Gianni Rivera

Giovanni Rivera | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Member of European Parliament | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 May 2005 – 13 July 2009 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | North-West Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 2 July 1987 – 29 May 2001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constituency | Milan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 18 August 1943 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

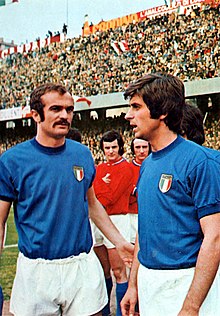

Giovanni "Gianni" Rivera (Italian pronunciation:

Dubbed Italy's "Golden Boy" by the media, he played the majority of his club career with Italian side

At international level, Rivera represented

Rivera was an elegant, efficient, and creative offensive

After retiring from football in 1979, Rivera became Milan's vice-president and later went into politics in

Early life

Rivera was born in Alessandria, Piedmont, to Edera and Teresio; his father was a railway worker. Gianni began playing football with local side ASD Don Bosco, where he was scouted by former Milan midfielder Franco Pedroni, who was the assistant coach at Alessandria at the time, prompting Rivera to join the local Serie A side at the age of 13.[1][2][7][8][9][22]

Club career

1959–1962: Debut with Alessandria, early years with AC Milan and first scudetto

"He's an elegant young player with a remarkable touch."

— Giuseppe Meazza comments on Rivera after watching him play with Milan for the first time.[2]

Nicknamed l'Abatino, and the Golden Boy of Italian football throughout his career,

Rivera made his Milan debut on 18 September 1960, in a 3–5 away win over his former club Alessandria in the

1962–1970: International successes with AC Milan

Rivera's 1962 scudetto victory with Milan under Nereo Rocco enabled the team to qualify for the

In the

1970–1979: Later years with AC Milan

In the 70s, Rivera's continued strong performances led Milan on to two more

Following Rocco's second departure from the club in 1973, the club's management attempted to persuade Rivera to leave Milan, although Rivera ultimately chose to remain with the club.

International career

Early years

Rivera was a part of the

With the Italian senior side, Rivera made his debut on 13 May 1962 in a 3–1 away win against

Rivera was later also included in Italy's squad for the

1970 World Cup

Rivera subsequently played with the Squadra Azzurra (Italy national team) in the 1970 FIFA World Cup hosted by Mexico. At the prime of his career, much was expected of him throughout the tournament; after a slow start, his excellent form in the knock-out stages saw him become Italy's star player throughout the competition, as they reached the final, only to lose out 4–1 to a Pelé-led Brazil side.[7] Prior to the tournament, the Italian team was thrown into turmoil following Pietro Anastasi's last-minute injury, which ruled the striker out of the competition; Roberto Boninsegna and Pierino Prati were called up in his place, while Giovanni Lodetti, who was Rivera's midfield partner and defensive foil at Milan, was dropped from the team; as a result, Rivera was at the centre of controversy when he accused the Italy national team supervisor Walter Mandelli of leading a media campaign against him, and of also wanting to exclude him from the team, which only put his place on the team in further jeopardy.[1][43][44][45] Furthermore, the Italian coach at the 1970 World Cup Finals, Ferruccio Valcareggi, believed that Rivera and his fellow right-sided playmaker teammate Sandro Mazzola could not play together on the same field, as they played in similar positions for rival clubs. Although Rivera was arguably the more famous of the two stars at the time, as the reigning European Footballer of the Year, Valcareggi elected to start Mazzola, due to his pace, stamina, superior work rate, and stronger physical and athletic attributes, which he deemed more important in the tournament, and Rivera missed out on Italy's opening two group matches, with his absence being blamed on "stomach troubles"; he made his first appearance of the tournament in Italy's final group match, a 0–0 draw against Israel on 11 June, coming on for Angelo Domenghini. Due to Rivera's frequent arguments with the Italian coaching staff over his limited playing time, his mentor Rocco had to be flown in to prevent him from leaving the squad.[1][7][42][45][46][47]

By the second round of the tournament, however, the Italian offence failed to sparkle. Although Rivera's playing style involved less running, physicality, tactical discipline, and work off the ball than Mazzola's, and made Italy less compact and more vulnerable defensively, it also allowed his team to control possession in midfield, due to Rivera's ability to dictate the play with his passing moves, provide accurate long passes, and create more chances for the team's strikers. When Mazzola came down with a stomach flu, and struggled to regain full match fitness for the knock-out round, Valcareggi therefore devised a controversial solution to play both players and get the best out of their abilities: the quicker and more hard-working Mazzola would start in the first half, while Rivera would come on at halftime, when the opposing teams would begin to tire, and the tempo of the game had slowed down, giving him more time to orchestrate goal scoring opportunities; this strategy was later dubbed the "staffetta" (

"I told myself, there's no other alternative for me but to get the ball, take it past everyone and score."

— Rivera on his mental state following his error which led to West Germany's temporary equaliser in extra-time of the 1970 World Cup semi-final, and ahead of his match-winning goal one minute later.[1]

In the semi-final against West Germany, at the Estadio Azteca on 17 June, Rivera played a major role in one of the most entertaining games in World Cup history, a match which was later dubbed The Game of the Century. Following a 1–1 draw after regulation time, Rivera's long passes led to Tarcisio Burgnich's and Luigi Riva's goals in extra-time, although he was later also at fault for Germany's equaliser; while defending against a German set-piece, Rivera briefly stepped away from the post, leaving it unmarked, and allowing Gerd Müller to score his second goal and tie the match at 3–3 in the 110th minute, which famously led Italy's temperamental goalkeeper Enrico Albertosi to berate Rivera for the error. A minute later, however, Rivera started an attacking play from the ensuing kick-off, a move which he eventually proceeded to finish off himself, scoring Italy's match-winning goal from Roberto Boninsegna's low cross to give Italy a 4–3 victory, after advancing into the penalty area unmarked, and sending German goalkeeper Sepp Maier the wrong way with his first-time shot.[1][2][8][9][43][44][45][46][50][53]

"I was worried that Rivera would come on, I thought that with Rivera Italy would be more dangerous."

—

However, despite Rivera being the hero of Italy's past two matches, in the

Later years

"Rivera, Rivera, Rivera, Rivera."

— England manager Alf Ramsey's response when asked to name the four strongest Italian players following Italy's 1–0 win over England in a friendly match at Wembley Stadium on 14 November 1973.[1][55][56][57][58]

Rivera also played in the

Retirement

Milan vice-president

After retirement, Rivera became a vice-president at Milan for seven seasons. When Silvio Berlusconi bought the club in 1986, he resigned from his position and entered politics.[7][8]

Political career

Rivera started his career in politics in 1986, becoming a member of the

FIGC President

In 2013 Rivera was appointed by the Italian Football Federation (FIGC) as President of the Technical Sector (settore tecnico), which oversees the training and qualification of technical staff employed by the FIGC and is headquartered at the Coverciano in Florence.[8][62]

Player profile

Style of play

"Yes, he doesn't run a lot, but if I want good football, creativity, the art of turning around a situation from the first to the ninetieth minute, only Rivera can give me all of this with his flashes. I wouldn't want to exaggerate, because in the end it's only football, but Rivera in all of this is a genius."

— Nereo Rocco on Rivera.[26]

Rivera was a graceful, creative, technically gifted, and efficient offensive midfield playmaker, who possessed exceptional footballing intelligence, and class.[1][2][7][63] Rivera was capable of playing anywhere in midfield or along the front line, but he was usually used in a free role, either as a deep-lying playmaker in central midfield, as an offensive–minded central midfielder (known as the "mezzala" role, in Italian), or most frequently as a classic number 10 behind the forward; he was also deployed as a deep-lying or inside forward on occasion, and at the beginning of his career, he was even occasionally used in a central role as a main striker, while at Alessandria, and as a winger on either flank, with the Italian Olympic side, in particular on the right side of the pitch.[1][2][3][24][63][64][65] Although he was not known for his defensive abilities, and lacked both notable stamina and pace, as well as significant physical and athletic attributes due to his small stature and slender build,[44][64][66] he was an extremely talented right-footed player, who was renowned for his vision, tactical intelligence, and his skilful yet effective style of play, despite his poor defensive work-rate.[1][2][9][64][67]

Rivera was highly regarded for his outstanding ball control,

"You watch footage from those years now and everyone seems slower than now, Rivera perhaps slower still and keeping the ball too much, but his forte was in spraying inspired passes around and always going forward, with a more than average eye for goal for a midfielder..."

— ESPN columnist Roberto Gotta on Rivera's playing style.[44]

Despite being primarily a creative midfielder, and a team player, who preferred assisting teammates over scoring goals himself, Rivera was also known for his ability to make attacking runs and for his keen eye for goal;

Reception and legacy

"[Rivera] was ... one of the greatest passers of all time who was known for his impeccable dribbling and distribution. In addition, Gianni Rivera was a true gentleman, both on and off the field of play, and he has remained so to this day."

— Michel Platini speaking on Rivera being honoured with the UEFA President's Award in 2011.[68]

Regarded as one of Italy's and Milan's greatest ever footballers, one of the best players of his generation, one of the best midfielders in history, and one of the most talented advanced playmakers of all time,

Outside of professional football

AIC

On 3 July 1968, Rivera founded the Italian Footballers' Association (AIC), in Milan, along with several fellow footballers, such as Giacomo Bulgarelli, Sandro Mazzola, Ernesto Castano, Giancarlo De Sisti, and Giacomo Losi, as well as the recently retired Sergio Campana, also a lawyer, who was appointed president of the association.[75]

Personal life

Rivera is married to Laura Marconi; together they have two children: Chantal (born in 1994) and Gianni (born in 1996). He has another daughter, Nicole (born in 1977), with the Italian former actress and television personality Elisabetta Viviani, with whom he was in a relationship at the time.[1][8]

Media

Rivera is featured in the EA Sports football video games FIFA 11, FIFA 14 and FIFA 15's Classic XI – a multi-national all-star team, along with compatriots Bruno Conti, Giacinto Facchetti, and Franco Baresi.[76]

In 2012, Rivera took part in the eighth season of

Career statistics

Club

| Club | Season | League | Cup | Europe[nb 1] | Other[nb 2] | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Alessandria | 1958–59

|

1 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 0 |

1959–60

|

25 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 25 | 6 | |

| Total | 26 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 26 | 6 | |

AC Milan

|

1960–61 | 30 | 6 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 2 | 0 | 33 | 6 |

| 1961–62 | 27 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | – | – | 30 | 10 | |

| 1962–63 | 27 | 9 | – | – | 7 | 2 | – | – | 34 | 11 | |

| 1963–64 | 27 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 32 | 8 | |

| 1964–65 | 29 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 29 | 2 | |

| 1965–66 | 31 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | – | – | 36 | 8 | |

| 1966–67 | 34 | 12 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 43 | 19 | |

| 1967–68 | 29 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 1 | – | – | 44 | 15 | |

| 1968–69 | 28 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | – | – | 39 | 6 | |

| 1969–70 | 25 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 12 | |

| 1970–71 | 26 | 6 | 10 | 7 | – | – | – | – | 36 | 13 | |

| 1971–72 | 23 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 4 | – | – | 37 | 9 | |

| 1972–73 | 28 | 17 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 0 | – | – | 43 | 20 | |

| 1973–74 | 26 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0 | – | – | 39 | 7 | |

| 1974–75 | 27 | 3 | 4 | 0 | – | – | – | – | 31 | 3 | |

| 1975–76 | 14 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0 | – | – | 22 | 2 | |

| 1976–77 | 27 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 0 | – | – | 39 | 4 | |

| 1977–78 | 30 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 36 | 7 | |

| 1978–79 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | – | – | 22 | 2 | |

| Total | 501 | 122 | 74 | 28 | 76 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 658 | 164 | |

| Career total | 527 | 128 | 74 | 28 | 76 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 684 | 170 | |

International

| National team | Year | Apps | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 1962 | 4 | 2 |

| 1963 | 5 | 2 | |

| 1964 | 4 | 2 | |

| 1965 | 6 | 1 | |

| 1966 | 6 | 2 | |

| 1967 | 4 | 0 | |

| 1968 | 4 | 0 | |

| 1969 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1970 | 7 | 2 | |

| 1971 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1972 | 3 | 0 | |

| 1973 | 7 | 2 | |

| 1974 | 4 | 1 | |

| Total | 60 | 14 | |

Honours

- Serie A: 1961–62, 1967–68, 1978–79

- Coppa Italia: 1966–67, 1971–72, 1972–73, 1976–77

- 1968–69

- 1972–73

- Intercontinental Cup: 1969

- FIFA World Cup runner-up: 1970

- UEFA European Championship: 1968

Individual

- Coppa Italia top scorer: 1966–67, 1970–71[80]

- Ballon d'Or: 1969,[37] runner-up 1963[2][30]

- FIFA XI: 1967[81]

- FUWO European Team of the Season: 1969[82], 1970[83]

- IFFHS Italian Player of the 20th Century: 1999[15]

- IFFHS European Player of the 20th Century (12th): 1999[15]

- IFFHS World Player of the 20th Century: (19th)[15]

- AC Milan Player of the 20th Century: 1999[1][35]

- Golden Foot "Football Legends": 2003[85]

- FIFA 100[17]

- UEFA Golden Jubilee Poll: No. 35[18][86]

- AC Milan Hall of Fame[30]

- UEFA President's Award: 2011[32][87]

- Inducted into the Italian Football Hall of Fame: 2013[8][88]

- Inducted into the Walk of Fame of Italian sport: 2015[16][89]

Notes

- UEFA Cup, and European Super Cup

- ^ Includes the Intercontinental Cup, Coppa dell'Amicizia, and Cup of the Alps

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az "Gianni Rivera: Golden Boy" (in Italian). Maglia Rossonera.it. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Milan and Italy's golden boy: Gianni Rivera". FIFA. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ a b c "Rivera, Gianni" (in Italian). TuttoCalciatori. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "Convocazioni e presenze in campo: Gianni Rivera". figc.it (in Italian). FIGC. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Gianni Rivera at National-Football-Teams.com

- ^ "Gianni Rivera". Olympedia. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "Legend of Calcio: Gianni Rivera". forzaitalianfootball.com. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Gianni Rivera" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Gianni Rivera: La leggenda del Golden Boy" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Max Towle (9 May 2013). "25 Most Skilled Passers in World Football History". bleacherreport.com. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Baggio, Sacchi e Rivera Figc ufficializza le nomine" (in Italian). Il Corriere dello Sport. 4 August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Marcelo Leme de Arruda (21 January 2000). "IFFHS' Players and Keepers of the Century for many countries". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b Manlio Gasparotto (15 August 2015). "La Gazzetta dello Sport vota Rivera: è il miglior calciatore italiano di tutti i tempi" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Nicolè, il bel centrattacco che pesava troppo: "Il calcio? Dimenticato"" (in Italian). La Repubblica. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Karel Stokkermans (30 January 2000). "IFFHS' Century Elections: World – Player of the Century". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b c "Inaugurata la Walk of Fame: 100 targhe per celebrare le leggende dello sport italiano" (in Italian). Coni. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b c "Pele's list of the greatest". BBC Sport. 4 March 2004. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Erik Garin; Rui Silva (21 December 2006). "The UEFA Golden Jubilee Poll". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Serie a News - the biggest Italian football news site". Football Italia. Retrieved 31 December 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ David Swan (29 January 2013). "Roberto Baggio's ignored vision". Football Italia. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Prandelli: "we have to work on playing intensity for european competitions"". FIGC. 15 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gianni Mura (18 August 2013). "Il calcio al tempo di Rivera ragazzo d'oro dell'Italia felice" (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Gianni Rivera, il "golden boy" del calcio italiano". Panorama (in Italian). 14 August 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gianni Brera (19 February 2016). "Gianni Brera: "Rivera, rendimi il mio Abatino…"" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Ben Gladwell (23 December 2016). "Genoa's Pietro Pellegri makes debut aged 15, equals Serie A record". ESPN FC. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ a b "RIVERA Gianni: Golden Boy per sempre – 1" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Piero Bottino (26 January 2016). "Rivera, il simbolo amato e odiato che divide la città". La Stampa (in Italian). Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Rivera, Gianni" (in Italian). MuseoGrigio.it. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ FRANCESCO SAVERIO INTORCIA (21 November 2015). "Gianni Rivera: "A 17 anni segnai il gol del 4–3 alla Juve: era il mio destino"" (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "AC Milan Hall of Fame: Gianni Rivera". A.C.Milan.com. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ a b "RIVERA Gianni: Golden Boy per sempre – 2" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Award winner Rivera happy with his legacy". UEFA. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "RIVERA, Gianni" (in Italian). Treccani: Enciclopedia dello Sport (2002). Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ "King-less Santos retain throne in style". FIFA. 16 November 2013. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Andrea Masala (15 December 1999). "Cento Milan, 37 successi" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Campionato di Calcio Serie A: record, primati, numeri e statistiche". Il Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). 30 October 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Gianni Rivera". FIFA. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Addio Bulgarelli, bandiera del Bologna" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "2 dicembre 1962: il primo gol azzurro di Gianni Rivera" (in Italian). VivoAzzurro.it. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Luca Stamerra (23 March 2019). "Italia, Moise Kean nella storia: è il secondo più giovane di sempre a segnare in Nazionale" (in Italian). eurosport.com. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Clarke, James (29 July 2016). "1966 World Cup: England's tournament behind the scenes – BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Aldo Cazzullo (26 November 2016). "Rivera: "Da ragazzo ero juventino e Brera mi riportò in Nazionale"" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Sebastiano Vernazza (30 April 2014). "Nazionale, Rivera, rivalità e gol Italia-Germania 4–3 è la partita del secolo" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Roberto Gotta (4 January 2004). "Tales from the Rivera bank". ESPN FC. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Gianni De Felice (19 December 2015). "1970: Quando perdemmo le… staffette" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Joy and pain as Rivera settles Game of the Century". FIFA. 15 September 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ a b c GIANNI BRERA (30 May 1986). "VIGILIA MUNDIAL PENSANDO AL '70" (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ MAURIZIO CROSETTI (3 November 2005). "Esce Mazzola, entra Rivera così la staffetta ha fatto storia" (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "70 anni di Rivera: gli auguri di Mazzola". Panorama (in Italian). 14 August 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ a b John F. Molinaro (21 November 2009). "1970 World Cup: Pele takes his final bow". CBC Sports. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Gianni Brera (4 March 1988). "Gianni Brera: Italia 1970 vs Italia 1982" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Gianni Rivera (4 March 1988). "EPPURE VALCAREGGI AVEVA RAGIONE..." (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ Diego Mariottini (17 June 2015). "Italia-Germania 4–3: la brutta partita che fece la storia" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Messico 70 e quei 6 minuti che sconvolsero l'Italia" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. 17 November 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ISBN 978-1568586526.

- ^ "Un tocco di Capello e l'Inghilterra è servita" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Anche il Briamasco nell'antologia" (in Italian). Il Trentino. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ Francesca Fanelli (14 November 2011). "1973, Mitico Capello-gol: l'Italia vince in Inghilterra" (in Italian). Il Corriere dello Sport. Retrieved 4 December 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Simon Burnton (29 April 2014). "World Cup: 25 stunning moments ... No12: Haiti stun Dino Zoff's Italy". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Nazionale, De Rossi raggiunge le 100 presenze" [National team, De Rossi reaches 100 appearances] (in Italian). Il Corriere dello Sport. 1 November 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ a b Jonathan Wilson (27 May 2014). "100 top World Cup footballers: No100 to No61". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- FIGC. 28 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Dave Taylor (9 March 2014). "Italy's All-Time No 10s". Football Italia. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ a b c MAURIZIO CROSETTI (29 October 1991). "IL BAGGIO PERDUTO" (in Italian). La Repubblica. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ a b Maggioni, Enrico. "GIANNI RIVERA" (in Italian). Pianeta Milan. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "AC Milan and Italian Golden Boy: Gianni Rivera". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Edd Norval (11 September 2018). "Gianni Rivera: the greatest playmaker in AC Milan history". thesefootballtimes.co. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Gianni Rivera to receive UEFA President's Award". UEFA. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Rivera: Premiato da Platini" (in Italian). Calcio Mercato.com. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Max Towle (9 May 2013). "25 Most Skilled Passers in World Football History". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-4722-2705-8.

- ^ "I 10 migliori rigoristi della storia della Serie A". 4 September 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b Tighe, Sam (19 March 2013). "50 Greatest Midfielders in the History of World Football". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Dalla A alla Zico, i grandi numeri 10 del calcio internazionale" (in Italian). Sport.Sky.it. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "La storia". assocalciatori.it (in Italian). Associazione Italiana Calciatori. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "FIFA 14 Classic XI". Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Marida Caterini. "Torna Ballando con le stelle, nel cast Bobo Vieri e Gianni Rivera". Panorama (in Italian). Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Roberto Di Maggio (7 December 2002). "Gianni Rivera – Goals in International Matches". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ "1969 – Gianni Rivera" (in French). France Football. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Roberto Di Maggio; Davide Rota (4 June 2015). "Italy – Coppa Italia Top Scorers". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ FIFA XI´s Matches – Full Info Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "FUWO 1970" (PDF). FCC-Wiki. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "FUWO 1971" (PDF). FCC-Wiki. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Roberto Di Maggio; Igor Kramarsic; Alberto Novello (11 June 2015). "Italy – Serie A Top Scorers". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Golden Foot Legends". Golden Foot.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Zinedine Zidane voted top player by fans" (PDF). UEFA. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "UEFA President's Award". UEFA. 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "BARESI, CAPELLO AND RIVERA ACCEPTED IN HALL OF FAME". A.C. Milan.com. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "CNA 100 Leggende CONI per data di nascita" (PDF) (in Italian). Coni. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

External links

- Gianni Rivera at FIFA (archived)

- Gianni Rivera at UEFA

- Gianni Rivera at EU-Football.info

- Gianni Rivera at FBref.com

- Gianni Rivera at National-Football-Teams.com

- Gianni Rivera at WorldFootball.net

- Gianni Rivera at Olympedia

- Gianni Rivera at FIGC (in Italian)

- Gianni Rivera at Italia1910.com (in Italian)

- Gianni Rivera at TuttoCalciatori.net (in Italian)

- FIFA Classic Player: Milan and Italy's Golden Boy at the Wayback Machine (archived 25 August 2013)