Great reed warbler

| Great reed warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult at a bird banding station

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Acrocephalidae |

| Genus: | Acrocephalus |

| Species: | A. arundinaceus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acrocephalus arundinaceus | |

| |

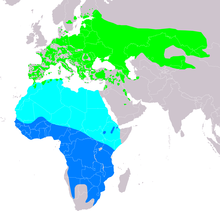

| Range of A. arundinaceus Breeding Passage Non-breeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Turdus arundinaceus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The great reed warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) is a

The genus name Acrocephalus is from Ancient Greek akros, "highest", and kephale, "head". It is possible that Naumann and Naumann thought akros meant "sharp-pointed". The specific arundinaceus is from Latin and means "like a reed", from arundo, arundinis, "reed".[3]

It used to be placed in the

Description

The

The sexes are identical, as with most old world warblers, but young birds are richer buff below.

The warbler's song is very loud and far-carrying. The song's main phrase is a chattering and creaking carr-carr-cree-cree-cree-jet-jet, to which the whistles and vocal mimicry typical of marsh warblers are added.

Distribution and ecology

The great reed warbler breeds in

While there are no

During 2017–2019, miniature data loggers were used to track migratory flights of great reed warblers, over the Mediterranean Sea and Sahara Desert, between their breeding grounds at Lake Kvismaren, Sweden, and their winter quarters in sub-Saharan Africa.[4] When over the Sahara Desert, some birds would ascend to altitudes exceeding 5 km. As of 2023, these are the highest recorded avian ascents. [10] For comparison, such altitudes are comparable to those of the summits of the highest mountains in Africa and Europe. Possible explanations for such high--altitude ascents include avoidance of predation, reduction of risk of hyperthermia and dehydration, and extension of the visual horizon.[4][10]

This

The great reed warbler undergoes marked long-term population fluctuations, and it is able to expand its range quickly when new

| Population densities of Great reed warblers (mean±SD) in European countries | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Method | Pairs/ha | Birds/ha | Nests/ha | Ref. | |||||||||||

| Spain | Transect | - | 1.4 | - | [11] | |||||||||||

| Slovakia | Nest | 6.5±6.2 | - | - | [12] | |||||||||||

| Poland | Nest | - | - | 2.5±1.8 | [13] | |||||||||||

Behaviour

Diet

A. arundinaceus has a primarily

Communication and courtship

Male great reed warblers have been observed to communicate via two basic song types: short songs about one second in length with few syllables, and long songs of about four seconds that have more syllables and are louder than the short variety. It has been observed that long songs are primarily used by males to attract females; long songs are only given spontaneously by unpaired males, and cease with the arrival of a female. Short songs, however, are primarily used in territorial encounters with rival males.[17]

During experimental observation, male great reed warblers showed reluctance to approach recordings of short songs, and when lured in by long songs, would retreat when playback was switched to short songs.[17]

Traditionally, monogamous species of genus Acrocephalus use long, variable, and complex songs to attract mates, whereas polygynous varieties use short, simple, stereotypical songs for territorial defence. There is evidence that long songs have been evolved through intersexual selection, whereas short songs have been evolved through intrasexual selection. The great reed warbler is a notable example of these selective pressures, as it is a partial polygynist and has evolved variable song structure (both long and short) through evolutionary compromise.[17]

In addition to communication, the great reed warbler's song size has been implicated in organism fitness and reproductive success. Though no direct relationship has been found between song size and either territory size or beneficial male qualities, such as wing length, weight, or age, strong correlation has been observed between repertoire size and territory quality. Furthermore, partial correlation analysis has shown that territory quality has significant effect on the number of females obtained, while repertoire length is linked to the number of young produced.[18]

Mating system and sexual behavior

Great reed warbler females lay 3–6

A long-term study of the factors that contribute to male fitness examined the characteristics of males and territories in relation to annual and lifetime breeding success. It showed that the arrival order of the male was the most significant factor for predicting pairing success, fledgling success, and number of offspring that survive. It also found that arrival order was closely correlated with territory attractiveness rank. Females seem to prefer early arriving males that occupy more attractive territories. These females also tend to gain direct benefits through the increased production of fledglings and offspring that become adults. In addition, male song repertoire length is positively correlated to annual harem size and overall lifetime production of offspring that survive. Song repertoire size alone is able to predict male lifetime number of surviving offspring. Females tend to be attracted to males with longer song repertoires since they tend to sire offspring with improved viability. In doing so, they gain indirect benefits for their own young.[22][23]

Great reed warblers have a short,

References

- ^ . Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ For instance in Gould, John (1873). The Birds of Great Britain. Vol. II. pp. Plate LXXII (and accompanying text).. See also: Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Acrocephalus turdoïdes. Thrush-Warbler., (1862 - 1873)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ "Acrocephalus arundinaceus (Linnaeus, 1758)".

- ISBN 84-87334-20-2.

- ISBN 978-0856610790.

- ^ a b Traylor, Marvin; Daniel Parelius (13 November 1967). "A Collection of Birds from the Ivory Coast". Fieldiana Zoology. 51 (7): 91–117.

- ^ .

- ^ ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ PMID 30059562.

- ^ Prokešová, J.; Kocian, L. (2004). "Habitat selection of two Acrocephalus warblers breeding in reed beds near Malacky (Western Slovakia)" (PDF). Biologia Bratislava. 59: 637–644.

- .

- S2CID 22647139.

- ^ Grzimek, Bernhard (2002). Hutchins, Jackson; Bock, Olendorf (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Vol. 11.4 (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. p. 17.

- S2CID 35524752.

- ^ S2CID 53192983.

- S2CID 32813295.

- S2CID 84661011.

- S2CID 53164964.

- PMID 31811179.

- S2CID 21645256.

- .

- JSTOR 5418.

- .