Sexual dimorphism

| Part of a series on |

| Sex |

|---|

|

| Biological terms |

| Sexual reproduction |

|

| Sexuality |

| Sexual system |

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction.[1] The condition occurs in most dioecious species, which consist of most animals and some plants. Differences may include secondary sex characteristics, size, weight, color, markings, or behavioral or cognitive traits. Male-male reproductive competition has evolved a diverse array of sexually dimorphic traits. Aggressive utility traits such as "battle" teeth and blunt heads reinforced as battering rams are used as weapons in aggressive interactions between rivals. Passive displays such as ornamental feathering or song-calling have also evolved mainly through sexual selection.[2] These differences may be subtle or exaggerated and may be subjected to sexual selection and natural selection. The opposite of dimorphism is monomorphism, when both biological sexes are phenotypically indistinguishable from each other.[3]

Overview

Ornamentation and coloration

Common and easily identified types of dimorphism consist of ornamentation and coloration, though not always apparent. A difference in the coloration of sexes within a given species is called sexual dichromatism, commonly seen in many species of birds and reptiles.[4] Sexual selection leads to exaggerated dimorphic traits that are used predominantly in competition over mates.[5] The increased fitness resulting from ornamentation offsets its cost to produce or maintain, suggesting complex evolutionary implications, but the costs and evolutionary implications vary from species to species.[6]

The

Another example of sexual dichromatism is that of nestling

Frogs constitute another conspicuous illustration of the principle. There are two types of dichromatism for frog species: ontogenetic and dynamic. Ontogenetic frogs are more common and have permanent color changes in males or females.

Females often show a preference for exaggerated male

Similar sexual dimorphism and mating choice are also observed in many fish species. For example, male guppies have colorful spots and ornamentations, while females are generally grey. Female guppies prefer brightly colored males to duller males.[19][page needed]

In redlip blennies, only the male fish develops an organ at the anal-urogenital region that produces antimicrobial substances. During parental care, males rub their anal-urogenital regions over their nests' internal surfaces, thereby protecting their eggs from microbial infections, one of the most common causes for mortality in young fish.[20]

In Australian ambrosia beetles, males are seen to have smaller bodies then females. This is interesting, for this is a reversal in the trends seen in sixual dimorphism. Females are seen to have larger bodies since they guard the colonies they live in.

Plants

Most

Males and females in

Various other dioecious exceptions, such as

Some plants, such as some species of

Females of the aquatic plant

Sexual dimorphism in plants can also be dependent on reproductive development. This can be seen in Cannabis sativa, a type of hemp, which have higher photosynthesis rates in males while growing but higher rates in females once the plants become sexually mature.[27]

Every sexually reproducing extant species of the vascular plant has an alternation of generations; the plants we see about us generally are

Insects

Insects display a wide variety of sexual dimorphism between taxa including size, ornamentation and coloration.

In some species, there is evidence of male dimorphism, but it appears to be for distinctions of roles. This is seen in the bee species Macrotera portalis in which there is a small-headed morph, capable of flight, and large-headed morph, incapable of flight, for males.[33] Anthidium manicatum also displays male-biased sexual dimorphism. The selection for larger size in males rather than females in this species may have resulted due to their aggressive territorial behavior and subsequent differential mating success.[34] Another example is Lasioglossum hemichalceum, which is a species of sweat bee that shows drastic physical dimorphisms between male offspring.[35] Not all dimorphism has to have a drastic difference between the sexes. Andrena agilissima is a mining bee where the females only have a slightly larger head than the males.[36]

Weaponry leads to increased fitness by increasing success in male–male competition in many insect species.[37] The beetle horns in Onthophagus taurus are enlarged growths of the head or thorax expressed only in the males. Copris ochus also has distinct sexual and male dimorphism in head horns.[38] Another beetle with a distinct horn-related sexual dimorphism is Allomyrina dichotoma, also known as the Japanese rhinoceros beetle.[39] These structures are impressive because of the exaggerated sizes.[40] There is a direct correlation between male horn lengths and body size and higher access to mates and fitness.[40] In other beetle species, both males and females may have ornamentation such as horns.[38] Generally, insect sexual size dimorphism (SSD) within species increases with body size.[41]

Sexual dimorphism within insects is also displayed by dichromatism. In butterfly genera Bicyclus and Junonia, dimorphic wing patterns evolved due to sex-limited expression, which mediates the intralocus sexual conflict and leads to increased fitness in males.[42] The sexual dichromatic nature of Bicyclus anynana is reflected by female selection on the basis of dorsal UV-reflective eyespot pupils.[43] The common brimstone also displays sexual dichromatism; males have yellow and iridescent wings, while female wings are white and non-iridescent.[44] Naturally selected deviation in protective female coloration is displayed in mimetic butterflies.[45]

Spiders and sexual cannibalism

Many

Fish

Ray-finned fish are an ancient and diverse class, with the widest degree of sexual dimorphism of any animal class. Fairbairn notes that "females are generally larger than males but males are often larger in species with male–male combat or male paternal care ... [sizes range] from dwarf males to males more than 12 times heavier than females."[52][page needed]

There are cases where males are substantially larger than females. An example is Lamprologus callipterus, a type of cichlid fish. In this fish, the males are characterized as being up to 60 times larger than the females. The male's increased size is believed to be advantageous because males collect and defend empty snail shells in each of which a female breeds.[53] Males must be larger and more powerful in order to collect the largest shells. The female's body size must remain small because in order for her to breed, she must lay her eggs inside the empty shells. If she grows too large, she will not fit in the shells and will be unable to breed. The female's small body size is also likely beneficial to her chances of finding an unoccupied shell. Larger shells, although preferred by females, are often limited in availability.[54] Hence, the female is limited to the growth of the size of the shell and may actually change her growth rate according to shell size availability.[55] In other words, the male's ability to collect large shells depends on his size. The larger the male, the larger the shells he is able to collect. This then allows for females to be larger in his brooding nest which makes the difference between the sizes of the sexes less substantial. Male–male competition in this fish species also selects for large size in males. There is aggressive competition by males over territory and access to larger shells. Large males win fights and steal shells from competitors. Another example is the dragonet, in which males are considerably larger than females and possess longer fins.

Sexual dimorphism also occurs in hermaphroditic fish. These species are known as

Social organization plays a large role in the changing of sex by the fish. It is often seen that a fish will change its sex when there is a lack of a dominant male within the social hierarchy. The females that change sex are often those who attain and preserve an initial size advantage early in life. In either case, females which change sex to males are larger and often prove to be a good example of dimorphism.

In other cases with fish, males will go through noticeable changes in body size, and females will go through morphological changes that can only be seen inside of the body. For example, in sockeye salmon, males develop larger body size at maturity, including an increase in body depth, hump height, and snout length. Females experience minor changes in snout length, but the most noticeable difference is the huge increase in gonad size, which accounts for about 25% of body mass.[59]

Sexual selection was observed for female ornamentation in

Amphibians and non-avian reptiles

In amphibians and reptiles, the degree of sexual dimorphism varies widely among

Male painted dragon lizards, Ctenophorus pictus. are brightly conspicuous in their breeding coloration, but male colour declines with aging. Male coloration appears to reflect innate anti-oxidation capacity that protects against oxidative DNA damage.[65] Male breeding coloration is likely an indicator to females of the underlying level of oxidative DNA damage (a significant component of aging) in potential mates.[65]

Birds

Avian dinosaurs

Possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain macroevolution of sexual size dimorphism in birds. These include sexual selection, selection for fecundity in females, niche divergence between the sexes, and allometry, but their relative importance is still not fully understood .

Sexual dimorphism is a product of both genetics and environmental factors. An example of

Migratory patterns and behaviors also influence sexual dimorphisms. This aspect also stems back to size dimorphism in species. It has been shown that the larger males are better at coping with the difficulties of migration and thus are more successful in reproducing when reaching the breeding destination.[74] When viewing this from an evolutionary standpoint, many theories and explanations come into consideration. If these are the result for every migration and breeding season, the expected results should be a shift towards a larger male population through sexual selection. Sexual selection is strong when the factor of environmental selection is also introduced. Environmental selection may support a smaller chick size if those chicks were born in an area that allowed them to grow to a larger size, even though under normal conditions they would not be able to reach this optimal size for migration. When the environment gives advantages and disadvantages of this sort, the strength of selection is weakened and the environmental forces are given greater morphological weight. The sexual dimorphism could also produce a change in timing of migration leading to differences in mating success within the bird population.[75] When the dimorphism produces that large of a variation between the sexes and between the members of the sexes, multiple evolutionary effects can take place. This timing could even lead to a speciation phenomenon if the variation becomes strongly drastic and favorable towards two different outcomes. Sexual dimorphism is maintained by the counteracting pressures of natural selection and sexual selection. For example, sexual dimorphism in coloration increases the vulnerability of bird species to predation by European sparrowhawks in Denmark.[76] Presumably, increased sexual dimorphism means males are brighter and more conspicuous, leading to increased predation.[76] Moreover, the production of more exaggerated ornaments in males may come at the cost of suppressed immune function.[72] So long as the reproductive benefits of the trait due to sexual selection are greater than the costs imposed by natural selection, then the trait will propagate throughout the population. Reproductive benefits arise in the form of a larger number of offspring, while natural selection imposes costs in the form of reduced survival. This means that even if the trait causes males to die earlier, the trait is still beneficial so long as males with the trait produce more offspring than males lacking the trait. This balance keeps dimorphism alive in these species and ensures that the next generation of successful males will also display these traits that are attractive to females.

Such differences in form and reproductive roles often cause differences in behavior. As previously stated, males and females often have different roles in reproduction. The courtship and mating behavior of males and females are regulated largely by hormones throughout a bird's lifetime.[77] Activational hormones occur during puberty and adulthood and serve to 'activate' certain behaviors when appropriate, such as territoriality during breeding season.[77] Organizational hormones occur only during a critical period early in development, either just before or just after hatching in most birds, and determine patterns of behavior for the rest of the bird's life.[77] Such behavioral differences can cause disproportionate sensitivities to anthropogenic pressures.[78] Females of the whinchat in Switzerland breed in intensely managed grasslands.[78] Earlier harvesting of the grasses during the breeding season lead to more female deaths.[78] Populations of many birds are often male-skewed and when sexual differences in behavior increase this ratio, populations decline at a more rapid rate.[78] Also not all male dimorphic traits are due to hormones like testosterone, instead they are a naturally occurring part of development, for example plumage.[79] In addition, the strong hormonal influence on phenotypic differences suggests that the genetic mechanism and genetic basis of these sexually dimorphic traits may involve transcription factors or cofactors rather than regulatory sequences.[80]

Sexual dimorphism may also influence differences in parental investment during times of food scarcity. For example, in the blue-footed booby, the female chicks grow faster than the males, resulting in booby parents producing the smaller sex, the males, during times of food shortage. This then results in the maximization of parental lifetime reproductive success.[81] In Black-tailed Godwits Limosa limosa limosa females are also the larger sex, and the growth rates of female chicks are more susceptible to limited environmental conditions.[82]

Sexual dimorphism may also only appear during mating season; some species of birds only show dimorphic traits in seasonal variation. The males of these species will molt into a less bright or less exaggerated color during the off-breeding season.[80] This occurs because the species is more focused on survival than on reproduction, causing a shift into a less ornate state. [dubious ]

Consequently, sexual dimorphism has important ramifications for conservation. However, sexual dimorphism is not only found in birds and is thus important to the conservation of many animals. Such differences in form and behavior can lead to sexual segregation, defined as sex differences in space and resource use.[83] Most sexual segregation research has been done on ungulates,[83] but such research extends to bats,[84] kangaroos,[85] and birds.[86] Sex-specific conservation plans have even been suggested for species with pronounced sexual segregation.[84]

The term sesquimorphism (the Latin numeral prefix sesqui- means one-and-one-half, so halfway between mono- (one) and di- (two)) has been proposed for bird species in which "both sexes have basically the same plumage pattern, though the female is clearly distinguishable by reason of her paler or washed-out colour".[87]: 14 Examples include Cape sparrow (Passer melanurus),[87]: 67 rufous sparrow (subspecies P. motinensis motinensis),[87]: 80 and saxaul sparrow (P. ammodendri).[87]: 245

Non-avian dinosaurs

Sexual dimorphism is thought to have been present in non-avian dinosaurs.

Mammals

In a large proportion of mammal species, males are larger than females. Both

Pinnipeds

Primates

Humans

| |

|

|

|

Top: Stylised illustration of humans on the Pioneer plaque, showing both male (left) and female (right).

| |

According to Clark Spencer Larsen, modern day

The average basal metabolic rate is about 6 percent higher in adolescent males than females and increases to about 10 percent higher after puberty. Females tend to convert more food into fat, while males convert more into muscle and expendable circulating energy reserves. According to Tim Hewett, director of research in the department of sports medicine at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, females have, on average, 50–60% of the upper body strength of males, and 80-90% of the lower body strength of males, relative to body size, but females have higher endurance than males.[97]

The difference in strength relative to body mass is less pronounced in trained individuals. In Olympic weightlifting, male records vary from 5.5× body mass in the lowest weight category to 4.2× in the highest weight category, while female records vary from 4.4× to 3.8×, a weight-adjusted difference of only 10–20%, and an absolute difference of about 30% (i.e., 492 kg vs 348 kg for unlimited weight classes; see Olympic weightlifting records). A study, carried out by analyzing annual world rankings from 1980 to 1996, found that males' running times were, on average, 10% faster than females'.[98]

In early adolescence, females are on average taller than males (as females tend to go through puberty earlier), but males, on average, surpass them in height in later adolescence and adulthood. In the United States, adult males are on average 9% taller[99] and 16.5% heavier[100] than adult females.

Males typically have larger

Females typically have more white blood cells (stored and circulating), as well as more granulocytes and B and T lymphocytes. Additionally, they produce more antibodies at a faster rate than males, hence they develop fewer infectious diseases and succumb for shorter periods.[101] Ethologists argue that females, interacting with other females and multiple offspring in social groups, have experienced such traits as a selective advantage.[103][104][105][106][107][excessive citations] Females have a higher sensitivity to pain due to aforementioned nerve differences that increase the sensation, and females thus require higher levels of pain medication after injury.[102] Hormonal changes in females affect pain sensitivity, and pregnant women have the same sensitivity as males. Acute pain tolerance is also more consistent over a lifetime in females than males, despite these hormonal changes.[108] Despite differences in physical feeling, both sexes have similar psychological tolerance to (or ability to cope with and ignore) pain.[109]

In the

The relationship between sex differences in the brain and human behavior is a subject of controversy in psychology and society at large.

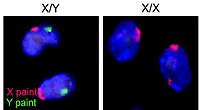

Sexual dimorphism was also described in the gene level and shown to extend from the sex chromosomes. Overall, about 6500 genes have been found to have sex-differential expression in at least one tissue. Many of these genes are not directly associated with reproduction, but rather linked to more general biological features. In addition, it has been shown that genes with sex-specific expression undergo reduced selection efficiency, which leads to higher population frequencies of deleterious mutations and contributes to the prevalence of several human diseases.[122][123]

Immune function

Sexual dimorphism in immune function is a common pattern in vertebrates and also in a number of invertebrates. Most often, females are more 'immunocompetent' than males. This trait is not consistent among all animals, but differs depending on taxonomy, with the most female-biased immune systems being found in insects.[124] In mammals this results in more frequent and severe infections in males and higher rates of autoimmune disorders in females. One potential cause may be differences in gene expression of immune cells between the sexes.[125] Another explanation is that endocrinological differences between the sexes impact the immune system – for example, testosterone acts as an immunosuppressive agent.[126]

Cells

Phenotypic differences between sexes are evident even in

Reproductively advantageous

In theory, larger females are favored by competition for mates, especially in polygamous species. Larger females offer an advantage in fertility, since the physiological demands of reproduction are limiting in females. Hence there is a theoretical expectation that females tend to be larger in species that are monogamous. Females are larger in many species of insects, many spiders, many fish, many reptiles, owls, birds of prey and certain mammals such as the spotted hyena, and baleen whales such as blue whale. As an example, in some species, females are sedentary, and so males must search for them. Fritz Vollrath and Geoff Parker argue that this difference in behaviour leads to radically different selection pressures on the two sexes, evidently favouring smaller males.[131] Cases where the male is larger than the female have been studied as well,[131] and require alternative explanations.

One example of this type of sexual size dimorphism is the bat

Some species of anglerfish also display extreme sexual dimorphism. Females are more typical in appearance to other fish, whereas males are tiny rudimentary creatures with stunted digestive systems. A male must find a female and fuse with her: he then lives parasitically, becoming little more than a sperm-producing body in what amounts to an effectively hermaphrodite composite organism. A similar situation is found in the Zeus water bug Phoreticovelia disparata where the female has a glandular area on her back that can serve to feed a male, which clings to her (although males can survive away from females, they generally are not free-living).[134] This is taken to the logical extreme in the Rhizocephala crustaceans, like the Sacculina, where the male injects itself into the female's body and becomes nothing more than sperm producing cells, to the point that the superorder used to be mistaken for hermaphroditic.[135]

Some plant species also exhibit dimorphism in which the females are significantly larger than the males, such as in the moss Dicranum[136] and the liverwort Sphaerocarpos.[137] There is some evidence that, in these genera, the dimorphism may be tied to a sex chromosome,[137][138] or to chemical signalling from females.[139]

Another complicated example of sexual dimorphism is in Vespula squamosa, the southern yellowjacket. In this wasp species, the female workers are the smallest, the male workers are slightly larger, and the female queens are significantly larger than her female workers and male counterparts.[citation needed]

Evolution

In 1871,

The first step towards sexual dimorphism is the size differentiation of sperm and eggs (anisogamy).[142][143][144][145]: 917 Anisogamy and the usually large number of small male gametes relative to the larger female gametes usually lies in the development of strong sperm competition,[146][147] because small sperm enable organisms to produce a large number of sperm, and make males (or male function of hermaphrodites[148]) more redundant.

This intensifies male competition for mates and promotes the evolution of other sexual dimorphism in many species, especially in

Volvocine algae have been useful in understanding the evolution of sexual dimorphism [149] and species like the beetle C. maculatus, where the females are larger than the males, are used to study its underlying genetic mechanisms. [150]

In many non-monogamous species, the benefit to a male's reproductive fitness of mating with multiple females is large, whereas the benefit to a female's reproductive fitness of mating with multiple males is small or nonexistent.

These traits could be ones that allow him to fight off other males for control of territory or a

Females may choose males that appear strong and healthy, thus likely to possess "good alleles" and give rise to healthy offspring.[155] In some species, however, females seem to choose males with traits that do not improve offspring survival rates, and even traits that reduce it (potentially leading to traits like the peacock's tail).[154] Two hypotheses for explaining this fact are the sexy son hypothesis and the handicap principle.

The sexy son hypothesis states that females may initially choose a trait because it improves the survival of their young, but once this preference has become widespread, females must continue to choose the trait, even if it becomes harmful. Those that do not will have sons that are unattractive to most females (since the preference is widespread) and so receive few matings.[156]

The handicap principle states that a male who survives despite possessing some sort of handicap thus proves that the rest of his genes are "good alleles". If males with "bad alleles" could not survive the handicap, females may evolve to choose males with this sort of handicap; the trait is acting as a hard-to-fake signal of fitness.[157]

See also

- Bateman's principle

- List of homologues of the human reproductive system

- Sex differences in humans

- Sex differences in human psychology

- Sexual differentiation

- Sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs

- Sexual dimorphism in non-human primates

- Sexual dimorphism measures

- Sexually dimorphic nucleus

- Gynandromorphism

References

- ISBN 978-0-12-813252-4.

- ISBN 9780123735539.

- ^ "Dictionary of Human Evolution and Biology". Human-biology.key-spot.ru. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- PMID 18626076.

- ^ Andersson 1994, p. 8

- PMID 1195756.

- ^ PMID 14557541.

- ^ "Birds-of-Paradise: Beauty Kings". National Geographic Society. 19 October 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- .

- PMID 9578901.

- PMID 9578901.

- PMID 11839194.

- PMID 12816639.

- JSTOR 3545643.

- ^ Donnellan, S. C., & Mahony, M. J. (2004). Allozyme, chromosomal, and morphological variability in the Litoria lesueuri species group (Anura : Hylidae), including a description of a new species. Australian Journal of Zoology

- ^ Bell, R. C., & Zamudio, K. R. (2012). Sexual dichromatism in frogs: natural selection, sexual selection, and unexpected diversity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

- PMID 28568715.

- .

- ISBN 9780521448789. Retrieved 3 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- PMID 17148395.

- JSTOR 2445418.

- ISBN 978-3-642-79844-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4822-0133-8.

- S2CID 31296391.

- ^ "Eel Grass (aka wild celery, tape grass)". University of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011.

- PMID 19218583.

- ISBN 978-3-540-64597-9. p. 206

- S2CID 17439073.

- PMID 21874083.

- S2CID 22935710.

- ^ "hackberry emperor – Asterocampa celtis (Boisduval & Leconte)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- .

- S2CID 37651908.

- ^ Jaycox Elbert R (1967). "Territorial Behavior Among Males of Anthidium Bamngense". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 40 (4): 565–570.

- JSTOR 25085712.

- ISSN 0394-9370.

- ^ Wang MQ, Yang D (2005). "Sexual dimorphism in insects". Chinese Bulletin of Entomology. 42: 721–725.

- ^ S2CID 34705415.

- ISSN 1432-0762.

- ^ S2CID 221736269.

- ^ Teder, T., & Tammaru, T. (2005). "Sexual size dimorphism within species increases with body size in insects". Oikos [ISBN missing]

- PMID 21123259.

- PMID 16048768.

- JSTOR 3546246.

- PMID 18426753.

- PMID 30416880.

- ^ Smith T. Discovering the daily activity pattern of Zygiella x-notata and its relationship to light (PDF) (MS thesis).

- PMID 28565440.

- ^ S2CID 54373571.

- ^ Foellmer MW, Fairbairn DJ (2004). "Males under attack: Sexual cannibalism and its consequences for male morphology and behaviour in an orb-weaving spider". Evolutionary Ecology Research. 6: 163–181.

- PMID 26631566.

- ISBN 978-0691141961.

- S2CID 12396902.

- S2CID 53192909.

- S2CID 26712792. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- PMID 20485547.

- PMID 21227182.

- .

- .

- ^ PMID 11606720.

- ^ .

- S2CID 7887284.

- PMID 24741020.

- ^ a b Pinto, A., Wiederhecker, H., & Colli, G. (2005). Sexual dimorphism in the Neotropical lizard, Tropidurus torquatus (Squamata, Tropiduridae). Amphibia-Reptilia.

- ^ S2CID 205783815.

- .

- PMID 38462717.

- ^ Andersson 1994, p. 269

- S2CID 276492.

- PMID 11818247. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 August 2005.

- PMID 17754986.

- ^ S2CID 15799876.

- S2CID 4316752.

- .

- S2CID 13830052.

- ^ S2CID 36836956.

- ^ S2CID 13868097.

- ^ .

- ^ Owens, I. P. F., Short, R.V.,. (1995). Hormonal basis of sexual dimorphism in birds: Implications for new theories of sexual selection. Trends in Ecology & Evolution., 10(REF), 44.

- ^ S2CID 11490688.

- .

- S2CID 90880117.

- ^ PMID 18459333.

- ^ .

- doi:10.1071/ZO05062.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85661-048-6.

- S2CID 7419814.

- S2CID 208557639.

- .

- S2CID 91796880.

- S2CID 25307359.

- hdl:11336/29893.

- PMID 12886010.

- . 39 (3): 502–512.

- ISBN 978-0-19-510357-1.

- ^ Rettner, Rachel (3 January 2014). "Why Pull-Ups Are Harder for Women". LiveScience.

- PMID 9861606.

- ^ "National Health Statistics Reports" (PDF). National Health Statistics Reports. 10. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002" (PDF). Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ OCLC 7831448.

- ^ S2CID 85527866.

- ISBN 978-0-87795-484-2.

- )

- ISBN 978-0-316-81236-8.

- ^ McLaughlin M, Shryer T (8 August 1988). "Men vs women: the new debate over sex differences". U.S. News & World Report: 50–58.

- PMID 6259728.

- ^ "Acute Pain Tolerance Is More Consistent Over Time in Women Than Men, According to New Research". NCCIH. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Woznicki K. "Pain Tolerance and Sensitivity in Men, Women, Redheads, and More". WebMD. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- S2CID 19323646.

- PMID 22238103.

- ^ "Diverse Roles for Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin in Reproduction". biolreprod.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-393-06838-2.

- ISBN 978-0-674-05730-2.

- S2CID 35293796.

- PMID 10234034.

- PMID 18440950.

- PMID 12488829.

- S2CID 4127512. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 May 2010.

- PMID 26132764.

- S2CID 4028467.

- PMID 28173793.

- PMID 25014762.

- PMID 30288910.

- PMID 31541153.

- PMID 2696846.

- S2CID 4318641.

- PMID 17420291.

- PMID 21852955.

- PMID 19190082.

- ^ S2CID 4320130.

- PMID 19197511.

- JSTOR 1382823.

- S2CID 4382038. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 September 2004.

- ^ Mechanism of Fertilization: Plants to Humans, edited by Brian Dale

- ISBN 978-0-521-66097-6.

- ^ a b Schuster RM (1984). "Comparative Anatomy and Morphology of the Hepaticae". New Manual of Bryology. Vol. 2. Nichinan, Miyazaki, Japan: The Hattori botanical Laboratory. p. 891.

- ISBN 978-0-231-04516-2.

- JSTOR 2430169.

- S2CID 129620469.

- ISSN 1631-0683.

- PMID 22869736.

- PMID 30125231.

- PMID 38306281.

- ISBN 978-0-08-092090-0.

- S2CID 29879237.

- PMID 20097207.

- S2CID 84275261.

- PMID 25003332.

- S2CID 237242736.

- ^ Futuyma 2005, p. 330

- ^ Futuyma 2005, p. 331

- ^ Futuyma 2005, p. 332

- ^ a b Ridley 2004, p. 328

- ^ Futuyma 2005, p. 335

- ^ Ridley 2004, p. 330

- ^ Ridley 2004, p. 332

Sources

- Andersson MB (1994). Sexual Selection. ISBN 978-0-691-00057-2.

- Futuyma D (2005). Evolution (1st ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-187-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-0345-9.

Further reading

- Bonduriansky R (January 2007). "The evolution of condition-dependent sexual dimorphism". The American Naturalist. 169 (1): 9–19. S2CID 17439073.

- Figuerola J (1999). "A comparative study on the evolution of reversed size dimorphism in monogamous waders". S2CID 85330510.

- Székely T, Lislevand T, Figuerola J, Fairbairn D, Blanckenhorn W (2007). Sex, Size, and Gender Roles: Evolutionary Studies of Sexual Size Dimorphism. pp. 16–26.

External links

- Sex+dimorphism at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)