Vertebrate

| Vertebrate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diversity of vertebrates: ). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Superphylum: | Deuterostomia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Olfactores |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata J-B. Lamarck, 1801[2] |

| Infraphyla | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ossea Batsch, 1788[2] | |

Vertebrates (

Vertebrates comprise groups such as the following

- Agnatha or jawless fish, which include:

- †Conodonta

- †Ostracodermi

- lampreys)

- †

- Gnathostomata or jawed vertebrates, which include:

- †Placodermi

- †Acanthodii

- ratfish)

- Osteichthyes or bony fish, which include:

- livingvertebrates, including:

- Cladistia (bichirs and relatives)

- Chondrostei (sturgeons and paddlefish)

- Holostei (bowfins and gars)

- Teleostei(96% of living fish species)

- Sarcopterygii or lobe-finned fish, which include:

- †

The vertebrates traditionally include the

Etymology

The word vertebrate derives from the

Anatomy and morphology

All vertebrates are built along the basic chordate

Vertebral column

With only one exception, the defining characteristic of all vertebrate is the

A few vertebrates have secondarily lost this feature and retain the notochord into adulthood, such as the sturgeon[15] and coelacanth. Jawed vertebrates are typified by paired appendages (fins or limbs, which may be secondarily lost), but this trait is not required to qualify an animal as a vertebrate.

Gills

All

In

While the more derived vertebrates lack gills, the gill arches form during

Central nervous system

The

The vertebrates are the only

The rostral end of the neural tube is expanded by a thickening of the walls and expansion of the

The resulting anatomy of the central nervous system with a single hollow nerve cord dorsal to the

Another distinct neural feature of vertebrates is the

Molecular signatures

In addition to the morphological characteristics used to define vertebrates (i.e. the presence of a notochord, the development of a vertebral column from the notochord, a dorsal nerve cord, pharyngeal gills, a post-anal tail, etc.), molecular markers known as

A specific relationship between Vertebrates and

Evolutionary history

External relationships

Originally, the "Notochordata hypothesis" suggested that the

The following cladogram summarizes the systematic relationships between the Olfactores (vertebrates and tunicates) and the Cephalochordata.

| Chordata

|

| ||||||

First vertebrates

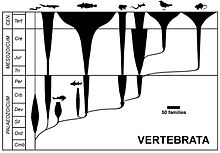

Vertebrates originated during the

From fish to amphibians

The first

Mesozoic vertebrates

After the Mesozoic

The Cenozoic world saw great diversification of bony fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.[40][41]

Over half of all living vertebrate species (about 32,000 species) are fish (non-tetrapod craniates), a diverse set of lineages that inhabit all the world's aquatic ecosystems, from snow minnows (Cypriniformes) in Himalayan lakes at elevations over 4,600 metres (15,100 feet) to flatfishes (order Pleuronectiformes) in the Challenger Deep, the deepest ocean trench at about 11,000 metres (36,000 feet). Many fish varieties are the main predators in most of the world's freshwater and marine water bodies . The rest of the vertebrate species are tetrapods, a single lineage that includes amphibians (with roughly 7,000 species); mammals (with approximately 5,500 species); and reptiles and birds (with about 20,000 species divided evenly between the two classes). Tetrapods comprise the dominant megafauna of most terrestrial environments and also include many partially or fully aquatic groups (e.g., sea

Classification

There are several ways of classifying animals.

Traditional classification

Conventional classification has living vertebrates grouped into seven classes based on traditional interpretations of gross

- Subphylum Vertebrata

- Class Agnatha (jawless fishes)

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes)

- Class Osteichthyes (bony fishes)

- Class Amphibia(amphibians)

- Class Reptilia(reptiles)

- Class Aves(birds)

- Class Mammalia(mammals)

In addition to these, there are two classes of extinct armoured fishes, the

Other ways of classifying the vertebrates have been devised, particularly with emphasis on the

- Subphylum Vertebrata

- †Palaeospondylus

- Infraphylum Agnatha or Cephalaspidomorphi (lampreys and other jawless fishes)

- Superclass †Anaspidomorphi (anaspids and relatives)

- Infraphylum Gnathostomata (vertebrates with jaws)

- Class †Placodermi(extinct armoured fishes)

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes)

- Class †Acanthodii (extinct spiny "sharks")

- Superclass Osteichthyes (bony vertebrates)

- Class Actinopterygii (ray-finned bony fishes)

- Class Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fishes, including the tetrapods)

- Superclass Tetrapoda(four-limbed vertebrates)

- Class Amphibia (amphibians, some ancestral to the amniotes)—now a paraphyletic group

- Class Synapsida (mammals and the extinct mammal-like reptiles)

- Class Sauropsida (reptiles and birds)

- Class

- Class †

While this traditional classification is orderly, most of the groups are

Phylogenetic relationships

In

| Vertebrata/ |

|

†" Placodermi " | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Craniata |

Note that, as shown in the cladogram above, the †"

Also note that

Tetrapoda

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| four‑limbed vertebrates |

Note that

The placement of hagfish on the vertebrate tree of life has been controversial. Their lack of proper

| |||||||||||||

Number of extant species

The number of described vertebrate species are split between

| Vertebrate groups | Image | Class | Estimated number of described species[54][55] |

Group totals[54] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

amniotic membrane so need to reproduce in water |

Jawless

|

Fish |

|

Myxini )

(hagfish |

78 | >32,900 |

|

Hyperoartia )

(lamprey |

40 | ||||

Jawed

|

|

cartilaginous

fish |

>1,100 | |||

|

ray-finned

fish |

>32,000 | ||||

|

lobe-finned

fish |

8 | ||||

| Tetrapods |

|

amphibians | 7,302 | 33,278 | ||

amniotic membrane adapted to reproducing on land |

|

reptiles | 10,711 | |||

|

mammals | 5,513 | ||||

|

birds | 10,425 | ||||

| Total described species | 66,178 | |||||

The IUCN estimates that 1,305,075 extant invertebrate species have been described,[54] which means that less than 5% of the described animal species in the world are vertebrates.

Vertebrate species databases

The following databases maintain (more or less) up-to-date lists of vertebrate species:

- Fish: Fishbase

- Amphibians: Amphibiaweb

- Reptiles: Reptile Database

- Birds: Avibase

- Mammals: Mammal species of the World

Reproductive systems

Nearly all vertebrates undergo

Inbreeding

During sexual reproduction, mating with a close relative (inbreeding) often leads to inbreeding depression. Inbreeding depression is considered to be largely due to expression of deleterious recessive mutations.[56] The effects of inbreeding have been studied in many vertebrate species.

In several species of fish, inbreeding was found to decrease reproductive success.[57][58][59]

Inbreeding was observed to increase juvenile mortality in 11 small animal species.[60]

A common breeding practice for pet dogs is mating between close relatives (e.g. between half- and full siblings).[61] This practice generally has a negative effect on measures of reproductive success, including decreased litter size and puppy survival.[62][63][64]

Incestuous matings in birds result in severe fitness costs due to inbreeding depression (e.g. reduction in hatchability of eggs and reduced progeny survival).[65][66][67]

Inbreeding avoidance

As a result of the negative fitness consequences of inbreeding, vertebrate species have evolved mechanisms to avoid inbreeding.

Numerous inbreeding avoidance mechanisms operating prior to mating have been described. Toads and many other amphibians display

When female sand lizards mate with two or more males, sperm competition within the female's reproductive tract may occur. Active selection of sperm by females appears to occur in a manner that enhances female fitness.[70] On the basis of this selective process, the sperm of males that are more distantly related to the female are preferentially used for fertilization, rather than the sperm of close relatives.[70] This preference may enhance the fitness of progeny by reducing inbreeding depression.

Outcrossing

Mating with unrelated or distantly related members of the same species is generally thought to provide the advantage of masking deleterious recessive mutations in progeny[71] (see heterosis). Vertebrates have evolved numerous diverse mechanisms for avoiding close inbreeding and promoting outcrossing[72] (see inbreeding avoidance).

Outcrossing as a way of avoiding inbreeding depression has been especially well studied in birds. For instance, inbreeding depression occurs in the great tit (Parus major) when the offspring are produced as a result of a mating between close relatives. In natural populations of the great tit, inbreeding is avoided by dispersal of individuals from their birthplace, which reduces the chance of mating with a close relative.[73]

Purple-crowned fairywren females paired with related males may undertake extra-pair matings that can reduce the negative effects of inbreeding, despite ecological and demographic constraints.[67]

Southern pied babblers (Turdoides bicolor) appear to avoid inbreeding in two ways: through dispersal and by avoiding familiar group members as mates.[74] Although both genders disperse locally, they move outside the range where genetically related individuals are likely to be encountered. Within their group, individuals only acquire breeding positions when the opposite-sex breeder is unrelated.

Cooperative breeding in birds typically occurs when offspring, usually males, delay dispersal from their natal group in order to remain with the family to help rear younger kin.[75] Female offspring rarely stay at home, dispersing over distances that allow them to breed independently or to join unrelated groups.

Parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis is a natural form of reproduction in which growth and development of embryos occur without fertilization.

Reproduction in

Self-fertilization

Two

Population trends

The

See also

- Marine vertebrate – Marine animals with a vertebrate column

- Invertebrate

- Exoskeleton

- Skeletal system of the horse – The skeletal system is made of many interconnected tissues including bone, cartilage, and tendons

- Taxonomy of the vertebrates (Young, 1962) – Classification of spine-possessing animals according to some authorities

Notes

- cladistically included within Sarcopterygii.[6]

References

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ S2CID 83266247.

- ^ "vertebrate". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Vertebrata". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "Table 1a: Number of species evaluated in relation to the overall number of described species, and numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms". IUCN Red List. 18 July 2019.

- .

- PMID 21712821.

- S2CID 5613153.

- PMID 1496398.

- PMID 19741680.

- ^ "vertebrate". Online Etymology Dictionary. Dictionary.com.

- ^ "vertebra". Online Etymology Dictionary. Dictionary.com.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben. "Vertebrates: More on Morphology". UCMP. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Romer, A.S. (1949): The Vertebrate Body. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970)

- ISBN 978-0-03-022369-3.

- ISBN 978-3-11-010661-9.

- hdl:10044/1/107350.

- S2CID 85231736.

- ^ Clack, J. A. (2002): Gaining ground: the origin and evolution of tetrapods. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana. 369 pp

- PMID 17076284.

- S2CID 39290007.

- PMID 22230617.

- ^ Dupin, E.; Creuzet, S.; Le Douarin, N.M. (2007) "The Contribution of the Neural Crest to the Vertebrate Body". In: Jean-Pierre Saint-Jeannet, Neural Crest Induction and Differentiation, pp. 96–119, Springer Science & Business Media.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, M.; Gonslow, G. (2001): Analysis of Vertebrate Structure. 5th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York

- ^ "Keeping an eye on evolution". PhysOrg.com. 3 December 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ "Hyperotreti". tolweb.org.

- ^ PMID 26419477.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- S2CID 4397099.

- ^ S2CID 4402854.

- doi:10.1360/03wd0026.

- S2CID 24895681.

- ^ Waggoner, B. "Vertebrates: Fossil Record". UCMP. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ Tim Haines, T.; Chambers, P. (2005). The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Firefly Books.

- S2CID 22803015.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 17. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1954. p. 107.

- ISBN 978-0-534-49276-2.

- ISBN 9783540224211.

- PMC 6170748 – via Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- .

- ISBN 978-87-88757-78-1.

- ^ Hildebran, M.; Gonslow, G. (2001): Analysis of Vertebrate Structure. 5th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York, page 33: Comment: The problem of naming sister groups

- ^ ISBN 978-0632056378. Archived from the originalon 19 October 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2006.

- PMID 30607258.

- ^ Janvier, P. 1997. Vertebrata. Animals with backbones. Version 1 January 1997 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Vertebrata/14829/1997.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

- PMID 29653534.

- S2CID 59423401.

- S2CID 45922669.

- S2CID 4462506.

- PMID 25581798.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-4449-0.

- PMID 30670644.

- ^ IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2014.3. Summary Statistics for Globally Threatened Species. Table 1: Numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms (1996–2014).

- ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- S2CID 771357.

- PMID 16189545.

- S2CID 44317000.

- PMID 23798977.

- PMID 7043080.

- PMID 21737321.

- PMID 10490080.

- PMID 15803761.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- S2CID 16206523.

- PMID 22643890.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ PMID 21238151.

- PMID 3898363.

- PMID 21237809.

- PMID 18211876.

- PMID 22471769.

- S2CID 205476732.

- PMID 22977071.

- PMID 21868391.

- PMID 17546077.

- S2CID 2015354.

- PMID 26865699.

- PMID 19706532.

- S2CID 9474211.

- ^ PMID 23112206.

- PMID 22990587.

- ^ "Living Planet Report 2018 | WWF". wwf.panda.org. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-940529-90-2. Archived(PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "WWF Finds Human Activity Is Decimating Wildlife Populations". Time. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- .

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-697-28654-3.

- "Vertebrata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

External links

- Tree of Life

- Tunicates and not cephalochordates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates

- Vertebrate Pests chapter in United States Environmental Protection Agency and University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences National Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual

- The Vertebrates

- The Origin of Vertebrates Marc W. Kirschner, iBioSeminars, 2008.