adams was commanded by Brigadier General Robert Anderson, who had commanded Fort Sumter when it was attacked by Confederate forces in April 1861, beginning the American Civil War.

1870s upgrade

As part of a major upgrade to U.S. seacoast defenses, Fort Adams' armament was modernized in the 1870s with eleven 15-inch (381 mm) Rodman guns, thirteen 10-inch (254 mm) Rodman guns, and four 6.4-inch (163 mm) (100-pounder) Parrott rifles. Three new emplacements were built for the 15-inch (381 mm) guns; the remainder replaced older weapons in the fort, of which all but 20 32-pounders were removed by 1873. For mobile defense, four 4.5-inch (114 mm) siege rifles, four 3-inch (76.2 mm) Ordnance rifles, and four 10-inch (254 mm) mortars were provided. In 1894, four 8-inch (203 mm) converted rifles were added in a new battery south of the fort.[13]

Twentieth century

Endicott period

As time went by, the fort's armament was upgraded to keep up with technological innovations. Major kinds of ordnance used at the fort included muzzle-loading cannon in the 19th century, rifled

The Endicott and Taft-period batteries at Fort Adams were:[11][15]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greene-Edgerton | 16 | 12-inch (305 mm) coast defense mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1898–1942 |

| Reilly | 2 | 10-inch (254 mm) gun M1888 |

disappearing M1896 | 1899–1917 |

| Talbot | 2 | 4.72-inch (120 mm) Armstrong gun |

pedestal | 1899–1919 |

| unnamed | 1 | 8-inch (203 mm) gun M1888 | converted Rodman carriage | 1898–1899? |

| Bankhead | 3 | 6-inch (152 mm) Armstrong gun |

pedestal | 1907–1913 |

| Belton | 2 | 3-inch (76.2 mm) gun M1903 | pedestal M1903 | 1907–1925 |

Batteries Greene-Edgerton, Reilly, and Talbot were built between 1896 and 1899 and were the first of these to be completed. Battery Greene-Edgerton included sixteen mortars, all of which were at first called Battery Greene, but the battery was divided into two groups of eight in 1906. Battery Talbot, one of a number of batteries added on the

Battery Greene-Edgerton was named for Major General

In 1913 Battery Bankhead was disarmed and its three 6-inch (152 mm) guns sent to Hawaii.[11]

World War I

The United States entered

The two 10-inch (254 mm) guns of Battery Reilly were dismounted in 1917 for potential service as railway guns, but after considerable delay they were sent to Fort Warren near Boston, Massachusetts, in 1919 to replace guns removed from that fort. Eight of the sixteen mortars at Battery Greene-Edgerton were removed in 1918 for potential railway artillery service; this was also done as a force-wide program to improve the rate of fire due to overcrowding in the mortar pits during reloading.[11]

Some sources state that Battery Talbot's guns were redeployed to

World War I ended on 11 November 1918. With the war over, Battery Talbot was disarmed in 1919 and its guns sent to Newport and Westerly as memorials. At some time after the war three

World War II

In the Second World War a peak strength of over 3,000 soldiers were assigned to the

State Park

In 1953, the U.S. Army transferred ownership of Fort Adams to the U.S. Navy, which still uses some of the grounds for family housing[citation needed]. President Dwight D. Eisenhower lived at the former commanding officer's quarters (now called the Eisenhower House) during his summer vacations in Newport in 1958 and 1960.

From the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, Fort Adams fell victim to neglect, the weather, and vandalism. In 1965, the fort and most of the surrounding land was given to the State of Rhode Island for use as Fort Adams State Park. In 1976, Fort Adams was declared a National Historic Landmark in recognition of its distinctive military architecture, which includes features not found in other forts of the period.[24] Through the efforts of State Senator Eric O'D. Taylor, in the 1970s Fort Adams was cleaned up, opened for tours, and used for the filming of the PBS television miniseries The Scarlet Letter. The tour program was cancelled circa 1980 due to budget cutbacks by the State of Rhode Island. Since 1981, the Fort Adams grounds have been host to the Newport Jazz Festival and the Newport Folk Festival.

In the early 1990s, Fort Adams was subjected to an environmental remediation program which made the fort safe for public access. In 1994, the Fort Adams Trust was formed; to provide guided tours at the fort and oversee restoration work there. In 1995 the Fort Adams Trust began giving tours at the fort from May to September. Since that time, the fort has had several areas of the fort restored as well as having its land defenses cleared of overgrowth, and the trust's restoration efforts are ongoing..

In 2012, the park was the official venue for the America's Cup World Series in Newport.

Notable persons associated with Fort Adams

- Robert Anderson – Commander of Fort Sumter and Civil War general

- West Point.

- Alexander Dallas Bache – Army engineer and second superintendent of the United States Coast Survey.

- Pierre G. T. Beauregard– Confederate Civil War general.

- Simon Bernard – French army general, military engineer under Napoleon and designer of Fort Adams.

- Ambrose Burnside – Civil War general, Governor of Rhode Island and United States Senator.

- Dwight Eisenhower.

- West Point.

- Henry A. du Pont – Medal of Honor recipient, president of the Wilmington & Northern Railroad Company and United States Senator.

- Dwight Eisenhower– Vacationed at Fort Adams while he was president.

- William P. Ennis – Army lieutenant general born at Fort Adams.

- Robley D. Evans – Navy rear admiral and commander of the Great White Fleet.

- John G. Foster – Civil War general.

- William Gates – long serving Army officer.

- John Henry – First commander of Fort Adams and adventurer.

- Henry Jackson Hunt – Civil War general and artillery commander at the Battle of Gettysburg.

- Lyman Lemnitzer – Army general and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- John B. Magruder – Confederate Civil War general.

- Franklin Pierce – General, Senator and President of the United States.

- William S. Rosecrans– Civil War general.

- Isaac Ingalls Stevens– Civil War general.

- Thomas W. Sherman – Civil War general.

- Joseph G. Totten– Oversaw construction of Fort Adams and Chief Engineer of the United States Army.

- Louis de Tousard – Revolutionary War hero and designer of the first Fort Adams.

- Thornton Wilder – Author. Parts of his book Theophilus North were inspired by his experiences while stationed at Fort Adams during the First World War.

- William Griffith Wilson – Best known as "Bill W". Founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. Stationed at Fort Adams during the First World War.

Gallery

-

Entrance, 1968

-

1968

-

Tunnel

-

Fort Adams in 2008

-

Postcard view

See also

- 10th Coast Artillery (United States)

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- Naval Station Newport

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Rhode Island

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Newport County, Rhode Island

References

This article has an unclear citation style. (January 2019) |

- ISBN 9781625850584. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ^ "Fort Adams". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ Wade, p. 141

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, pp. 23–24

- ^ Wade, p. 242

- ^ a b Weaver, pp. 120–133

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, pp. 32–35

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, p. 27

- ^ Ann Johnson, "Material Experiments: Environment and Engineering Institutions in the Early American Republic," Osiris, NS 24 (2009), 53–74.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i FortWiki article on Fort Adams

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, pp. 37–40

- ^ a b c Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, pp. 154–156

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, pp. 44–46

- ^ a b c d Berhow, p. 204

- ^ Berhow, p. 233

- ^ Arlington Cemetery entry for Henry J. Reilly (1845–1900)

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, pp. 146–147

- ISBN 0-9720296-4-8.

- ^ History of the Coast Artillery Corps in World War I

- Chief of Ordnance, Entry 712

- ^ Duchesneau and Troost-Cramer, p. 167

- ^ Schroder, p. 120

- ^ "NHL nomination for Fort Adams". National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

Bibliography

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Second ed.). CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Schroder, Walter K. (1980). Defenses of Narragansett Bay in World War II. East Greenwich, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society. ISBN 0-917012-22-4.

- Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794–1815. CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

- Weaver II, John R. (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867, 2nd Ed. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.

External links

- Official website

- Fort Adams at FortWiki

- Fort Adams, Newport Neck, Newport, Newport, RI at the Historic American Engineering Record(HAER)

- Fort Tours: Fort Adams, RI

- Report on the Restoration of Fort Adams II prepared by William B. Robinson Archived 2018-10-22 at the Wayback Machine from the Rhode Island State Archives