Hirudo medicinalis

This article needs to be updated. (September 2021) |

| Hirudo medicinalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Clade: | Pleistoannelida |

| Clade: | Sedentaria |

| Class: | Clitellata |

| Subclass: | Hirudinea |

| Order: | Arhynchobdellida |

| Family: | Hirudinidae |

| Genus: | Hirudo |

| Species: | H. medicinalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hirudo medicinalis | |

Hirudo medicinalis, or the European medicinal leech, is one of several

Other species of Hirudo sometimes also used as medicinal leeches include H. orientalis, H. troctina, and H. verbana. The Asian medicinal leech includes Hirudinaria manillensis, and the North American medicinal leech is Macrobdella decora.

Medicinal leech populations were reduced significantly in many countries during the 19th century due to the high demand in medical contexts, and remain endangered in many countries today.[3]

Morphology

The general

Medicinal leeches are hermaphrodites that reproduce by sexual mating, laying eggs in clutches of up to 50 near (but not under) water, and in shaded, humid places. A study done in Poland found that medicinal leeches sometimes breed inside the nests of large aquatic birds, noting that conservation efforts directed at bird habitats may also indirectly help preserve dwindling leech populations.[7]

Range and ecology

Their range extends over almost the whole of Europe and into Asia as far as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The preferred habitat for this species is muddy freshwater pools and ditches with plentiful weed growth in temperate climates.

Medical use

Beneficial secretions

Medicinal leeches have been found to secrete

Historically

The first recorded use of leech therapy was 3,500 years ago in Ancient Egypt.

Medical use of leeches was discussed by Avicenna in The Canon of Medicine (1020s), and by Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi in the 12th century.[citation needed]

These sources indicated leech therapy for a wide variety of ailments, including edema,.[12] "blood stasis",[13] and skin diseases.[14]

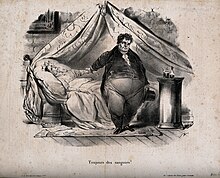

In medieval and early modern European medicine, the medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis and its congeners H. verbana, H. troctina, and H. orientalis) was used to remove blood from a patient as part of a process to balance the

Manchester Royal Infirmary used 50,000 leeches a year in 1831. The price of leeches varied between one penny and threepence halfpenny each. In 1832 leeches accounted for 4.4% of the total hospital expenditure. The hospital maintained an aquarium for leeches until the 1930s.[15] The use of leeches began to become less widespread towards the end of the 19th century.[5]

Current

Medicinal leech therapy (also referred to as Hirudotherapy or Hirudin therapy) made an international comeback in the 1970s in microsurgery,[16][17][18] used to stimulate circulation in tissues threatened by postoperative venous congestion,[16][19] particularly in finger reattachment and reconstructive surgery of the ear, nose, lip, and eyelid.[17][20] Other clinical applications of medicinal leech therapy include varicose veins, muscle cramps, thrombophlebitis, and osteoarthritis, among many varied conditions.[21] The therapeutic effect is not from the small amount of blood taken in the meal, but from the continued and steady bleeding from the wound left after the leech has detached, as well as the anesthetizing, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilating properties of the secreted leech saliva.[5] The most common complication from leech treatment is prolonged bleeding, which can easily be treated, but more serious allergic reactions and bacterial infections may also occur.[5] Leech therapy was classified by the US Food and Drug Administration as a medical device in 2004.[22]

Because of the minuscule amounts of hirudin present in leeches, it is impractical to harvest the substance for widespread medical use. Hirudin (and related substances) are synthesized using recombinant techniques. Devices called "mechanical leeches" that dispense heparin and perform the same function as medicinal leeches have been developed, but they are not yet commercially available.[23][24][25]

See also

- Helminthic therapy – other medical use of parasites

- Ichthyotherapy – medical use of fish

References

- . Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b "The CITES Appendices". cites.org. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ ISSN 1860-0743.

- PMID 2890494.

- ^ S2CID 27891377.

- PMID 3209972.

- S2CID 255377852.

- S2CID 22828659.

- ^ "Biology". Sangues Medicinales. Ricarimpex. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ]

- ^ "History". Arizona Leech Therapy. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ S2CID 195871696.

- ^ a b "网刊加载中。。。". www.tmrjournals.com. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- S2CID 247833657.

- ^ Brockbank W (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. p. 73.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-13-161891-7. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Altman LK (February 17, 1981). "The doctor's world; leeches still have their medical uses". The New York Times. p. 2.

- PMID 24653746.

- S2CID 28256939.

- S2CID 34041779.

- ^ "Applications in General Medicine". Sangues Medicinales. Ricarimpex. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "Product Classification: Leeches, Medicinal". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Salleh A (14 December 2001). "A mechanical medicinal leech?". ABC Science Online. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ^ Crystal C (14 December 2000). "Biomedical Engineering Student Invents Mechanical Leech". University of Virginia News. Archived from the original on 2001-04-14. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- University of Wisconsin, Madison, Division of Otolaryngology. Archived from the originalon December 11, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

External links

Media related to Hirudo medicinalis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hirudo medicinalis at Wikimedia Commons- Early Practices: A Brief History of Bloodletting