Franciscan Missions in the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro

| Franciscan Missions in the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro | |

|---|---|

Franciscan Order | |

| Restored | 1990s |

Latin America and the Caribbean | |

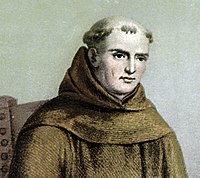

The Franciscan missions of the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro are five missions built in Mexico between 1750 and 1760. The foundation of the missions is attributed to Junípero Serra, who also founded the most important missions in California. They were declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2003.

They are an example of an architectural and stylistic unity with a tempera painting that is one of the best examples of popular New Spain Baroque. According to the criteria to which the UNESCO inscription as a World Heritage Site refers, the missions are testimony to the important exchange of values during the colonization process, both in the center and north of Mexico and in the west of what currently occupies the territory of the United States.

Region

The

All of the Sierra Gorda is marked by very rugged terrain, which includes canyons and steep mountains. Altitudes range from just 300 meters above sea level in the Río Santa María Canyon in Jalpan to 3,100 masl at the Cerro de la Pingüica in Pinal de Amoles.

Foundation

Although the mission of Jalpan was founded in 1750 before Junípero Serra arrived in the region, he is credited with building the five main missions in the area and completing the evangelization of the local population.[3] In reality, the missions were built by the Pame people, under the direction of various Franciscan friars, including José Antonio de Murguía in San Miguel Conca, Juan Crispi in Tilaco, Juan Ramos de Lora in Tancoyol, and Miguel de la Campa de Landa.

However, the vision for the construction of the missions belonged to Serra, as he imagined a kind of utopia based on Franciscan principles, Serra put a firm missionary attitude that consisted in the accompaniment and understanding of its social problems, in the knowledge of their hunger and their language; Serra founded cooperatives, supported and strengthened their organization and production capacities, motivated the distribution of land and imposed doctrinal tasks in the Pame language. It was a missionary task of great dimensions and profound consequences from the human point of view and whose results are today appreciable in the Baroque syncretism that it exhibits in all the missions.

History

Although there had been some city building in this area during the

Efforts to dominate the region included evangelization efforts, many of which failed before the mid 18th century. During the 16th and 17th century, there were attempts to evangelize the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro by the

In 1740, the colonial government decided to exterminate indigenous resistance here to secure trade routes to Guanajuato and Zacatecas. This was accomplished by

Junípero Serra spent eight years on the project of building the missions until 1770, when a number of historical events, including the expulsion of the

In the 1980s, a group from the

Architecture

The main characteristic of these temples is the rich decoration of the main doors, this decoration is called "New Spanish Baroque" or "mestizo Baroque", according to the INAH. The rich decoration is mainly aimed at teaching the new religion to the indigenous peoples, but unlike the Baroque of the temples and works further south, the indigenous influence is obvious. The idea of Serra was to demonstrate a mixture of cultures instead of a complete conquest.[3] One of them was the use of the colors red, orange and yellow, as well as pastel shades, and of sacred native figures, such as the rabbit and the jaguar. The temples have a single nave, covered by a barrel vault, but each one has its own peculiarities, especially in the portals.[3] Serra spent eleven years in the Sierra Gorda, before moving to the north, around 1760. The missions established in Querétaro would be the first in a long series of missions that would be established in what is now southern California.

The Sierra Gorda missions have unique characteristics in New Spanish Baroque, both for their conceptions of floor plans and elevations.[14] On their facades they present a series of very original compositions based on high-quality decorative elements and ingenious design; its forms are armed with partitions covered with stucco, made of quicklime burned on site and colored with earth.[14] Despite the fact that these missions were established in the 18th century, in them some basic elements of the religious architecture of the Mendicant orders of the 16th century are discovered.[14] The architecture of these missions obeys the so-called "moderate trace" program that was implemented in the 16th century and accepted by the Franciscan, Augustinian and Dominican orders; and that they applied in the convent-fortresses.[14]

The missions have what is called a Capilla posa, one of the architectural solutions used in the monastery complexes of New Spain in the 16th century, consisting of four quadrangular vaulted buildings located at the ends of the atrium outside them. Like the Capilla abierta, it is a unique solution and a contribution of Spanish-American colonial art to universal art given its originality and the plastic and stylistic resources used in its ornamentation. There are several theories about its function. It has been proposed that, following the processional path, the Capillas posas were used to pose or rest the Blessed Sacrament when it was carried in procession through the atrium.

-

Habsburg double headed eagle on the facade of the Concá mission

-

Capilla posa at the Mission of Nuestra Señora de la Luz de Tancoyol

-

Atrium and capillas posas in the Mission of San Francisco de Asís del Valle de Tilaco

Missions

The Santiago de Jalpan mission was established before the arrival of Junípero Serra in 1744, but Serra was in charge of building the mission complex that stands today from 1751 to 1758, the first to be built. It is dedicated to

The facade is elaborately done in stucco and stone work, with ochre of the

-

Inside the mission.

-

Main facade.

-

Bell tower.

-

Main dome, interior.

-

Main altar.

A second mission is located in the community of Tancoyol called Nuestra Señora de la Luz de Tancoyol, dedicated to Our Lady of Light. This facade has profuse vegetative ornamentation, with ears of corn prominent and is the most elaborate of the five missions.[3][6] It is likely that this mission was constructed by Juan Ramos de Lora, who resided here from 1761 to 1767.[3][13] The structure is similar to those in Jalpan and Landa. It has a church with a Latin cross layout and choir area, a sacristy, atrium with cross and chapels in the corners of the atrium called "capillas posas." There is also a pilgrims' gate, a cloister and quarters for the priest.

The interior has a number of sculptures including one of "Our Lady of Light."

The pediment contains a large cross in relief of two styles related to the Franciscan and Dominican orders.

-

Inside the mission.

-

Main facade.

-

Bell tower.

-

Baptistery.

-

Main altar.

-

Main dome, interior.

San Miguel Concá mission is located forty km from Jalpan on Highway 69 to Río Verde. The church is in the center of the community on one side of Guerrero Street. It is oriented to the south and dedicated to the

-

Inside the mission.

-

Main facade.

-

Baptistery.

-

Main altar.

-

Main dome, interior.

San Francisco de Asís del Valle de Tilaco mission is in a small community eighteen km northeast of Landa de Matamoros.[3] It was constructed between 1754 and 1762 by Juan Crespi and dedicated to Francis of Assisi .[12] It has some characteristics different from the other missions. First, it is built on a gradient.[10] The bell tower is separated from the main nave of the church by the baptistery and structurally functions as a buttress for the church.[3] Tilaco is the best conserved of the five missions and has the most subtle ornamentation on its facade.[12] Its facades are composed of three horizontal and three vertical partitions, with the Franciscan coat of arms prominent over the main entrance.[10] In Tilaco, the facade has small angels, ears of corn and a strange large jar over which is an image of Francis of Assisi.[6] One distinctive decorative element is four mermaids with indigenous features. Tilaco has the best conserved atrium corner chapels called "capillas posas," which were used for processions.[12]

-

Interior of the mission.

-

Main facade.

-

Bell tower.

-

Main altar.

-

Main dome, interior.

Santa María de la Purísima Concepción del Agua de Landa mission is located twenty km from Jalpan on Highway 120 towards Xilitla. The mission was built between 1760 and 1768 by Miguel de la Campa is dedicated to

The facade bears a great resemblance to that of Jalpan, in various aspects, its sizes and aesthetics, the atrium is surrounded by a wall and centered by a cross, and paved. In addition to them, the Franciscan friars leave an unprecedented rubric and the notorious reflection of their predilections in the last of their missions, there we have seen through his mother, the Immaculate Conception, Saint Francis and the four saints of the column of observance, to Archangel Michael and those studies and protectors of the order, Duns Escoto and María de Agreda. We see the universal church with Saint Peter and Paul and Christ in these three martyrs, as well as the shields of the Franciscans.

Inside we have medallions on the ceiling of the main nave beginning with Saint Michael the Archangel, with his traditional iconography, followed by Juan Duns Escoto exposed in a very didactic way presented with his hands holding the Immaculate Conception in one and a same pen with which through writing he tirelessly defended the dogma of Mary. And again Archangel Michael account to the center of the transept of two other archangels, Raphael and Gabriel.

It stands out for its balanced composition and very narrow bell tower, which is integrated into the façade. The sculpture on this facade is considered the best of the five according to the Mexican Archeology magazine.

-

Inside the mission.

-

Main facade.

-

Bell tower.

-

Bapstistery.

-

Main dome, interior.

See also

References

- ^ "Grupo Ecológico Sierra Gorda" [Sierra Gorda Ecological Group] (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Velasco Mireles, Margarita (Jan–Feb 2006). "El mundo de la Sierra Gorda" [The World of the Sierra Gorda]. Arqueología Mexicana. 77 (in Spanish). XIII. Mexico City: Editorial Raíces S.A. de C.V.: 28–37. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Cornejo, Josué (Jan–Feb 2006). "La Sierra Gorda de Querétaro" [The Sierra Gorda of Querétaro]. Arqueología Mexicana. 77 (in Spanish). XIII. Mexico City: Editorial Raíces S.A. de C.V.: 54–63. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Poblaciones pre Hispanicas, misiones franciscana y biodiversidad en la Sierra Gorda" [Pre Hispanic populations, Franciscan missions and biodiversity in the Sierra Gorda] (in Spanish). Mexico: INDAABIN. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Jalpan de Serra". México Desconocido.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gonz, Eduardo. "Las misiones de la Sierra Gorda, Querétaro" [The misión of the Sierra Gorda, Querétaro] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Estado de Guanajuato - Xichú" [State of Guanajuato - Xichú]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Estado de Hidalgo - Zimapán" [State of Hidalgo - Zimapán]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ INAH. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Édgar Rogelio Reyes (December 5, 2009). "Sierra Gorda Queretana" [Sierra Gorda of Querétano]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Misiones en la Sierra Gorda de Querétaro" [Missions in the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro]. Terra (in Spanish). Mexico City. January 14, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Misiones Franciscanas en la Sierra Gorda de Querétaro" [Franciscan Mission in the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro]. El Informador (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. March 14, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "LAS MISIONES FRANCISCANAS DE LA SIERRA GORDA". Fundación Serra.

- ^ a b c Robles, Daniel (May 12, 2002). "Desfile de santos en el Mexico profundo" [Parade of saints deep in Mexico]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d "Circuito Misionero" [Missionary Circuit] (in Spanish). Mexico: Municipality of Jalpan de Serra. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Querétaro - Jalpan de Serra" [Querétaro – Jalpan de Serra]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2011.