Great frigatebird

| Great frigatebird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male, displaying, with inflated gular sac | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | Fregatidae |

| Genus: | Fregata |

| Species: | F. minor

|

| Binomial name | |

| Fregata minor (Gmelin, 1789)

| |

| |

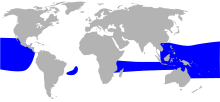

| Range map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pelecanus minor Gmelin 1789 | |

The great frigatebird (Fregata minor) is a large

The great frigatebird is a large and lightly built seabird up to 105 cm long with predominantly black plumage. The species exhibits

Taxonomy

The great frigatebird was

A Late Pleistocene fossilised wing phalanx and proximal end of humerus (indistinguishable from the extant great frigatebird) were recovered from Ulupau Head on Oahu.[9]

Subspecies

Five subspecies are usually recognised:[7]

- F. m. aldabrensis Mathews, 1914.[8] West Indian Ocean (Aldabra, Comoros, Europa Island)

- F. m. minor (J. F. Gmelin, 1789).[2] Central and East Indian Ocean to South China Sea

- F. m. palmerstoni (J. F. Gmelin, 1789).Palmyra atoll, Phoenix Islands, Line Islands including Kiritimati (Christmas Island), Marquesas Islands, Tuamotus, Society Islands, Pitcairn Islands and Isla Salas y Gómez)

- F. m. ridgwayi Mathews, 1914.[8] East Pacific Ocean (Revillagigedo Islands, Cocos Island, Galápagos Islands)

- F. m. nicolli Mathews, 1914.[8] South Atlantic (Trindade and Martim Vaz)

Description

The great frigatebird measures 85 to 105 cm (33 to 41 in) in length and has a wingspan of 205–230 cm (81–91 in).[10] Male great frigatebirds are smaller than females, but the extent of the variation varies geographically.[11] The male birds weigh 1,000–1,450 g (2.20–3.20 lb) while the heavier female birds weigh 1,215–1,590 g (2.679–3.505 lb).[12]

Frigatebirds have long narrow pointed wings and a long narrow deeply forked tail. They have the highest ratio of wing area to body mass and the lowest wing loading of any bird. This has been hypothesized to enable the birds to use marine thermals created by small differences between tropical air and water temperatures. The plumage of males is black with scapular feathers that have a green iridescence when they refract sunlight. Females are black with a white throat and breast and have a red eye ring. Juveniles are black with a rust-tinged white face, head, and throat.

Distribution and habitat

The great frigatebird has a wide distribution throughout the world's tropical seas.

Great frigatebirds undertake regular

Behaviour

Feeding

The great frigatebird forages in

Great frigatebirds will also hunt seabird chicks at their breeding colonies, taking mostly the chicks of sooty terns, spectacled terns, brown noddies, black noddies and even from other great frigatebirds.[17] Studies show that only females (adults and juveniles) hunt in this fashion, and only a few individuals account for most of the kills.[18] Great frigatebirds will also feed opportunistically in coastal areas on turtle hatchlings and fish scraps from commercial fishing operations.[17]

Great frigatebirds will attempt kleptoparasitism, chasing other nesting seabirds (boobies, tropicbirds and gadfly petrels[17] in particular) in order to make them regurgitate their food. This behaviour is not thought to play a significant part of the diet of the species, and is instead a supplement to food obtained by hunting. A study of great frigatebirds stealing from masked boobies estimated that the frigatebirds could at most obtain 40% of the food they needed, and on average obtained only 5%.[19]

Breeding

Great frigatebirds are seasonally

Both sexes have a patch of skin at the throat that is the gular sac; in male great frigatebirds this skin is red and can be inflated to attract a mate. Groups of males sit in bushes and trees and force air into their sac, causing it to inflate over a period of 20 minutes into a startling red balloon. As females fly overhead the males waggle their heads from side to side, shake their wings and call. Females will observe many groups of males before forming a pair bond. Having formed a bond the pair will sometimes select the display site, or may seek another site, to form a nesting site; once a nesting site has been established both sexes will defend their territory (the area surrounding the nest that can be reached from the nest) from other frigatebirds.

Pair bond formation and nest-building can be completed in a couple of days by some pairs and can take a couple of weeks (up to four) for other pairs. Males collect loose nesting material (twigs, vines,

A single dull chalky-white

Parental care is prolonged in great frigatebirds.

Great frigatebirds take many years to reach sexual maturity and only breed once they have acquired the full adult plumage. This is attained by female birds when they are eight to nine years of age and for male birds when they are 10 to 11 years of age.[21] The average lifespan is unknown but is assumed to be relatively long. As part of a study conducted in 2002 on Tern Island in Hawaii, 35 ringed great frigatebirds were recaptured. Of these 10 were 37 years or older and one was at least 44 years old.[22]

Status

Because of the large overall total population and extended range the species is classified by the

In the South Atlantic, great frigatebirds (subspecies F. m. nicolli) once bred on both

Gallery

-

Male in flight, Galápagos Islands

-

Juvenile male in flight

-

Female in flight

-

Another female in flight

-

Male, Galápagos Islands

-

Female, Galápagos Islands

References

- ^ . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 572.

- ^ Latham, John (1785). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 3, Part 2. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. pp. 590–591.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 161.

- ^ Edwards, George (1760). Gleanings of Natural History, Exhibiting Figures of Quadrupeds, Birds, Insects, Plants &c. Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author. Plate 309.

- PMID 15019606.

- ^ Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Storks, frigatebirds, boobies, darters, cormorants". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Mathews, GM (1914). "On the species and subspecies of the genus Fregata". Australian Avian Record. 2 (6): 120 (117–121).

- ^ James, Helen F. (1987). "A late Pleistocene avifauna from the island of Oahu, Hawaiian Islands" (PDF). Documents des laboratories de Géologie, Lyon. 99: 221–30.

- ^ a b Metz, VG; Schreiber, EA (2002). "Great Frigatebird (Fregata minor)". In Poole, A; Gill, F (eds.). The Birds of North America. Vol. 681. Philadelphia PA: The Birds of North America.

- JSTOR 1368437.

- S2CID 216406285. Retrieved 30 November 2014.(subscription required)

- S2CID 18679093.

- .

- ISBN 0-8014-2449-6

- JSTOR 1368877.

- ^ a b c d "Fregata minor (Great frigatebird)".

- JSTOR 1369150.

- JSTOR 1369318.

- ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- ^ Valle, Arlos A; de Vries, Tjitte; Hernández, Cecilia (2006). "Plumage and sexual maturation in the Great frigatebird Fregata minor in the Galapagos Islands" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 34: 51–59.

- .

- ^ S2CID 91072996.

- ^ OCLC 770307954. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- hdl:10088/12766.

- ^ ISBN 978-85-7738-102-9. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-12-11. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

Further reading

- Bastien, M; Jaeger, A; Le Corre, M; Tortosa, P; Lebarbenchon, C (2014). "Haemoproteus iwa in Great Frigatebirds (Fregata minor) in the Islands of the Western Indian Ocean". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e97185. PMID 24810172.

- Merino, S; Hennicke, J; Martìnez, J; Ludynia, K; Torres, R; Work, TM; Stroud, S; Masello, JF; Quillfeldt, P (2012). "Infection by Haemoproteus parasites in four species of frigatebirds and the description of a new species of Haemoproteus (Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae)". Journal of Parasitology. 98 (2): 388–397. S2CID 3846342.

- O'Brien, RM (1990). "Fregata minor Great Frigatebird" (PDF). In Marchant, S; Higgins, PG (eds.). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1: Ratites to ducks; Part B, Australian pelican to ducks. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 913–920. ISBN 978-019553068-1.

External links

- 'Iwa or Great Frigatebird Archived 2014-06-06 at the Wayback Machine - State of Hawaii, Division of Forestry and Wildlife

- Internet Bird Collection: photos, videos and audio recordings

- Audio recordings from xeno-canto